British Isles: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

The term ''British Isles'' is [[British Isles naming dispute|controversial]] in relation to Ireland,<ref name="ReferenceB"/><ref name="Myers"> [http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2000/0309/archive.00030900085.html An Irishman's Diary] Myers, Kevin; The [[Irish Times]] (subscription needed) 09/03/2000, Accessed July 2006 "millions of people from these islands - oh how angry we get when people call them the British Isles".</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=rasBRQwwOIIC&pg=PA7 Social work in the British Isles by Malcolm Payne, Steven Shardlow] When we think about social work in the British Isles, a contentious term if ever there was one, what do we expect to see?</ref> where there are objections to its usage due to the association of the word "British" with Ireland. The [[Government of Ireland]] discourages its use,<ref>[http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article658099.ece ''The Times'': "New atlas lets Ireland slip shackles of Britain".]</ref><ref>"[http://www.oireachtas-debates.gov.ie/D/0606/D.0606.200509280360.html Written Answers - Official Terms"], [[Dáil Éireann]] - Volume 606 - 28 September, 2005. In his response, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs stated that "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term. Our officials in the Embassy of Ireland, London, continue to monitor the media in Britain for any abuse of the official terms as set out in the Constitution of Ireland and in legislation. These include the name of the State, the President, [[Taoiseach]] and others."</ref> and in relations with the United Kingdom the words "these islands" are used.<ref> [http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/index.asp?locID=558&docID=3427 Bertie Ahern's Address to the Joint Houses of Parliament], Westminster, 15 May 2007</ref><ref> [http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/blair.htm Tony Blair's Address to the Dáil and Seanad], November 1998 </ref> Although still used as a geographic term, the controversy means that [[British Isles naming dispute#Alternative_terms|alternative terms]] such as '''"[[Britain and Ireland]]"''' are increasingly preferred.<ref>British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945-1999, Alistair Davies & Alan Sinfield, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0415128110, Page 9.</ref><ref>The Reformation in Britain and Ireland: An Introduction, Ian Hazlett, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0567082806, Chapter 2</ref> |

The term ''British Isles'' is [[British Isles naming dispute|controversial]] in relation to Ireland,<ref name="ReferenceB"/><ref name="Myers"> [http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2000/0309/archive.00030900085.html An Irishman's Diary] Myers, Kevin; The [[Irish Times]] (subscription needed) 09/03/2000, Accessed July 2006 "millions of people from these islands - oh how angry we get when people call them the British Isles".</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=rasBRQwwOIIC&pg=PA7 Social work in the British Isles by Malcolm Payne, Steven Shardlow] When we think about social work in the British Isles, a contentious term if ever there was one, what do we expect to see?</ref> where there are objections to its usage due to the association of the word "British" with Ireland. The [[Government of Ireland]] discourages its use,<ref>[http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article658099.ece ''The Times'': "New atlas lets Ireland slip shackles of Britain".]</ref><ref>"[http://www.oireachtas-debates.gov.ie/D/0606/D.0606.200509280360.html Written Answers - Official Terms"], [[Dáil Éireann]] - Volume 606 - 28 September, 2005. In his response, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs stated that "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term. Our officials in the Embassy of Ireland, London, continue to monitor the media in Britain for any abuse of the official terms as set out in the Constitution of Ireland and in legislation. These include the name of the State, the President, [[Taoiseach]] and others."</ref> and in relations with the United Kingdom the words "these islands" are used.<ref> [http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/index.asp?locID=558&docID=3427 Bertie Ahern's Address to the Joint Houses of Parliament], Westminster, 15 May 2007</ref><ref> [http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/blair.htm Tony Blair's Address to the Dáil and Seanad], November 1998 </ref> Although still used as a geographic term, the controversy means that [[British Isles naming dispute#Alternative_terms|alternative terms]] such as '''"[[Britain and Ireland]]"''' are increasingly preferred.<ref>British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945-1999, Alistair Davies & Alan Sinfield, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0415128110, Page 9.</ref><ref>The Reformation in Britain and Ireland: An Introduction, Ian Hazlett, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0567082806, Chapter 2</ref> |

||

==Etymology= |

==Etymology=WHERE IS MY COOKIE?!?! |

||

{{Main|Terminology of the British Isles|Britain (name)}} |

{{Main|Terminology of the British Isles|Britain (name)}} |

||

Revision as of 22:32, 19 January 2010

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Western Europe |

| Administration | |

Guernsey | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | ~65 million |

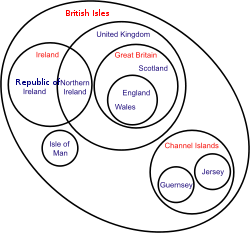

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include Great Britain, Ireland and over six-thousand smaller islands.[7] There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and Ireland.[8] The British Isles also include the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man and, by tradition, the Channel Islands, although the latter are not physically a part of the island group.[9][10]

The term British Isles is controversial in relation to Ireland,[7][11][12] where there are objections to its usage due to the association of the word "British" with Ireland. The Government of Ireland discourages its use,[13][14] and in relations with the United Kingdom the words "these islands" are used.[15][16] Although still used as a geographic term, the controversy means that alternative terms such as "Britain and Ireland" are increasingly preferred.[17][18]

==Etymology=WHERE IS MY COOKIE?!?!

The first references to the islands as a group appeared in the writings of travellers from the ancient Greek colony of Massalia.[19][20] These writings have been lost, but later writers quoted from the Massaliote Periplus (sixth century BC) and from Pytheas' On the Ocean (circa 325–320 BC),[21] providing several variations referring to the geographical area of the British Isles, including Britain and Ireland, which have survived. In the 1st century BC Diodorus introduced the Latin form Πρεττανια (Prettania) from Πρεττανικη (Prettanike)[20], Strabo (1.4.2) has Βρεττανία (Brettania) and Marcian of Heraclea in his Periplus maris exteri describes αἱ Πρεττανικαὶ νῆσοι (the Prettanic Isles). The historian Norman Davies states that "though the details are debatable, the main derivations looks pretty solid".[22] They believe that the peoples of these islands of Pretanike were called the Πρεττανοι (Priteni or Pretani), [20][23] names derived from a Celtic term which probably reached travellers like Pytheas from the Gauls, who may have used it as their name for the inhabitants of the islands.[19]

The replacement of the "P" of "Pretannia" to the "B" of Britannia by the Romans occurred during the time of Julius Caesar.[24] In classical Latin the plural term Britannicae insulae was sometimes used.[25]

The earliest citation of the phrase "Brytish Iles" in the Oxford English Dictionary[26] is dated 1577 in a work by John Dee.

In modern Welsh, the term Prydain ac Iwerddon ("Britain and Ireland") is common.[citation needed] Ynysoedd Prydain ("British Isles") usually refers to the territories of England, Scotland and Wales: it does not include Ireland, north or south.[27]

Alternative names and descriptions

Several different names are currently used to describe the islands. Dictionaries, encyclopaedias and atlases that use the term British Isles define it as Great Britain and Ireland and adjacent islands – typically including the Isle of Man, the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland.[28] Some definitions include the Channel Islands.[29] Commonly used alternative names[dubious ] are British-Irish Isles,[30] Britain and Ireland, Great Britain and Ireland, British Isles and Ireland,[31] or UK and Ireland.

UK media organisations such as the The Times and the BBC have style-guide entries to try to maintain consistent usage.[32][33] Encyclopædia Britannica, the Oxford University Press (publishers of the Oxford English Dictionary) and the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (publisher of Admiralty charts) have all occasionally used the term British Isles and Ireland.[34][35][36] The Economic History Society style guide suggests that use of the term British Isles should be avoided.[37]

Some international publications no longer use the term British Isles. In early 2008, it was reported that National Geographic said it would use the wording British and Irish Isles instead of British Isles.[38] In 2006, Folens, an Irish publisher of school text books, decided to stop using the term in Ireland while continuing to use it in the United Kingdom.[39][40] Since 2001 the rugby union team the British Isles or British Lions are now named the British and Irish Lions.

Geography

There are about 136 permanently inhabited islands in the group, the largest two being Great Britain and Ireland. Great Britain is to the east and covers 216,777 km2 (83,698 square miles), over half of the total landmass of the group. Ireland is to the west and covers 84,406 km2 (32,589 square miles). The largest of the other islands are to be found in the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland to the north, Anglesey and the Isle of Man between Great Britain and Ireland, and the Channel Islands near the coast of France.

The islands are at relatively low altitudes, with central Ireland and southern Great Britain particularly low lying: the lowest point in the islands is the Fens at −4 m (−13 ft). The Scottish Highlands in the northern part of Great Britain are mountainous, with Ben Nevis being the highest point in the British Isles at 1,344 m (4,409 ft) (4,409 ft). Other mountainous areas include Wales and parts of the island of Ireland, but only seven peaks in these areas reach above 1,000 m (3,281 ft) (3,281 ft). Lakes on the islands are generally not large, although Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland is an exception, covering 381 km2 (147 square miles); the largest freshwater body in Great Britain is Loch Lomond at 71.1 kilometres (44 mi). There are a number of major rivers within the British Isles. The river Severn at 354 km (220 mi) is the longest in Great Britain and the Shannon at 386 km (240 mi) is the longest in Ireland.

The British Isles have a temperate marine climate, the North Atlantic Drift ("Gulf Stream") which flows from the Gulf of Mexico brings with it significant moisture and raises temperatures 11 °C (20 °F) above the global average for the islands' latitudes.[41] Winters are thus warm and wet, with summers mild and also wet. Most Atlantic depressions pass to the north of the islands, combined with the general westerly circulation and interactions with the landmass, this imposes an east-west variation in climate.[42]

Geology

The British Isles lie at the juncture of several regions with past episodes of tectonic mountain building. These orogenic belts form a complex geology which records a huge and varied span of earth history.[43] Of particular note was the Caledonian Orogeny during the Ordovician Period, ca. 488–444 Ma and early Silurian period, when the craton Baltica collided with the terrane Avalonia to form the mountains and hills in northern Britain and Ireland. Baltica formed roughly the north western half of Ireland and Scotland. Further collisions caused the Variscan orogeny in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, forming the hills of Munster, south-west England, and south Wales. Over the last 500 million years the land which forms the islands has drifted northwest from around 30°S, crossing the equator around 370 million years ago to reach its present northern latitude.[44]

The islands have been shaped by numerous glaciations during the Quaternary Period, the most recent being the Devensian. As this ended, the central Irish Sea was de-glaciated (whether or not there was a land bridge between Great Britain and Ireland at this time is somewhat disputed, though there was certainly a single ice sheet covering the entire sea) and the English Channel flooded, with sea levels rising to current levels some 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, leaving the British Isles in their current form.

The islands' geology is highly complex, though there are large numbers of limestone and chalk rocks that formed in the Permian and Triassic periods. The west coasts of Ireland and northern Great Britain that directly face the Atlantic Ocean are generally characterized by long peninsulas, and headlands and bays; the internal and eastern coasts are "smoother".

Transport

Heathrow is Europe's busiest airport in terms of passenger traffic and the Dublin-London route is the busiest air route in Europe.[45] The English Channel and the southern North Sea are the busiest seaways in the world.[46] The Channel Tunnel, opened in 1994, links Great Britain to France and is the second-longest rail tunnel in the world. The idea of building a tunnel under the Irish Sea has been raised since 1895,[47] when it was first investigated. Several potential Irish Sea tunnel projects have been proposed, most recently the Tusker Tunnel between the ports of Rosslare and Fishguard proposed by The Institute of Engineers of Ireland in 2004.[48][49] A rail tunnel was proposed in 1997 on a different route, between Dublin and Holyhead, by British engineering firm Symonds. Either tunnel, at 80 km (50 mi), would be by far the longest in the world, and would cost an estimated €20 billion. A proposal in 2007,[50] estimated the cost of building a bridge from County Antrim in Northern Ireland to Galloway in Scotland at £3.5bn (€5bn).

Demographics

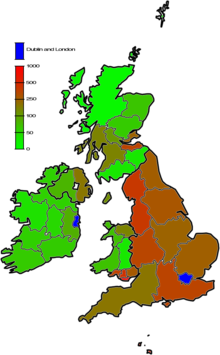

The demographics of the British Isles shows a generally high density of population in England, which accounts for almost 80% of the total population of the islands. In Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales high density of population is limited to areas around, or close to, their respective capitals. Major population centres (greater than one million people) exist in the following areas:

- Greater London Urban Area (8.5 million)

- London metropolitan area (12—14 million)

- Greater Manchester Urban Area (2.5 million)

- West Midlands conurbation (2.3 million)

- West Yorkshire Urban Area (2.1 million)

- Hampshire (1.7 million)

- Greater Glasgow (1.7 million)

- Greater Dublin Area (1.6 million)

- Lancashire (1.4 million)

- South Yorkshire (1.2 million)

- Tyne and Wear (1.1 million)

The population of England has risen steadily throughout its history, while the populations of Scotland and Wales have shown little increase during the twentieth century - the population of Scotland remaining unchanged since 1951. Ireland, which for most of its history comprised a population proportionate to its land area (one third of the total population) has, since the Great Famine, fallen to less than one tenth of the population of the British Isles. The famine, which caused a century-long population decline, drastically reduced the Irish population and permanently altered the demographic make-up of the British Isles. On a global scale this disaster led to the creation of an Irish diaspora that numbers fifteen times the current population of the island

| Ireland | British Isles | % of total | Graph | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 8.2 | 26.7 | 30.7% | File:IrePop1500.PNG |

| 1851 | 6.9 | 27.7 | 24.8% | |

| 1891 | 4.7 | 37.8 | 12.4% | |

| 1951 | 4.1 | 53.2 | 7.7% | |

| 1991 | 5.5 | 62.9 | 8.7% | |

| 2006 | 6.0 | 64.3 | 9.3% |

Political co-operation within the islands

Between 1801 and 1922, Great Britain and Ireland together formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[51] In 1922, twenty-six counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom following the Irish War of Independence and the Anglo-Irish Treaty; the remaining six counties, mainly in the northeast of the island, became known as Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act, 1920. Both states, but not the Isle of Man or the Channel Islands, are members of the European Union.

However, political cooperation between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland exists on some levels:

- Travel. Since Irish partition an informal free-travel area has continued to exist across the entire region; in 1997 it was formally recognised by the European Union, in the Amsterdam Treaty, as the Common Travel Area.

- Voting rights. No part of the British Isles considers a citizen of any other part as an 'alien'.[52] This pre-dates and goes much further than that required by European Union law, and gives common voting rights to all citizens of the jurisdictions within the archipelago. Exceptions to this are presidential elections and referendums in the Republic of Ireland, for which there is no comparable franchise in the other states. Other EU nationals may only vote in local and European Parliament elections while resident in either the UK or Ireland. A 2008 UK Ministry of Justice report proposed to end this arrangement arguing that, "the right to vote is one of the hallmarks of the political status of citizens; it is not a means of expressing closeness between countries."[53]

- Diplomatic. Bilateral agreements allow UK embassies to act as an Irish consulate when Ireland is not represented in a particular country.

- Northern Ireland. Citizens of Northern Ireland are entitled to the choice of Irish or British citizenship or both.

- The British-Irish Council was set up in 1999 following the 1998 Belfast Agreement. This body is made up of all political entities across the islands, both the sovereign governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom, the devolved governments of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and the dependencies of Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man. It has no executive authority but meets biannually to discuss issues of mutual importance, currently restricted to the misuse of drugs, the environment, the knowledge economy, social inclusion, tele-medicine, tourism, transport and national languages of the participants. During the February 2008 meeting of the Council, it was agreed to set-up a standing secretariat that would serve as a permanent 'civil service' for the Council.[54]

- The British-Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body (Irish: Comhlacht Idir-Pharlaiminteach na Breataine agus na hÉireann) was established in 1990. Originally it comprised 25 members of the Oireachtas, the Irish parliament, and 25 members of the parliament of the United Kingdom, with the purpose of building mutual understanding between members of both legislature. Since then the role and scope of the body has been expanded with the addition of five representatives from the Scottish Parliament, five from the National Assembly for Wales and five from the Northern Ireland Assembly. One member is also taken from the States of Jersey, one from the States of Guernsey and one from the High Court of Tynwald (Isle of Man). With no executive powers, it may investigate and collect witness evidence from the public on matters of mutual concern to its members, these have in the past ranged from issues such as the delivery of health services to rural populations, to the Sellafield nuclear facility, to the mutual recognition of penalty points against drivers across the British Isles. Reports on its findings are presented to the governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Leading on from developments in the British-Irish Council, the chair of the Body, Niall Blaney, has suggested a name-change and that the body should shadow the British-Irish Council's work.[55]

History

Languages

A Euler diagram showing language branches, major languages and typically where they are spoken for modern languages in the British Isles.

The ethno-linguistic heritage of the British Isles is very rich in comparison to other areas of similar size, with twelve languages from six groups across four branches of the Indo-European family. The Insular Celtic languages of the Goidelic sub-group (Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic) and the Brythonic sub-group (Cornish, Welsh and Breton, spoken in north-western France) are the only remaining Celtic languages - their continental relations becoming extinct during the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries. The Norman languages of Guernésiais, Jèrriais and Sarkese are spoken in the Channel Islands, as is French. A cant, called Shelta, is a language spoken by Irish Travellers, often as a means to conceal meaning from those outside the group. However, English, sometimes in the form of Scots, is the dominant language, with few monoglots remaining in the other languages of the region. The Norn language appears to have become extinct in the 18th/19th century.

Until perhaps 1950 the use of languages other than English roughly coincided with the major ethno-cultural regions in the British Isles. As such, many of them, especially the Celtic languages, became intertwined with national movements in these areas, seeking either greater independence from the parliament of the United Kingdom, seated in England, or complete secession. The common history of these languages was one of sharp decline in the mid-19th century, prompted by centuries of economic deprivation and official policy to discourage their use in favour of English. However, since the mid-twentieth century there has been somewhat of a revival of interest in maintaining and using them. Celtic-language medium schools are available throughout Ireland, Scotland and Wales to such an extent that it is now possible to receive all formal education, up to and including third-level education, through a Celtic language. Instruction in Irish and Welsh is compulsory in all schools in the Republic of Ireland and Wales respectively. In the Isle of Man, Manx in taught in all schools, although it is not compulsory, and there is one Manx-medium school. The respective languages are official languages of state in Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Wales, with equal status with respect to English. In the Channel Islands French is a legislative and administrative language (see Jersey Legal French). Since 2007, Irish is a working language of the European Union.

During the last 60 years there has been a great deal of immigration into Great Britain (less into Ireland). As a result a number of languages not formerly found in the British Isles are in regular use. Polish, Punjabi, and Hindustani (inc Urdu & Hindi), are each probably the first language of over 1 million residents, and a number of other languages are regularly spoken by substantial numbers of persons. Even in provincial areas it has become common for local government to publish information to residents in ten or so languages,[56] and in the largest city, London, the first language of about 20% of the population is neither English nor an indigenous Celtic language.[57] Cornish and the Norman languages of Guernésiais, Jèrriais and Sarkese are far less supported. In Jersey, a language office (L'Office du Jèrriais) is funded to provide education services for Jèrriais in schools and other language services, while in Guernsey there is a language officer and Guernésiais is taught in some schools on a volunteer basis. Of the four, only Cornish is recognised officially under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, and it is taught in some schools as an optional modern language. Guernésiais and Jèrriais are recognised as regional languages by the British and Irish governments within the framework of the British-Irish Council. Scots, as either a dialect of or a closely related language to English, is similarly recognised by the European Charter, the British-Irish Council, and as "part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland" under the Good Friday Agreement. However, it is without official status as a language of state in Scotland, where English is used in its place.

Shelta, spoken by the ethnic minority Irish Travellers, is thought to be spoken by 6,000–25,000 people, according to varying sources. Although evidence suggests that it existed as far back as the 13th century, as a secret language, it was only discovered at the end of the 19th century. It is without any official status, despite being thought to have 86,000 speakers worldwide, mostly in the USA.

Culture

Sport

A number of sports are popular throughout the British Isles, the most prominent of which is association football. While this is organised separately in different national associations, leagues and national teams, even within the UK, it is a common passion in all parts of the islands.

Rugby union is also widely enjoyed across the islands. The British and Irish Lions is a team made up of players from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales that undertakes tours of the southern hemisphere rugby playing nations every four years. This team was formerly known as the British Isles and the British Lions, but has been called the British and Irish Lions since 2001. Ireland play as a united team, represented by players from both Northern Ireland and the Republic. The four national rugby teams from Great Britain and Ireland play each other each year for the Triple Crown as part of the Six Nations Championship. Also since 2001 the professional club teams of Ireland, Scotland and Wales have competed together in the Magners League.

The Ryder Cup in golf was played between a United States team and a team representing Great Britain and Ireland. From 1979 onwards this was expanded to include the whole of Europe.

Popular culture

The United Kingdom and Ireland have separate media, although British television, newspapers and magazines are widely available in Ireland,[58] giving people in Ireland a high level of familiarity with cultural matters in Great Britain.

A few cultural events are organised for the island group as a whole. For example, the Costa Book Awards are awarded to authors resident in the UK or Ireland. The Man Booker Prize is awarded to authors from the Commonwealth of Nations or Ireland. The Mercury Music Prize is handed out every year to the best album from a British or Irish musician or group.

Many other bodies are organised throughout the islands as a whole; for example the Samaritans which is deliberately organised without regard to national boundaries on the basis that a service which is not political or religious should not recognise sectarian or political divisions.[59] The RNLI is also organised throughout the islands as a whole, covering both the United Kingdom and Ireland.[60]

See also

- Botanical Society of the British Isles

- Extreme points of the British Isles

- Great Britain and Ireland

References

- ^ Na hOileáin Bhriotanacha from CollinsHapper Pocket Irish Dictionary (ISBN 0-00-470765-6). Oileáin Iarthair Eorpa meaning Islands of Western Europe from Patrick S. Dineen, Foclóir Gaeilge Béarla, Irish-English Dictionary, Dublin, 1927. Éire agus an Bhreatain Mhór, meaning Ireland and Great Britain (from focail.ie, "The British Isles", Foras na Gaeilge, 2006)

- ^ Office of The President of Tynwald

- ^ University of Glasgow Department of Celtic. See paragraph "Dè dìreach a th’ ann an Ceiltis an Glaschu?" (Version in English. See para' "What is Celtic at Glasgow?")

- ^ Example:"Hunaniaethau Cenedlaethol Yn Nysoedd Prydain 1801-1914" (In English: "National Identities in the British Isles 1801-1914"). See also: Cardiff University Welsh-English Lexicon

- ^ National Statistics Office (2003). "Ethnic group statistics A guide for the collection and classification of ethnicity data" (PDF). HMSO.

- ^ For "Breetish" see Dictionary of the Scots Language (DSL) & Scottish National Dictionary Supplement (1976) (SNDS). For use in term "Breetish Isles" see Scots Language Centre website ("Show content as Scots").

- ^ a b "British Isles," Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ The diplomatic and constitutional name of the Irish state is simply Ireland. For disambiguation purposes "Republic of Ireland" is often used although technically not the name of the state but, according to the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, its "description". Article 4, Bunreacht na hÉireann. Section 2, Republic of Ireland Act, 1948.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "British Isles: a geographical term for the islands comparing Great Britain and Ireland with all their offshore islands including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands."

- ^ Alan, Lew; Colin, Hall; Dallen, Timothy (2008). World Geography of Travel and Tourism: A Regional Approach. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 9780750679787.

The British Isles comprise more than 6,000 islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe, including the countries of the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland. The group also includes the United Kingdom crown dependencies of the Isle of Man, and by tradition, the Channel Islands (the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey), even though these islands are strictly speaking an archipelago immediately off the coast of Normandy (France) rather than part of the British Isles.

- ^ An Irishman's Diary Myers, Kevin; The Irish Times (subscription needed) 09/03/2000, Accessed July 2006 "millions of people from these islands - oh how angry we get when people call them the British Isles".

- ^ Social work in the British Isles by Malcolm Payne, Steven Shardlow When we think about social work in the British Isles, a contentious term if ever there was one, what do we expect to see?

- ^ The Times: "New atlas lets Ireland slip shackles of Britain".

- ^ "Written Answers - Official Terms", Dáil Éireann - Volume 606 - 28 September, 2005. In his response, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs stated that "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term. Our officials in the Embassy of Ireland, London, continue to monitor the media in Britain for any abuse of the official terms as set out in the Constitution of Ireland and in legislation. These include the name of the State, the President, Taoiseach and others."

- ^ Bertie Ahern's Address to the Joint Houses of Parliament, Westminster, 15 May 2007

- ^ Tony Blair's Address to the Dáil and Seanad, November 1998

- ^ British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945-1999, Alistair Davies & Alan Sinfield, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0415128110, Page 9.

- ^ The Reformation in Britain and Ireland: An Introduction, Ian Hazlett, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0567082806, Chapter 2

- ^ a b Foster, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Allen, p. 172-174.

- ^ Harley, p. 150.

- ^ Davies, p. 47.

- ^ Snyder, p. 68.

- ^ Snyder, p. 12.

- ^ "Britain" Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ John Dee, 1577. 1577 J. Arte Navigation, p. 65 "The syncere Intent, and faythfull Aduise, of Georgius Gemistus Pletho, was, I could..frame and shape very much of Gemistus those his two Greek Orations..for our Brytish Iles, and in better and more allowable manner." From the OED, s.v. "British Isles"

- ^ Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru/University of Wales Dictionary, vol. 3, page 2916; vol. 4, p. 3819.

- ^ Longman Modern English Dictionary - "a group of islands off N.W. Europe comprising Great Britain Ireland, the Hebrides, Orkney the Shetland Is and adjacent islands"

Merriam Webster - "Function: geographical name, island group W Europe comprising Great Britain, Ireland, & adjacent islands"

dictionary.com - includes for example the American Heritage Dictionary - "British Isles, A group of islands off the northwest coast of Europe comprising Great Britain, Ireland, and adjacent smaller islands"

Encarta - "British Isles, group of islands in the northeastern Atlantic, separated from mainland Europe by the North Sea and the English Channel. It consists of the large islands of Great Britain and Ireland and almost 5,000 surrounding smaller islands and islets"

Philip's World Atlas

Times Atlas of the World

Insight Family World Atlas. Archived 2009-10-31. - ^ OED Online: "a geographical term for the islands comprising Great Britain and Ireland with all their offshore islands including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands"

GENUKI: Crown Dependencies

The British Isles and all that

Philips University Atlas - ^ John Oakland, 2003, British Civilization: A Student's Dictionary, Routledge: London

British-Irish Isles, the (geography) see BRITISH ISLES

British Isles, the (geography) A geographical (not political or CONSTITUTIONAL) term for ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, WALES, and IRELAND (including the REPUBLIC OF IRELAND), together with all offshore islands. A more accurate (and politically acceptable) term today is the British-Irish Isles.

- ^ Blackwellreference.com

- ^ Template:PDFlink "The British Isles is not a political entity. It is a geographical unit, the archipelago off the west coast of continental Europe covering Scotland, Wales, England, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands."

- ^ The Times: "Britain or Great Britain = England, Wales, Scotland and islands governed from the mainland (i.e. not Isle of Man or Channel Islands). United Kingdom = Great Britain and Northern Ireland. British Isles = United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, Isle of Man and Channel Islands. Do not confuse these entities."

- ^ Template:PDFlink Notice to Mariners of 2005 referring to a new edition of a nautical chart of the Western Approaches. Chart 2723 INT1605 International Chart Series, British Isles & Ireland, Western Approaches to the North Channel.

- ^ "Britannica.com Thus, the Gulf Stream–North Atlantic–Norway Current brings warm tropical waters northward, warming the climates of eastern North America, the British Isles and Ireland, and the Atlantic coast of Norway in winter, and the Kuroshio–North Pacific Current does the same for Japan and western North America, where warmer winter climates also occur. Page retrieved Feb eighteenth 2007.

- ^ "OUP.com The description of the OUP textbook "The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries" in the series on the history of the British Isles carries the description that it 'Offers an integrated geographical coverage of the whole of the British Isles and Ireland - rather than purely English history'" The same blurb goes on to say that the "book encompasses the histories of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and also considers the relationships between the different parts of the British Isles". Page retrieved Feb eighteenth 2007.

- ^ Economic History Society Style Guide

- ^ Tribune.ie, 'British Isles' references leave Irish eyes frowning, The Sunday Tribune, 27 January 2008

- ^ The Irish Times, "Folens to wipe 'British Isles' off the map in new atlas", 2 October 2006

- ^ British Isles is removed from school atlases

- ^ Mayes, Julian (1997). Regional Climates of the British Isles. London: Routledge. p. 13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ibid., pp. 13–14.

- ^ Goudie, Andrew S. (1994). The Environment of the British Isles, an Atlas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ibid., p. 5.

- ^ Seán McCárthaigh, Dublin–London busiest air traffic route within EU Irish Examiner, 31 March 2003

- ^ Thenail, Bruno. "EMDI - Espace Manche Development Initiative". European Community INTERREG IIIB NWE Programme. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "Tunnel under the Sea", The Washington Post, 2 May 1897 (Archive link)

- ^ A Vision of Transport in Ireland in 2050, IEI report (pdf), The Irish Academy of Engineers, 21/12/2004

- ^ Tunnel 'vision' under Irish Sea, (link), BBC news, Thursday, 23 December 2004

- ^ BBC News, From Twinbrook to the Trevi Fountain, 21 August 2007

- ^ Though the Irish Free State left the United Kingdom on 6 December 1922 the name of the United Kingdom was not changed to reflect that until April 1927, when Northern Ireland was substituted for Ireland in its name.

- ^ Who can vote, UK Electoral Commission, retrieved August 12, 2009.

- ^ Goldsmith, 2008, Citizenship: Our Common Bond, Ministry of Justice: London

- ^ [Communiqué of the British-Irish Council], February 2008

- ^ Martina Purdy, 28 February 2008 2008, Unionists urged to drop boycott, BBC: London

- ^ "Bristol City Council: Translating and interpreting services: Translations / Community language documents". Bristol.gov.uk. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ ‘A Profile of Londoners by Language’: Greater London Authority: Data Management and Analysis Group http://www.london.gov.uk/gla/publications/factsandfigures/dmag-briefing-2006-26.pdf

- ^ "Ireland". Museum.tv. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ Samaritans - Would you like to know more? > History > National growth

- ^ RNLI.org.uk, The RNLI is a charity that provides a 24-hour lifesaving service around the UK and Republic of Ireland.

Further reading

- Allen, Stephen (2007). Lords of Battle: The World of the Celtic Warrior. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841769487.

- Collingwood, Robin George (1998). Roman Britain and the English Settlements. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN 0819611603.

- Davies, Norman (2000). The Isles a History. Macmillan. ISBN 0333692837.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - Foster (editor), Robert Fitzroy (1 November 2001). The Oxford History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280202-X.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Harley, John Brian (1987). The History of Cartography: Cartography in prehistoric, ancient, and medieval Europe and the Mediterranean. Humana Press. ISBN 0226316335.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Markale, Jean (1994). King of the Celts. Bear & Company. ISBN 0892814527.

- Snyder, Christopher (2003). The Britons. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World, 3500 B.C. - 1603 A.D. by Simon Schama, BBC/Miramax, 2000 ISBN 978-0786866755

- A History of Britain — The Complete Collection on DVD by Simon Schama, BBC 2002

- Shortened History of England by G. M. Trevelyan Penguin Books ISBN 978-0140233230

External links

- 54°N 4°W / 54°N 4°W Geo Links for British Isles

- An interactive geological map of the British Isles.

- Geograph British Isles — Creative Commons-licensed, geo-located photographs of the British Isles.

- Britannicarum Insularum Typus, Ortelius 1624