Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra | |

|---|---|

portrait of Cervantes[a] by Juan Martínez de Jáuregui y Aguilar (c. 1600), reportedly apocryphal | |

| Born | September 29, 1547 Alcalá de Henares, Spain |

| Died | April 23, 1616, age 68 Madrid, Spain |

| Occupation | novelist, poet and playwright |

Don Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra[b] (IPA: [miˈɣel ðe θerˈβantes saaˈβeðra] in modern Spanish; September 29, 1547 – April 23, 1616) was a Spanish novelist, poet, and playwright. Cervantes was one of the most important and influential persons in literature and the leading figure associated with the cultural flourishing of sixteenth century Spain (the Siglo de Oro). His novel, Don Quixote, is considered as a Spanish founding classic of Western literature and regularly figures among the best novels ever written; it has been translated into more than sixty-five languages, while editions continue regularly to be printed, and critical discussion of the work has persisted unabated since the 18th century.[1]. He has been dubbed el Príncipe de los Ingenios (the Prince of Wits).

Cervantes, born in Alcalá de Henares, was the fourth of seven children in a family whose origins may have been of the minor gentry. The family moved from town to town, and little is known of Cervantes's early years. Cervantes made his literary début in 1568. By 1570 he had enlisted as a soldier in a Spanish infantry regiment and continued his military life until 1575, when he was captured by barbary pirates on his return home. He was ransomed by his parents and the Trinitarians and returned to his family in Madrid.

In 1585, Cervantes published a pastoral novel, La Galatea. Because of financial problems, Cervantes worked as a purveyor for the Spanish Armada, and later as a tax collector. In 1597 discrepancies in his accounts of three years previous landed him in the Crown Jail of Seville. In 1605 he was in Valladolid, just when the immediate success of the first part of his Don Quixote, published in Madrid, signaled his return to the literary world. In 1607, he settled in Madrid, where he lived and worked until his death. During the last nine years of his life, Cervantes solidified his reputation as a writer; he published the Exemplary Novels (Novelas ejemplares) in 1613, the Journey to Parnassus (Viaje del Parnaso) in 1614, and in 1615, the Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses and the second part of Don Quixote. Carlos Fuentes noted that, "Cervantes leaves open the pages of a book where the reader knows himself to be written. "[2]

Biography

Family and Early Life

Cervantes was born at Alcalá de Henares, a castilian city about 20 miles from Madrid, probably on September 29 (the feast day of St. Michael) 1547. He was baptized on October 9.[1] Miguel's paternal great-grandfather was Ruy Díaz de Cervantes, a prosperous draper who was born most probably in the 1430s. He married a Catalina de Cabrera about whom nothing at all is known. Their son, Miguel's grandfather Juan studied law at University of Salamanca, for most of his life he served as a minor magistrate, ended his career as a specialist in fiscal law for the Spanish Inquisition and was a well-to-do man. He married Leonor Fernández de Torreblanca; she was probably Juan's cousin. She was a daughter of Cordoban physician. Miguel's father, Ruy (Rodrigo), was a barber-surgeon who set bones, performed bloodlettings, and attended "lesser medical needs". He presented himself as a nobleman and liked to act as a gentleman, which was not easy because of his low income.[3] Cervantes's mother seems to have been a descendant of Jewish converts to Christianity.[4] Little is known of Cervantes' early years and education, but it seems that he spent much of his childhood moving from town to town with his family. While some of his biographers argue that he studied at the University of Salamanca, there is no solid evidence for supposing that he did so.[c] There has been speculation also that Cervantes studied with the Jesuits in Córdoba or Sevilla.[5]

All that we know positively about his education is that humanist Juan López de Hoyos called him his "dear and beloved pupil." This was in a little collection of verses by different hands on the death of Isabel de Valois, second queen of Philip II of Spain, published by López de Hoyos in 1569, to which Cervantes contributed four pieces, including an elegy, and an epitaph in the form of a sonnet.[6] That same year he left Spain for Italy;[7] it seems that for a time he served as chamberlain in the household of Cardinal Giulio Acquaviva in Rome.

Soldier and captive

The reasons that forced Cervantes to leave Castilia remain unclear. Whether he was the "student" of the same name, a "sword-wielding fugitive from justice", fleeing from the royal warrant of arrest for having wounded a certain Antonio de Sigura in a duel is another mystery. This fugitive was condemned "by default to having his right hand publicly cut off and to banishment from the realm for ten years".[8] In any event, in going to Italy Cervantes was doing what many young Spaniards of the time did to further their careers in one way or another. Rome would reveal to the young artist its ecclesiastic pomp, ritual and majesty. In a city teeming with ruins, Cervantes could focus his attention on Renaissance art, architecture and poetry (knowledge of Italian literature is so readily discernible in his own productions), and on rediscovering antiquity; he could find in the ancients "a powerful impetus to revive the contemporary world in light of its accomplishments".[9] Thus, Cervantes' continuing desire for Italy, as revealed in his later works, was in part a desire for a return to Renaissance.[10]

By 1570 Cervantes had enlisted as a soldier in a Castilia infantry regiment stationed in Naples, then a possession of the Castilian crown. He was there for about a year before he saw active service. In September 1571, Cervantes sailed on board the Marquesa, part of the galley fleet of the Holy League (a coalition of the Pope, Spain, Venice, Republic of Genoa, Duchy of Savoy, the Knights of Malta and others under the command of John of Austria) that defeated the Ottoman fleet on October 7 in the Gulf of Lepanto near Corinth. Though taken down with fever, Cervantes refused to stay below, and begged to be allowed to take part in the battle, saying that he would rather die for his God and his king than keep under cover. He fought bravely on board a vessel, and received three gunshot wounds – two in the chest and one which rendered his left hand useless for the rest of his life. In Journey to Parnassus, he was to say that he "had lost the movement of the left hand for the glory of the right" (he was thinking of the success of the first part of Don Quixote). Cervantes always looked back on his conduct in the battle with pride: he believed that he had taken part in an event that would shape the course of European history.[7]

| "What I cannot help taking amiss is that he[d] charges me with being old and one-handed, as if it had been in my power to keep time from passing over me, or as if the loss of my hand had been brought about in some tavern, and not on the grandest occasion the past or present has seen, or the future can hope to see. If my wounds have no beauty to the beholder's eye, they are, at least, honourable in the estimation of those who know where they were received; for the soldier shows to greater advantage dead in battle than alive in flight." |

| Miguel de Cervantes (Don Quixote - Part II, "The Author's Preface" translated by John Ormsby) |

After the battle of Lepanto Cervantes remained in hospital for nearly six months, before his wounds were sufficiently healed to allow his joining the colors again.[11] From 1572 to 1575, based mainly in Naples, he continued his soldier's life; he participated in expeditions to Corfu and Navarino, and saw the fall of Tunis and La Goleta to the Turks in 1574.[12]

On September 6 or 7 1575 Cervantes set sail on the galley Sol from Naples to Barcelona, Spain, with letters of commendation to the king from the duke de Sessa and Don Juan himself.[13] On the morning of September 26, as the Sol approached the Catalan coast, it was attacked by Algerian corsairs. After significant resistance, in which the captain and many crew members were killed, the surviving passengers were taken to Algiers as captives.[14] After five years spent as a slave in Algiers, and four unsuccessful escape attempts, he was ransomed by his parents and the Trinitarians and returned to his family in Madrid. Not surprisingly, this period of Cervantes' life supplied subject matter for several of his literary works, notably the Captive's tale in Don Quixote and the two Algiers plays, El trato de Argel (The Traffic of Algiers) and Los baños de Argel (The Bathrooms of Algiers), as well as episodes in a number of other writings, although never in straight autobiographical form.[1]

Literary pursuits

In 1584, he married the much younger Catalina de Salazar y Palacios. During the next 20 years he led a nomadic existence, working as a purchasing agent for the Spanish Armada, and as a tax collector. He suffered a bankruptcy, and was imprisoned at least twice (1597 and 1602) because of irregularities in his accounts, one due rather to some subordinate than to himself. Between the years 1596 and 1600, he lived primarily in Seville. In 1606, Cervantes settled permanently in Madrid, Spain; where he remained for the rest of his life. In 1585, Cervantes published his first major work, La Galatea, a pastoral romance, at the same time that some of his plays, now lost except for El trato de Argel (where he dealt with the life of Christian slaves in Algiers) and El cerco de Numancia, were playing on the stages of Madrid. La Galatea received little contemporary notice, and Cervantes never wrote the continuation for it, (which he repeatedly promised). Cervantes next turned his attention to the drama, hoping to derive an income from that source, but the plays which he composed failed to achieve their purpose. Aside from his plays, his most ambitious work in verse was Viaje del Parnaso (1614), an allegory which consisted largely of a rather tedious though good-natured review of contemporary poets. Cervantes himself realized that he was deficient in poetic gifts.

If a remark which Cervantes himself makes in the prologue of Don Quixote is to be taken literally, the idea of the work, though hardly the writing of its "First Part", as some have maintained, occurred to him in prison at Argamasilla de Alba, in La Mancha. Cervantes' idea was to give a picture of real life and manners, and to express himself in clear language. The intrusion of everyday speech into a literary context was acclaimed by the reading public. The author stayed poor until 1605, when the first part of Don Quixote appeared. Although it did not make Cervantes rich, it brought him international appreciation as a man of letters. Cervantes also wrote many plays, only two of which have survived; short novels, and the vogue obtained by Cervantes's story led to the publication of a continuation of it by an unknown who masqueraded under the name of Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. In self-defence, Cervantes produced his own continuation, or "Second Part", of Don Quixote, which made its appearance in 1615.

For the world at large, interest in Cervantes centers particularly in Don Quixote, and this work has been regarded chiefly as a novel of purpose. It is stated again and again that he wrote it in order to ridicule the romances of chivalry, and to destroy the popularity of a form of literature which for much more than a century had engrossed the attention of a large proportion of those who could read among his countrymen, and which had been communicated by them to the ignorant.

Don Quixote certainly reveals much narrative power, considerable humor, a mastery of dialogue, and a forcible style. Of the two parts written by Cervantes, the first has ever remained the favourite. The second part is inferior to it in humorous effect; but, nevertheless, the second part shows more constructive insight, better delineation of character, an improved style, and more realism and probability in its action.

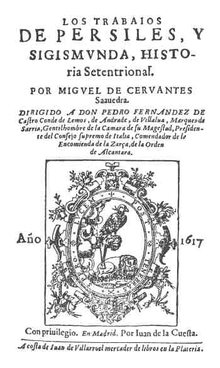

In 1613, he published a collection of tales, the Exemplary Novels, some of which had been written earlier. On the whole, the Exemplary Novels are worthy of the fame of Cervantes; they bear the same stamp of genius as Don Quixote. The picaroon strain, already made familiar in Spain by the Lazarillo de Tormes and his successors, appears in one or another of them, especially in the Rinconete y Cortadillo, which is the best of all. He also published the Viaje del Parnaso in 1614, and in 1615, the Eight Comedies and Eight New Interludes. At the same time, Cervantes continued working on Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, a novel of adventurous travel completed just before his death, and which appeared posthumously in January, 1617.

Death

Cervantes died in Madrid on April 23, 1616; coincidentally William Shakespeare also died on that date, but not on the same day; Britain was still using the Julian calendar, whereas Spain had already adopted the Gregorian calendar.[15] In honour of this coincidence UNESCO established April 23 as the International Day of the Book.[16] It is worth mentioning that the Encyclopedia Hispanica claims the date widely quoted as Cervantes' date of death, namely April 23, is the date on his tombstone which in accordance of the traditions at the time would be his date of burial rather than date of death. If this is true, according to Hispanica, then it means that Cervantes probably died on April 22 and was buried on April 23.

Works

Novels

Cervantes's novels, listed chronologically, are:

- La Galatea (1585), a pastoral romance in prose and verse based upon the genre introduced into Spain by Jorge de Montemayor's Diana (1559). Its theme is the fortunes and misfortunes in love of a number of idealized shepherds and shepherdesses, who spend their life singing and playing musical instruments.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha I (1605)

- Novelas ejemplares (1613), a collection of twelve short stories of varied types about the social, political, and historical problems of the Cervantes' Spain:

- La gitanilla(The Gypsy Girl)

- El amante liberal (The Generous Lover)

- Rinconete y Cortadillo

- La española inglesa (The English Spanish Lady)

- El licenciado Vidriera (Vidriera, the Lawyer)

- La fuerza de la sangre (The Power of Blood)

- El celoso extremeño (The Jealous Old Man From Extremadura)

- La ilustre fregona (The Illustrious Kitchen-Maid)

- Novela de las dos doncellas (The Two Damsels)

- Novela de la señora Cornelia (Lady Cornelia)

- Novela del casamiento engañoso (The Deceitful Marriage)

- El coloquio de los perros (The Dialogue of the Dogs)

- Segunda parte del ingenioso caballero don Quijote de la Mancha (1615)

- Los trabajos de Persiles y Segismunda, historia septentrional, The Labours of Persiles and Sigismunda: A Northern Story (1617).

- Los trabajos is the best evidence not only of the survival of Byzantine novel themes but also of the survival of forms and ideas of the Spanish novel of the second Renaissance. In this work, published after the author's death, Cervantes relates the ideal love and unbelievable vicissitudes of a couple who, starting from the Arctic regions, arrive in Rome, where they find a happy ending for their complicated adventures.

Don Quixote

Don Quixote (sometimes spelled "Quijote") is actually two separate books that cover the adventures of Don Quixote, also known as the knight or man of La Mancha, a hero who carries his enthusiasm and self-deception to unintentional and comic ends. On one level, Don Quixote works as a satire of the romances of chivalry which ruled the literary environment of Cervantes' time. However, the novel also allows Cervantes to illuminate various aspects of human nature by using the ridiculous example of the delusional Quixote.

Because the novel - particularly the first part - was written in individually published sections, the composition includes several incongruities. In the preface to the second part, Cervantes himself pointed out some of these errors, but he disdained to correct them, because he conceived that they had been too severely condemned by his critics.

Cervantes felt a passion for the vivid painting of character, as his successful works prove. Under the influence of this feeling, he drew the natural and striking portrait of his heroic Don Quixote, so truly noble-minded, and so enthusiastic an admirer of everything good and great, yet having all those fine qualities, accidentally blended with a relative kind of madness; and he likewise portrayed with no less fidelity, the opposite character of Sancho Panza, a compound of grossness and simplicity, whose low self-esteem leads him to place blind confidence in all the extravagant hopes and promises of his master. The subordinate characters of the novel exhibit equal truth and decision.

A translator can not commit a more serious injury to Don Quixote than to dress that work in a light, anecdotal style[citation needed]. A style perfectly unostentatious and free from affectation, but at the same time solemn, and penetrated, as it were, with the character of the hero, diffuses over this comic romance an imposing air, which, were it not so appropriate, would seem to belong exclusively to serious works and which is certainly difficult to capture in a translation. Yet it is precisely this solemnity of language which imparts a characteristic relief to the comic scenes[citation needed]. It is the genuine style of the old romances of chivalry, improved and applied in a totally original way; and only where dialogue style occurs is each person found to speak as he might be expected to do, and in his own peculiar manner. But wherever Don Quixote himself harangues, the language re-assumes the venerable tone of the romantic style; and various uncommon expressions used by the hero serve to complete the delusion of his covetous squire, to whom they are only half intelligible. This characteristic tone diffuses over the whole a poetic colouring, which distinguishes Don Quixote from all comic romances of the ordinary style; and that poetic colouring is moreover heightened by the judicious choice of episodes.

The essential connection of these episodes with the whole has sometimes escaped the observation of critics, who have regarded as merely parenthetical those parts in which Cervantes has most decidedly manifested the poetic spirit of his work. The novel of El curioso impertinente cannot indeed be ranked among the number of these essential episodes, but the charming story of the shepherdess Marcella, the history of Dorothea, and the history of the rich Camacho and the poor Basilio, are unquestionably connected with the interest of the whole.

These serious romantic parts, which are not, it is true, essential to the narrative connexion, but strictly belong to the characteristic dignity of the whole picture[citation needed], also prove how far Cervantes was from the idea usually attributed to him of writing a book merely to excite laughter. The passages, which common readers feel inclined to pass over[citation needed], are, in general, precisely those in which Cervantes is most decidedly a poet, and for which he has manifested an evident predilection. On such occasions, he also introduces among his prose, episodical verses, for the most part excellent in their kind and no translator can omit them without doing violence to the spirit of the original.

Were it not for the happy art with which Cervantes has contrived to preserve an intermediate tone between pure poetry and prose, Don Quixote would not deserve to be cited as the first classic model of the modern romance or novel. It is, however, fully entitled to that distinction. Cervantes was the first writer who formed the genuine romance of modern times on the model of the original chivalrous romance that equivocal creation of the genius and the barbarous taste of the Middle Ages. The result has proved that modern taste, however readily it may in other respects conform to the rules of the antique, nevertheless requires, in the narration of fictitious events, a certain union of poetry with prose, which was unknown to the Greeks and Romans in their best literary ages[citation needed]. It was only necessary to seize on the right tone, but that was a point of delicacy, which the inventors of romances of chivalry were not able to comprehend. Diego de Mendoza, in his Lazarillo de Tormes, departed too far from poetry. Cervantes, in his Don Quixote restored to the poetic art the place it was entitled to hold in this class of writing; and he must not be blamed if cultivated nations have subsequently mistaken the true spirit of this work, because their own novelists had led them to regard common prose as the style peculiarly suited to romance composition.

Don Quixote is, moreover, the undoubted prototype of the comic novel. The humorous situations are, it is true, almost all burlesque, which was certainly not necessary, but the satire is frequently so delicate, that it escapes rather than obtrudes on unpractised attention; as for example, in the whole picture of the administration of Sancho Panza in his imaginary island. The language, even in the description of the most burlesque situations, never degenerates into vulgarity; it is on the contrary, throughout the whole work, so noble, correct and highly polished, that it would not disgrace even an ancient classic of the first rank[citation needed]. This explanation of a part of the merits of a work, which has been so often wrongly judged, may perhaps seem belong rather to the eulogist than the calm and impartial historian. Let those who may he inclined to form this opinion study Don Quixote in the original language, and study it rightly, for it is not a book to be judged by a superficial perusal[citation needed]. But care must be taken lest the intervention of many subordinate traits, which were intended to have only a transient national interest, should produce an error in the estimate of the whole. By the 20th century it became clear that Don Quixote was the first true modern novel, a systemical and structural masterpiece.

Don Quixote is one of the Encyclopedia Britannica's "Great Books of the Western World" and the Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky called it "the ultimate and most sublime word of human thinking". Notably, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion learned the Spanish language so that he could read it in the original[citation needed], considering it a prerequisite to becoming an effective statesman.

La Galatea

La Galatea, the pastoral romance, which Cervantes wrote in his youth, is an imitation of the Diana of Jorge de Montemayor, and bears an even closer resemblance to Gil Polo's continuation of that romance. Next to Don Quixote and the Novelas exemplares, it is particularly worthy of attention, as it manifests in a striking way the poetic direction in which the genius of Cervantes moved even at an early period of life.

Novelas ejemplares

It would be scarcely possible to arrange the other works of Cervantes according to a critical judgment of their importance; for the merits of some consist in the admirable finish of the whole, while others exhibit the impress of genius in the invention, or some other individual feature.

A distinguished place must, however, be assigned to the Novelas[17] ejemplares ("Moral or Instructive Tales"). They are unequal in merit as well as in character. Cervantes doubtless intended that they should be to the Spaniards nearly what the novellas of Boccaccio were to the Italians, some are mere anecdotes, some are romances in miniature, some are serious, some comic, and all are written in a light, smooth, conversational style.

Four of them are perhaps of less interest than the rest: El amante liberal, La señora Cornelia, Las dos doncellas and La española inglesa. The theme common to these is basically the traditional one of the Byzantine novel: pairs of lovers separated by lamentable and complicated happenings are finally reunited and find the happiness they have longed for. The heroines are all of most perfect beauty and of sublime morality; they and their lovers are capable of the highest sacrifices, and they exert their souls in the effort to elevate themselves to the ideal of moral and aristocratic distinction which illuminates their lives.

In El amante liberal, to cite an example, the beautiful Leonisa and her lover Ricardo are carried off by Turkish pirates; both fight against serious material and moral dangers; Ricardo conquers all obstacles, returns to his homeland with Leonisa, and is ready to renounce his passion and to hand Leonisa over to her former lover in an outburst of generosity; but Leonisa's preference naturally settles on Ricardo in the end.

Another group of "exemplary" novels is formed by La fuerza de la sangre, La ilustre fregona, La gitanilla, and El celoso extremeño. The first three offer examples of love and adventure happily resolved, while the last unravels itself tragically. Its plot deals with the old Felipe Carrizales, who, after traveling widely and becoming rich in America, decides to marry, taking all the precautions necessary to forestall being deceived. He weds a very young girl and isolates her from the world by having her live in a house with no windows facing the street; but in spite of his defensive measures, a bold youth succeeds in penetrating the fortress of conjugal honor, and one day Carrizales surprises his wife in the arms of her seducer. Surprisingly enough he pardons the adulterers, recognizing that he is more to blame than they, and dies of sorrow over the grievous error he has committed. Cervantes here deviated from literary tradition, which demanded the death of the adulterers, but he transformed the punishment inspired by the social ideal of honour into a criticism of the responsibility of the individual.

Rinconete y Cortadillo, El casamiento engañoso, El licenciado Vidriera and El coloquio de los perros, four works of art which are concerned more with the personalities of the characters who figure in them than with the subject matter, form the final group of these stories. The protagonists are two young vagabonds, Rincón and Cortado; Lieutenant Campuzano; a student, Tomás Rodaja, who goes mad and believes himself to have been changed into a witty man of glass, offering Cervantes the opportunity to chain witty jokes; and finally two dogs, Cipión and Berganza, whose wandering existence serves as a mirror for the most varied aspects of Spanish life. Rinconete y Cortadillo is one of the most delightful of Cervantes' works. Its two young vagabonds come to Seville attracted by the riches and disorder that the sixteenth-century commerce with the Americas had brought to that metropolis. There they come into contact with a brotherhood of thieves led by the unforgettable Monipodio, whose house is the headquarters of the Sevillian underworld. Under the bright Andalusian sky, persons and objects take form with the brilliance and subtle drama of a Velazquez, and a distant and discreet irony endows the figures, insignificant in themselves, as they move within a ritual pomp that is in sharp contrast with their morally deflated lives. When Monipodio appears, serious and solemn among his silent subordinates, "all who were looking at him performed a deep, protracted bow." Rincón and Cortado had initiated their mutual friendship beforehand "with saintly and praiseworthy ceremonies." The solemn ritual of this band of ruffians is all the more comic for being concealed in Cervantes' drily humorous style.

Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda

The romance of Persiles and Sigismunda, which Cervantes finished shortly before his death, must be regarded as an interesting appendix to his other works. The language and the whole composition of the story exhibit the purest simplicity, combined with singular precision and polish. The idea of this romance was not new, and scarcely deserved to be reproduced in a new manner. But it appears that Cervantes, at the close of his glorious career, took a fancy to imitate Heliodorus. He has maintained the interest of the situations, but the whole work is merely a romantic description of travels, rich enough in fearful adventures, both by sea and land. Real and fabulous geography and history are mixed together in an absurd and monstrous manner; and the second half of the romance, in which the scene is transferred to Spain and Italy, does not exactly harmonize with the spirit of the first half.

Poetry

Some of his poems are found in La Galatea. He also wrote Dos canciones a la armada invencible. His best work, however, is found in the sonnets, particularly Al túmulo del rey Felipe en Sevilla. Among his most important poems, Canto de Calíope, Epístola a Mateo Vázquez, and the Viaje del Parnaso (Journey to Parnassus), (1614) stand out. The latter is his most ambitious work in verse, an allegory which consists largely of reviews of contemporary poets.

Compared to the novelist, Cervantes is often considered a mediocre poet. Should one cast a glance on the collected works of Cervantes, in order to ascertain what their author was entitled to claim as his original property, independently of his contemporaries and predecessors, we shall find that the genius of that poet, who is in general only partially estimated, shines with the finer lustre the longer it is contemplated. That kind of criticism that is to be learned, contributed but little to the development and formation of his genius. A critical tact, which is a truer guide than any rule, but which abandons genius when it forgets itself, secured the fancy of Cervantes against the aberrations of common minds, and his sportive wit was always subject to the control of solid judgement. The vanity, which occasionally made him mistake the true bent of his talent, must be confessed to have been pardonable, considering how little he was known to his contemporaries. He did not even know himself, though he felt the consciousness of his genius. From the mental height to which he had raised himself, he might, without too highly rating his own abilities, look down on all the writers of his age. More than one poet of great, of immortal genius, might be placed beside him in his own country; but of all the Spanish poets, Cervantes alone belongs to the whole world.

Viaje del Parnaso

The prose of the Galatea, which is in other respects so beautiful, is also occasionally overloaded with epithet. Cervantes displays a totally different kind of poetic talent in the Viaje del Parnaso, a work which cannot properly be ranked in any particular class of literary composition, but which, next to Don Quixote, is the most exquisite production of its author.

Plays

Comparisons have also diminished the reputation of his plays, but two of them, El trato de Argel and La Numancia, (1582), made a big impact and were not surpassed until Lope de Vega appeared.

The first of these is written in five acts; based on his experiences as a Moorish captive, Cervantes dealt with the life of Christian slaves in Algiers. The other play, Numancia is a description of the siege of Numantia by the Romans stuffed with horrors and described as utterly devoid of the requisites of dramatic art.

Cervantes's later production consists of 16 dramatic works, among which eight full-length plays:

El gallardo español, Los baños de Argel, La gran sultana, Doña Catalina de Oviedo, La casa de los celos, El laberinto del jamon, the cloak and dagger play La Entretenida, El rufián dichoso and Pedro de Urdemalas, a sensitive play about a pícaro who joins a group of Gypsies for love of a girl.

He also wrote eight short farces (entremeses) : El juez de los divorcios, El rufián viudo llamado Trampagos, La elección de los alcaldes de Daganzo, La guarda cuidadosa (The Vigilant Sentinel), El vizcaíno fingido, El retablo de las maravillas, La cueva de Salamanca, and El viejo celoso (The Jealous Old Man).

These plays and entremeses made up Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses nuevos, nunca representados (Eight comedies and Eight New Interludes) , which appeared in 1615. Cervantes's entremeses, whose dates and order of composition are not known, must not have been performed in their time. Faithful to the spirit of Lope de Rueda, Cervantes endowed them with novelistic elements such as simplified plot, the type of description normally associated with the novel, and character development. The dialogue is sensitive and agile.

Cervantes includes some of his dramas among those productions with which he was himself most satisfied; and he seems to have regarded them with the greater self-complacency in proportion as they experienced the neglect of the public. This conduct has sometimes been attributed to a spirit of contradiction, and sometimes to vanity. That the penetrating and profound Cervantes should have so mistaken the limits of his dramatic talent, would not be sufficiently accounted for, had he not unquestionably proved by his tragedy of Numantia how pardonable was the self-deception of which he could not divest himself.

Cervantes was entitled to consider himself endowed with a genius for dramatic poetry; but he could not preserve his independence in the conflict he had to maintain with the conditions required by the Spanish public in dramatic composition; and when he sacrificed his independence, and submitted to rules imposed by others, his invention and language were reduced to the level of a poet of inferior talent. The intrigues, adventures and surprises, which in that age characterized the Spanish drama, were ill suited to the genius of Cervantes. His natural style was too profound and precise to be reconciled to fantastical ideas, expressed in irregular verse. But he was Spaniard enough to be gratified with dramas, which, as a poet, he could not imitate; and he imagined himself capable of imitating them, because he would have shone in another species of dramatic composition, had the public taste accommodated itself to his genius.

La Numancia

This play is a dramatization of the long and brutal siege of the Celtiberian town Numantia, Hispania, by the Roman forces of Scipio Africanus.

Cervantes invented along with the subject of his piece a peculiar style of tragic composition, in doing which he did not pay much regard to the theory of Aristotle. His object was to produce a piece full of tragic situations, combined with the charm of the marvellous. In order to accomplish this goal, Cervantes relied heavily on allegory and on mythological elements.

The tragedy is written in conformity with no rules save those which the author prescribed to himself; for he felt no inclination to imitate the Greek forms. The play is divided into four acts, (jornadas) and no chorus is introduced. The dialogue is sometimes in tercets and sometimes in redondillas, and for the most part in octaves without any regard to rule.

Cervantes' historical importance and influence

Cervantes' novel Don Quixote has had a tremendous influence on the development of prose fiction; it has been translated into all modern languages and has appeared in 700 editions. The first translation in English, and also in any language, was made by Thomas Shelton in 1608, but not published until 1612. Shakespeare had evidently read Don Quixote, but it is most unlikely that Cervantes had ever heard of Shakespeare. Carlos Fuentes raised the possibility that Cervantes and Shakespeare were the same person (see Shakespearean authorship question). Francis Carr has suggested that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare's plays and Don Quixote.[18]

Don Quixote has been the subject of a variety of works in other fields of art, including operas by the Italian composer Giovanni Paisiello, the French Jules Massenet, and the Spanish Manuel de Falla; a tone poem by the German composer Richard Strauss; a German film (1933) directed by G. W. Pabst and a Soviet film (1957) directed by Grigori Kozintzev; a ballet (1965) by George Balanchine; and an American musical, Man of La Mancha (1965), by Mitch Leigh.

Its influence can be seen in the work of Smollett, Defoe, Fielding, and Sterne, as well as in the classic 19th-century novelists Scott, Dickens, Flaubert, Melville, and Dostoyevsky, and in the works of James Joyce and Jorge Luis Borges.The theme also inspired the 19th-century French artists Honoré Daumier and Gustave Doré.

Ethnic and Religious Heritage

Though most Cervantes scholars regard Cervantes of Spanish blood as far as his geneaology could be analyzed, some researchers suggest possible Basque and Portuguese origins.

His religious background is a more contested issue. Cervantes has been declared an Old Christian (pure blood), New Christian (converso), secularist, and Christian humanist. The two most thoroughly researched of which being Old Christian and New Christian. Purporters of the New Christian theory, established by Americo Castro, often suggest it to be on Cervantes' mother's side. The theory is almost exclusively supported by circumstantial evidence but would "explain" some mysteries of Cervantes' life.[19] The theory has been supported by authors such as Anthony Cascardi and Caravaggio. Others reject it strongly such as Claudio Albornoz or Francisco Olmos Garcia, who considers it a "tired issue" only supported by Americo Castro.[20]

The second origin theory suggests Cervantes is of Old Christian stock. Most of the evidence for this is supported by documentary evidence but does not help fill the gaps of some personality and life aspects of Cervantes as the New Christian theory does. In particular the only surviving document addressing Cervantes pedigree is the 1569 "Informacion de la limpieza de Miguel de Cervantes, estante en Roma" which addresses Cervantes directly as an Old Christian.[21] The full story of Cervantes' background will obviously never be known.

Criticism Bibliography

Cervantes' Don Quixote: A Reference Guide / Mancing, Howard., 2006 The humble story of Don Quixote: reflections on the birth of the modern novel / Bandera, Cesáreo., 2006

Notes

a. ^ The most reliable and accurate portrait of the writer to date is that provided by Cervantes himself in the Exemplary Novels (translated by Walter K. Kelly):[22]

This person whom you see here, with an oval visage, chestnut hair, smooth open forehead, lively eyes, a hooked but well-proportioned nose, and silvery beard that twenty years ago was golden, large moustaches, a small mouth, teeth not much to speak of, for he has but six, in bad condition and worse placed, no two of them corresponding to each other, a figure midway between the two extremes, neither tall nor short, a vivid complexion, rather fair than dark, somewhat stooped in the shoulders, and not very lightfooted: this, I say, is the author of Galatea, Don Quixote de la Mancha, The Journey to Parnassus, which he wrote in imitation of Cesare Caporali Perusino, and other works which are current among the public, and perhaps without the author's name. He is commonly called MIGUEL DE CERVANTES SAAVEDRA.

— Miguel de Cervantes, Exemplary Novels (Author's Preface)

b. ^ His signature spells Cerbantes with a b but he is now known after the spelling Cervantes used by the printers of his works. Saavedra was the surname of a distant relative that Cervantes adopted as his second surname after his return from Barbary Coast.[23] The earliest documents signed with Cervantes' two names (Cervantes Saavedra) appear several years after his repatriation. Cervantes began adding the second surname Saavedra (a name that did not correspond to his immediate family) to his patronymic in 1586-1587, in official documents related to his marriage to Catalina de Salazar.[24]

c. ^ The only evidence is a statement by Professor Tomas González, that he once saw an old entry of the matriculation of a Miguel de Cervantes.[25] No subsequent scholar has been successful in verifying this statement. In any case, there were at least two other Miguels born about the middle of the century.[6]

d. ^ "He" refers to the writer of a spurious Part II of Don Quixote (Second Volume of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha) known under the pseudonym Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda. Avellaneda had referred to Cervantes as an "old and one-handed" man.[7]

Citations

- ^ a b c "Cervantes, Miguel de". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2002.

- ^ Fuentes, Carlos. Myself with Others: Selected Essays. (1988).

- ^ William Byron, "Cervantes. A Biography," Doubleday& Company: Garden City, NY, 1978, pp. 23-32.

- ^ J. Canavaggio, Miguel de Cervantes

- ^ "Cervantes, Miguel de". The Encyclopedia Americana. 1994.

- ^ a b J. Ormsby, About Cervantes and Don Quixote

- ^ a b c C. Qualia, Cervantes, Soldier and Humanist, 1

- ^ E. Lokos, The Enigma of Cervantine Genealogy, 118

- ^ F.A. de Armas, Cervantes and the Italian Renaissance, 32

* F.A. de Armas, Quixotic Frescoes, 5 - ^ F.A. de Armas, Cervantes and the Italian Renaissance, 33

- ^ J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly, The Life of Cervantes, 9

- ^ M.A. Garcés, Cervantes in Algiers, 220

- ^ J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly, The Life of Cervantes, 41

- ^ M.A. Garcés, Cervantes in Algiers, 236

- ^ C. Calvo, Shakespeare and Cervantes in 1916, 78.

- ^ World Book and Copyright Day — April 23, 2006, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

- ^ The Spanish title of novela is misleading. In modern Spanish it means "novel", but Cervantes used it meaning the Italian shorter novellas.

- ^ Francis Carr, Who Wrote Don Quixote? (London: Xlibris Corporation, 2004).

- ^ Cervantes: A Biography by William Byron, Pg 32

- ^ Cervantes and His Postmodern Constituencies by Anne J. Cruz, Carroll B. Johnson, Pg 116

- ^ Cervantes and His Postmodern Constituencies by Anne J. Cruz, Carroll B. Johnson, Pg 117

- ^ M. de Cervantes, The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Exemplary Novels of Cervantes

- ^ M.A. Garcés, Cervantes in Algiers, 191-192

* C. Slade, Introduction, xxiv - ^ M.A. Garcés, Cervantes in Algiers, 191-192

- ^ J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly, The Life of Cervantes, 9

* J. Ormsby, About Cervantes and Don Quixote

References

Printed sources

- Armas, Frederick A. de (2002). "Cervantes and the Italian Renaissance". The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes By Anthony Joseph Cascardi. Cambridge University. ISBN 0-521-66387-3.

- Armas, Frederick A. de (2006). "The Exhilaration of Italy". Quixotic Frescoes: Cervantes and Italian Renaissance Art. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-802-09074-5.

- "Cervantes, Miguel de". The Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Incorporated. 1994.

- "Cervantes, Miguel de". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2002.

- Calvo, Clara (2004). "Shakespeare and Cervantes in 1916: The Politics of Language". Shifting the Scene: Shakespeare in European Culture By Ladina Bezzola Lambert, Balz Engler. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-874-13860-4.

- Fitzmaurice-Kelly, James (2005). "The Youth of Cervantes". The Life of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-417-97000-6.

- Garcés, María Antonia (2002). "An Erotics of Creation". Cervantes in Algiers: a Captive's Tale. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-826-51470-7.

- Lokos, Ellen (1998). "The Politics of Identity and the Enigma of Cervantine Genealogy". Cervantes and his Postomodern Consituencies by Ann J. Cruz. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-815-33206-8.

- Qualia, Charles B. (Januar 1949). "Cervantes, Soldier and Humanist". The South Central Bulletin. 9 (No.1). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 1+10-11.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Slade, Carole (2004). "Introduction". Don Quixote. Spark Publishing/SparkNotes. ISBN 1-59308-046-8.

Online sources

- Canavaggio, Jean. "Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616): Life and Portrait". The Cervantes Project. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de. "E-book of The Exemplary Novels of Cervantes (Translated by Walter K. Kelly)". The Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- Ormsby, John. "Don Quixote - Translator's Preface - About Cervantes And Don Quixote". The University of Adelaide Library. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- "World Book and Copyright Day - [[April 23]], [[2006]]". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved 2006-10-17.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help)

External links

- Works by Miguel de Cervantes at Project Gutenberg

- Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes Spanish web site with multiple Cervantes links and audio of whole of Don Quixote

- Famous Hispanics

- The Cervantes Project with biographies and chronology

- Entry in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica

- Relevant information about Miguel de Cervantes

- Life and times before writing Don Quixote

- Cervantes chapter from Spanish Literature by H. Butler Clarke 1893

This page or section may contain link spam masquerading as content. |