Wikipedia:Sandbox: Difference between revisions

m →Subpage: test edit 1 |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit Disambiguation links added |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

* Welcome to the sandbox! * |

* Welcome to the sandbox! * |

||

* Please leave this part alone * |

* Please leave this part alone * |

||

* The page is cleared regularly * |

|||

* Feel free to try your editing skills below * |

|||

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■-->{{Please leave this line alone (sandbox heading)}}<!-- |

|||

* Welcome to the sandbox! * |

|||

* Please lWikipedia |

|||

Privacy policy Terms of UseDesktopeave this part alone * |

|||

* The page is cleared regularly * |

* The page is cleared regularly * |

||

* Feel free to try your editing skills below * |

* Feel free to try your editing skills below * |

||

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■--> |

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■--> |

||

{{Short description|American actress}} |

|||

== [[Wikipedia:Sandbox/Subpage|Subpage]] == |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

Foo. |

|||

| name = Shari Eubank (teacher) |

|||

| image = <!-- just the filename, without the File: or Image: prefix or enclosing [[brackets]] --> |

|||

| alt = |

|||

| caption = |

|||

| birth_name = Shari Eubank |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|1947|06|12}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Albuquerque, New Mexico]], U.S.<br /> |

|||

| death_date = <!-- {{Death date and age |YYYY|MM|DD|YYYY|MM|DD}} or {{Death-date and age|Month DD, YYYY|Month DD, YYYY}} (death date then birth date) --> |

|||

| death_place = |

|||

| nationality = American |

|||

| other_names = |

|||

| yearsactive = 1975–1976 |

|||

| occupation = Actress |

|||

| known_for = [[Supervixens]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Shari Eubank''' (born June 12, 1947) is a retired American actress, best known for her starring role in the [[Russ Meyer]] film ''[[Supervixens]]''.<ref name="McDonough2006">{{cite book |last=McDonough |first=Jimmy |authorlink=Jimmy McDonough |title=Big Bosoms and Square Jaws: The Biography of Russ Meyer, King of the Sex Film |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iJoQi-OXBM4C&pg=PA294|year=2006 |publisher=[[Three Rivers Press]] |isbn=978-0307338440|pages=294–295}}</ref> |

|||

== [[/Subpage/]] == |

|||

Bar |

|||

[[User:Sheikbaba36524|Sheikbaba36524]] ([[User talk:Sheikbaba36524|talk]]) 06:54, 18 February 2024 (UTC) |

|||

{{Short description|Intense physical sensation of sexual release}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2018}} |

|||

[[File:Vixen poster 01.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|''[[Vixen!]]'' (1968) by directed by [[Russ Meyer]] and starring [[Erica Gavin]].]] |

|||

'''Orgasm''' (from [[Greek language|Greek]] {{lang|el|ὀργασμός}}, {{transliteration|el|orgasmos}}; "excitement, swelling") or '''sexual climax''' (or simply '''climax''') is the sudden discharge of accumulated sexual excitement during the [[Human sexual response cycle|sexual response cycle]], resulting in rhythmic, involuntary [[Muscle contraction|muscular contractions]] in the [[human pelvis|pelvic]] region characterized by sexual pleasure.<ref name=dictbiopsych>{{cite book |last1 = Winn |first1 = Philip |title = Dictionary of Biological Psychology |date = 2003 |publisher = Routledge |isbn = 9781134778157 |page = 1189 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=OEMSWCeeSPYC&pg=PA1189 |language = en |access-date = November 15, 2019 |archive-date = February 27, 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230227065023/https://books.google.com/books?id=OEMSWCeeSPYC&pg=PA1189 |url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="Rosenthal">See [https://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT153 133–135] {{webarchive|url=http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20160402152531/https://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT153 |date=April 2, 2016 }} for orgasm information, and [https://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT96 page 76] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230227065024/https://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT96 |date=February 27, 2023 }} for G-spot and vaginal nerve ending information. {{cite book |first = Martha |last = Rosenthal |title = Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society |publisher = [[Cengage]] |date = 2012 |isbn = 978-0618755714 }}</ref> Experienced by males and females, orgasms are controlled by the involuntary or [[autonomic nervous system]]. They are usually associated with involuntary actions, including muscular [[spasm]]s in multiple areas of the body, a general [[euphoria|euphoric]] sensation, and, frequently, body movements and vocalizations.<ref name="Rosenthal" /> The period after orgasm (known as the [[refractory period (sex)|resolution]] phase) is typically a relaxing experience, attributed to the release of the [[neurohormone]]s [[oxytocin]] and [[prolactin]] as well as [[endorphins]] (or "endogenous [[morphine]]").<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors = Exton MS, Krüger TH, Koch M |title = Coitus-induced orgasm stimulates prolactin secretion in healthy subjects |journal = Psychoneuroendocrinology |volume = 26 |issue = 3 |pages = 287–94 |date = April 2001 |pmid = 11166491 |doi = 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00053-6 |s2cid = 21416299 |display-authors = etal }}</ref> |

|||

Human orgasms usually result from physical [[sexual stimulation]] of the [[Human penis|penis]] in males (typically accompanied by [[ejaculation]]) and of the [[clitoris]] in females.<ref name="Rosenthal" /><ref name="Weiten">{{cite book |title = Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century |isbn = 978-1-111-18663-0 |publisher = Cengage |date = 2011 |page = 386 |access-date = January 5, 2012 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=CGu96TeAZo0C&pg=PT423 |author1 = Wayne Weiten |author2 = Dana S. Dunn |author3 = Elizabeth Yost Hammer |archive-date = February 26, 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230226053001/https://books.google.com/books?id=CGu96TeAZo0C&pg=PT423 |url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="O'Connell">{{br}}{{bull}}{{Cite journal |vauthors = O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM |title = Anatomy of the clitoris |journal = The Journal of Urology |volume = 174 |issue = 4 Pt 1 |pages = 1189–95 |date = October 2005 |pmid = 16145367 |doi = 10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd |s2cid = 26109805 }}{{br}}{{bull}}{{cite news |author = Sharon Mascall |date = June 11, 2006 |title = Time for rethink on the clitoris |work = [[BBC News]] |url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/5013866.stm |access-date = October 31, 2009 |archive-date = September 9, 2019 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190909192820/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/5013866.stm |url-status = live }}</ref> Sexual stimulation can be by self-practice ([[masturbation]]) or with a [[sex partner]] ([[Sexual penetration|penetrative sex]], [[non-penetrative sex]], or other [[Human sexual activity|sexual activity]]). It is not requisite though as possibilities exist to reach orgasm without physical stimulation through psychological means.<ref>{{Cite web|url= https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9023237/ |title=A Case Of Female Orgasm Without Genital Stimulation - PMC|website=[[National Library of Medicine]]|date=24 February 2022|accessdate=3 February 2023}}</ref> |

|||

The health effects surrounding the human orgasm are diverse. There are many physiological responses during sexual activity, including a relaxed state created by prolactin, as well as changes in the [[central nervous system]] such as a temporary decrease in the [[Metabolism|metabolic]] activity of large parts of the [[cerebral cortex]] while there is no change or increased metabolic activity in the [[Limbic system|limbic]] (i.e., "bordering") areas of the brain.<ref name="Georgiadis">{{Cite journal |vauthors = Georgiadis JR, Reinders AA, Paans AM, Renken R, Kortekaas R |title = Men versus women on sexual brain function: prominent differences during tactile genital stimulation, but not during orgasm |journal = Human Brain Mapping |volume = 30 |issue = 10 |pages = 3089–101 |date = October 2009 |pmid = 19219848 |doi = 10.1002/hbm.20733 |pmc = 6871190 }}</ref> There are also a wide range of [[sexual dysfunction]]s, such as [[anorgasmia]]. These effects affect cultural views of orgasm, such as the beliefs that orgasm and the frequency or consistency of it are either important or irrelevant for satisfaction in a sexual relationship,<ref name="Kinsey Institute">{{cite web |title = Frequently Asked Sexuality Questions to the Kinsey Institute: Orgasm |publisher = iub.edu/~kinsey/resources |access-date = January 3, 2012 |url = http://www.iub.edu/~kinsey/resources/FAQ.html#orgasm |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120105131500/http://iub.edu/~kinsey/resources/FAQ.html#orgasm |archive-date = January 5, 2012 }}</ref> and theories about the biological and evolutionary functions of orgasm.<ref name="Geoffrey Miller">{{cite book |author = Geoffrey Miller |title = The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature |publisher = [[Random House|Random House Digital]] |date = 2011 |pages = 238–239 |access-date = August 27, 2012 |isbn = 978-0307813749 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=QG-8PbZb4csC&q=The+human+clitoris+shows+no+apparent+signs+of+having+evolved+directly+through+male+mate+choice.&pg=PA238 |author-link = Geoffrey Miller (psychologist) |archive-date = February 27, 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230227065036/https://books.google.com/books?id=QG-8PbZb4csC&q=The+human+clitoris+shows+no+apparent+signs+of+having+evolved+directly+through+male+mate+choice.&pg=PA238 |url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="Wallen K, Lloyd EA">{{cite journal |title = Female sexual arousal: genital anatomy and orgasm in intercourse |journal = Hormones and Behavior |date = May 2011 |pmid = 21195073 |pmc = 3894744 |doi = 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.12.004 |volume = 59 |issue = 5 |pages = 780–92 |author = Wallen K, Lloyd EA. |last2 = Lloyd |url = https://philpapers.org/rec/WALFSA-2 |access-date = August 31, 2018 |archive-date = November 5, 2021 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211105043848/https://philpapers.org/rec/WALFSA-2 |url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

{{Short description|none}} |

|||

[[File:Portrait of Pope Paul III Farnese (by Titian) - National Museum of Capodimonte.jpg|thumb|Pope [[Pope Paul III|Paul III Farnese]] had 4 illegitimate children and made his illegitimate son [[Pier Luigi Farnese]] the first [[duke of Parma]].]] |

|||

This is a '''list of sexually active popes''', [[Catholic Church|Catholic]] [[Priesthood in the Catholic Church|priests]] who were not celibate before they became pope, and those who were legally married before becoming pope. Some candidates were allegedly [[human sexual behavior|sexually active]] before their election as [[pope]], and others were accused of being sexually active during their papacies. A number of them had offspring. |

|||

There are various classifications for those who were sexually active during their lives. Allegations of sexual activities are of varying levels of reliability, with several having been made by political opponents and being contested by modern historians. |

|||

[[File:StationaryStatesAnimation.gif|300px|thumb|right|Each of these three rows is a wave function which satisfies the time-dependent Schrödinger equation for a [[quantum harmonic oscillator|harmonic oscillator]]. Left: The real part (blue) and imaginary part (red) of the wave function. Right: The [[probability distribution]] of finding the particle with this wave function at a given position. The top two rows are examples of '''[[stationary state]]s''', which correspond to [[standing wave]]s. The bottom row is an example of a state which is ''not'' a stationary state. The right column illustrates why stationary states are called "stationary".]] |

|||

The term "Schrödinger equation" can refer to both the general equation, or the specific nonrelativistic version. The general equation is indeed quite general, used throughout quantum mechanics, for everything from the [[Dirac equation]] to [[quantum field theory]], by plugging in diverse expressions for the Hamiltonian. The specific nonrelativistic version is an approximation that yields accurate results in many situations, but only to a certain extent (see [[relativistic quantum mechanics]] and [[relativistic quantum field theory]]). |

|||

To apply the Schrödinger equation, write down the [[Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics)|Hamiltonian]] for the system, accounting for the [[Kinetic energy|kinetic]] and [[Potential energy|potential]] energies of the particles constituting the system, then insert it into the Schrödinger equation. The resulting partial [[differential equation]] is solved for the wave function, which contains information about the system. In practice, the square of the absolute value of the wave function at each point is taken to define a [[probability density function]].<ref name="Zwiebach2022"/>{{rp|78}} For example, given a wave function in position space <math>\Psi(x,t)</math> as above, we have |

|||

<math display="block">\Pr(x,t) = |\Psi(x,t)|^2.</math> |

|||

{{Please leave this line alone (sandbox heading)}}<!-- |

|||

* Welcome to the sandbox! * |

|||

* Please leave this part alone * |

|||

* The page is cleared regularly * |

|||

* Feel free to try your editing skills below * |

|||

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■--> |

|||

{{Short description|Atlantic tropical depression in 1992}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=September 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox weather event |

|||

| name = Tropical Depression One |

|||

| image = Tropical Depression One 25 june 1992 1329Z.jpg |

|||

| caption = Tropical Depression in the eastern [[Gulf of Mexico]] |

|||

| formed = June 25, 1992 |

|||

| dissipated = June 26, 1992 |

|||

}}{{Infobox weather event/NWS |

|||

| winds = 30 |

|||

| pressure = 1007 |

|||

}}{{Infobox weather event/Effects |

|||

| year = 1992 |

|||

| fatalities = 4 direct, 1 indirect, 1 missing |

|||

| damage = 2600000 |

|||

| areas = [[Cuba]], [[Florida]] |

|||

| refs = |

|||

}}{{Infobox weather event/Footer |

|||

| season = [[1992 Atlantic hurricane season]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Tropical Depression One''' was a tropical depression that in June 1992, produced [[100-year flood]]s in portions of southwestern [[Florida]]. The first tropical depression and second [[tropical cyclone]] of the [[1992 Atlantic hurricane season]], the depression developed on June 25 from a [[tropical wave]]. Located in an environment of strong [[wind shear]], much of the [[convection]] in the system was located well to the southeast of the poorly defined center of circulation. The depression moved northeastward and made [[Landfall (meteorology)|landfall]] near [[Tampa, Florida]] on June 26 shortly before dissipating over land. |

|||

The depression, in combination with an upper-level [[trough (meteorology)|trough]] to its west, produced heavy rainfall to the east of its path, peaking at {{convert|33.43|inch}} in [[Cuba]] and {{convert|25|inch}} in Florida. In Cuba, the rainfall destroyed hundreds of homes and caused two fatalities. In Florida, particularly in [[Sarasota County, Florida|Sarasota]] and [[Manatee County, Florida|Manatee]] counties, the rainfall caused severe flooding. 4,000 houses were affected, forcing thousands to evacuate. The flooding killed two in the state and was indirectly responsible for a traffic casualty. Damage in Florida totaled over $2.6 million (1992 USD, $4 million 2009 USD). |

|||

{{Short description|British single-seat WWII fighter aircraft}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Spitfire}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2016}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=February 2018}} |

|||

{|{{Infobox aircraft begin |

|||

|name= Spitfire |

|||

|image= File:Spitfire - Season Premiere Airshow 2018 (cropped).jpg |

|||

|caption= Spitfire LF Mk IX, ''MH434'' in 2018 in the markings of its original unit [[No. 222 Squadron RAF]]. |

|||

}}{{Infobox aircraft type |

|||

|type= [[Fighter aircraft|Fighter]] / [[Interceptor aircraft|Interceptor]] aircraft |

|||

|national origin= United Kingdom |

|||

|manufacturer= [[Supermarine]] |

|||

|designer= [[R. J. Mitchell]] |

|||

|first flight= 5 March 1936<ref name="Ethell p. 12" /> |

|||

|introduction= 4 August 1938<ref name="Ethell p. 12" /> |

|||

|retired= 1961 ([[Irish Air Corps]])<ref>[http://www.aeroflight.co.uk/waf/ireland/af/irl-af-all-time.htm "Ireland Air Force"]; {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101201103000/http://www.aeroflight.co.uk/waf/ireland/af/irl-af-all-time.htm |date=1 December 2010 }}. aeroflight.co. Retrieved 27 September 2009.</ref> |

|||

|status= |

|||

|primary user= [[Royal Air Force]]<!-- List only one user; for military aircraft, this is a nation or a service arm. Please DON'T add flag templates, as they limit horizontal space. --> |

|||

|more users= {{plain list| |

|||

* [[Royal Canadian Air Force]] |

|||

* [[Free French Air Force]] |

|||

* [[United States Army Air Forces]]}}<!-- Limited to THREE (3) "more users" here (4 total users). --> |

|||

|produced= 1938–1948 |

|||

|number built= 20,351<ref name="Ethell p. 117" /> |

|||

|variants with their own articles= [[Supermarine Seafire]] |

|||

|developed into= [[Supermarine Spiteful]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|} |

|||

[[File:Spitfire fly past at RAF Halton.ogg|thumb|Audio recording of Spitfire fly-past at the 2011 family day at [[RAF Halton]], Buckinghamshire]] |

|||

The '''Supermarine Spitfire''' is a British single-seat [[fighter aircraft]] used by the [[Royal Air Force]] and other [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] countries before, during, and after [[World War II]]. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griffon-engined Mk 24 using several wing configurations and guns. It was the only British fighter produced continuously throughout the war. The Spitfire remains popular among enthusiasts; around [[List of surviving Supermarine Spitfires|70 remain airworthy]], and many more are static exhibits in aviation museums throughout the world. |

|||

The Spitfire was designed as a short-range, high-performance [[interceptor aircraft]] by [[R. J. Mitchell]], chief designer at [[Supermarine]] Aviation Works, which operated as a subsidiary of [[Vickers-Armstrong]] from 1928. Mitchell developed the Spitfire's distinctive [[elliptical wing]] (designed by [[Beverley Shenstone]]) with innovative sunken rivets to have the thinnest possible cross-section, achieving a potential top speed greater than that of several contemporary fighter aircraft, including the [[Hawker Hurricane]]. Mitchell continued to refine the design until his death in 1937, whereupon his colleague [[Joseph Smith (aircraft designer)|Joseph Smith]] took over as chief designer, overseeing the Spitfire's development through [[Supermarine Spitfire variants: specifications, performance and armament|many variants]]. |

|||

During the [[Battle of Britain]] (July–October 1940), the public perceived the Spitfire to be the main RAF fighter; however, the more numerous Hurricane shouldered more of the burden of resisting the [[Luftwaffe]]. Nevertheless, the Spitfire was generally a better fighter aircraft than the Hurricane. Spitfire units had a lower attrition rate and a higher victory-to-loss ratio than Hurricanes, most likely due to the Spitfire's higher performance. During the battle, Spitfires generally engaged Luftwaffe fighters—mainly [[Messerschmitt Bf 109 variants#Bf 109E|Messerschmitt Bf 109E]]–series aircraft, which were a close match for them. |

|||

After the Battle of Britain, the Spitfire superseded the Hurricane as the principal aircraft of [[RAF Fighter Command]], and it was used in the [[European Theatre of World War II|European]], [[Mediterranean, Middle East and African theatres of World War II|Mediterranean]], [[Asiatic-Pacific Theater|Pacific]], and [[South-East Asian theatre of World War II|South-East Asian]] theatres. Much loved by its pilots, the Spitfire operated in several roles, including interceptor, photo-reconnaissance, fighter-bomber, and trainer, and it continued to do so until the 1950s. The [[Supermarine Seafire|Seafire]] was an aircraft carrier–based adaptation of the Spitfire, used in the [[Fleet Air Arm]] from 1942 until the mid-1950s. The original [[airframe]] was designed to be powered by a [[Rolls-Royce Merlin]] engine producing 1,030 [[horsepower|hp]] (768 kW). It was strong enough and adaptable enough to use increasingly powerful Merlins, and in later marks, [[Rolls-Royce Griffon]] engines producing up to 2,340 hp (1,745 kW). As a result, the Spitfire's performance and capabilities improved over the course of its service life. |

|||

In the literary traditions of the [[Upanishads]], [[Brahma Sutras]] and the [[Bhagavad Gita]], conscience is the label given to attributes composing knowledge about good and evil, that a [[Soul (spirit)|soul]] acquires from the completion of acts and consequent accretion of [[karma]] over many lifetimes.<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations''. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 382</ref> According to [[Adi Shankara]] in his ''[[Vivekachudamani]]'' morally right action (characterised as humbly and compassionately performing the primary duty of good to others without expectation of material or spiritual reward), helps "purify the heart" and provide mental tranquility but it alone does not give us "direct perception of the Reality".<ref>Shankara. ''Crest-Jewel of Discrimination'' (''[[Vivekachudamani|Veka-Chudamani]]'') (trans Prabhavananda S and Isherwood C). Vedanta Press, Hollywood. 1978. pp. 34–36, 136–37.</ref> This knowledge requires discrimination between the eternal and non-eternal and eventually a realization in [[contemplation]] that the true self merges in a universe of pure consciousness.<ref>Shankara. ''Crest-Jewel of Discrimination'' (''[[Vivekachudamani|Veka-Chudamani]]'') (trans Prabhavananda S and Isherwood C). Vedanta Press, Hollywood. 1978. p. 119.</ref> |

|||

In the [[Zoroastrian]] faith, after death a soul must face judgment at the ''Bridge of the Separator''; there, [[evil]] people are tormented by prior denial of their own higher nature, or conscience, and "to all time will they be guests for the ''House of the Lie''."<ref>John B Noss. ''Man's Religions''. Macmillan. New York. 1968. p. 477.</ref> The [[China|Chinese]] concept of [[Ren (Confucianism)|Ren]], indicates that conscience, along with social etiquette and correct relationships, assist humans to follow ''The Way'' ([[Tao]]) a mode of life reflecting the implicit human capacity for goodness and harmony.<ref>AS Cua. ''Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics''. Catholic University of America Press. Washington. 1998.</ref> |

|||

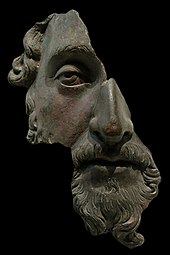

[[File:Bronze Marcus Aurelius Louvre.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Marcus Aurelius]] bronze fragment, Louvre, Paris: "To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness."]] |

|||

Conscience also features prominently in [[Buddhism]].<ref>Jayne Hoose (ed) ''Conscience in World Religions''. University of Notre Dame Press. 1990.</ref> In the [[Pali]] scriptures, for example, [[Buddha]] links the positive aspect of ''conscience'' to a pure heart and a calm, well-directed mind. It is regarded as a spiritual power, and one of the "Guardians of the World". The Buddha also associated conscience with compassion for those who must endure cravings and suffering in the world until right conduct culminates in right mindfulness and right [[contemplation]].<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The Religious Experience of Mankind''. Fontana. 1971 p. 118.</ref> [[Santideva]] (685–763 CE) wrote in the [[Bodhicaryavatara]] (which he composed and delivered in the great northern Indian Buddhist university of [[Nalanda]]) of the spiritual importance of perfecting virtues such as [[generosity]], [[forbearance]] and training the awareness to be like a "block of wood" when attracted by vices such as [[pride]] or [[lust]]; so one can continue advancing towards right understanding in meditative absorption.<ref>Santideva. ''The Bodhicaryavatara''. trans Crosby K and Skilton A. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1995. pp. 38, 98</ref> ''Conscience'' thus manifests in Buddhism as unselfish love for all living beings which gradually intensifies and awakens to a purer awareness<ref>Lama Anagarika Govinda in Jeffery Paine (ed) ''Adventures with the Buddha: A Buddhism Reader''. WW Norton. London. pp. 92–93.</ref> where the mind withdraws from sensory interests and becomes aware of itself as a single whole.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Steps Along the Path |url=https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/thai/thate/stepsalong.html |access-date=2022-12-13 |website=www.accesstoinsight.org}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Roman Emperor]] [[Marcus Aurelius]] wrote in his ''[[Meditations]]'' that conscience was the human capacity to live by rational principles that were congruent with the true, tranquil and harmonious nature of our mind and thereby that of the Universe: "To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness ... the only rewards of our existence here are an unstained character and unselfish acts."<ref>Marcus Aurelius. ''Meditations''. Gregory Hays (trans). Weidenfeld and & Nicolson. London. 2003 pp. 70, 75.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Munqidh min al-dalal (last page).jpg|thumb|upright|Last page of [[Al-Ghazali|Ghazali]]'s autobiography in MS Istanbul, Shehid Ali Pasha 1712, dated [[Anno Hegirae|A.H.]] 509 = 1115–1116. Ghazali's crisis of epistemological skepticism was resolved by "a light which God Most High cast into my breast ... the key to most knowledge."]] |

|||

The [[Islamic]] concept of ''[[Taqwa]]'' is closely related to conscience. In the [[Qur’ān]] verses 2:197 & 22:37 Taqwa refers to "right conduct" or "[[piety]]", "guarding of oneself" or "guarding against evil".<ref>Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick. ''The Vision of Islam''. I. B. Tauris. 2000. {{ISBN|1-86064-022-2}} pp. 282–85</ref> [[Qur’ān]] verse 47:17 says that God is the ultimate source of the believer's taqwā which is not simply the product of individual will but requires inspiration from God.<ref>Ames Ambros and Stephan Procházka. ''A Concise Dictionary of Koranic Arabic''. Reichert Verlag 2004. {{ISBN|3-89500-400-6}} p. 294.</ref> In [[Qur’ān]] verses 91:7–8, God the Almighty talks about how He has perfected the soul, the conscience and has taught it the wrong (fujūr) and right (taqwā). Hence, the awareness of vice and virtue is inherent in the soul, allowing it to be tested fairly in the life of this world and tried, held accountable on the day of judgment for responsibilities to God and all humans.<ref>Azim Nanji. 'Islamic Ethics' in Singer P (ed). ''A Companion to Ethics''. Blackwell, Oxford 1995. p. 108.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Sura49.pdf|left|thumb|upright|[[Qur’ān]] Sura 49. Surah al-Hujurat, 49:13 declares: "come to know each other, the noblest of you, in the sight of God, are the ones possessing taqwá".]] |

|||

[[Qur’ān]] verse 49:13 states: "O humankind! We have created you out of male and female and constituted you into different groups and societies, so that you may come to know each other-the noblest of you, in the sight of God, are the ones possessing taqwā." In [[Islam]], according to eminent theologians such as [[Al-Ghazali]], although events are ordained (and written by God in al-Lawh al-Mahfūz, the ''Preserved Tablet''), humans possess free will to choose between wrong and right, and are thus responsible for their actions; the conscience being a dynamic personal connection to God enhanced by knowledge and practise of the [[Five Pillars of Islam]], deeds of piety, repentance, self-discipline and prayer; and disintegrated and metaphorically covered in blackness through sinful acts.<ref>John B Noss. ''Man's Religions''. The Macmillan Company, New York. 1968 Ch. 16 pp. 758–59</ref> [[Marshall Hodgson]] wrote the three-volume work: ''The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization''.<ref>Marshall G. S. Hodgson. ''The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam''. University of Chicago Press. 1975 {{ISBN|978-0-226-34686-1}}. Winner of [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]] Prize.</ref> |

|||

[[File:William Holman Hunt - The Awakening Conscience - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|upright|[[The Awakening Conscience]], [[William Holman Hunt|Holman Hunt]], 1853]] |

|||

In the Protestant Christian tradition, [[Martin Luther]] insisted in the [[Diet of Worms]] that his conscience was captive to the Word of God, and it was neither safe nor right to go against conscience. To Luther, conscience falls within the ethical, rather than the religious, sphere.<ref name=Tillich>{{cite book|last1=Tillich|first1=Paul|title=Morality and Beyond|url=https://archive.org/details/moralitybeyond00till|url-access=registration|date=1963|publisher=Harper & Row, Publishers|location=New York|page=[https://archive.org/details/moralitybeyond00till/page/69 69]}}</ref> [[John Calvin]] saw conscience as a battleground: "the enemies who rise up in our conscience against his Kingdom and hinder his decrees prove that God's throne is not firmly established therein".<ref>Calvin, ''Institutes of the Christian religion'', Book 2, chapter 8, quoted in:{{cite book |last= Wogaman |first= J. Pilip |author-link= J. Philip Wogaman |title= Christian ethics: a historical introduction |year= 1993 |publisher= Westminster/John Knox Press |location= Louisville, Kentucky |isbn= 978-0-664-25163-5 |pages= [https://archive.org/details/christianethicsh0000woga/page/119 119, 340] |quote=the enemies who rise up in our conscience against his Kingdom and hinder his decrees prove that God's throne is not firmly established therein. |url= https://archive.org/details/christianethicsh0000woga/page/119 }}</ref> Many [[Christians]] regard following one's conscience as important as, or even more important than, obeying human [[authority]].<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations''. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 376</ref> According to the bible, written in Romans 2:15, conscience is the one bearing witness, accusing or excusing one another, so we would know when we break the law written in our hearts; the guilt we feel when we do something wrong tells us that we need to repent."<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations''. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 364</ref> This can sometimes (as with the conflict between [[William Tyndale]] and [[Thomas More]] over the translation of the Bible into English) lead to moral quandaries: "Do I unreservedly obey my Church/priest/military/political leader or do I follow my own inner feeling of right and wrong as instructed by prayer and a personal reading of scripture?"<ref>Brian Moynahan. ''William Tyndale: If God Spare My Life''. Abacus. London. 2003 pp. 249–50</ref> Some contemporary Christian churches and religious groups hold the moral teachings of the [[Ten Commandments]] or of [[Jesus]] as the highest authority in any situation, regardless of the extent to which it involves responsibilities in law.<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The World's Religions: Old Traditions and Modern Transformations''. Cambridge University Press. 1989. p. 353</ref> In the [[Gospel of John]] (7:53–8:11) (King James Version) Jesus challenges those accusing a woman of adultery stating: "'He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.' And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground. And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one" [However the word 'conscience' is not in the original New Testament Greek, and is not in the vast majority of Bible versions.] (see [[Jesus and the woman taken in adultery]]). In the [[Gospel of Luke]] (10: 25–37) Jesus tells the story of how a despised and heretical [[Samaritan]] (see [[Parable of the Good Samaritan]]) who (out of compassion/pity - the word 'conscience' is not used) helps an injured stranger beside a road, qualifies better for eternal life by loving his neighbor, than a priest who passes by on the other side.<ref>Guthrie D, Motyer JA, Stibbs AM, Wiseman DLJ (eds). ''New Bible Commentary'' 3rd ed. Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester. 1989. p. 905.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Lytras nikiforos antigone polynices.jpeg|left|thumb|[[Nikiforos Lytras]], ''Antigone in front of the dead Polynices'' (1865), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Greece-Alexandros Soutzos Museum.]] |

|||

This dilemma of obedience in conscience to divine or state law, was demonstrated dramatically in [[Antigone]]'s defiance of [[Creon of Thebes|King Creon]]'s order against burying her brother an alleged traitor, appealing to the "[[natural law|unwritten law]]" and to a "longer allegiance to the dead than to the living".<ref>Robert Graves. ''The Greek Myths: 2'' (London: Penguin, 1960). p. 380</ref> |

|||

{{anchor|ConscienceInCatholicTheology}}[[Catholic]] [[theology]] sees conscience as the last practical "judgment of reason which at the appropriate moment enjoins [a person] to do good and to avoid evil".<ref>{{anchor|CCC}}''[[Catechism of the Catholic Church]]'' – English translation (U.S., 2nd edition) (English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica, copyright 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana) (Glossary and Index Analyticus, copyright 2000, U.S. Catholic Conference, Inc.). {{ISBN|1-57455-110-8}} paragraph 1778</ref> The [[Second Vatican Council]] (1962–65) describes: "Deep within his conscience man discovers a law which he has not laid upon himself but which he must obey. Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, tells him inwardly at the right movement: do this, shun that. For man has in his heart a law inscribed by God. His dignity lies in observing this law, and by it he will be judged. His conscience is man’s most secret core, and his sanctuary. There he is alone with God whose voice echoes in his depths."<ref>Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press 1992. ''Gaudium and Spes'' 16. Cfr. Joseph Ratzinger, ''On Conscience'', San Francisco: Ignatius Press 2007</ref> Thus, conscience is not like the will, nor a habit like prudence, but "the interior space in which we can listen to and hear the truth, the good, the voice of God. It is the inner place of our relationship with Him, who speaks to our heart and helps us to discern, to understand the path we ought to take, and once the decision is made, to move forward, to remain faithful"<ref>{{Cite web |title=Whispers in the Loggia: "Jesus Always Invites Us. He Does Not Impose." |url=http://whispersintheloggia.blogspot.com/2013/06/jesus-always-invites-us-he-does-not.html |access-date=2022-12-13 |language=en}}</ref> In terms of logic, conscience can be viewed as the practical conclusion of a moral syllogism whose major premise is an objective norm and whose minor premise is a particular case or situation to which the norm is applied. Thus, Catholics are taught to carefully educate themselves as to revealed norms and norms derived therefrom, so as to form a correct conscience. Catholics are also to examine their conscience daily and with special care before [[Confession (religion)|confession]]. Catholic teaching holds that, "Man has the right to act according to his conscience and in freedom so as personally to make moral decisions. He must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience. Nor must he be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters".<ref>''[[#CCC|Catechism of the Catholic Church]]'', paragraph 1782</ref> This right of conscience does not allow one to arbitrarily disagree with Church teaching and claim that one is acting in accordance with conscience. A sincere conscience presumes one is diligently seeking moral truth from authentic sources, that is, seeking to conform oneself to that moral truth by listening to the authority established by Christ to teach it. Nevertheless, despite one's best effort, "[i]t can happen that moral conscience remains in ignorance and makes erroneous judgments about acts to be performed or already committed ... This ignorance can often be imputed to personal responsibility ... In such cases, the person is culpable for the [[evil|wrong]] he commits."<ref>''[[#CCC|Catechism of the Catholic Church]]'', paragraph 1790–91</ref> {{Citation needed span|text=Thus, if one realizes one may have made a mistaken judgment, one's conscience is said to be vincibly erroneous and it is not a valid norm for action. One must first remove the source of error and do one's best to achieve a correct judgment. If, however, one is not aware of one's error or if, despite an honest and diligent effort one cannot remove the error by study or seeking advice, then one's conscience may be said to be invincibly erroneous. It binds since one has subjective certainty that one is correct. The act resulting from acting on the invincibly erroneous conscience is not good in itself, yet this deformed act or material sin against God's right order and the objective norm is not imputed to the person. The formal obedience given to such a judgment of conscience is good. Some Catholics appeal to conscience in order to justify dissent, not on the level of conscience properly understood, but on the level of the principles and norms which are supposed to inform conscience. For example, some priests make on the use of the so-called [[Internal and external forum (Catholic canon law)#"Internal forum solution"|internal forum solution]] (which is not sanctioned by the [[Magisterium]]) to justify actions or lifestyles incompatible with Church teaching, such as Christ's prohibition of remarriage after divorce or sexual activity outside marriage.|date=March 2021}} The [[Catholic Church]] has warned that "rejection of the Church's authority and her teaching ... can be at the source of errors in judgment in [[moral]] conduct".<ref>''[[#CCC|Catechism of the Catholic Church]]'', paragraph 1792</ref> An example of someone following his conscience to the point of accepting the consequence of being condemned to death is Sir [[Thomas More]] (1478-1535).<ref>Samuel Willard Crompton, "Thomas More: And His Struggles of Conscience" (Chelsea House Publications, 2006); Marc D. Guerra, 'Thomas More's Correspondence on Conscience', in: ''Religion & Liberty'' 10(2010)6 <https://acton.org/thomas-mores-correspondence-conscience>; Prof. Gerald Wegemer, "Integrity and Conscience in the Life and Thought of Thomas More" [21 aug. 2006]<http://thomasmoreinstitute.org.uk/papers/integrity-and-conscience-in-the-life-and-thought-of-thomas-more/>; http://sacredheartmercy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/A-Reflection-on-Conscience.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170911120158/http://sacredheartmercy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/A-Reflection-on-Conscience.pdf |date=11 September 2017 }}</ref> A theologian who wrote on the distinction between the 'sense of duty' and the 'moral sense', as two aspects of conscience, and who saw the former as some feeling that can only be explained by a divine Lawgiver, was [[John Henry Cardinal Newman]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Newman |first=John Henry |url=http://archive.org/details/a599830700newmuoft |title=An essay in aid of a grammar of assent |date=1887 |publisher=London : Longmans, Green |others=Saint Mary's College of California}}</ref> A well known saying of him is that he would first toast on his conscience and only then on the pope, since his conscience brought him to acknowledge the authority of the pope.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Newman Reader - Letter to the Duke of Norfolk - Section 5 |url=https://www.newmanreader.org/works/anglicans/volume2/gladstone/section5.html |access-date=2022-12-13 |website=www.newmanreader.org}}</ref> |

|||

[[Judaism]] arguably does not require uncompromising obedience to religious authority; the case has been made that throughout [[Jewish history]], [[rabbis]] have circumvented laws they found unconscionable, such as capital punishment.<ref>Harold H Schulweis. ''Conscience: The Duty to Obey and the Duty to Disobey''. Jewish Lights Publishing. 2008.</ref> Similarly, although an occupation with national destiny has been central to the Jewish faith (see [[Zionism]]) many scholars (including [[Moses Mendelssohn]]) stated that conscience as a personal revelation of scriptural truth was an important adjunct to the [[Talmudic]] tradition.<ref>Ninian Smart. ''The Religious Experience of Mankind''. Collins. NY. 1969 pp. 395–400.</ref><ref>Levi Meier (Ed.) ''Conscience and Autonomy within Judaism: A Special Issue of the Journal of Psychology and Judaism''. Springer-Verlag. New York {{ISBN|978-0-89885-364-3}}.</ref> The concept of [[inner light]] in the [[Religious Society of Friends]] or [[Quaker]]s is associated with conscience.<ref name="autogenerated2000"/> [[Freemasonry]] describes itself as providing an adjunct to religion and key symbols found in a [[Freemason]] Lodge are the ''[[steel square|square]]'' and ''[[compass (drafting)|compasses]]'' explained as providing lessons that Masons should "square their actions by the square of conscience", learn to "circumscribe their desires and keep their passions within due bounds toward all mankind."<ref name="spoilt">{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Gilkes |

|||

| first = Peter |

|||

|date=July 2004 |

|||

| title = Masonic ritual: Spoilt for choice |

|||

| journal = Masonic Quarterly Magazine |

|||

| issue = 10 |

|||

| url = http://www.mqmagazine.co.uk/issue-10/p-61.php |

|||

| access-date =7 May 2007}}</ref> The historian [[Manning Clark]] viewed ''conscience'' as one of the comforters that religion placed between man and death but also a crucial part of the quest for grace encouraged by the [[Book of Job]] and the [[Book of Ecclesiastes]], leading us to be paradoxically closest to the truth when we suspect that what matters most in life ("being there when everyone suddenly understands what it has all been for") can never happen.<ref>Manning Clark. ''The Quest for Grace''. Penguin Books, Ringwood. 1991 p. 220.</ref> [[Leo Tolstoy]], after a decade studying the issue (1877–1887), held that the only power capable of resisting the evil associated with materialism and the drive for social power of religious institutions, was the capacity of humans to reach an individual spiritual truth through reason and conscience.<ref>Aylmer Maude. ''Introduction to Leo Tolstoy. On Life and Essays on Religion'' (A Maude trans) Oxford University Press. London. 1950 (repr) pxv.</ref> Many prominent [[religious]] works about conscience also have a significant philosophical component: examples are the works of [[Al-Ghazali]],<ref name="autogenerated1966">{{cite journal | last1 = Najm | first1 = Sami M. | year = 1966 | title = The Place and Function of Doubt in the Philosophies of Descartes and Al-Ghazali | journal = Philosophy East and West | volume = 16 | issue = 3–4| pages = 133–41 | doi = 10.2307/1397536 | jstor = 1397536 }}</ref> [[Avicenna]],<ref name="autogenerated67">Nader El-Bizri. "Avicenna's De Anima between Aristotle and Husserl" in Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (ed) ''The Passions of the Soul in the Metamorphosis of Becoming''. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Dordrecht 2003 pp. 67–89.</ref> [[Aquinas]],<ref name="autogenerated145">Henry Sidgwick. ''Outlines of the History of Ethics''. Macmillan. London. 1960 pp. 145, 150.</ref> [[Joseph Butler]]<ref name="autogenerated365">Rurak, James (1980). "Butler's Analogy: A Still Interesting Synthesis of Reason and Revelation", ''Anglican Theological Review'' 62 (October) pp. 365–81</ref> and [[Dietrich Bonhoeffer]]<ref name="autogenerated24">Dietrich Bonhoeffer. ''Ethics''. Eberhard Bethge (ed.) Neville Horton Smith (trans.) Collins. London 1963 p. 24</ref> (all discussed in the philosophical views section). |

|||

[[Baruch Spinoza|Benedict de Spinoza]] in his [[Ethics (Spinoza)|''Ethics'']], published after his death in 1677, argued that most people, even those that consider themselves to exercise [[free will]], make moral decisions on the basis of imperfect sensory information, inadequate understanding of their mind and will, as well as emotions which are both outcomes of their contingent physical existence and forms of thought defective from being chiefly impelled by self-preservation.<ref>Spinoza. ''Ethics''. Everyman's Library JM Dent, London. 1948. Part 2 proposition 35. Part 3 proposition 11.</ref> The solution, according to Spinoza, was to gradually increase the capacity of our reason to change the forms of thought produced by emotions and to fall in love with viewing problems requiring moral decision from the perspective of eternity.<ref>Spinoza. ''Ethics''. Everyman's Library JM Dent, London. 1948. Part 4 proposition 59, Part 5 proposition 30</ref> Thus, living a life of peaceful conscience means to Spinoza that reason is used to generate adequate ideas where the mind increasingly sees the world and its conflicts, our desires and passions ''sub specie aeternitatis'', that is without reference to time.<ref>Roger Scruton. "Spinoza" in Raphael F and Monk R (eds). ''The Great Philosophers''. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. London. 2000. p. 141.</ref> [[Hegel]]'s obscure and [[mystical]] [[Philosophy of Mind]] held that the absolute right of ''freedom of conscience'' facilitates human understanding of an all-embracing unity, an absolute which was rational, real and true.<ref>Richard L Gregory. ''The Oxford Companion to the Mind''. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1987 p. 308.</ref> Nevertheless, Hegel thought that a functioning State would always be tempted not to recognize conscience in its form of subjective knowledge, just as similar non-objective opinions are generally rejected in science.<ref>Georg Hegel. ''Philosophy of Right''. Knox TM trans, Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1942. para 137.</ref> A similar idealist notion was expressed in the writings of [[Joseph Butler]] who argued that conscience is [[God]]-given, should always be obeyed, is intuitive, and should be considered the "constitutional monarch" and the "universal moral faculty": "conscience does not only offer itself to show us the way we should walk in, but it likewise carries its own authority with it."<ref>Joseph Butler "Sermons" in ''The Works of Joseph Butler''. (Gladstone WE ed), Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1896, Vol II p. 71.</ref> Butler advanced ethical speculation by referring to a duality of regulative principles in human nature: first, "self-love" (seeking individual happiness) and second, "benevolence" (compassion and seeking good for another) in ''conscience'' (also linked to the [[agape]] of [[situational ethics]]).<ref name="autogenerated365"/> Conscience tended to be more authoritative in questions of moral judgment, thought Butler, because it was more likely to be clear and certain (whereas calculations of self-interest tended to probable and changing conclusions).<ref>Henry Sidgwick. ''Outlines of the History of Ethics''. Macmillan, London. 1960 pp. 196–97.</ref> [[John Selden]] in his ''Table Talk'' expressed the view that an awake but excessively scrupulous or ill-trained ''conscience'' could hinder resolve and practical action; it being "like a horse that is not well wayed, he starts at every bird that flies out of the hedge".<ref>John Selden. ''Table Talk''. Garnett R, Valee L and Brandl A (eds) The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology. The Grolier Society. Toronto. 1923. Vol 14. p. 67.</ref> |

|||

As the sacred texts of ancient [[Hindu]] and [[Buddhist]] philosophy became available in German translations in the 18th and 19th centuries, they influenced philosophers such as [[Schopenhauer]] to hold that in a healthy mind only deeds oppress our ''conscience'', not wishes and thoughts; "for it is only our deeds that hold us up to the mirror of our will"; the ''good conscience'', thought Schopenhauer, we experience after every disinterested deed arises from direct recognition of our own inner being in the phenomenon of another, it affords us the verification "that our true self exists not only in our own person, this particular manifestation, but in everything that lives. By this the heart feels itself enlarged, as by egotism it is contracted."<ref>Arthur Schopenhauer. ''The World as Will and Idea''. Vol 1. Routledge and Kegan Paul. London. 1948. pp. 387, 482. "I believe that the influence of the Sanskrit literature will penetrate not less deeply than did the revival of Greek literature in the 15th century." p xiii.</ref> |

|||

[[Immanuel Kant]], a central figure of the [[Age of Enlightenment]], likewise claimed that two things filled his mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and more steadily they were reflected on: "the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me ... the latter begins from my invisible self, my personality, and exhibits me in a world which has true infinity but which I recognise myself as existing in a universal and necessary (and not only, as in the first case, contingent) connection."<ref>Kant I. "The Noble Descent of Duty" in P Singer (ed). ''Ethics''. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 41.</ref> The 'universal connection' referred to here is Kant's [[categorical imperative]]: "act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."<ref>Kant I. "The Categorical Imperative" in P Singer (ed). ''Ethics''. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 274.</ref> Kant considered ''critical conscience'' to be an internal court in which our thoughts accuse or excuse one another; he acknowledged that morally mature people do often describe contentment or peace in the [[Soul (spirit)|soul]] after following conscience to perform a duty, but argued that for such acts to produce virtue their primary motivation should simply be duty, not expectation of any such bliss.<ref>Kant I. "The Doctrine of Virtue" in ''Metaphyics and Morals''. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 1991. pp. 183 and 233–34.</ref> Rousseau expressed a similar view that conscience somehow connected man to a greater [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] unity. [[John Plamenatz]] in his critical examination of [[Rousseau]]'s work considered that ''conscience'' was there defined as the feeling that urges us, in spite of contrary passions, towards two harmonies: the one within our minds and between our passions, and the other within society and between its members; "the weakest can appeal to it in the strongest, and the appeal, though often unsuccessful, is always disturbing. However, corrupted by power or wealth we may be, either as possessors of them or as victims, there is something in us serving to remind us that this corruption is against nature."<ref>John Plamenatz. ''Man and Society''. Vol 1. Longmans. London. 1963 p. 383.</ref> |

|||

[[File:JohnLocke.png|thumb|upright|[[John Locke]] viewed the widespread social fact of conscience as a justification for natural rights.]] |

|||

[[File:AdamSmith1790b.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Adam Smith]]: conscience shows what relates to ourselves in its proper shape and dimensions]] |

|||

[[File:Samuel Johnson by John Opie.jpg|left|thumb|upright|[[Samuel Johnson]] (1775) stated that "No man's conscience can tell him the right of another man."]] |

|||

Other philosophers expressed a more sceptical and pragmatic view of the operation of "conscience" in society.<ref>Hill T Jr "Four Conceptions of Conscience" in Shapiro I and Adams R. ''Integrity and Conscience''. New York University Press, New York 1998 p. 31.</ref> |

|||

[[John Locke]] in his ''Essays on the Law of Nature'' argued that the widespread fact of human conscience allowed a philosopher to infer the necessary existence of objective moral laws that occasionally might contradict those of the state.<ref>[[Roger Woolhouse]]. ''Locke: A Biography''. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 2007. p. 53.</ref> Locke highlighted the [[metaethics]] problem of whether accepting a statement like "follow your ''conscience''" supports [[subject (philosophy)|subjectivist]] or [[objectivity (philosophy)|objectivist]] conceptions of conscience as a guide in concrete morality, or as a spontaneous revelation of eternal and immutable principles to the individual: "if conscience be a proof of innate principles, contraries may be innate principles; since some men with the same bent of conscience prosecute what others avoid."<ref>John Locke. ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding''. Dover Publications. New York. 1959. {{ISBN|0-486-20530-4}}. Vol 1. ch II. pp. 71-72fn1.</ref> [[Thomas Hobbes]] likewise pragmatically noted that opinions formed on the basis of ''conscience'' with full and honest conviction, nevertheless should always be accepted with humility as potentially erroneous and not necessarily indicating absolute knowledge or truth.<ref>Thomas Hobbes. ''Leviathan'' (Molesworth W ed) J Bohn. London, 1837 Pt 2. Ch 29 p. 311.</ref> [[William Godwin]] expressed the view that ''conscience'' was a memorable consequence of the "perception by men of every creed when the descend into the scene of busy life" that they possess [[free will]].<ref>William Godwin. ''Enquiry Concerning Political Justice''. Codell Carter K (ed), Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1971 Appendix III 'Thoughts on Man' Essay XI 'Of Self Love and Benevolence' p. 338.</ref> [[Adam Smith]] considered that it was only by developing a ''critical conscience'' that we can ever see what relates to ourselves in its proper shape and dimensions; or that we can ever make any proper comparison between our own interests and those of other people.<ref>Adam Smith. ''The Theory of Moral Sentiments''. Part III, section ii, Ch III in Rogers K (ed) Self Interest: An Anthology of Philosophical Perspectives. Routledge. London. 1997 p. 151.</ref> [[John Stuart Mill]] believed that idealism about the role of ''conscience'' in government should be tempered with a practical realisation that few men in society are capable of directing their minds or purposes towards distant or unobvious interests, of disinterested regard for others, and especially for what comes after them, for the idea of posterity, of their country, or of humanity, whether grounded on sympathy or on a conscientious feeling.<ref name="Mill193-194">John Stuart Mill. "Considerations on Representative Government". Ch VI. In Rogers K (ed) ''Self Interest: An Anthology of Philosophical Perspectives''. Routledge. London. 1997 pp. 193–94</ref> Mill held that certain amount of ''conscience'', and of disinterested public spirit, may fairly be calculated on in the citizens of any community ripe for [[representative government]], but that "it would be ridiculous to expect such a degree of it, combined with such intellectual discernment, as would be proof against any plausible fallacy tending to make that which was for their class interest appear the dictate of justice and of the general good."<ref name="Mill193-194"/> |

|||

[[Josiah Royce]] (1855–1916) built on the [[transcendental idealism]] view of conscience, viewing it as the ideal of life which constitutes our moral personality, our plan of being ourself, of making common sense ethical decisions. But, he thought, this was only true insofar as our ''conscience'' also required loyalty to "a mysterious higher or deeper self".<ref>John K Roth (ed). ''The Philosophy of Josiah Royce''. Thomas Y Crowell Co. New York. 1971 pp. 302–15.</ref> |

|||

In the modern Christian tradition this approach achieved expression with [[Dietrich Bonhoeffer]] who stated during his imprisonment by the [[Nazis]] in [[World War II]] that ''conscience'' for him was more than practical reason, indeed it came from a "depth which lies beyond a man's own will and his own reason and it makes itself heard as the call of human existence to unity with itself."<ref>Dietrich Bonhoeffer. ''Ethics''. (Eberhard Bethge (ed) Neville Horton Smith (trans) Collins. London 1963 p. 242</ref> For Bonhoeffer a ''guilty conscience'' arose as an indictment of the loss of this unity and as a warning against the loss of one's self; primarily, he thought, it is directed not towards a particular kind of doing but towards a particular mode of being. It protests against a doing which imperils the unity of this being with itself.<ref name="autogenerated24"/> ''Conscience'' for Bonhoeffer did not, like shame, embrace or pass judgment on the morality of the whole of its owner's life; it reacted only to certain definite actions: "it recalls what is long past and represents this disunion as something which is already accomplished and irreparable".<ref name="Bonhoffer66">Dietrich Bonhoeffer. ''Ethics''. (Eberhard Bethge (ed) Neville Horton Smith (trans) Collins. London 1963 p. 66</ref> The man with a ''conscience'', he believed, fights a lonely battle against the "overwhelming forces of inescapable situations" which demand moral decisions despite the likelihood of adverse consequences.<ref name="Bonhoffer66"/> [[Simon Soloveychik]] has similarly claimed that the ''truth'' distributed in the world, as the statement about human [[dignity]], as the affirmation of the line between [[good and evil]], lives in people as conscience.<ref>[[Simon Soloveychik]]. ''Parenting For Everyone''. Ch 12 [http://www.parentingforeveryone.com/book2part2ch12 "A Chapter on Conscience"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070516020813/http://www.parentingforeveryone.com/book2part2ch12 |date=16 May 2007 }}. 1986. Retrieved 23 October 2009.</ref> |

|||

<div style="clear:left;float:left;"> |

|||

[[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R0211-316, Dietrich Bonhoeffer mit Schülern.jpg|thumb|left|[[Dietrich Bonhoeffer]] (1932)]] |

|||

</div> |

|||

As [[Hannah Arendt]] pointed out, however, (following the utilitarian [[John Stuart Mill]] on this point): a bad conscience does not necessarily signify a bad character; in fact only those who affirm a commitment to applying moral standards will be troubled with remorse, guilt or shame by a bad ''conscience'' and their need to regain integrity and wholeness of the self.<ref>Hannah Arendt. ''Crises of the Republic''. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. New York. 1972 p. 62.</ref><ref>John Stuart Mill. "Utilitarianism" and "On Liberty" in ''Collected Works''. University of Toronto Press. Toronto. 1969 Vols 10 and 18. Ch 3. pp. 228–29 and 263.</ref> Representing our soul or true self by analogy as our house, Arendt wrote that "conscience is the anticipation of the fellow who awaits you if and when you come home."<ref name="autogenerated191">Hannah Arendt. ''The Life of the Mind''. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1978. p. 191.</ref> Arendt believed that people who are unfamiliar with the process of silent critical reflection about what they say and do will not mind contradicting themselves by an immoral act or crime, since they can "count on its being forgotten the next moment;" bad people are not full of regrets.<ref name="autogenerated191"/> Arendt also wrote eloquently on the problem of languages distinguishing the word [[consciousness]] from ''conscience''. One reason, she held, was that ''conscience'', as we understand it in moral or legal matters, is supposedly always present within us, just like ''consciousness'': "and this conscience is also supposed to tell us what to do and what to repent; before it became the ''lumen naturale'' or [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]]'s practical reason, it was the voice of God."<ref>Hannah Arendt. ''The Life of the Mind''. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1978. p. 190.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Albert Einstein Head Cleaned N Cropped.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Albert Einstein]] associated conscience with suprapersonal thoughts, feelings and aspirations.]] |

|||

[[Albert Einstein]], as a self-professed adherent of [[humanism]] and [[rationalism]], likewise viewed an enlightened religious person as one whose ''conscience'' reflects that he "has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value."<ref>{{cite journal|last=Einstein|first=A.|year=1940|title=Science and religion |journal= [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=146 |pages=605–07|doi=10.1038/146605a0 |issue=3706 |bibcode=1940Natur.146..605E|s2cid=9421843|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Einstein often referred to the "inner voice" as a source of both moral and physical knowledge: "[[Quantum mechanics]] is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings one closer to the secrets of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice."<ref>Quoted in Gino Segre. ''Faust in Copenhagen: A Struggle for the Soul of Physics and the Birth of the Nuclear Age''. Pimlico. London 2007. p. 144.</ref> |

|||

[[Simone Weil]] who fought for the French resistance (the [[Maquis (World War II)|Maquis]]) argued in her final book ''[[The Need for Roots]]: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind'' that for society to become more just and protective of liberty, obligations should take precedence over rights in moral and political philosophy and a spiritual awakening should occur in the ''conscience'' of most citizens, so that social obligations are viewed as fundamentally having a transcendent origin and a beneficent impact on human character when fulfilled.<ref>Simone Weil. ''The Need For Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind''. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London. 1952 (repr 2003). {{ISBN|0-415-27101-0}} pp. 13 et seq.</ref><ref>Hellman, John. ''Simone Weil: An Introduction to Her Thought''. Wilfrid Laurier, University Press, Waterloo, Ontario. 1982.</ref> [[Simone Weil]] also in that work provided a psychological explanation for the mental peace associated with a ''good conscience'': "the liberty of men of goodwill, though limited in the sphere of action, is complete in that of conscience. For, having incorporated the rules into their own being, the prohibited possibilities no longer present themselves to the mind, and have not to be rejected."<ref>Simone Weil. ''The Need For Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind''. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London. 1952 (repr 2003). {{ISBN|0-415-27101-0}} p. 13.</ref> |

|||

Alternatives to such [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] and [[idealism|idealist]] opinions about conscience arose from [[philosophical realism|realist]] and [[materialism|materialist]] perspectives such as those of [[Charles Darwin]]. Darwin suggested that "any [[animal]] whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or as nearly as well developed, as in man."<ref>Charles Darwin. "The Origin of the Moral Sense" in P Singer (ed). ''Ethics''. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 44.</ref> [[Émile Durkheim]] held that the [[Soul (spirit)|soul]] and conscience were particular forms of an impersonal principle diffused in the relevant group and communicated by [[totemic]] ceremonies.<ref>Émile Durkheim. ''The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life''. The Free Press. New York. 1965 p. 299.</ref> [[AJ Ayer]] was a more recent realist who held that the existence of ''conscience'' was an empirical question to be answered by sociological research into the moral habits of a given person or group of people, and what causes them to have precisely those habits and feelings. Such an inquiry, he believed, fell wholly within the scope of the existing [[social sciences]].<ref>AJ Ayer. "Ethics for Logical Positivists" in P Singer (ed). ''Ethics''. Oxford University Press. NY 1994 p. 151.</ref> [[George Edward Moore]] bridged the idealistic and sociological views of 'critical' and 'traditional' conscience in stating that the idea of abstract 'rightness' and the various degrees of the specific emotion excited by it are what constitute, for many persons, the specifically 'moral sentiment' or ''conscience''. For others, however, an action seems to be properly termed 'internally right', merely because they have previously regarded it as right, the idea of 'rightness' being present in some way to his or her mind, but not necessarily among his or her deliberately constructed motives.<ref>GE Moore. ''Principia Ethica''. Cambridge University Press. London. 1968 pp. 178–79.</ref> |

|||

The French philosopher [[Simone de Beauvoir]] in ''A Very Easy Death'' (''Une mort très douce'', 1964) reflects within her own ''conscience'' about her mother's attempts to develop such a moral sympathy and understanding of others.<ref>Simone de Beauvoir. ''A Very Easy Death''. Penguin Books. London. 1982. {{ISBN|0-14-002967-2}}. p. 60</ref> |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

| width = 30em |

|||

| bgcolor = #c6dbf7 |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| quote = "The sight of her tears grieved me; but I soon realised that she was weeping over her failure, without caring about what was happening inside me ... We might still have come to an understanding if, instead of asking everybody to pray for my soul, she had given me a little confidence and sympathy. I know now what prevented her from doing so: she had too much to pay back, too many wounds to salve, to put herself in another's place. In actual doing she made every sacrifice, but her feelings did not take her out of herself. Besides, how could she have tried to understand me since she avoided looking into her own heart? As for discovering an attitude that would not have set us apart, nothing in her life had ever prepared her for such a thing: the unexpected sent her into a panic, because she had been taught never to think, act or feel except in a ready-made framework." |

|||

| source = — Simone de Beauvoir. ''A Very Easy Death''. Penguin Books. London. 1982. p. 60. |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Michael Walzer]] claimed that the growth of religious toleration in Western nations arose amongst other things, from the general recognition that private conscience signified some inner divine presence regardless of the religious faith professed and from the general respectability, piety, self-limitation, and sectarian discipline which marked most of the men who claimed the rights of conscience.<ref>Michael Walzer. ''Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War and Citizenship''. Clarion-Simon and Schuster. New York. 1970. p. 124.</ref> Walzer also argued that attempts by courts to define conscience as a merely personal moral code or as sincere belief, risked encouraging an anarchy of moral egotisms, unless such a code and motive was necessarily tempered with shared moral knowledge: derived either from the connection of the individual to a universal spiritual order, or from the common principles and mutual engagements of unselfish people.<ref>Michael Walzer. ''Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War and Citizenship''. Clarion-Simon and Schuster. New York. 1970. p. 131</ref> [[Ronald Dworkin]] maintains that constitutional protection of [[freedom of conscience]] is central to democracy but creates personal duties to live up to it: "Freedom of conscience presupposes a personal responsibility of reflection, and it loses much of its meaning when that responsibility is ignored. A good life need not be an especially reflective one; most of the best lives are just lived rather than studied. But there are moments that cry out for self-assertion, when a passive bowing to fate or a mechanical decision out of deference or convenience is treachery, because it forfeits dignity for ease."<ref>Ronald Dworkin. ''Life's Dominion''. Harper Collins, London 1995. pp. 239–40</ref> [[Edward Conze]] stated it is important for individual and collective moral growth that we recognise the illusion of our conscience being wholly located in our body; indeed both our conscience and wisdom expand when we act in an unselfish way and conversely "repressed compassion results in an unconscious sense of guilt."<ref>Edward Conze. ''Buddhism: Its Essence and development''. Harper Torchbooks. New York. 1959. pp. 20 and 46</ref> |

|||

[[File:Peter Singer - Effective Altruism -Melb Australia Aug 2015.jpg|left|thumb|[[Peter Singer]]: distinguished between immature "traditional" and highly reasoned "critical" conscience]] |

|||

The philosopher [[Peter Singer]] considers that usually when we describe an action as conscientious in the critical sense we do so in order to deny either that the relevant agent was motivated by selfish desires, like greed or ambition, or that he acted on whim or impulse.<ref>Peter Singer. ''Democracy and Disobedience''. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1973. p. 94.</ref> |

|||

Moral anti-realists debate whether the moral facts necessary to activate conscience [[supervenience|supervene]] on natural facts with ''[[Empirical evidence|a posteriori]]'' necessity; or arise ''a priori'' because moral facts have a primary intension and naturally identical worlds may be presumed morally identical.<ref>David Chalmers. ''The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory''. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 1996 pp. 83–84</ref> It has also been argued that there is a measure of [[moral luck]] in how circumstances create the obstacles which ''conscience'' must overcome to apply moral principles or human rights and that with the benefit of enforceable property rights and the [[rule of law]], access to [[universal health care]] plus the absence of high adult and [[infant mortality]] from conditions such as [[malaria]], [[tuberculosis]], [[HIV/AIDS]] and [[famine]], people in relatively prosperous developed countries have been spared pangs of ''conscience'' associated with the physical necessity to steal scraps of food, bribe tax inspectors or police officers, and commit murder in [[guerrilla]] wars against corrupt government forces or rebel armies.<ref>Nicholas Fearn. ''Philosophy: The Latest Answers to the Oldest Questions''. Atlantic Books. London. 2005. pp. 176–177.</ref> [[Roger Scruton]] has claimed that true understanding of ''conscience'' and its relationship with ''morality'' has been hampered by an "impetuous" belief that philosophical questions are solved through the analysis of language in an area where clarity threatens vested interests.<ref>Roger Scruton. ''Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey''. Mandarin. London. 1994. p. 271</ref> [[Susan Sontag]] similarly argued that it was a symptom of [[psychological]] immaturity not to recognise that many morally immature people willingly experience a form of delight, in some an erotic breaking of [[taboo]], when witnessing violence, suffering and pain being inflicted on others.<ref>Susan Sontag. ''Regarding the Pain of Others''. Hamish Hamilton, London. 2003. {{ISBN|0-241-14207-5}} pp. 87 and 102.</ref> [[Jonathan Glover]] wrote that most of us "do not spend our lives on endless landscape gardening of our self" and our ''conscience'' is likely shaped not so much by heroic struggles, as by choice of partner, friends and job, as well as where we choose to live.<ref>Jonathan Glover. ''I: The Philosophy and Psychology of Personal Identity''. Penguin Books, London. 1988. p. 132.</ref> [[Garrett Hardin]], in a famous article called "[[The Tragedy of the Commons]]", argues that any instance in which society appeals to an individual exploiting a commons to restrain himself or herself for the general good—by means of his or her ''conscience''—merely sets up a system which, by selectively diverting societal power and physical resources to those lacking in ''conscience'', while fostering guilt (including anxiety about his or her individual contribution to over-population) in people acting upon it, actually works toward the elimination of conscience from the race.<ref name="hardin68">Garrett Hardin, [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/162/3859/1243 "The Tragedy of the Commons"], ''Science'', Vol. 162, No. 3859 (13 December 1968), pp. 1243–48. Also available here [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/162/3859/1243.pdf] and [http://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles/art_tragedy_of_the_commons.html here.] |

|||

</ref><ref>Scott James Shackelford. 2008. [https://ssrn.com/abstract=1407332 "The Tragedy of the Common Heritage of Mankind"]. Retrieved 30 October 2009.</ref> |

|||

[[File:John Ralston Saul.jpg|left|thumb|upright|[[John Ralston Saul]]: consumers risk turning over their conscience to technical experts and to the ideology of free markets]] |

|||

[[John Ralston Saul]] expressed the view in ''The Unconscious Civilization'' that in contemporary developed nations many people have acquiesced in turning over their sense of right and wrong, their ''critical conscience'', to technical experts; willingly restricting their moral freedom of choice to limited consumer actions ruled by the ideology of the free market, while citizen participation in public affairs is limited to the isolated act of voting and private-interest lobbying turns even elected representatives against the public interest.<ref>John Ralston Saul. ''The Unconscious Civilisation''. Massey Lectures Series. Anansi Pres, Toronto. 1995. {{ISBN|0-88784-586-X}} pp. 17, 81 and 172.</ref> |

|||

Some argue on religious or philosophical grounds that it is blameworthy to act against ''conscience'', even if the judgement of ''conscience'' is likely to be erroneous (say because it is inadequately informed about the facts, or prevailing moral (humanist or religious), professional ethical, legal and human rights norms).<ref>Alan Donagan. ''The Theory of Morality''. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. 1977. pp. 131–38.</ref> Failure to acknowledge and accept that conscientious judgements can be seriously mistaken, may only promote situations where one's conscience is manipulated by others to provide unwarranted justifications for non-virtuous and selfish acts; indeed, insofar as it is appealed to as glorifying ideological content, and an associated extreme level of devotion, without adequate constraint of external, altruistic, normative justification, '''conscience''' may be considered morally blind and dangerous both to the individual concerned and humanity as a whole.<ref>Beauchamp TL and Childress JF. ''Principles of Biomedical Ethics''. 4th ed. Oxford University Press, New York. 1994 pp. 478–79.</ref> Langston argues that philosophers of [[virtue ethics]] have unnecessarily neglected ''conscience'' for, once conscience is trained so that the principles and rules it applies are those one would want all others to live by, its practise cultivates and sustains the virtues; indeed, amongst people in what each society considers to be the highest state of moral development there is little disagreement about how to act.<ref name="autogenerated176"/> [[Emmanuel Levinas]] viewed conscience as a revelatory encountering of resistance to our selfish powers, developing morality by calling into question our naive sense of [[freedom of will]] to use such powers arbitrarily, or with [[violence]], this process being more severe the more rigorously the goal of our self was to obtain control.<ref name="Levinas">Emmanuel Levinas. ''Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority''. Lingis A (trans) Duquesne University Press, Pittsburgh, PA 1998. pp. 84, 100–01</ref> |

|||

In other words, the welcoming of the ''Other'', to Levinas, was the very essence of ''conscience'' properly conceived; it encouraged our ego to accept the fallibility of assuming things about other people, that selfish [[freedom of will]] "does not have the last word" and that realising this has a transcendent purpose: "I am not alone ... in conscience I |

|||

'''Ethics''' or '''moral philosophy''' is the philosophical study of [[Morality|moral]] phenomena. It investigates [[Normativity|normative]] questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. It is usually divided into three major fields: [[normative ethics]], [[applied ethics]], and [[metaethics]]. |

|||

Normative ethics tries to discover and [[Justification (epistemology)|justify]] universal principles that govern how people should act in any situation. According to [[Consequentialism|consequentialists]], an act is right if it leads to the best consequences. [[Deontology|Deontologists]] hold that morality consists in fulfilling [[Duty|duties]], like telling the truth and keeping promises. [[Virtue theory|Virtue theorists]] see the manifestation of [[virtue]]s, like [[courage]] and [[compassion]], as the fundamental principle of morality. Applied ethics examines concrete ethical problems in real-life situations, for example, by exploring the moral implications of the universal principles discovered in normative ethics within a specific domain. [[Bioethics]] studies moral issues associated with [[Life|living organisms]] including humans, animals, and plants. [[Business ethics]] investigates how ethical principles apply to corporations, while [[professional ethics]] focuses on what is morally required of members of different [[profession]]s. Metaethics is a [[metatheory]] that examines the underlying assumptions and concepts of ethics. It asks whether moral facts have [[Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy)|mind-independent]] existence, whether moral statements can be true, how it is possible to acquire moral knowledge, and how moral judgments motivate people. |

|||