Nixon shock: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

By December 1971, the import surcharge was dropped, as part of a general revaluation of the major currencies, which thereafter were allowed 2.25% devaluations from the agreed exchange rate. By March 1976, the world’s major currencies were floating — in other words, the currency exchange rates no longer were governments' principal means of administering [[monetary policy]]. |

By December 1971, the import surcharge was dropped, as part of a general revaluation of the major currencies, which thereafter were allowed 2.25% devaluations from the agreed exchange rate. By March 1976, the world’s major currencies were floating — in other words, the currency exchange rates no longer were governments' principal means of administering [[monetary policy]]. |

||

Analysts of the post-2007 financial crisis, such as David McNally (2009)<ref>McNally, David. 2009. “From financial crisis to world-slump: accumulation, financialisation, and the global slowdown.” Historical Materialism 17: 35-83.</ref> cite the end of the Bretton Woods dollar-gold convertibility as the modern source of monetary volatility, and consequent unregulated financialization. That volatility necessitated the rise of risk-hedging financial instruments, such as derivatives (including Credit Default Swaps). Thus as the value of the dollar was no longer based on gold, it became based instead on projected future value. The US economy and its firms become financialized (dependent on interest-paying financial transactions) to accommodate and take advantage of the risk inherent in the future value of the dollar as the basis for present value. Further, financialized firms and investors gained profits from speculating on that risk. Especially after the 1997 East Asian overaccumulation crisis necessitated loosening credit in the US so that working-class Americans could prop up global demand, working-class debt was packaged by banks and hedge funds and sold to themselves (banks and hedge funds), as well as to pension funds, investors, and financialized corporations. During Alan Greenspan’s tenure as President of the Federal Reserve (1987-2005) alone, private and public debt in the US quadrupled to $43 trillion.<ref>McNally, David. 2009: 61.</ref> When the bubble burst in 2007, capital fled the US. Private capital flows were reduced by $1.1 trillion in the third quarter of 2007.<ref>McNally, David. 2009: 65.</ref> There remain continued problems with valuing assets in the US, especially given public and private debt, the unabated diminishment of American working class purchasing power, and ongoing military expenditure. 40 years after the Nixon Shock, analysts predict the rise of competition among currency blocs for greater conrol of financial markets and global monetary privileges.<ref>McNally, David. 2009: 77.</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 00:06, 12 December 2009

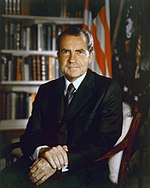

The Nixon Shock was a series of economic measures taken by U.S. President Richard Nixon in 1971 including unilaterally canceling the direct convertibility of the United States dollar to gold that essentially ended the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange.

Background

By the early 1970s, as the costs of the Vietnam War and increased domestic spending accelerated inflation,[1] the U.S. was running a balance of payments deficit and a trade deficit, the first in the 20th century. The year 1970 was the crucial turning point, which, because of foreign arbitrage of the U.S. dollar, caused governmental gold coverage of the paper dollar to decline 33 percentage points, from 55% to 22%. That, in the view of Neoclassical Economists and the Austrian School, represented the point where holders of the U.S. dollar lost faith in the U.S. government’s ability to cut its budget and trade deficits.

In 1971, the U.S. government again printed more dollars (a 10% increase)[1] and then sent them overseas, to pay for the nation's military spending and private investments. In the first six months of 1971, $22 billion dollars in assets left the U.S. [citation needed] In May 1971, inflation-wary West Germany was the first member country to leave the Bretton Woods system — unwilling to deflate the deutsche mark to prop up the dollar.[1] In order to prevent the dumping of the deutsche mark on the open market, West Germany did not consult with the international monetary community before making the change. In the next three months, West Germany’s move strengthened their economy; simultaneously, the dollar dropped 7.5% against the Deutsch mark.[1]

Because of the excess printed dollars, and the negative U.S. trade balance, other nations began demanding fulfillment of America’s “promise to pay” - that is, the redemption of their dollars for gold. Switzerland redeemed $50 million of paper for gold in July.[1] France, in particular, repeatedly made aggressive demands, and acquired $191 million in gold, further depleting the gold reserves of the U.S.[1] On 5 August 1971, Congress released a report recommending devaluation of the dollar, in an effort to protect the dollar against foreign price-gougers.[1] Still, on 9 August 1971, as the dollar dropped in value against European currencies, Switzerland withdrew the Swiss franc from the Bretton Woods system.[1]

The shock

To stabilize the economy and combat runaway inflation, on August 15, 1971, President Nixon imposed a 90-day wage and price freeze, a 10 percent import surcharge, and, most importantly, “closed the gold window”, ending convertibility between US dollars and gold. The President and fifteen advisors made that decision without consulting the members of the international monetary system, thus the international community informally named it the Nixon shock. Given the importance of the announcement — and its impact upon foreign currencies — presidential advisors recalled that they spent more time deciding when to publicly announce the controversial plan, than they spent creating the plan.[2] He was advised that the practical decision was to make an announcement before the stock markets opened on Monday (and just when Asian markets also were opening trading for the day). On August 15, 1971, that speech and the price-control plans proved very popular and raised the public's spirit. The President was credited with finally rescuing the American public from price-gougers, and from a foreign-caused exchange crisis. [2][3]

By December 1971, the import surcharge was dropped, as part of a general revaluation of the major currencies, which thereafter were allowed 2.25% devaluations from the agreed exchange rate. By March 1976, the world’s major currencies were floating — in other words, the currency exchange rates no longer were governments' principal means of administering monetary policy.

Analysts of the post-2007 financial crisis, such as David McNally (2009)[4] cite the end of the Bretton Woods dollar-gold convertibility as the modern source of monetary volatility, and consequent unregulated financialization. That volatility necessitated the rise of risk-hedging financial instruments, such as derivatives (including Credit Default Swaps). Thus as the value of the dollar was no longer based on gold, it became based instead on projected future value. The US economy and its firms become financialized (dependent on interest-paying financial transactions) to accommodate and take advantage of the risk inherent in the future value of the dollar as the basis for present value. Further, financialized firms and investors gained profits from speculating on that risk. Especially after the 1997 East Asian overaccumulation crisis necessitated loosening credit in the US so that working-class Americans could prop up global demand, working-class debt was packaged by banks and hedge funds and sold to themselves (banks and hedge funds), as well as to pension funds, investors, and financialized corporations. During Alan Greenspan’s tenure as President of the Federal Reserve (1987-2005) alone, private and public debt in the US quadrupled to $43 trillion.[5] When the bubble burst in 2007, capital fled the US. Private capital flows were reduced by $1.1 trillion in the third quarter of 2007.[6] There remain continued problems with valuing assets in the US, especially given public and private debt, the unabated diminishment of American working class purchasing power, and ongoing military expenditure. 40 years after the Nixon Shock, analysts predict the rise of competition among currency blocs for greater conrol of financial markets and global monetary privileges.[7]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 295–298. ISBN 0465041957.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Yergin, Daniel (1997). "Nixon Tries Price Controls". Commanding Heights. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hetzel, Robert L. (2008), p. 84

- ^ McNally, David. 2009. “From financial crisis to world-slump: accumulation, financialisation, and the global slowdown.” Historical Materialism 17: 35-83.

- ^ McNally, David. 2009: 61.

- ^ McNally, David. 2009: 65.

- ^ McNally, David. 2009: 77.