Future of an expanding universe: Difference between revisions

→Timeline: Move times out of section headings for brevity, following example of Timeline of the Big Bang and per WP:HEAD. Remove unnecessary articles from headings |

No this is the full version, we moved it from the Heat Death already. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

:''For the past, including the Primordial Era, see [[Timeline of the Big Bang]].'' |

:''For the past, including the Primordial Era, see [[Timeline of the Big Bang]].'' |

||

| ⚫ | |||

===Stelliferous Era=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{seealso|Graphical timeline of the Stelliferous Era}} |

{{seealso|Graphical timeline of the Stelliferous Era}} |

||

The universe is currently 13.7×10<sup>9</sup> (13.7 billion) years old.<ref name=wmap_5yr /> This time is in the Stelliferous Era. About 155 million years after the Big Bang, the first star formed. Since then, stars have formed by the collapse of small, dense core regions in large, cold [[molecular cloud]]s of [[hydrogen]] gas. At first, this produces a [[protostar]], which is hot and bright because of energy generated by [[gravitational contraction]]. After the protostar contracts for a while, its center will become hot enough to [[nuclear fusion|fuse]] hydrogen and its lifetime as a star will properly begin.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, pp. 35–39.</sup> |

The universe is currently 13.7×10<sup>9</sup> (13.7 billion) years old.<ref name=wmap_5yr /> This time is in the Stelliferous Era. About 155 million years after the Big Bang, the first star formed. Since then, stars have formed by the collapse of small, dense core regions in large, cold [[molecular cloud]]s of [[hydrogen]] gas. At first, this produces a [[protostar]], which is hot and bright because of energy generated by [[gravitational contraction]]. After the protostar contracts for a while, its center will become hot enough to [[nuclear fusion|fuse]] hydrogen and its lifetime as a star will properly begin.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, pp. 35–39.</sup> |

||

| Line 26: | Line 25: | ||

Stars whose mass is very low will eventually exhaust all their fusible [[hydrogen]] and then become [[helium]] [[white dwarf]]s.<ref name=endms>The End of the Main Sequence, Gregory Laughlin, Peter Bodenheimer, and Fred C. Adams, ''The Astrophysical Journal'', '''482''' ([[June 10]], [[1997]]), pp. 420–432. {{bibcode|1997ApJ...482..420L}}. {{doi|10.1086/304125}}.</ref> Stars of low to medium mass will expel some of their mass as a [[planetary nebula]] and eventually become a [[white dwarf]]; more massive stars will explode in a [[core-collapse supernova]], leaving behind [[neutron star]]s or [[stellar-mass black hole|black holes]].<ref name="evo">[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...591..288H How Massive Single Stars End Their Life], A. Heger, C. L. Fryer, S. E. Woosley, N. Langer, and D. H. Hartmann, ''Astrophysical Journal'' '''591''', #1 (2003), pp. 288–300.</ref> In any case, although some of the star's matter may be returned to the [[interstellar medium]], a [[compact star|degenerate remnant]] will be left behind whose mass is not returned to the interstellar medium. Therefore, the supply of gas available for [[star formation]] is steadily being exhausted. |

Stars whose mass is very low will eventually exhaust all their fusible [[hydrogen]] and then become [[helium]] [[white dwarf]]s.<ref name=endms>The End of the Main Sequence, Gregory Laughlin, Peter Bodenheimer, and Fred C. Adams, ''The Astrophysical Journal'', '''482''' ([[June 10]], [[1997]]), pp. 420–432. {{bibcode|1997ApJ...482..420L}}. {{doi|10.1086/304125}}.</ref> Stars of low to medium mass will expel some of their mass as a [[planetary nebula]] and eventually become a [[white dwarf]]; more massive stars will explode in a [[core-collapse supernova]], leaving behind [[neutron star]]s or [[stellar-mass black hole|black holes]].<ref name="evo">[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...591..288H How Massive Single Stars End Their Life], A. Heger, C. L. Fryer, S. E. Woosley, N. Langer, and D. H. Hartmann, ''Astrophysical Journal'' '''591''', #1 (2003), pp. 288–300.</ref> In any case, although some of the star's matter may be returned to the [[interstellar medium]], a [[compact star|degenerate remnant]] will be left behind whose mass is not returned to the interstellar medium. Therefore, the supply of gas available for [[star formation]] is steadily being exhausted. |

||

====Milky Way Galaxy and the Andromeda Galaxy merge into one==== |

====The Milky Way Galaxy and the Andromeda Galaxy merge into one galaxy: 3 billion years from now==== |

||

:''3 billion years from now (17 billion years after the Big Bang)'' |

|||

{{main|Andromeda-Milky Way collision}} |

{{main|Andromeda-Milky Way collision}} |

||

The [[Andromeda Galaxy]] is currently approximately 2.5 million light years away from our galaxy, the [[Milky Way Galaxy]], and the galaxies are moving towards each other at approximately 120 kilometers per second. Approximately three billion years from now, or 17 billion years after the Big Bang, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy may collide with one another and merge into one large galaxy. Because it is not known precisely how fast the Andromeda Galaxy is moving transverse to us, it is not certain that the collision will happen.<ref>[http://www.galaxydynamics.org/papers/GreatMilkyWayAndromedaCollision.pdf The Great Milky Way-Andromeda Collision], John Dubinski, ''Sky and Telescope'', October 2006. {{bibcode|2006S&T...112d..30D}}.</ref> |

The [[Andromeda Galaxy]] is currently approximately 2.5 million light years away from our galaxy, the [[Milky Way Galaxy]], and the galaxies are moving towards each other at approximately 120 kilometers per second. Approximately three billion years from now, or 17 billion years after the Big Bang, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy may collide with one another and merge into one large galaxy. Because it is not known precisely how fast the Andromeda Galaxy is moving transverse to us, it is not certain that the collision will happen.<ref>[http://www.galaxydynamics.org/papers/GreatMilkyWayAndromedaCollision.pdf The Great Milky Way-Andromeda Collision], John Dubinski, ''Sky and Telescope'', October 2006. {{bibcode|2006S&T...112d..30D}}.</ref> |

||

====Coalescence of Local Group==== |

====Coalescence of Local Group: 10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) to 10<sup>12</sup> (1 trillion) years from now==== |

||

:''10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) to 10<sup>12</sup> (1 trillion) years'' |

|||

The [[galaxies]] in the [[Local Group]], the cluster of galaxies which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, are gravitationally bound to each other. It is expected that between 10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) and 10<sup>12</sup> (1 trillion) years from now, their orbits will decay and the entire Local Group will merge into one large galaxy.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IIIA.</sup> |

The [[galaxies]] in the [[Local Group]], the cluster of galaxies which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, are gravitationally bound to each other. It is expected that between 10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) and 10<sup>12</sup> (1 trillion) years from now, their orbits will decay and the entire Local Group will merge into one large galaxy.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IIIA.</sup> |

||

====Galaxies outside the Local Supercluster are no longer detectable==== |

====Galaxies outside the Local Supercluster are no longer detectable: 2×10<sup>12</sup> (2 trillion) years from now==== |

||

:''2×10<sup>12</sup> (2 trillion) years'' |

|||

Assuming that [[dark energy]] continues to make the universe expand at an accelerating rate, 2×10<sup>12</sup> (2 trillion) years from now, all galaxies outside the [[Local Supercluster]] will be [[red-shift]]ed to such an extent that even [[gamma ray]]s they emit will have wavelengths longer than the size of the [[observable universe]] of the time. Therefore, these galaxies will no longer be detectable in any way.<ref name=lun>Life, the Universe, and Nothing: Life and Death in an Ever-expanding Universe, Lawrence M. Krauss and Glenn D. Starkman, ''Astrophysical Journal'', '''531''' ([[March 1]], [[2000]]), pp. 22–30. {{doi|10.1086/308434}}. {{bibcode|2000ApJ...531...22K}}.</ref> |

Assuming that [[dark energy]] continues to make the universe expand at an accelerating rate, 2×10<sup>12</sup> (2 trillion) years from now, all galaxies outside the [[Local Supercluster]] will be [[red-shift]]ed to such an extent that even [[gamma ray]]s they emit will have wavelengths longer than the size of the [[observable universe]] of the time. Therefore, these galaxies will no longer be detectable in any way.<ref name=lun>Life, the Universe, and Nothing: Life and Death in an Ever-expanding Universe, Lawrence M. Krauss and Glenn D. Starkman, ''Astrophysical Journal'', '''531''' ([[March 1]], [[2000]]), pp. 22–30. {{doi|10.1086/308434}}. {{bibcode|2000ApJ...531...22K}}.</ref> |

||

=== Degenerate Era=== |

=== The Degenerate Era, from 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) to 10<sup>40</sup> years from now=== |

||

:''From 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) to 10<sup>40</sup> years'' |

|||

By 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years from now, star formation will end, leaving all stellar objects in the form of [[compact star|degenerate remnants]]. This period, known as the Degenerate Era, will last until the degenerate remnants finally decay.<ref name=dying /><sup>, § III–IV.</sup> |

By 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years from now, star formation will end, leaving all stellar objects in the form of [[compact star|degenerate remnants]]. This period, known as the Degenerate Era, will last until the degenerate remnants finally decay.<ref name=dying /><sup>, § III–IV.</sup> |

||

====Star formation ceases==== |

====Star formation ceases: 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years==== |

||

:''10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years'' |

|||

It is estimated that in 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years or less, star formation will end.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IID.</sup> The least massive stars take the longest to exhaust their hydrogen fuel (see [[stellar evolution]]). Thus, the longest living stars in the universe are low-mass [[red dwarf]]s, with a mass of about 0.08 [[solar mass]]es, which have a lifetime of order 10<sup>13</sup> (10 trillion) years.<ref name=low_mass_lifetime>Adams & Laughlin (1997), §IIA and Figure 1.</ref> Coincidentally, this is comparable to the length of time over which star formation takes place.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IID.</sup> Once star formation ends and the least massive red dwarfs exhaust their fuel, [[nuclear fusion]] will cease. The low-mass red dwarfs will cool and become [[white dwarf]]s.<ref name=endms /> The only objects remaining with more than [[planemo|planetary mass]] will be [[brown dwarf]]s, with mass less than 0.08 solar masses, and [[compact star|degenerate remnants]]: [[white dwarf]]s, produced by stars with initial masses between about 0.08 and 8 solar masses, and [[neutron star]]s and [[stellar black hole|black hole]]s, produced by stars with initial masses over 8 solar masses. Most of the mass of this collection, approximately 90%, will be in the form of white dwarfs.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIE.</sup> In the absence of any energy source, all of these formerly [[luminous]] bodies will cool and become faint. |

It is estimated that in 10<sup>14</sup> (100 trillion) years or less, star formation will end.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IID.</sup> The least massive stars take the longest to exhaust their hydrogen fuel (see [[stellar evolution]]). Thus, the longest living stars in the universe are low-mass [[red dwarf]]s, with a mass of about 0.08 [[solar mass]]es, which have a lifetime of order 10<sup>13</sup> (10 trillion) years.<ref name=low_mass_lifetime>Adams & Laughlin (1997), §IIA and Figure 1.</ref> Coincidentally, this is comparable to the length of time over which star formation takes place.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IID.</sup> Once star formation ends and the least massive red dwarfs exhaust their fuel, [[nuclear fusion]] will cease. The low-mass red dwarfs will cool and become [[white dwarf]]s.<ref name=endms /> The only objects remaining with more than [[planemo|planetary mass]] will be [[brown dwarf]]s, with mass less than 0.08 solar masses, and [[compact star|degenerate remnants]]: [[white dwarf]]s, produced by stars with initial masses between about 0.08 and 8 solar masses, and [[neutron star]]s and [[stellar black hole|black hole]]s, produced by stars with initial masses over 8 solar masses. Most of the mass of this collection, approximately 90%, will be in the form of white dwarfs.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIE.</sup> In the absence of any energy source, all of these formerly [[luminous]] bodies will cool and become faint. |

||

The universe will become extremely dark after the last [[star]] burns out. Even so, there can still be occasional light in the universe. One of the ways the universe can be illuminated is if two [[carbon]]-[[oxygen]] white dwarfs with a combined mass of more than the [[Chandrasekhar limit]] of about 1.4 solar masses happen to merge. The resulting object will then undergo runaway thermonuclear fusion, producing a [[Type Ia supernova]] and dispelling the darkness of the Degenerate Era for a few weeks.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIIC;</sup><ref>[http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys240/lectures/future/future.html The Future of the Universe], Michael Richmond, lecture notes, Physics 240, [[Rochester Institute of Technology]]. Accessed on line [[July 8]], [[2008]].</ref> If the combined mass is not above the Chandrasekhar limit but is larger than the minimum mass to [[nuclear fusion|fuse]] carbon (about 0.9 solar masses), a [[carbon star]] could be produced, with a lifetime of around 10<sup>6</sup> (1 million) years.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, p. 91</sup> Also, if two [[helium]] white dwarfs with a combined mass of at least 0.3 solar masses collide, a [[helium star]] may be produced, with a lifetime of a few hundred million years.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, p. 91</sup> Finally, if brown dwarfs collide with each other, a [[red dwarf]] star may be produced which can survive for 10<sup>13</sup> (10 trillion) years.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIIC.</sup><ref name=low_mass_lifetime /> |

The universe will become extremely dark after the last [[star]] burns out. Even so, there can still be occasional light in the universe. One of the ways the universe can be illuminated is if two [[carbon]]-[[oxygen]] white dwarfs with a combined mass of more than the [[Chandrasekhar limit]] of about 1.4 solar masses happen to merge. The resulting object will then undergo runaway thermonuclear fusion, producing a [[Type Ia supernova]] and dispelling the darkness of the Degenerate Era for a few weeks.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIIC;</sup><ref>[http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys240/lectures/future/future.html The Future of the Universe], Michael Richmond, lecture notes, Physics 240, [[Rochester Institute of Technology]]. Accessed on line [[July 8]], [[2008]].</ref> If the combined mass is not above the Chandrasekhar limit but is larger than the minimum mass to [[nuclear fusion|fuse]] carbon (about 0.9 solar masses), a [[carbon star]] could be produced, with a lifetime of around 10<sup>6</sup> (1 million) years.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, p. 91</sup> Also, if two [[helium]] white dwarfs with a combined mass of at least 0.3 solar masses collide, a [[helium star]] may be produced, with a lifetime of a few hundred million years.<ref name=fiveages /><sup>, p. 91</sup> Finally, if brown dwarfs collide with each other, a [[red dwarf]] star may be produced which can survive for 10<sup>13</sup> (10 trillion) years.<ref name=dying /><sup> §IIIC.</sup><ref name=low_mass_lifetime /> |

||

==== Planets fall or are flung from orbits by a close encounter with another star==== |

==== Planets fall or are flung from orbits by a close encounter with another star: 10<sup>15</sup> years from now ==== |

||

:''10<sup>15</sup> years'' |

|||

Over time, the [[orbit]]s of planets will decay due to [[gravitational radiation]], or planets will be ejected from their local systems by [[gravitational perturbations]] caused by encounters with another [[compact star|stellar remnant]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IIIF, Table I.</sup> |

Over time, the [[orbit]]s of planets will decay due to [[gravitational radiation]], or planets will be ejected from their local systems by [[gravitational perturbations]] caused by encounters with another [[compact star|stellar remnant]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IIIF, Table I.</sup> |

||

====Stellar remnants escape galaxies or fall into black holes==== |

====Stellar remnants escape galaxies or fall into black holes: 10<sup>19</sup> to 10<sup>20</sup> years from now==== |

||

:''10<sup>19</sup> to 10<sup>20</sup> years'' |

|||

Over time, objects in a [[galaxy]] exchange [[kinetic energy]] in a process called [[dynamical relaxation]], making their velocity distribution approach the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]].<ref>p. 428, A deep focus on NGC 1883, A. L. Tadross, ''Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India'' '''33''', #4 (December 2005), pp. 421–431, {{bibcode|2005BASI...33..421T}}.</ref> Dynamical relaxation can proceed either by close encounters of two stars or by less violent but more frequent distant encounters.<ref>[http://webusers.astro.umn.edu/~llrw/a4002/SG_notes.txt Reading notes], Liliya L. R. Williams, Astrophysics II: Galactic and Extragalactic Astronomy, [[University of Minnesota]], accessed on line [[July 20]], [[2008]].</ref> In the case of a close encounter, two [[brown dwarfs]] or [[compact star|stellar remnants]] will pass close to each other. When this happens, the trajectories of the objects involved in the close encounter change slightly. After a large number of encounters, lighter objects tend to gain [[kinetic energy]] while the heavier objects lose it.<ref name=fiveages>''The Five Ages of the Universe'', Fred Adams and Greg Laughlin, New York: The Free Press, 1999, ISBN 0-684-85422-8.</ref><sup>, pp. 85–87</sup> |

Over time, objects in a [[galaxy]] exchange [[kinetic energy]] in a process called [[dynamical relaxation]], making their velocity distribution approach the [[Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution]].<ref>p. 428, A deep focus on NGC 1883, A. L. Tadross, ''Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India'' '''33''', #4 (December 2005), pp. 421–431, {{bibcode|2005BASI...33..421T}}.</ref> Dynamical relaxation can proceed either by close encounters of two stars or by less violent but more frequent distant encounters.<ref>[http://webusers.astro.umn.edu/~llrw/a4002/SG_notes.txt Reading notes], Liliya L. R. Williams, Astrophysics II: Galactic and Extragalactic Astronomy, [[University of Minnesota]], accessed on line [[July 20]], [[2008]].</ref> In the case of a close encounter, two [[brown dwarfs]] or [[compact star|stellar remnants]] will pass close to each other. When this happens, the trajectories of the objects involved in the close encounter change slightly. After a large number of encounters, lighter objects tend to gain [[kinetic energy]] while the heavier objects lose it.<ref name=fiveages>''The Five Ages of the Universe'', Fred Adams and Greg Laughlin, New York: The Free Press, 1999, ISBN 0-684-85422-8.</ref><sup>, pp. 85–87</sup> |

||

| Line 66: | Line 54: | ||

[[Image:BlackHole.jpg|thumb|right|245px|<center>The [[supermassive black hole]]s are all that remains of galaxies once all protons decay, but even these giants are not immortal.</center>]] |

[[Image:BlackHole.jpg|thumb|right|245px|<center>The [[supermassive black hole]]s are all that remains of galaxies once all protons decay, but even these giants are not immortal.</center>]] |

||

==== Nucleons start to decay==== |

==== Nucleons start to decay: >10<sup>32</sup> years ==== |

||

:''>10<sup>32</sup> years'' |

|||

The subsequent evolution of the universe depends on the existence and rate of [[proton decay]]. Experimental evidence shows that if the [[proton]] is unstable, it has a [[half-life]] of at least 10<sup>32</sup> years.<ref>[http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/decays.html Theory: Decays], SLAC Virtual Visitor Center. Accessed on line [[June 28]], [[2008]].</ref> If a [[Grand Unified Theory]] is correct, then there are theoretical reasons to believe that the half-life of the proton is under 10<sup>41</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVA.</sup> If not, the proton is still expected to decay, for example via processes involving [[virtual black holes]], with a half-life of under 10<sup>200</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVF</sup> [[Neutron]]s bound into [[atomic nucleus|nuclei]] are also expected to decay with a half-life comparable to the proton's.<ref name=dying>A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, ''Reviews of Modern Physics'' '''69''', #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. {{bibcode|1997RvMP...69..337A}}. {{doi|10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337}} {{arxiv|astro-ph|9701131}}.</ref><sup>, §IVA</sup> |

The subsequent evolution of the universe depends on the existence and rate of [[proton decay]]. Experimental evidence shows that if the [[proton]] is unstable, it has a [[half-life]] of at least 10<sup>32</sup> years.<ref>[http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/decays.html Theory: Decays], SLAC Virtual Visitor Center. Accessed on line [[June 28]], [[2008]].</ref> If a [[Grand Unified Theory]] is correct, then there are theoretical reasons to believe that the half-life of the proton is under 10<sup>41</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVA.</sup> If not, the proton is still expected to decay, for example via processes involving [[virtual black holes]], with a half-life of under 10<sup>200</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVF</sup> [[Neutron]]s bound into [[atomic nucleus|nuclei]] are also expected to decay with a half-life comparable to the proton's.<ref name=dying>A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, ''Reviews of Modern Physics'' '''69''', #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. {{bibcode|1997RvMP...69..337A}}. {{doi|10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337}} {{arxiv|astro-ph|9701131}}.</ref><sup>, §IVA</sup> |

||

| Line 75: | Line 61: | ||

The rest of this timeline assumes that the proton half-life is approximately 10<sup>37</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVA.</sup> Shorter or longer proton half-lives will accelerate or retard the process. This means that after 10<sup>37</sup> years, one-half of all baryonic matter will have been converted into [[gamma ray]] [[photon]]s and [[leptons]] through proton decay. |

The rest of this timeline assumes that the proton half-life is approximately 10<sup>37</sup> years.<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVA.</sup> Shorter or longer proton half-lives will accelerate or retard the process. This means that after 10<sup>37</sup> years, one-half of all baryonic matter will have been converted into [[gamma ray]] [[photon]]s and [[leptons]] through proton decay. |

||

==== All nucleons decay==== |

==== All nucleons decay: 10<sup>40</sup> years ==== |

||

:''10<sup>40</sup> years'' |

|||

Given our assumed half-life of the proton, [[nucleons]] (protons and bound neutrons) will have undergone roughly 1,000 half-lives by the time the universe is 10<sup>40</sup> years old. To put this into perspective, there are an estimated 10<sup>80</sup> protons currently in the universe.<ref>[http://www.nap.edu/html/oneuniverse/frontiers_solution_17.html Solution, exercise 17], ''One Universe: At Home in the Cosmos'', Neil de Grasse Tyson, Charles Tsun-Chu Liu, and Robert Irion, Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2000. ISBN 0-309-06488-0.</ref> This means that the number of nucleons will be slashed in half 1,000 times by the time the universe is 10<sup>40</sup> years old. Hence, there will be roughly ½<sup>1,000</sup> (approximately 10<sup>–301</sup>) as many nucleons remaining as there are today; that is, ''zero'' nucleons remaining in the universe at the end of the Degenerate Age. Effectively, all baryonic matter will have been changed into [[photons]] and leptons. |

Given our assumed half-life of the proton, [[nucleons]] (protons and bound neutrons) will have undergone roughly 1,000 half-lives by the time the universe is 10<sup>40</sup> years old. To put this into perspective, there are an estimated 10<sup>80</sup> protons currently in the universe.<ref>[http://www.nap.edu/html/oneuniverse/frontiers_solution_17.html Solution, exercise 17], ''One Universe: At Home in the Cosmos'', Neil de Grasse Tyson, Charles Tsun-Chu Liu, and Robert Irion, Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2000. ISBN 0-309-06488-0.</ref> This means that the number of nucleons will be slashed in half 1,000 times by the time the universe is 10<sup>40</sup> years old. Hence, there will be roughly ½<sup>1,000</sup> (approximately 10<sup>–301</sup>) as many nucleons remaining as there are today; that is, ''zero'' nucleons remaining in the universe at the end of the Degenerate Age. Effectively, all baryonic matter will have been changed into [[photons]] and leptons. |

||

=== Black Hole Era=== |

=== The Black Hole Era, from 10<sup>40</sup> years to 10<sup>100</sup> years from now=== |

||

:''10<sup>40</sup> years to 10<sup>100</sup> years'' |

|||

After 10<sup>40</sup> years, black holes will dominate the universe. They will slowly evaporate via [[Hawking radiation]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVG.</sup> A black hole with a mass of around 1 solar mass will vanish in around 2×10<sup>66</sup> years. As the lifetime of a black hole is proportional to the cube of its mass, more massive black holes take longer to decay. A supermassive black hole with a mass of 10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) solar masses will evaporate in around 2×10<sup>99</sup> years.<ref name=page>Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole, Don N. Page, ''Physical Review D'' '''13''' (1976), pp. 198–206. {{doi|10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198}}. See in particular equation (27).</ref> |

After 10<sup>40</sup> years, black holes will dominate the universe. They will slowly evaporate via [[Hawking radiation]].<ref name=dying /><sup>, §IVG.</sup> A black hole with a mass of around 1 solar mass will vanish in around 2×10<sup>66</sup> years. As the lifetime of a black hole is proportional to the cube of its mass, more massive black holes take longer to decay. A supermassive black hole with a mass of 10<sup>11</sup> (100 billion) solar masses will evaporate in around 2×10<sup>99</sup> years.<ref name=page>Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole, Don N. Page, ''Physical Review D'' '''13''' (1976), pp. 198–206. {{doi|10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198}}. See in particular equation (27).</ref> |

||

| Line 89: | Line 71: | ||

<span id="Dark Era" /> |

<span id="Dark Era" /> |

||

===Dark Era=== |

=== The Dark Era, from 10<sup>100</sup> years from now and beyond === |

||

:''From 10<sup>100</sup> years and beyond'' |

|||

[[Image:Photon waves.png|thumb|right|245px|<center>The lowly [[photon]] is now king of the universe as the last of the supermassive black holes evaporate.</center>]] |

[[Image:Photon waves.png|thumb|right|245px|<center>The lowly [[photon]] is now king of the universe as the last of the supermassive black holes evaporate.</center>]] |

||

Revision as of 22:06, 27 July 2008

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Recent observations suggest that the expansion of the universe will continue forever. If so, the universe will cool as it expands, eventually becoming too cold to sustain life. For this reason, this future scenario is popularly called the Big Freeze.[1]

The future of an expanding universe is bleak.[2] If a cosmological constant accelerates the expansion of the universe, clusters of galaxies will rapidly be driven away from each other, leaving observers in different clusters unable to either reach each other or sense each other's presence in any way.[3] Stars are expected to form normally for 1012 to 1014 years, but eventually the supply of gas needed for star formation will be exhausted. Once the last star has exhausted its fuel, stars will then cease to shine.[4], §IID, IIE. The stellar remnants left behind are expected to disappear as their protons decay, leaving behind only black holes which themselves eventually disappear as they emit Hawking radiation.[4], §IV. Ultimately, if the universe reaches a state in which the temperature approaches a uniform value, no further work will be possible, resulting in a final heat death of the universe.[4], §VID.

Cosmology

Indefinite expansion does not determine the spatial curvature of the universe. It can be open (with negative spatial curvature), flat, or closed (positive spatial curvature), although if it is closed, sufficient dark energy must be present to counteract the gravitational attraction of matter and other forces tending to contract the universe. Open and flat universes will expand forever even in the absence of dark energy.[5]

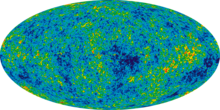

Observations of the cosmic background radiation by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe suggest that the universe is spatially flat and has a significant amount of dark energy.[6] In this case, the universe should continue to expand at an accelerating rate. The acceleration of the universe's expansion has also been confirmed by observations of distant supernovae.[5] If, as in the concordance model of physical cosmology (Lambda-cold dark matter or ΛCDM), the dark energy is in the form of a cosmological constant, the expansion will eventually become exponential, with the size of the universe doubling at a constant rate.

Future history

In the 1970s, the future of an expanding universe was studied by the astrophysicist Jamal Islam[7] and the physicist Freeman Dyson.[8] More recently, the astrophysicists Fred Adams and Gregory Laughlin have divided the past and future history of an expanding universe into five eras. The first, the Primordial Era, is the time in the past just after the Big Bang when stars had not yet formed. The second, the Stelliferous Era, includes the present day and all of the stars and galaxies we see. It is the time during which stars form from collapsing clouds of gas. In the subsequent Degenerate Era, the stars will have burnt out, leaving all stellar-mass objects as stellar remnants—white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes. In the Black Hole Era, white dwarfs, neutron stars, and other smaller astronomical objects have been destroyed by proton decay, leaving only black holes. Finally, in the Dark Era, even black holes have disappeared, leaving only a dilute gas of photons and leptons.[9], pp. xxiv–xxviii.

This future history and the timeline below assume the continued expansion of the universe. If the universe begins to recontract, subsequent events in the timeline may not occur as the Big Crunch, the recontraction of the universe into a hot, dense state similar to that after the Big Bang, will supervene.[9], pp. 190–192;[4], §VA

Timeline

- For the past, including the Primordial Era, see Timeline of the Big Bang.

The Stelliferous Era, from 106 (1 million) years to 1014 (100 trillion) years after the Big Bang

The universe is currently 13.7×109 (13.7 billion) years old.[6] This time is in the Stelliferous Era. About 155 million years after the Big Bang, the first star formed. Since then, stars have formed by the collapse of small, dense core regions in large, cold molecular clouds of hydrogen gas. At first, this produces a protostar, which is hot and bright because of energy generated by gravitational contraction. After the protostar contracts for a while, its center will become hot enough to fuse hydrogen and its lifetime as a star will properly begin.[9], pp. 35–39.

Stars whose mass is very low will eventually exhaust all their fusible hydrogen and then become helium white dwarfs.[10] Stars of low to medium mass will expel some of their mass as a planetary nebula and eventually become a white dwarf; more massive stars will explode in a core-collapse supernova, leaving behind neutron stars or black holes.[11] In any case, although some of the star's matter may be returned to the interstellar medium, a degenerate remnant will be left behind whose mass is not returned to the interstellar medium. Therefore, the supply of gas available for star formation is steadily being exhausted.

The Milky Way Galaxy and the Andromeda Galaxy merge into one galaxy: 3 billion years from now

The Andromeda Galaxy is currently approximately 2.5 million light years away from our galaxy, the Milky Way Galaxy, and the galaxies are moving towards each other at approximately 120 kilometers per second. Approximately three billion years from now, or 17 billion years after the Big Bang, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy may collide with one another and merge into one large galaxy. Because it is not known precisely how fast the Andromeda Galaxy is moving transverse to us, it is not certain that the collision will happen.[12]

Coalescence of Local Group: 1011 (100 billion) to 1012 (1 trillion) years from now

The galaxies in the Local Group, the cluster of galaxies which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, are gravitationally bound to each other. It is expected that between 1011 (100 billion) and 1012 (1 trillion) years from now, their orbits will decay and the entire Local Group will merge into one large galaxy.[4], §IIIA.

Galaxies outside the Local Supercluster are no longer detectable: 2×1012 (2 trillion) years from now

Assuming that dark energy continues to make the universe expand at an accelerating rate, 2×1012 (2 trillion) years from now, all galaxies outside the Local Supercluster will be red-shifted to such an extent that even gamma rays they emit will have wavelengths longer than the size of the observable universe of the time. Therefore, these galaxies will no longer be detectable in any way.[3]

The Degenerate Era, from 1014 (100 trillion) to 1040 years from now

By 1014 (100 trillion) years from now, star formation will end, leaving all stellar objects in the form of degenerate remnants. This period, known as the Degenerate Era, will last until the degenerate remnants finally decay.[4], § III–IV.

Star formation ceases: 1014 (100 trillion) years

It is estimated that in 1014 (100 trillion) years or less, star formation will end.[4], §IID. The least massive stars take the longest to exhaust their hydrogen fuel (see stellar evolution). Thus, the longest living stars in the universe are low-mass red dwarfs, with a mass of about 0.08 solar masses, which have a lifetime of order 1013 (10 trillion) years.[13] Coincidentally, this is comparable to the length of time over which star formation takes place.[4] §IID. Once star formation ends and the least massive red dwarfs exhaust their fuel, nuclear fusion will cease. The low-mass red dwarfs will cool and become white dwarfs.[10] The only objects remaining with more than planetary mass will be brown dwarfs, with mass less than 0.08 solar masses, and degenerate remnants: white dwarfs, produced by stars with initial masses between about 0.08 and 8 solar masses, and neutron stars and black holes, produced by stars with initial masses over 8 solar masses. Most of the mass of this collection, approximately 90%, will be in the form of white dwarfs.[4] §IIE. In the absence of any energy source, all of these formerly luminous bodies will cool and become faint.

The universe will become extremely dark after the last star burns out. Even so, there can still be occasional light in the universe. One of the ways the universe can be illuminated is if two carbon-oxygen white dwarfs with a combined mass of more than the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 solar masses happen to merge. The resulting object will then undergo runaway thermonuclear fusion, producing a Type Ia supernova and dispelling the darkness of the Degenerate Era for a few weeks.[4] §IIIC;[14] If the combined mass is not above the Chandrasekhar limit but is larger than the minimum mass to fuse carbon (about 0.9 solar masses), a carbon star could be produced, with a lifetime of around 106 (1 million) years.[9], p. 91 Also, if two helium white dwarfs with a combined mass of at least 0.3 solar masses collide, a helium star may be produced, with a lifetime of a few hundred million years.[9], p. 91 Finally, if brown dwarfs collide with each other, a red dwarf star may be produced which can survive for 1013 (10 trillion) years.[4] §IIIC.[13]

Planets fall or are flung from orbits by a close encounter with another star: 1015 years from now

Over time, the orbits of planets will decay due to gravitational radiation, or planets will be ejected from their local systems by gravitational perturbations caused by encounters with another stellar remnant.[4], §IIIF, Table I.

Stellar remnants escape galaxies or fall into black holes: 1019 to 1020 years from now

Over time, objects in a galaxy exchange kinetic energy in a process called dynamical relaxation, making their velocity distribution approach the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.[15] Dynamical relaxation can proceed either by close encounters of two stars or by less violent but more frequent distant encounters.[16] In the case of a close encounter, two brown dwarfs or stellar remnants will pass close to each other. When this happens, the trajectories of the objects involved in the close encounter change slightly. After a large number of encounters, lighter objects tend to gain kinetic energy while the heavier objects lose it.[9], pp. 85–87

Because of dynamical relaxation, some objects will gain enough energy to reach galactic escape velocity and depart the galaxy, leaving behind a smaller, denser galaxy. Since encounters are more frequent in the denser galaxy, the process then accelerates. The end result is that most objects are ejected from the galaxy, leaving a small fraction (perhaps 1% to 10%) which fall into the central supermassive black hole.[4], §IIIAD;[9], pp. 85–87

Nucleons start to decay: >1032 years

The subsequent evolution of the universe depends on the existence and rate of proton decay. Experimental evidence shows that if the proton is unstable, it has a half-life of at least 1032 years.[17] If a Grand Unified Theory is correct, then there are theoretical reasons to believe that the half-life of the proton is under 1041 years.[4], §IVA. If not, the proton is still expected to decay, for example via processes involving virtual black holes, with a half-life of under 10200 years.[4], §IVF Neutrons bound into nuclei are also expected to decay with a half-life comparable to the proton's.[4], §IVA

In the event that the proton did not decay at all, stellar-mass objects would still disappear, but more slowly. See Future without proton decay below.

The rest of this timeline assumes that the proton half-life is approximately 1037 years.[4], §IVA. Shorter or longer proton half-lives will accelerate or retard the process. This means that after 1037 years, one-half of all baryonic matter will have been converted into gamma ray photons and leptons through proton decay.

All nucleons decay: 1040 years

Given our assumed half-life of the proton, nucleons (protons and bound neutrons) will have undergone roughly 1,000 half-lives by the time the universe is 1040 years old. To put this into perspective, there are an estimated 1080 protons currently in the universe.[18] This means that the number of nucleons will be slashed in half 1,000 times by the time the universe is 1040 years old. Hence, there will be roughly ½1,000 (approximately 10–301) as many nucleons remaining as there are today; that is, zero nucleons remaining in the universe at the end of the Degenerate Age. Effectively, all baryonic matter will have been changed into photons and leptons.

The Black Hole Era, from 1040 years to 10100 years from now

After 1040 years, black holes will dominate the universe. They will slowly evaporate via Hawking radiation.[4], §IVG. A black hole with a mass of around 1 solar mass will vanish in around 2×1066 years. As the lifetime of a black hole is proportional to the cube of its mass, more massive black holes take longer to decay. A supermassive black hole with a mass of 1011 (100 billion) solar masses will evaporate in around 2×1099 years.[19]

Hawking radiation has a thermal spectrum. During most of a black hole's lifetime, the radiation has a low temperature and is mainly in the form of massless particles such as photons and gravitons. As the black hole's mass decreases, its temperature increases, becoming comparable to the Sun's by the time the black hole mass has decreased to 1019 kilograms. The hole then provides a temporary source of light during the general darkness of the Black Hole Era. During the last stages of its evaporation, a black hole will emit not only massless particles but also heavier particles such as electrons, positrons, protons and antiprotons.[9], pp. 148–150.

The Dark Era, from 10100 years from now and beyond

After all the black holes have evaporated (and after all the ordinary matter made of protons has disintegrated, if protons are unstable), the universe will be nearly empty. Photons, neutrinos, electrons and positrons will fly from place to place, hardly ever encountering each other.

By this era, with only very diffuse matter remaining, activity in the universe will have tailed off dramatically, with very low energy levels and very large time scales. Electrons and positrons drifting through space will encounter one another and occasionally form positronium atoms. These structures are unstable, however, and their constituent particles must eventually annihilate.[4], §VF3. Other low-level annihilation events will also take place, albeit very slowly.

The universe now reaches an extremely low-energy state. What happens after this is speculative. It's possible that a Big Rip event may occur far off into the future. Also, the universe may enter a second inflationary epoch, or, assuming that the current vacuum state is a false vacuum, the vacuum may decay into a lower-energy state.[4], §VE. Finally, the universe may settle into this state forever, achieving true heat death.[4], §VID.

Future without proton decay

If the proton does not decay, stellar-mass objects will still become black holes, but more slowly. The following timeline assumes that proton decay does not take place.

Matter is liquid at zero temperature: 1065 years from now

With a timescale of approximately 1065 years, apparently rigid objects such as rocks will be able to rearrange their atoms and molecules via quantum tunnelling, behaving as a liquid does, but more slowly.[8]

Matter decays into iron: 101500 years from now

In 101500 years, cold fusion occurring via quantum tunnelling should make the light nuclei in ordinary matter fuse into iron-56 nuclei (see isotopes of iron.) Fission and alpha-particle emission should make heavy nuclei also decay to iron, leaving stellar-mass objects as cold spheres of iron.[8]

Collapse of iron star to black hole: 10(1026) to 10(1076) years from now

Quantum tunnelling should also turn large objects into black holes. Depending on the assumptions made, the time this takes to happen can be calculated as from years to years. (To calculate the value of such numbers, see tetration.) Quantum tunnelling may also make iron stars collapse into neutron stars in around years.[8]

Graphical timeline

See also

- Heat death of the universe

- 1 E19 s and more

- Second law of thermodynamics

- Big Rip

- Big Crunch

- Big Bounce

- Big Bang

- Cyclic model

- Dyson's eternal intelligence

- Final anthropic principle

- Ultimate fate of the Universe

- Graphical timeline of the Stelliferous Era

- Graphical timeline from Big Bang to Heat Death. This timeline uses the loglog scale for comparison with the graphical timeline included in this article.

- Graphical timeline of our universe. This timeline uses the more intuitive linear time, for comparison with this article.

- Timeline of the Big Bang

- Graphical timeline of the Big Bang

- The Last Question, a short story by Isaac Asimov which considers the inevitable oncome of heat death in the universe and how it may be reversed.

References

- ^ WMAP - Fate of the Universe, WMAP's Universe, NASA. Accessed on line July 17, 2008.

- ^ "Heroic" research confirms universe's bleak future, Anna Salleh, May 27, 2002, news, Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Accessed on line July 18, 2008.

- ^ a b Life, the Universe, and Nothing: Life and Death in an Ever-expanding Universe, Lawrence M. Krauss and Glenn D. Starkman, Astrophysical Journal, 531 (March 1, 2000), pp. 22–30. doi:10.1086/308434. Bibcode:2000ApJ...531...22K.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, Reviews of Modern Physics 69, #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337 arXiv:astro-ph/9701131.

- ^ a b Chapter 7, Calibrating the Cosmos, Frank Levin, New York: Springer, 2006, ISBN 0-387-30778-8.

- ^ a b Five-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Data Processing, Sky Maps, and Basic Results, G. Hinshaw et al., The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series (2008), submitted, arXiv:0803.0732, Bibcode:2008arXiv0803.0732H.

- ^ Possible Ultimate Fate of the Universe, Jamal N. Islam, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 18 (March 1977), pp. 3–8, Bibcode:1977QJRAS..18....3I

- ^ a b c d Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe, Freeman J. Dyson, Reviews of Modern Physics 51 (1979), pp. 447–460, doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.51.447.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Five Ages of the Universe, Fred Adams and Greg Laughlin, New York: The Free Press, 1999, ISBN 0-684-85422-8.

- ^ a b The End of the Main Sequence, Gregory Laughlin, Peter Bodenheimer, and Fred C. Adams, The Astrophysical Journal, 482 (June 10, 1997), pp. 420–432. Bibcode:1997ApJ...482..420L. doi:10.1086/304125.

- ^ How Massive Single Stars End Their Life, A. Heger, C. L. Fryer, S. E. Woosley, N. Langer, and D. H. Hartmann, Astrophysical Journal 591, #1 (2003), pp. 288–300.

- ^ The Great Milky Way-Andromeda Collision, John Dubinski, Sky and Telescope, October 2006. Bibcode:2006S&T...112d..30D.

- ^ a b Adams & Laughlin (1997), §IIA and Figure 1.

- ^ The Future of the Universe, Michael Richmond, lecture notes, Physics 240, Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed on line July 8, 2008.

- ^ p. 428, A deep focus on NGC 1883, A. L. Tadross, Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India 33, #4 (December 2005), pp. 421–431, Bibcode:2005BASI...33..421T.

- ^ Reading notes, Liliya L. R. Williams, Astrophysics II: Galactic and Extragalactic Astronomy, University of Minnesota, accessed on line July 20, 2008.

- ^ Theory: Decays, SLAC Virtual Visitor Center. Accessed on line June 28, 2008.

- ^ Solution, exercise 17, One Universe: At Home in the Cosmos, Neil de Grasse Tyson, Charles Tsun-Chu Liu, and Robert Irion, Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2000. ISBN 0-309-06488-0.

- ^ Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole, Don N. Page, Physical Review D 13 (1976), pp. 198–206. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198. See in particular equation (27).