History of crossbows: Difference between revisions

merged Ancient Greeks and Europe to avoid POV that the crossbow is Greek in origin |

Haudcivitas (talk | contribs) modern use |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

In some countries they are still used for [[hunting]], such as in a few states within the USA, parts of Asia and Australia or Africa. Other uses with special projectiles are in [[whale]] research to take [[blubber]] [[biopsy]] samples without harming the whales. <ref>[http://whale.wheelock.edu/bwcontaminants/st_lawrence.html The St. Lawrence<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

In some countries they are still used for [[hunting]], such as in a few states within the USA, parts of Asia and Australia or Africa. Other uses with special projectiles are in [[whale]] research to take [[blubber]] [[biopsy]] samples without harming the whales. <ref>[http://whale.wheelock.edu/bwcontaminants/st_lawrence.html The St. Lawrence<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

=== Active military and police usage === |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Peruvian_crossbow_usage.jpg|Peruvian soldiers equipped with recurve crossbows and ropes. |

|||

Image:Serbia_crossbow_usage.jpg|Serbian special forces demonstrating a crossbow to the Minister of Defence. |

|||

Image:Chinese_crossbow_man.jpg|Chinese PLA soldier training with crossbow, alongside firearms. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

In the Americas, the [[Peruvian]] army (Ejército) equips some soldiers with crossbows and rope, to establish a [[zip-line]] in difficult terrain.<ref>[http://www.saorbats.com.ar/GaleriaSaorbats/Peruffaa04/images/b2aBriFFEE2_EP_jpg.jpg Ejercito prepare for deployment.]</ref> In Brazil the CIGS (Jungle Warfare Training Center) also trains soldiers in the use of crossbows.<ref>[http://www.militaryphotos.net/forums/showthread.php?t=23940 CIGS information thread].</ref><ref>[http://www.segurancaedefesa.com/Besta.jpg CIGS photograph].</ref> |

|||

In Europe, British based Barnett International supplied crossbows to [[Serbian]] forces which were later used in [[ambush]] and anti-sniper operations against the [[Kosovo Liberation Army]] during the [[Kosovo War]]<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/1999/aug/09/balkans The Guardian].</ref>. Whitehall launched an investigation, though the department of trade and industry established that not being "on the military list" crossbows were not covered by such export regulations. Paul Beaver of Jane's defence publications commented that, "They are not only a silent killer, they also have a psychological effect". On February 15 2008 Serbian Minister of Defence [[Dragan Sutanovac]] was pictured testing a Barnett crossbow during a public exercise of the Serbian army's Special Forces in Nis, 200km south of capital [[Belgrade]].<ref>[http://www.daylife.com/photo/04ZU4Zr0xS4IA Day Life Serbia report]</ref> Special forces in both [[Greece]] and [[Turkey]] also continue to employ the crossbow.<ref>[http://i96.photobucket.com/albums/l189/KORNET-E/162.jpg Greek soldiers uses crossbow].</ref><ref>[http://i96.photobucket.com/albums/l189/KORNET-E/crosbow.jpg Turkish special ops].</ref> |

|||

Few modern military units are equipped with crossbows as lower noise alternatives to suppressed firearms. |

|||

In Asia, [[Chinese]] armed forces use crossbows at all unit levels from traffic police to the special forces units of the [[People's Liberation Army]].<ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2g--DrrV2k Chinese news report on crossbows].</ref><ref>[http://www.chinacartimes.com/wp-content/2007/09/crossbow.jpg Chinese traffic police using crossbows].</ref><ref>[http://xmb.stuffucanuse.com/xmb/viewthread.php?action=attachment&tid=4207&pid=12285 Chinese special forces with crossbows].</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 14:34, 1 December 2008

This history of crossbows documents the historical development and use of the crossbow.

It is not clear exactly where and when the crossbow originated, but there is undoubted evidence that it was used for military purposes from the second half of the 4th century BC onwards.

Europe

The earliest date for the crossbow is from the 5th century BC,[1] from the Greek world; this was a giant crossbow known as a ballista, which Bernard Brodie and Fawn McKay Brodie say was a much larger version of the handheld crossbow that was not seen in Europe until the 10th century.[2] The gastraphetes was a large artillery crossbow mounted on a heavy stock with a lower and upper section, the lower being the case fixed to the bow and the upper being the slider which had the same dimensions as the case.[3] The gastraphetes, meaning "belly-bow",[3] was called as such because the concave withdrawal rest at one end of the stock was placed against the stomach of the operator, which he could press to withdraw the slider before attaching a string to the trigger and loading the bolt; this could thus store more energy than regular Greek bows.[4] It was used in the Siege of Motya in 397 BC. This was a key Carthaginian stronghold in Sicily, as described in the 1st century AD by Heron of Alexandria in his book Belopoeica.[5] This date for the introduction of the crossbow in the Mediterranean is not accepted without doubt because of the temporal difference between writer and event and the lack of other sources stating the same. Alexander's siege of Tyre in 332 BC provides reliable sources for the use of these weapons by the Greek besiegers.[6]

The efficiency of the gastraphetes was improved by introducing the ballista. Its application in sieges and against rigid infantry formations featured more and more powerful projectiles, leading to technical improvements and larger ballistae. The smaller sniper version was often called Scorpio.[7] An example for the importance of ballistae in Hellenistic warfare is the Helepolis, a siege tower employed by Demetrius during the Siege of Rhodes in 305 BC. At each level of the moveable tower were several ballistae. The large ballistae at the bottom level were designed to destroy the parapet and clear it of any hostile troop concentrations while the small armorbreaking scorpios at the top level sniped at the besieged. This suppressive shooting would allow them to mount the wall with ladders more safely.[8]

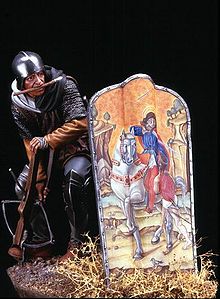

The use of crossbows in Medieval warfare dates back to Roman times and is again evident from the battle of Hastings until about 1500 AD. They almost completely superseded hand bows in many European armies in the twelfth century for a number of reasons. Although a longbow had greater range, could achieve comparable accuracy and faster shooting rate than an average crossbow, crossbows could release more kinetic energy and be used effectively after a week of training, while a comparable single-shot skill with a longbow could take years of practice. In the armies of Europe,[9] mounted and unmounted crossbowmen, often mixed with javeliners and archers, occupied a central position in battle formations. Usually they engaged the enemy in offensive skirmishes before an assault of mounted knights. Crossbowmen were also valuable in counterattacks to protect their infantry. The rank of commanding officer of the crossbowmen corps was one of the highest positions in any army of this time. Along with polearm weapons made from farming equipment, the crossbow was also a weapon of choice for insurgent peasants such as the Taborites. Famous were the Genoese crossbowmen who hired as mercenaries for many countries in medieval Europe, while the crossbow also played an important role in anti-personnel defence of ships.[10]

Crossbowmen among the Flemish citizens,[9] in the army of Richard Lionheart, and others, could have up to two servants, two crossbows and a pavise shield to protect the men. Then one of the servants had the task of reloading the weapons, while the second subordinate would carry and hold the pavise (the archer himself also wore protective armor). Such a three-man team could shoot 8 shots per minute, compared to a single crossbowman's 3 shots per minute. The archer was the leader of the team, the one who owned the equipment, and the one who received payment for their services. The payment for a crossbow mercenary was higher than for a longbow mercenary, but the longbowman did not have to pay a team of assistants and his equipment was cheaper.

Mounted knights armed with lances proved ineffective against formations of pikemen combined with crossbowmen whose weapons could penetrate most knights' armor. The invention of pushlever and ratchet drawing mechanisms enabled the use of crossbows on horseback., leading to the development of new cavalry tactics. Knights and mercenaries deployed in triangular formations, with the most heavily armored knights at the front. Some of these riders would carry small, powerful all-metal crossbows of their own. Crossbows were eventually replaced in warfare by gunpowder weapons, although early guns had slower rates of fire and much worse accuracy than contemporary crossbows. Later, similar competing tactics would feature harquebusiers or musketeers in formation with pikemen, pitted against cavalry firing pistols or carbines.

Up until the seventeenth century most beekeepers in Europe kept their hives spread across the woods and had to defend them against bears. Therefore their guild was granted the right to bear arms and is commonly depicted carrying heavy crossbows.

Asia

Throughout the southeastern Asia the crossbow is still used by primitive and tribal peoples both for hunting and war, from the Assamese mountains through Burma, Siam and to the confines of Indo-China. The peoples of the northeastern Asia possess it also, both as weapon and toy, but use it mainly in the form of unattended traps; this is true of the Yakut, Tungus, and Chukchi, even of the Ainu in the east. There seems to be no way of answering the question whether it first arose among the barbaric forefathers of these Asian peoples before the rise of the Chinese culture in their midst, and then underwent its technical development only therein, or whether it spread outwards from China to all the environing peoples. The former seems the more probable hypothesis, given the further linguistic evidence in its support.[11]

The earliest documention of a Chinese crossbow is in scripts from the 4th–3rd century BC attributed to the followers of Mozi. This source refers the use of a giant crossbow catapult to the 6th to 5th century BC, corresponding to the late Spring and Autumn Period. The date is several centuries before the appearance of the manuscript. As a result the dating from the source can not be used without doubt to determine when the use of crossbows started in Chinese history, although the age of the source can.[12] Sun Tzu's influential book The Art of War (first appearance dated in between 500 BC to 300 BC[13]) refers in chapter V to the traits and in XII to the use of crossbows.[14] One of the earliest reliable records of this weapon in warfare is from an ambush, the Battle of Ma-Ling in 341 BC. By the 200s BC, the crossbow (nǔ, 弩) was well developed and quite widely used in China.

There is also archaeological evidence. Donald B. Wagner writes that bronze and iron crossbow bolts found at Yutaishan, Jiangling County, Hubei province—located in what was then the ancient State of Chu—can be dated to the Warring States Period (403–221 BC), perhaps as far back as the mid 5th century BC.[15] Several remains of crossbows have been found among the soldiers of the Terracotta Army in the tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang (260-210 BC).[16] In China were developed the repeating crossbow and multiple bow arcuballistas.

While discussing advantages and disadvantages of both the nomadic Xiongnu and Han armies in a memorandum to the throne in 169 BC, the official Chao Cuo (d. 154 BC) deemed the crossbow and repeating crossbow of Han armies superior to the Xiongnu bow, even though the latter were trained to shoot behind themselves while riding.[17]

Islamic World

The Saracens called the crossbow qaws Ferengi, or "Frankish bow", as the Crusaders used the crossbow against the Arab and Turkoman horsemen with remarkable success. The adapted crossbow was used by the Islamic armies in defence of their castles. Later footstrapped version become very popular among the Muslim armies in Spain. During the Crusades, Europeans were exposed to Saracen composite bows, made from layers of different material—often wood, horn and sinew—glued together and bound with animal tendon. These composite bows could be much more powerful than wooden bows, and were adopted for crossbow prods across Europe.

Africa and in the Americas

In Western Africa crossbows served as a scout weapon and for hunting, with enslaved Africans bringing the technology to America.[10] In the American south, the crossbow was used for hunting when firearms or gunpowder were unavailable because of economic hardships or isolation.[10] Light hunting crossbows were traditionally used by the Inuit in Northern America.

Use of crossbows today

Crossbows are mostly used for target shooting in modern archery.

In some countries they are still used for hunting, such as in a few states within the USA, parts of Asia and Australia or Africa. Other uses with special projectiles are in whale research to take blubber biopsy samples without harming the whales. [18]

Active military and police usage

-

Peruvian soldiers equipped with recurve crossbows and ropes.

-

Serbian special forces demonstrating a crossbow to the Minister of Defence.

-

Chinese PLA soldier training with crossbow, alongside firearms.

In the Americas, the Peruvian army (Ejército) equips some soldiers with crossbows and rope, to establish a zip-line in difficult terrain.[19] In Brazil the CIGS (Jungle Warfare Training Center) also trains soldiers in the use of crossbows.[20][21]

In Europe, British based Barnett International supplied crossbows to Serbian forces which were later used in ambush and anti-sniper operations against the Kosovo Liberation Army during the Kosovo War[22]. Whitehall launched an investigation, though the department of trade and industry established that not being "on the military list" crossbows were not covered by such export regulations. Paul Beaver of Jane's defence publications commented that, "They are not only a silent killer, they also have a psychological effect". On February 15 2008 Serbian Minister of Defence Dragan Sutanovac was pictured testing a Barnett crossbow during a public exercise of the Serbian army's Special Forces in Nis, 200km south of capital Belgrade.[23] Special forces in both Greece and Turkey also continue to employ the crossbow.[24][25]

In Asia, Chinese armed forces use crossbows at all unit levels from traffic police to the special forces units of the People's Liberation Army.[26][27][28]

See also

References

- ^ Gurstelle, William (2004).The Art of the Catapult. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1-5565-2526-5, p. 49

- ^ Brodie, Bernard and Fawn McKay Brodie. (1973). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253201616. Pages 20 & 35.

- ^ a b DeVries, Kelly Robert. (2003). Medieval Military Technology. Petersborough: Broadview Press. ISBN 0921149743. Page 127.

- ^ DeVries, Kelly Robert. (2003). Medieval Military Technology. Petersborough: Broadview Press. ISBN 0921149743. Page 128.

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, Sarah B. Pomeroy, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts (1999). Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1950-9742-4, p. 366

- ^ John Warry, Warfare in the Classical World, p. 79

- ^ Duncan B Campbell, Ancient Siege Warfare 2005 Osprey Publishing ISBN 1-84176-770-0, p. 26-56

- ^ John Warry, Warfare in the Classical World,University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2794, p.90

- ^ a b Verbruggen, J.F (1997). The art of warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Boydell&Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-570-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Notes On West African Crossbow Technology

- ^ Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol 5 Part 6. Cambridge University Press. pp. p. 135. ISBN 0521087325.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Liang, Jieming (2006). Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity ISBN 981-05-5380-3, pp. Appendix D

- ^ James Clavell, The Art of War, prelude

- ^ http://www.gutenberg.org/files/132/132.txt

- ^ Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China: Second Impression, With Corrections. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 9004096329. Pages 153, 157–158.

- ^ Weapons of the terracotta army

- ^ Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521770645. Page 203.

- ^ The St. Lawrence

- ^ Ejercito prepare for deployment.

- ^ CIGS information thread.

- ^ CIGS photograph.

- ^ The Guardian.

- ^ Day Life Serbia report

- ^ Greek soldiers uses crossbow.

- ^ Turkish special ops.

- ^ Chinese news report on crossbows.

- ^ Chinese traffic police using crossbows.

- ^ Chinese special forces with crossbows.