Electron

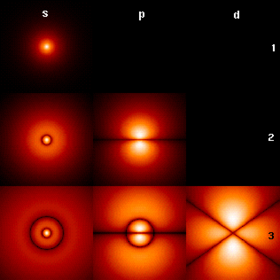

Theoretical estimates of the electron density for the first few hydrogen atom electron orbitals shown as cross-sections with color-coded probability density | |

| Composition | Elementary particle |

|---|---|

| Family | LeptonFermion |

| Generation | First |

| Interactions | Gravity, Electromagnetic, Weak |

| Symbol | e−, β− |

| Antiparticle | Positron |

| Theorized | G. Johnstone Stoney (1874) |

| Discovered | J.J. Thomson (1897) |

| Mass | 9.109 382 15(45) × 10–31 kg[1]

5.485 799 09(27) × 10–4 u 1⁄1822.888 4843(11) u 0.510 998 918(44) MeV/c2 |

| Electric charge | –1.602 176 487(40) × 10–19 C[2] |

| Magnetic moment | 1.0011596521859(38) μB |

| Spin | ½ |

The electron is a fundamental subatomic particle that carries a negative electric charge. It is a spin ½ lepton that participates in electromagnetic interactions, and its mass is approximately of that of the proton. Together with atomic nuclei, which consist of protons and neutrons, electrons make up atoms. The electron(s) interaction with electron(s) of adjacent nuclei is the main cause of chemical bonding.

History

The name electron comes from the Greek word for amber, ἤλεκτρον. This material played an essential role in the discovery of electrical phenomena. The ancient Greeks knew, for example, that rubbing a piece of amber with fur left an electric charge on its surface, which could then create a spark when brought close to a grounded object.

The electron as a unit of charge in electrochemistry was posited by G. Johnstone Stoney in 1874, who also coined the term electron in 1894.

In this paper an estimate was made of the actual amount of this most remarkable fundamental unit of electricity, for which I have since ventured to suggest the name electron.

— Stoney, George Johnstone (1894). "Of the "Electron," or Atom of Electricity". Philosophical Magazine. 38 (5): 418–420.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

During the late 1890s a number of physicists proposed that electricity, as observed in studies of electrical conduction in conductors, electrolytes, and cathode ray tubes, consisted of discrete units, which were given a variety of names, but the reality of these units had not been confirmed in a compelling way. However, there were also indications that the cathode rays had wavelike properties. In 1896 J.J. Thomson performed experiments indicating that cathode rays really were particles, found an accurate value for their charge-to-mass ratio e/m, and found that e/m was independent of cathode material. He made good estimates of both the charge e and the mass m, finding that cathode ray particles, which he called "corpuscles", had perhaps one thousandth of the mass of the least massive ion known (hydrogen). He further showed that the negatively charged particles produced by radioactive materials, by heated materials, and by illuminated materials, were universal.

Thomson's 1906 Nobel Prize lecture can be found at http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1906/thomson-lecture.html. He notes that prior to his work: (1) the (negatively charged) cathode was known to be the source of the cathode rays; (2) the cathode rays were known to have the particle-like property of charge; (3) were deflected by a magnetic field like a negatively charged particle; (4) had the wave-like property of being able to penetrate thin metal foils; (5) had not yet been subject to deflection by an electric field.

Thomson succeeded in causing electric deflection because his cathode ray tubes were sufficiently evacuated that they developed only a low density of ions (produced by collisions of the cathode rays with the gas remaining in the tube). Their ion densities were low enough that the gas was a poor conductor, unlike the tubes of previous workers, where the ion density was high enough that the ions could screen out the electric field. He found that the cathode rays (which he called corpuscles) were deflected by an electric field in the same direction as negatively charged particles would deflect. With the electrons moving along, say, the x-direction, the electric field E pointing along the y-direction, and the magnetic field B pointing along the z-direction, by adjusting the ratio of the magnetic field B to the electric field E he found that the cathode rays moved in a nearly straight line, an indication of a nearly uniform velocity v=E/B for the cathode rays emitted by the cathode. He then removed the magnetic field and measured the deflection of the cathode rays, and from this determined the charge-to-mass ratio e/m for the cathode rays. He writes: "however the cathode rays are produced, we always get the same value of e/m for all the particles in the rays. We may...produce great changes in the velocity of the particles, but unless the velocity of the particles becomes so great that they are moving nearly as fast as light, when other considerations have to be taken into account, the value of e/m is constant. The value of e/m is not merely independent of the velocity...it is independent of the kind of electrodes we use and also of the kind of gas in the tube."

Thomson notes that "corpuscles" are emitted by hot metals and "Corpuscles are also given out by metals and other bodies, but especially by the alkali metals, when these are exposed to light. They are being continually given out in large quantities and with very great velocities by radioactive substances such as uranium and radium; they are produced in large quantities when salts are put into flames, and there is good reason to suppose that corpuscles reach us from the sun." Thomson also describes water drop experiments that enabled him to obtain a value for e that is about twice the modern value, and close to the then current value for the charge on a hydrogen ion in an electrolyte. The electron's charge shortly was more carefully measured by R. A. Millikan in his oil-drop experiment of 1909. Oil drops, not subject to evaporation, were more stable than water drops and more suited to precise experimentation over longer periods of time.

The periodic law states that the chemical properties of elements largely repeat themselves periodically and is the foundation of the periodic table of elements. The law itself was initially explained by the atomic mass of the element. However, as there were anomalies in the periodic table, efforts were made to find a better explanation for it. In 1913, Henry Moseley introduced the concept of the atomic number and explained the periodic law in terms of the number of protons each element has. In the same year, Niels Bohr showed that electrons are the actual foundation of the table. In 1916, Gilbert Newton Lewis explained the chemical bonding of elements by electronic interactions.

Classification

The electron is in the class of subatomic particles called leptons, which are believed to be fundamental particles.

As with all particles, electrons can also act as waves. This is called the wave-particle duality, also known by the term complementarity coined by Niels Bohr, and can be demonstrated using the double-slit experiment.

The antiparticle of an electron is the positron, which has positive rather than negative charge. The discoverer of the positron, Carl D. Anderson, proposed calling standard electrons negatrons, and using electron as a generic term to describe both the positively and negatively charged variants. This usage of the term "negatron" is still occasionally encountered today, and it may also be shortened to "negaton".[3]

Properties and behavior

Electrons have an electric charge of −1.602 × 10−19 C, a mass of 9.11 × 10−31 kg based on charge/mass measurements equivalent to a rest mass of about 0.511 MeV/c². The mass of the electron is approximately 1/1836 of the mass of the proton. The common electron symbol is e−.[1] The electron is thought to be stable on theoretical grounds; the lowest known experimental upper bound for its mean lifetime is 4.6×1026 years, with a 90% confidence interval (see Particle decay).

According to quantum mechanics, electrons can be represented by wavefunctions, from which a calculated probabilistic electron density can be determined. The orbital of each electron in an atom can be described by a wavefunction. Based on the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the exact momentum and position of the actual electron cannot be simultaneously determined. This is a limitation which, in this instance, simply states that the more accurately we know a particle's position, the less accurately we can know its momentum, and vice versa.

The electron has spin ½ and is a fermion (it follows Fermi-Dirac statistics). In addition to its intrinsic angular momentum, an electron has an intrinsic magnetic moment along its spin axis.

Electrons in an atom are bound to that atom, while electrons moving freely in vacuum, space or certain media are free electrons that can be focused into an electron beam. When free electrons move, there is a net flow of charge, and this flow is called an electric current. The drift velocity of electrons in metal wires is on the order of millimetres per second. However, the speed at which a current at one point in a wire causes a current in other parts of the wire, the velocity of propagation, is typically 75% of light speed.

In some superconductors, pairs of electrons move as Cooper pairs in which their motion is coupled to nearby matter via lattice vibrations called phonons. The distance of separation between Cooper pairs is roughly 100 nm.

A body has an electric charge when that body has more or fewer electrons than are required to balance the positive charge of the nuclei. When there is an excess of electrons, the object is said to be negatively charged. When there are fewer electrons than protons, the object is said to be positively charged. When the number of electrons and the number of protons are equal, their charges cancel each other and the object is said to be electrically neutral. A macroscopic body can develop an electric charge through rubbing, by the phenomenon of triboelectricity.

When electrons and positrons collide, they annihilate each other and produce pairs of high-energy photons or other particles. On the other hand, high-energy photons may transform into an electron and a positron by a process called pair production, but only in the presence of a nearby charged particle, such as a nucleus.

The electron is currently described as a fundamental or elementary particle. It has no known substructure. Hence, for convenience, it is usually defined or assumed to be a point-like mathematical point charge, with no spatial extension. However, when a test particle is forced to approach an electron, we measure changes in its properties (charge and mass). This effect is common to all elementary particles. Current theory suggests that this effect is due to the influence of vacuum fluctuations in its local space, so that the properties measured from a significant distance are considered to be the sum of the bare properties and the vacuum effects (see renormalization).

The "classical electron radius" is 2.8179 × 10−15 m. This is the radius that is inferred from the electron's electric charge, by using the classical theory of electrodynamics alone, ignoring quantum mechanics. (In modern physics, the electron is believed to be a point particle, thus its actual radius is zero.) Classical electrodynamics (Maxwell's electrodynamics) is the older concept that is widely used for practical applications of electricity, electrical engineering, semiconductor physics, and electromagnetics. Quantum electrodynamics, on the other hand, is useful for applications involving modern particle physics and some aspects of optical, laser and quantum physics.

Based on current theory, the speed of an electron can approach, but never reach, c (the speed of light in a vacuum). This limitation is attributed to Einstein's theory of special relativity which defines the speed of light as a constant within all inertial frames. However, when relativistic electrons are injected into a dielectric medium such as water, where the local speed of light is significantly less than c, the electrons (temporarily) travel faster than light in the medium. As they interact with the medium, they generate a faint bluish light called Cherenkov radiation.

The effects of special relativity are based on a quantity known as γ or the Lorentz factor. γ is a function of v, the coordinate velocity of the particle. It is defined as:

The kinetic energy of an electron (moving with velocity v) is:

For example, the Stanford linear accelerator can accelerate an electron to roughly 51 GeV [1]. This gives a gamma of 100,000, since the mass of an electron is 0.51 MeV/c² (the relativistic momentum of this electron is 100,000 times the classical momentum of an electron at the same speed). Solving the equation above for the speed of the electron (and using an approximation for large γ) gives:

The de Broglie wavelength of a particle is λ=h/p where h is Planck's constant and p is momentum. At low (e.g photoelectron) energies this determines the size of atoms, and at high (e.g. electron microscope) energies this makes the Bragg angles for electron diffraction (co-discovered by J. J. Thomson's son G. P. Thomson) well under one degree. Since momentum is mass times proper-velocity w=γv, we have

For the 51 GeV electron above, proper-velocity is approximately γc, making the wavelength of those electrons small enough to explore structures well below the size of an atomic nucleus.

Visualisation

The first video images of an electron were captured by a team at Lund University in Sweden in February 2008. To capture this event, the scientists used extremely short flashes of light. To produce this light, newly developed technology for generating short pulses from intense laser light, called attosecond pulses, allowed the team at the university’s Faculty of Engineering to capture the electron's motion for the first time.

"It takes about 150 attoseconds for an electron to circle the nucleus of an atom. An attosecond is related to a second as a second is related to the age of the universe," explained Johan Mauritsson, an assistant professor in atomic physics at the Faculty of Engineering, Lund University.[4][5]

The distribution of the electrons in the reciprocal space of solids can be visualized by angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy.

Electrons in chemistry

In 1913, Niels Bohr showed that electrons are the actual foundation of the periodic table of chemical elements, and, in 1916, Gilbert Newton Lewis explained the chemical bonding of elements by electronic interactions. From these discoveries it has become clear that electrons, in particular those orbiting on the outer shell of the atom, play a fundamental part in chemical structure and chemical interactions, and that these interactions form the central part of chemistry, without which it could not even exist.

In practice

In the universe

Scientists believe that the number of electrons existing in the known universe is at least 1079. This number amounts to an average density of about one electron per cubic metre of space. Astronomers have estimated that 90% of the mass of atoms in the universe is hydrogen, which is made of one electron and one proton.

In industry

Electron beams are used in welding, lithography, scanning electron microscopes and transmission electron microscopes. LEED and RHEED are surface-imaging techniques that use electrons.

Electrons are also at the heart of cathode ray tubes, which are used extensively as display devices in laboratory instruments, computer monitors and television sets. In a photomultiplier tube, one photon strikes the photocathode, initiating an avalanche of electrons that produces a detectable current.

In the laboratory

The uniquely high charge-to-mass ratio of electrons means that they interact strongly with atoms, and are easy to accelerate and focus with electric and magnetic fields. Hence some of today's aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopes use 300keV electrons with velocities greater than the speed light travels in water (approximagely 1/2 to 2/3 of c), wavelengths below 2 picometers, transverse coherence-widths over a nanometer, and longitudinal coherence-widths 100 times that. This allows such microscopes to image scattering from individual atomic-nuclei (HAADF) as well as interference-contrast from solid-specimen exit-surface deBroglie-phase (HRTEM) with lateral point-resolutions down to 60 picometers. Magnifications approaching 100 million are needed to make the resulting image detail comfortably visible to the naked eye.

Quantum effects of electrons are also used in the scanning tunneling microscope to study features on solid surfaces with lateral-resolution at the atomic scale (around 200 picometers) and vertical-resolutions much better than that. In such microscopes, the quantum tunneling is strongly dependent on tip-specimen separation, and, precise control of the separation (vertical sensitivity) is made possible with a piezoelectric scanner.

In medicine

In radiation therapy, electron beams are used for treatment of superficial tumours.

In theory

In Dirac's model, an electron is defined to be a mathematical point, a point-like, charged "bare" particle surrounded by a sea of interacting pairs of virtual particles and antiparticles. These provide a correction of just over 0.1% to the predicted value of the electron's gyromagnetic ratio from exactly 2 (as predicted by Dirac's single-particle model). The extraordinarily precise agreement of this prediction with the experimentally determined value is viewed as one of the great achievements of modern physics.[6]

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the electron is the first-generation charged lepton. It forms a weak isospin doublet with the electron neutrino; these two particles interact with each other through both the charged and neutral current weak interaction. The electron is very similar to the two more massive particles of higher generations, the muon and the tau lepton, which are identical in charge, spin, and interaction, but differ in mass.

The antimatter counterpart of the electron is the positron. The positron has the same amount of electrical charge as the electron, except that the charge is positive. It has the same mass and spin as the electron. When an electron and a positron meet, they may annihilate each other, giving rise to two gamma-ray photons emitted at roughly 180° to each other. If the electron and positron had negligible momentum, each gamma ray will have an energy of 0.511 MeV. See also Electron-positron annihilation.

Electrons are a key element in electromagnetism, a theory that is accurate for macroscopic systems, and for classical modelling of microscopic systems.

Notes

- ^ a b All masses are 2006 CODATA values accessed via the NIST’s electron mass page. The fractional version’s denominator is the inverse of the decimal value (along with its relative standard uncertainty of 5.0 × 10–8)

- ^ The electron’s charge is the negative of elementary charge (which is a positive value for the proton). CODATA value accessed via the NIST’s elementary charge page.

- ^ Schweber, Silvan S. (2005) [1962]. An Introduction to Relativistic Quantum Field Theory (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-44228-4.

- ^ http://www.atto.fysik.lth.se/ Lund Univ with video link

- ^ http://www.atto.fysik.lth.se/video/pressrelen.pdf Lund Univ. Press release

- ^ *Griffiths, David J. (2004). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

See also

- Electron bubble

- Elementary charge

- Exoelectron

- One-electron universe

- Pair production

- Positron

- Proton

- Covalent bonding

- Atom

External links

- The NIST’s latest CODATA value for electron mass

- The Discovery of the Electron from the American Institute of Physics History Center

- Particle Data Group

- Stoney, G. Johnstone, "Of the 'Electron,' or Atom of Electricity". Philosophical Magazine. Series 5, Volume 38, p. 418-420 October 1894.

- Eric Weisstein's World of Physics: Electron

- Researchers Catch Motion of a Single Electron on Video A FIRST COURSE IN PHYSICS by Robert A. Milliken PhD and Henry G Gale PhD Ginn & Co. 1906