Julian Assange: Difference between revisions

replaced poor quality pic with non exact date, with better quality pic with exact date. |

fix img |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name = Julian Assange |

| name = Julian Assange |

||

| image = |

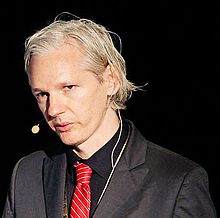

| image = Julian Assange 26C3.jpg |

||

| caption = Assange in 2009 |

| caption = Assange in 2009 |

||

| birth_date = 1971 <!--Template:Dob says not to use this when exact age is not known--> |

| birth_date = 1971 <!--Template:Dob says not to use this when exact age is not known--> |

||

Revision as of 20:37, 10 September 2010

This article is about a person involved in a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses. |

Julian Assange | |

|---|---|

Assange in 2009 | |

| Born | 1971 Townsville, Queensland, Australia |

| Occupation(s) | Currently Editor in chief and spokesperson for Wikileaks Previously Journalist, programmer, internet activist, and internet hacker |

| Board member of | Wikileaks |

| Awards | Amnesty International UK Media Awards 2009, Sam Adams Award 2010 |

Julian Paul Assange (Template:Pron-en ə-SAHNZH; born 1971) is an Australian internet activist best known for his involvement with Wikileaks, a whistleblower website. Assange was a physics and mathematics student, a hacker and a computer programmer, before taking on his current role as Wikileaks' spokesperson and editor-in-chief.[1]

Life and career

Early life and education

Assange's parents ran a touring theatre company. In 1979, his mother remarried to a musician who belonged to a cult led by Anne Hamilton-Byrne. The new couple had a son, but broke up in 1982 and engaged in a custody struggle for his half-brother. His mother then took both children into hiding for the next five years. Assange left home in 1987. In all, he had moved several dozen times in his childhood, frequently switching between formal and home schooling and later attending several different universities at various times in Australia.[2] He has been described as being largely self-taught and widely read on science and mathematics.[3] From 2003 to 2006, Assange studied physics and mathematics at the University of Melbourne but does not claim a degree.[2] On his personal web page Assange described how he represented his University at the Australian National Physics Competition around 2005.[4] He has also studied philosophy and neuroscience.[5]

Hacking charges

In the late 1980s he was a member of a hacker group named "International Subversives," possibly going by the handle "Mendax" (derived from a phrase of Horace: "splendide mendax," or "nobly untruthful"). In 1992, he pleaded guilty to 24 charges of hacking.[2] He was the subject of a 1991 raid of his Melbourne home by the Australian Federal Police.[6] He was reported to have accessed various computers belonging to an Australian university, Canadian telecommunications company Nortel,[2] and other organisations via modem[7] to test their security flaws; he later pleaded guilty to 24 charges of hacking and was released on bond for good conduct after being fined AU$2100.[3]

In 1989, Assange started living with his girlfriend and soon they had a son. She separated from him after the 1991 police raid and took their son.[8] They engaged in a lengthy custody struggle because her new partner did not meet his approval.[2]

Career as computer programmer

Starting in 1994, Assange lived in Melbourne as a programmer and a developer of free software.[3] In 1995, Assange wrote Strobe, the first free and open source port scanner.[9][10] He helped to write the 1997 book Underground: Tales of Hacking, Madness and Obsession on the Electronic Frontier which credits him as researcher and reports his history with International Subversives.[11] Starting around 1997 he co-invented "Rubberhose deniable encryption," a cryptographic concept made into a software package for Linux designed to provide plausible deniability against rubber-hose cryptanalysis,[12] which he originally intended "as a tool for human rights workers who needed to protect sensitive data in the field."[13] Other free software that he has authored or co-authored includes the Usenet caching software NNTPCache[14] and Surfraw, a command line interface for web-based search engines. In 1999, Assange registered the domain leaks.org; "but," he says, "then I didn't do anything with it."[15]

WikiLeaks

Wikileaks was founded in 2006.[2][16] Assange now sits on its nine-member advisory board,[17] and is a prominent media spokesman on its behalf. While newspapers have described him as a "director"[18] or "founder"[6] of Wikileaks, Assange has said "I don’t call myself a founder,"[19] but he does describe himself as the editor in chief of Wikileaks,[20] and has stated that he has the final decision in the process of vetting documents submitted to the site.[21] Like all others working for the site, Assange is an unpaid volunteer.[19][22][23][24] [25]

Awards

Assange was the winner of the 2009 Amnesty International Media Award (New Media),[26] awarded for exposing extrajudicial assassinations in Kenya with the investigation The Cry of Blood – Extra Judicial Killings and Disappearances.[27] In accepting the award, he said: "It is a reflection of the courage and strength of Kenyan civil society that this injustice was documented. Through the tremendous work of organisations such as the Oscar foundation, the KNHCR, Mars Group Kenya and others we had the primary support we needed to expose these murders to the world."[28] He also won the 2008 Economist Index on Censorship Award.[29] Assange says that Wikileaks has released more classified documents than the rest of the world press combined: "That's not something I say as a way of saying how successful we are – rather, that shows you the parlous state of the rest of the media. How is it that a team of five people has managed to release to the public more suppressed information, at that level, than the rest of the world press combined? It's disgraceful."[16]

Public appearances

Assange has said he is constantly on the move, living in airports.[30] He has lived for periods in Australia, Kenya and Tanzania, and began renting a house in Iceland on 30 March 2010, from which he and other activists, including Birgitta Jónsdóttir, worked on the 'Collateral Murder' video.[2] He has appeared at media conferences such as New Media Days '09 in Copenhagen,[31] the 2010 Logan Symposium in Investigative Reporting at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism,[32] and at hacker conferences, notably the 25th and 26th Chaos Communication Congress.[33] In the first half of 2010, he appeared on Al Jazeera English, MSNBC, Democracy Now!, RT, and The Colbert Report to discuss the release of the 12 July 2007 Baghdad airstrike video by Wikileaks.

On 3 June He appeared via video conferencing at the Personal Democracy Forum conference with Daniel Ellsberg.[34][35] Daniel Ellsberg told MSNBC "the explanation he [Assange] used" for not appearing in person in the USA was that "it was not safe for him to come to this country."[36] On 11 June he was to appear on a Showcase Panel at the Investigative Reporters and Editors conference in Las Vegas,[37] but there are reports that he cancelled several days prior.[38] On 10 June 2010, it was reported[39] that Pentagon officials are trying to determine his whereabouts.[40][41][42][43][44][45] Based on this, there have been reports that U.S. officials want to apprehend Assange.[46] Ellsberg said that the arrest of Bradley Manning and subsequent speculation by U.S. officials about what Assange may be about to publish "puts his well-being, his physical life, in some danger now."[36] In The Atlantic, Marc Ambinder called Ellsberg's concerns "ridiculous," and said that "Assange's tendency to believe that he is one step away from being thrown into a black hole hinders, and to some extent discredits, his work."[47] In Salon.com, Glenn Greenwald questioned "screeching media reports" that there was a "manhunt" on Assange underway, arguing that they were only based on comments by "anonymous government officials" and might even serve a campaign by the U.S. government, by intimidating possible whistleblowers.[42]

On 21 June 2010 Assange took part in a hearing in Brussels, Belgium, appearing in public for the first time in nearly a month.[48] He was a member on a panel that discussed Internet censorship and expressed his worries over the recent filtering in countries such as Australia. He also talked about secret gag orders preventing newspapers from publishing information about specific subjects and even divulging the fact that they are being gagged. Using an example involving The Guardian, he also explained how newspapers are altering their online archives sometimes by removing entire articles.[49][50] He told The Guardian that he does not fear for his safety but is on permanent alert and will avoid travel to America, saying "[U.S.] public statements have all been reasonable. But some statements made in private are a bit more questionable." He said "politically it would be a great error for them to act. I feel perfectly safe but I have been advised by my lawyers not to travel to the U.S. during this period."[48]

On 17 July, Jacob Appelbaum spoke on behalf of WikiLeaks at the 2010 Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) conference in New York City, replacing Assange due to the presence of federal agents at the conference.[51][52] He announced that the WikiLeaks submission system was again up and running, after it had been temporarily suspended.[51][53] Assange was a surprise speaker at a TED conference on 19 July 2010 in Oxford, and confirmed that WikiLeaks was now accepting submissions again.[54][55][56] On 26 July, after the release of the Afghan War Diary Assange appeared at the Frontline Club for a press conference.[57]

Descriptions of Assange

Assange advocates a "transparent" and "scientific" approach to journalism, saying that "you can’t publish a paper on physics without the full experimental data and results; that should be the standard in journalism."[58][59] In 2006, CounterPunch called him Australia's most infamous former computer hacker."[60] The Age has called him "one of the most intriguing people in the world" and "internet's freedom fighter."[15] Assange has called himself "extremely cynical."[15] The Personal Democracy Forum said that as a teenager he was "Australia's most famous ethical computer hacker."[5] He has been described as thriving on intellectual battle.[61]

Pentagon Papers whistle-blower Daniel Ellsberg said that Assange "is serving our [American] democracy and serving our rule of law precisely by challenging the secrecy regulations, which are not laws in most cases, in this country." On the issue of national security considerations for the U.S., Ellsberg added that "any serious risk to that national security is extremely low. There may be 260,000 diplomatic cables. It’s very hard to think of any of that which could be plausibly described as a national security risk. Will it embarrass diplomatic relationships? Sure, very likely—all to the good of our democratic functioning."[62] Against this Daniel Yates, a former British military intelligence officer, believes Assange has jeopardised the lives of Afghan civilians: "The logs contain detailed personal information regarding Afghan civilians who have approached NATO soldiers with information. It is inevitable that the Taliban will now seek violent retribution on those who have co-operated with NATO. Their families and tribes will also be in danger."[63] Responding to the criticism, Assange said in August 2010 that 15,000 documents are still being reviewed "line by line," and that the names of "innocent parties who are under reasonable threat" will be removed.[64] Before the release of the Afghan War Diaries in July, Wikileaks contacted the White House in writing, asking that it identify names that might draw reprisals, but received no response.[65]

2010 Legal difficulties

In May 2010, upon landing in Australia, his Australian passport was taken from him, and when it was returned he was told it was to be cancelled because it was worn, and that he was otherwise free to travel.[66][67] According to the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Defence and Justice departments are exploring possible legal options for prosecuting Assange and others on grounds that they encouraged the theft of government property.[68]

On 20 August 2010, an arrest warrant was issued, and later cancelled, for Assange in Sweden in connection with an allegation that he had raped a woman in Enköping on the weekend of 14 August 2010 after a seminar, and had two days later, on 16 August 2010, sexually harassed a second woman whom he been staying with in Stockholm.[69]

Within 24 hours the chief prosecutor Eva Finné withdrew the warrant saying there was no reason to suspect he had committed rape, although Karin Rosander of the Swedish Prosecution Authority said he was still being investigated for a lesser charge of molestation—which covers reckless conduct or inappropriate physical contact — a charge not serious enough to trigger an arrest warrant. Assange said the charges were without basis and expressed concern about the timing.[70] He was questioned by police in relation to the molestation allegation for an hour on 31 August,[71] and on 1 September a senior Swedish prosecutor re-opened the rape investigation saying that new information had come in. The woman's lawyer, Claes Borgström, had earlier appealed against the decision not to proceed.[72]

References

- ^ "Profile: Julian Assange, the man behind Wikileaks". The Sunday Times. UK. 11 April 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Khatchadourian, Raffi (7 June 2010). "No Secrets: Julian Assange's Mission for Total Transparency". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Lagan, Bernard (10 April 2010). "International man of mystery". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Assagne, Julian (12 July 2006). "Wed 12 Jul 2006 : The cream of Australian Physics". IQ.ORG. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007.

A year before, also at ANU, I represented my university at the Australian National Physics Competition. At the prize ceremony, the head of ANU physics, motioned to us and said, 'You are the cream of Australian physics'.

- ^ a b "PdF Conference 2010: Speakers". Personal Democracy Forum. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b Guilliatt, Richard (30 May 2009). "Rudd Government blacklist hacker monitors police". The Australian. Retrieved 16 June 2010. [lead-in to a longer article in that day's The Weekend Australian Magazine]

- ^ Weinberger, Sharon (7 April 2010). "Who Is Behind WikiLeaks?". AOL News. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Paranoid, anarchic... is WikiLeaks boss a force for good or chaos? 27 July 2010

- ^ In this limited application strobe is said to be faster and more flexible than ISS2.1 (an expensive, but verbose security checker by Christopher Klaus) or PingWare (also commercial, and even more expensive). See Strobe v1.01: Super Optimised TCP port surveyor

- ^ "strobe-1.06: A super optimised TCP port surveyor". The Porting And Archive Centre for HP-UX. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Dreyfus, Suelette (1997). Underground: Tales of Hacking, Madness and Obsession on the Electronic Frontier. ISBN 1-86330-595-5.

- ^ Singel, Ryan (3 July 2008). "Immune to Critics, Secret-Spilling Wikileaks Plans to Save Journalism ... and the World". Wired. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Dreyfus, Suelette. "The Idiot Savants' Guide to Rubberhose". Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "NNTPCache: Authors". Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Barrowclough, Nikki (22 May 2010). "Keeper of secrets". The Age. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b "The secret life of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange". The Sydney Morning Herald. 22 May 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "WikiLeaks:Advisory Board". Wikileaks. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (5 April 2010). "Wikileaks reveals video showing US air crew shooting down Iraqi civilians". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b Interview with Julian Assange, spokesperson of WikiLeaks: Leak-o-nomy: The Economy of WikiLeaks

- ^ "Julian Assange: Why the World Needs WikiLeaks". Huffington Post. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Kushner, David (6 April 2010). "Inside WikiLeaks' Leak Factory". Mother Jones. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ WikiLeaks:Advisory Board – Julian Assange, investigative journalist, programmer and activist (short biography on the Wikileaks home page)

- ^ Harrell, Eben, (26 July 2010) 2-Min. Bio WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange 26 July 2010 Time.

- ^ Rumored Manhunt for Wikileaks Founder and Arrest of Alleged Leaker of Video Showing Iraq Killings – video report by Democracy Now!

- ^ Adheesha Sarkar (10 August 2010). "The People'S Spy". Telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Nystedt, Dan (27 October 2009). "Wikileaks leader talks of courage and wrestling pigs". Computerworld. International Data Group. IDG News Service. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Report on Extra-Judicial Killings and Disappearances 1 March 2009

- ^ “WikiLeaks wins Amnesty International 2009 Media Award for exposing Extra judicial killings in Kenya”.. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange at the centre for investigative journalism". tcij.org. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Defending the Leaks: Q&A with WikiLeaks' Julian Assange 27 July 2010

- ^ "The Subtle Roar of Online Whistle-Blowing". New Media Days. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Video of Julian Assange on the panel at the 2010 Logan Symposium, 18 April 2010

- ^ "25C3: Wikileaks". Events.ccc.de. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "PdF Conference 2010 | June 3–4 | New York City | Personal Democracy Forum". Personaldemocracy.com. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Hendler, Clint (3 June 2010). "Ellsberg and Assange". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ a b Hamsher, Jane (11 June 2010). "Transcript: Daniel Ellsberg Says He Fears US Might Assassinate Wikileaks Founder | FDL Action". Firedoglake. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Showcase Panels". data.nicar.org. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin; Zetter, Kim (11 June 2010). "Wikileaks Commissions Lawyers to Defend Alleged Army Source". Wired. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (10 June 2010). "Wikileaks Founder Julian Assange Hunted by Pentagon Over Massive Leak". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (Friday 11 June 2010 19.02 BST). "Pentagon hunts WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in bid to gag website". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "Media" ignored (help); Text "The Guardian" ignored (help) - ^ Shenon, Philip (10 June 2010). "Wikileaks Founder Julian Assange Hunted by Pentagon Over Massive Leak – The Daily Beast". Pentagon Manhunt. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Glenn (Friday, 18 Jun 2010 08:20 ET). "The strange and consequential case of Bradley Manning, Adrian Lamo and WikiLeaks - Glenn Greenwald - Salon.com". Salon Media Group (Salon.com). Retrieved 18 June 2010.

On 10 June, former New York Times reporter Philip Shenon, writing in The Daily Beast, gave voice to anonymous "American officials" to announce that "Pentagon investigators" were trying "to determine the whereabouts of the Australian-born founder of the secretive website Wikileaks [Julian Assange] for fear that he may be about to publish a huge cache of classified State Department cables that, if made public, could do serious damage to national security." Some news outlets used that report to declare that there was a "Pentagon manhunt" underway for Assange – as though he's some sort of dangerous fugitive.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lauder, Simon (18 June 2010). "Wikileaks founder fears for his life – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". ABC Online. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Bosker, Bianca (11 June 2010). "Julian Assange, Wikileaks Founder, Hunted By Pentagon". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Stein, Jeff (18 June 2010; 5:39 PM ET). "SpyTalk – Wikileaks founder in hiding, fearful of arrest". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Taylor, Jerome (12 June 2010). "Pentagon rushes to block release of classified files on Wikileaks". The Independent. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Ambinder, Marc. "Does Julian Assange Have Reason to Fear the U.S. Government?". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b "Wikileaks founder Julian Assange emerges from hiding". Telegraph. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Hearing: (Self) Censorship New Challenges for Freedom of Expression in Europe". Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (21 June 2010). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange breaks cover but will avoid America". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ a b Singel, Ryan (19 July 2010). "Wikileaks Reopens for Leakers". Wired. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan (16 July 2010). "Feds look for Wikileaks founder at NYC hacker event". News.cnet.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Jacob Appelbaum, WikiLeaks keynote: 2010 Hackers on Planet Earth conference, New York City, 17 July 2010

- ^ "Surprise speaker at TEDGlobal: Julian Assange in Session 12". Blog.ted.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange: Why the world needs WikiLeaks". Ted.com. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange - TED Talk - Wikileaks". Geekosystem. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Frontline Club 07/26/10 04:31AM". Ustream.tv. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "'A real free press for the first time in history': WikiLeaks editor speaks out in London". Blogs.journalism.co.uk. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Julian Assange: the hacker who created WikiLeaks". Csmonitor.com. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Julian Assange: The Anti-Nuclear WANK Worm. The Curious Origins of Political Hacktivism CounterPunch, 25 November/ 26 2006 Cite error: The named reference "wankworm" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Julian Assange, monk of the online age who thrives on intellectual battle 1 August 2010

- ^ "Daniel Ellsberg: Wikileaks' Julian Assange "in Danger"". The Daily Beast. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010. Cite error: The named reference "ellsbergdanger" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Yates, Daniel (30 July 2010). "Leaked Afghan files 'put civilians at risk'". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Sweden Withdraws Arrest Warrant for Embattled WikiLeaks Founder". .voanews.com. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Why Wikileaks Must Be Protected". Zcommunications.org. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Arup, Tom (17 May 2010). "Australian Wikileak founder's passport confiscated". The Age. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Davis, Mark (16 May 2010). "SBS Dateline: The Whistleblower". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "Update: Assange Arrest Warrant Dropped As Wikileaks Warns of 'Dirty Tricks'". Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Cody, Edward (9 September 2010). "WikiLeaks stalled by Swedish inquiry into allegations of rape by founder Assange". Washington Post. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (22 August 2010). "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange denies rape allegations". The Guardian.

- ^ "WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange questioned by police". The Guardian. 31 August 2010.

- ^ "Sweden reopens investigation into rape claim against Julian Assange". The Guardian. 1 September 2010.

Further reading

- Archived versions of the home page on Julian Assange's web site iq.org (at the Internet Archive)

- Video profile on SBS Dateline

- WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange: "Transparent Government Tends to Produce Just Government"

- Symington, Annabel (1 September 2009). "Exposed: Wikileaks' secrets". Wired. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Meet the Aussie behind Wikileaks". Fairfax New Zealand. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Julian Assange: The end of secrets? 16 August 2010

- "Meet the Aussie behind Wikileaks". Fairfax New Zealand. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Stephen Colbert (interviewer), Julian Assange (subject) (12 April 2010). "Julian Assange Unedited Interview". The Colbert Report. Episode 6049. Comedy Central.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|began=,|episodelink=,|city=,|ended=,|transcripturl=, and|seriesno=(help); Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - "WikiLeaks editor on Apache combat video: No excuse for US killing civilians". RussiaToday. 6 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "WikiLeaks Release 1.0: Insight into vision, motivation and innovation". 26th Chaos Communication Congress. 30 December 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- "MSNBC Panel discusses WikiLeaks.org's "Collateral Murder" Video – Part 1". 5 April 2010.

- Goodman, Amy (6 April 2010). "Massacre Caught on Tape: US Military Confirms Authenticity of Their Own Chilling Video Showing Killing of Journalists". Democracy Now. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- "Video of US attack in Iraq 'genuine'". AlJazeeraEnglish. 5 April 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.