Transcendental Meditation

Transcendental Meditation (TM) refers to the Transcendental Meditation technique,[1] a specific form of mantra meditation, and to the Transcendental Meditation movement, a spiritual movement.[2][3] The TM technique and TM movement were introduced in India in the mid-1950s by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1914–2008) and had reached global proportions by the 1960s.

The TM technique came out of and is based on Indian philosophy and the teachings of Krishna, the Buddha, and Shankara, as well as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali,[4] and is a version of a technique passed down from the Maharishi's teacher, Brahmananda Saraswati. The Maharishi also developed the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI), a system of theoretical principles to underlie this meditation technique. Additional technologies were added to the Transcendental Meditation program, including "advanced techniques" such as the TM-Sidhi program (Yogic Flying).

TM is one of the most widely practiced, and among the most widely researched meditation techniques.[5][6][7][8] Independent[9] systematic reviews have not found health benefits for TM beyond relaxation or health education.[10][11][12] Skeptics have called TM or its associated theories and technologies a pseudoscience.[13][14][15]

In the 1950s, the Transcendental Meditation movement was presented as a religious organization. The Transcendental Meditation technique was held to be a religion in a New Jersey court case.[16][17] By the 1970s, the organization had shifted to a more scientific presentation while maintaining many religious elements.[4] The movement now describes itself on a spiritual, scientific, and non-religious basis. This shift has been described by both those within and outside the movement as an attempt to appeal to the more secular West.[4]

The TM movement has programs and holdings in multiple countries while as many as six million people have been trained in the TM technique, including The Beatles, Russell Brand, and other well-known public figures.

History

The history of modern Transcendental Meditation began in the late 1950s, when Maharishi Mahesh Yogi first taught the technique, and continues beyond 2008, the year of the Maharishi's death.

Although he had already initiated thousands of people, the Maharishi began a program to create more teachers of the technique as a way to accelerate the rate of creating new meditators. The Maharishi began a series of world tours which promoted the technique, and this, the celebrities who practiced the technique, and later scientific research endorsing the technique helped to popularize the technique in the 1960s and '70s. In the 1970s, advanced meditation techniques were introduced. By the late 2000s, TM had been taught to millions of individuals and the Maharishi was overseeing a large multinational movement. The movement has grown to encompass schools and universities that teach the practice, and includes many associated programs offering health and well-being based on the Maharishi's interpretation of the Vedic traditions.

Among the first organizations to promote TM were the Spiritual Regeneration Movement and the International Meditation Society. In the U.S., major organizations included Student International Meditation Society, World Peace Executive Council, Maharishi Vedic Education Corporation, and Global Country of World Peace. The successor to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and head of the Global Country of World Peace, is Tony Nader (Maharaja Adhiraj Rajaraam).

While additional techniques were added, and the organization that taught the Transcendental Meditation and additional techniques changed, the TM technique itself remained relatively unchanged.

According to religious scholar Kenneth Boa in his 1990 book, Cults, World Religions and the Occult, the Transcendental Meditation technique is rooted in the Vedantic School of Hinduism, "repeatedly confirmed" in books authored by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi such as the Science of Being and the Art of Living and Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita.[18] Boa writes that the Maharishi "makes it clear" that Transcendental Meditation was delivered to man about 5,000 years ago by the Hindu god Krishna. The technique was then lost, but restored for a time by Buddha. It was lost again, but rediscovered in the 9th century AD by the Hindu philosopher Shankara. Finally, it was revived by Brahmananda Saraswati (Guru Dev) and passed on to the Maharishi.[19]

George Chryssides similarly says, in his 1999 book, Exploring New Religions, that the Maharishi and Guru Dev were from the Shankara tradition of advaita Vedanta.[20] Peter Russell, in his 1976 book The TM Technique, says that the Maharishi believed that from the time of the Vedas, this knowledge cycled from lost to found multiple times, as is described in the introduction of the Maharishi's commentaries on the Bhagavad-Gita. Revival of the knowledge recurred principally in the Bhagavad-Gita, and in the teachings of Buddha and Shankara.[21] Chryssides notes that, in addition to the revivals of the Transcendental Meditaton technique by Krishna, the Buddha and Shankara, the Maharishi also drew from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[20] Bromley also says the technique is based on Indian philosophy and the teachings of Krishna, the Buddha, and Shankara.[4] In a chapter of a 1998 book titled Alternative medicine and ethics, Vimal Patel writes that the Maharishi drew from Patanjali when developing the TM technique.[22]

While the Transcendental Meditation technique was originally presented in religious terms during the 1950s, this changed to an emphasis on scientific verification in the 1970s; attributed to an effort to improve its public relations, and as an attempt to bring the teaching of the TM technique into American public schools where church and state are separated.[23][24]

Technique

The Transcendental Meditation technique is a form of mantra meditation that, according to the TM organization, is effortless when used properly. The mantra is a sound that is thought (but not spoken) during meditation.[25] and is utilized as a vehicle that allows the individual's attention to travel naturally to a less active, quieter style of mental functioning.[25][26] The technique is practiced morning and evening for 15–20 minutes each time.[27][28]

The mantras are generally considered to be sounds without meaning,[26][29] though some have claimed that they refer to deities.[30][31] Mantras are said to be selected by trained teachers to suit the individual. Students are told to never share their mantras with anyone.[32] Scholars say that the original mantras derive from the Vedic or Tantric tradition.[33][34] The Maharishi is said to have reduced the number of mantras used from hundreds down to a minimum number.[35] Some reports say that the total number of mantras used is 16, and that they are assigned using a simple formula based on gender and age.[36][37][38]

Some claim that the trademarked Transcendental Meditation technique can be learned only from a certified teacher.[21][39] The Transcendental Meditation technique is taught during a standardized seven-step course consisting of two introductory lectures, a personal interview, and four two-hour long instruction sessions given on consecutive days.[28][40] The initial personal instruction session begins with a short puja ceremony performed by the teacher, after which the student is taught the technique.[41] Following initiation the student practices the technique twice a day. During subsequent group sessions the teacher gives the student feedback so that they know they're practicing TM correctly. During step five the teacher again corrects the student and provides him/her further instruction; during step six the teacher tells the student the mechanics of the TM technique based on his/her personal experiences; and in step seven the teacher explains the higher stages of human development that the TM organization say can be achieved through the TM technique.[42] As stated by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1955 in The Beacon Light of the Himalayas he said: "For purpose we select only the suitable mantras of personal gods. Such mantras fetch to us the grace of personal gods and make us happier in every walk of life".[43]

The fee charged for instruction has varied over time and also by country. In the 1960s, in the United States, the usual fee was one-week's salary or $35 for a student.[44][45][46] In the 1970s, it became a fixed fee of $125 in America with discounts for students and families.[47] By 2003, the fee in the United States was set at $2,500.[48] It has since been reduced to $1,500.[49][50] Advanced techniques[51] and rounding sessions require additional fees.[citation needed] In 2011, the fees for learning TM in Great Britain vary from £190.00 to £590.00 depending on income.[52]

"Rounding" is a combination of yogic breathing techniques, yoga postures or asanas, and meditation, repeated for a prolonged period in a supervised setting.[53][54] There are other "advanced techniques" that build on the basic TM technique. Using TM-Sidhi, the most prominent of these, practitioners are said to achieve "Yogic Flying".[36][55][56]

The Maharishi predicted that the quality of life for an entire population would be noticeably improved if one percent (1%) of the population practiced the Transcendental Meditation technique. This is known as the "Maharishi Effect".[57]

The US District Court of New Jersey, in 1977, in Docket # 76-341, considered the TM technique to be religious in nature, and did not allow it in schools in New Jersey.[58]

Movement

The Transcendental Meditation movement (also referred to as Transcendental Meditation (TM), "Maharishi's worldwide movement", and the Transcendental Meditation Organization) is a world-wide organization founded by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the 1950s. Estimated to have tens of thousands of participants, with high estimates citing as many as several million,[59] the global organization also consists of close to 1,000 TM centers, and controls property assets of the order of USD 3.5 billion (1998 estimate).[60]

It includes programs and organizations connected to the Transcendental Meditation technique, developed and or introduced by the founder. An advanced form of meditation is the TM-Sidhi program which includes "Yogic flying". Maharishi Ayurveda is a system of health treatments using herbs and massage. Maharishi Sthapatya Veda is a system of architecture and city planning.

The first organization was the Spiritual Regeneration Movement, founded in India in 1958. The International Meditation Society and Student International Meditation Society (SIMS) were founded in the US in the 1960s. The organizations were consolidated under the leadership of the World Plan Executive Council in the 1970s. In 1992, a political party, the Natural Law Party (NLP) was founded based on the principles of TM and it ran candidates in ten countries before disbanding in 2004.[4] The Global Country of World Peace is the current main organization. The movement operates numerous schools and universities. Mother Divine and Thousand-Headed Purusha are the monastic arms. It also has health spas and assorted businesses. There are many TM-centered communities.

The TM movement has been described as a spiritual movement, as a new religious movement, and a "Neo-Hindu" sect.[61] It has been characterized as a religion, a cult, a charismatic movement, a "sect", "plastic export Hinduism", a progressive millennialism organization and a "multinational, capitalist, Vedantic Export Religion" in books and the mainstream press,[61][62] with concerns that the movement was being run to promote the Maharishi's personal interests.[63] Other sources assert that TM is not a religion, but a meditation technique; and they hold that the TM movement is a spiritual organization, and not a religion or a cult.[64][65] Participation in TM programs at any level does not require one to hold or deny any specific religious beliefs; TM is practiced by people of many diverse religious affiliations, as well as atheists and agnostics.[66][67][68]

Research

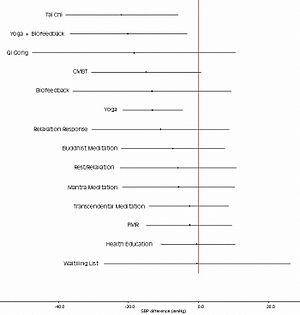

Independent systematic reviews have not found health benefits for TM beyond relaxation and health education.[12][70][71] It is difficult to determine definitive effects of meditation practices in healthcare, as the quality of research has design limitations and a lack of methodological rigor.[12][72][73] Part of this difficulty is because studies have the potential for bias due to the connection of researchers to the TM organization, and enrollment of subjects with a favorable opinion of TM.[74][75]

There has been ongoing research on Transcendental Meditation since the first studies were conducted at the UCLA and Harvard University were published in Science and the American Journal of Physiology in 1970 and 1971.[76] The research has included studies on physiological changes during meditation, clinical applications, cognitive effects, mental health, addiction, and rehabilitation. Beginning in the 1990s, a focus of research has been the effects of Transcendental Meditation on cardiovascular disease, with over $20 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health.[77]

References

- ^ "Transcendental Meditation". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "Transcendental Meditation – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Dalton, Rex (July 8, 1993). "Sharp HealthCare announces an unorthodox, holistic institute". The San Diego Union – Tribune. p. B.4.5.1.

TM is a movement led by Maharishi Mehesh Yogi,....

- ^ a b c d e Bromley, David G.; Cowan, Douglas E. (2007). Cults and New Religions: A Brief History (Blackwell Brief Histories of Religion). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 48–71. ISBN 1-4051-6128-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Murphy M, Donovan S, Taylor E. The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation: A review of Contemporary Research with a Comprehensive Bibliography 1931–1996. Sausalito, California: Institute of Noetic Sciences; 1997.

- ^ Benson, Herbert; Klipper, Miriam Z. (2001). The relaxation response. New York, NY: Quill. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-380-81595-1.

- ^ Sinatra, Stephen T.; Roberts, James C.; Zucker, Martin (December 20, 2007). Reverse Heart Disease Now: Stop Deadly Cardiovascular Plaque Before It's Too Late. Wiley. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-470-22878-4.

- ^ Travis, Frederick; Chawkin, Ken (Sept–Oct, 2003). New Life magazine.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Methods Co-ordinator | The Cochrane Collaboration". Cochrane Collabortion.

The Cochrane Collaboration is an independent, not-for-profit, research organisation

- ^ Ospina MB, Bond TK, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Liang Y, Bialy L, Hooton N, Buscemi N, Dryden DM, Klassen TP. (June 2007). Meditation Practices for Health: State of the Research (PDF). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. p. 4.

A few studies of overall poor methodological quality were available for each comparison in the meta-analyses, most of which reported nonsignificant results. TM had no advantage over health education to improve measures of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, body weight, heart rate, stress, anger, self-efficacy, cholesterol, dietary intake, and level of physical activity in hypertensive patients

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, Piyavhatkul N (2010). Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai (ed.). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMID 20556767.

As a result of the limited number of included studies, the small sample sizes and the high risk of bias, we are unable to draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation therapy for ADHD.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M (2006). Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai (ed.). "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

The small number of studies included in this review do not permit any conclusions to be drawn on the effectiveness of meditation therapy for anxiety disorders. Transcendental meditation is comparable with other kinds of relaxation therapies in reducing anxiety

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Cochrane06" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "James Randi Educational Foundation — An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural".

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1997). The demon-haunted world: science as a candle in the dark. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-345-40946-9.

- ^

- Boa, Kenneth, Cults, World Religions and the Occult, David C. Cook, 1990 ISBN 0896938239, 9780896938236 p. 204

- Carlson, Ron, Decker, Ed, Fast Facts on False Teachings Harvest House Publishers, 2003 ISBN 0736912142, 9780736912143 p. 254

- Hexham, Irving, Pocket Dictionary of New Religious Movements, InterVarsity Press, 2002 ISBN 0830814663, 9780830814664 p. 74

- Marvizon, Juan Carlos "Meditation", Shermer, Michael (ed)The Skeptic: Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience ABC-CLIO, 2002 ISBN 1576076539, 9781576076538 p 141

- Nanda, Meera "Postmodernism, Hindu Nationalism and Vedic Science", Koertge, Noretta Scientific Values and Civic Virtues, Oxford University Press US, 2005 ISBN 0195172256, 9780195172256 p 232

- Kinman, John M., Of One Mind:The Collectivization of Science Springer, 1995 ISBN 1563960656, 9781563960659 p 130

- Hook, Ernest B, Prematurity in Scientific Discovery; On Resistance and Neglect University of California Press, 2002 ISBN 0520231066, 9780520231061 p 215

- Becker, Carl B. Paranormal Experience and Survival of Death, SUNY Press, 1993 ISBN 0791414752, 9780791414750 p 1

- Bainbridge, William Sims, Across the Secular Abyss: From Faith to Wisdom Lexington Books, 2007 ISBN 0739116789, 9780739116784 p 10

- Stenger, Victor, Quantum Gods: Creation, Chaos and the Search for Cosmic Consciousness Prometheus Books, 2009 ISBN 1591027136, 9781591027133

- ^ Church-state issues in America today (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Praeger. 2008. p. 159. ISBN 9780275993689.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ American Bar Association (1978). "Constitutional Law... Separating Church and State". ABA Journal. 64: 144.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Boa cites Meditations of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita, and The Science of Being and Art of Living.

- ^ Boa, Kenneth (1990). Cults, world religions, and the occul. Wheaton, Ill.: Victor Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-89693-823-6.

- ^ a b Chryssides, George D. (1999). Exploring new religions. London: Cassell. pp. 293–296. ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6.

- ^ a b Russell, Peter H. (1976). The TM technique. Routledge Kegan Paul PLC. p. 134. ISBN 0-7100-8539-7.

- ^ Patel, Vimal (1998). "Understanding the Integration of Alternative Modalities Into an Emerging Healthcare Model In the United States". In Humber, James M.; Almeder, Robert F. (eds.). Alternative medicine and ethics. Humana Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780896034402.

- ^ Dawson, Lorne L. (2003). Cults and New Religious Movements: A Reader (Blackwell Readings in Religion). Blackwell Publishing Professional. p. 54. ISBN 1-4051-0181-4.

- ^ Chryssides, George D.; Margaret Lucy Wilkins (2006). A reader in new religious movements. London: Continuum. p. 7. ISBN 0-8264-6167-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Phelan, Michael (1979). "Transcendental Meditation. A Revitalization of the American Civil Religion". Archives des sciences sociales des religions. 48 (48–1): 5–20.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Hunt, Stephen (2003). Alternative religions: a sociological introduction. Aldershot, Hampshire, England ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-0-7546-3410-2.

- ^ "Behavior: THE TM CRAZE: 40 Minutes to Bliss". Time. October 13, 1975. ISSN 0040-718X. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ a b Cotton, Dorothy H. G. (1990). Stress management : an integrated approach to therap. New York: Brunner/Mazel. p. 138. ISBN 0-87630-557-5.

- ^ Shear, J. (Jonathan) (2006). The experience of meditation : experts introduce the major tradition. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. pp. 23, 30–32, 43–44. ISBN 978-1-55778-857-3.

- ^ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1955). Beacon Light of the Himalyas (PDF). p. 63.

- ^ Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (2005). Gurus in Americ. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7914-6573-8.

- ^ Oates, Robert M. (1976). Celebrating the dawn: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and the TM technique. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 194. ISBN 9780399118159.

- ^ Russell, pp. 49–50

- ^ Williamson, Lola (2010). Transcendent in America. New York University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780814794500.

- ^ Jefferson, William (1976). The Story of The Maharishi. New York: Pocket (Simon and Schuster). pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Bainbridge, William Sims (1997). The sociology of religious movements. New York: Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 0-415-91202-4.

- ^ "Transcendental Truth". Omni. Jan 1984. p. 129.

- ^ Scott, R.D. (1978). Transcendental Misconceptions. San Diego: Beta Books. ISBN 0892930314.

- ^ "Learn the Transcendental Meditation Technique – Seven Step Program". Tm.org. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ^ Grosswald, Sarina (October 2005). "Oming in on ADHD". Washington Parent.

- ^ Martin, Walter (1980). The New Cults. Vision House Pub. p. 95. ISBN 978-0884490166.

- ^ "How to Learn", Seven Steps Official TM web site

- ^ Beacon Light of the Himalayas, 1955.

- ^ Slee, John (November 4, 1967). "Towards meditation (with the unmistakable fragrance of money)". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. p. 5.

- ^ Souter, Gavin (December 30, 1967). "Sydney 1967: Non-eternal city". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 2.

- ^ Brothers, Joyce (January 27, 1968). "Maharishi is vague on happiness recipe". Milwaukee Journal. p. B1.

- ^ LaMore, George (December 10, 1975). "The Secular Selling of a Religion". The Christian Century. pp. 1133–1137.

- ^ Overton, Penelope (September 15, 2003). "Group promotes meditation therapy in schools". Hartford Courant. p. B1.

- ^ Johnson, Jenna (December 20, 2009). "Colleges Use Meditation". Washington Post.

- ^ Carmiel, Osharat (September 18, 2009). "Wall Street Meditators". Bloomberg.

- ^ "The Advanced Techniques: Developing Bliss Consciousness to Create Heaven on Earth". Maharishi Health Education Center. February 22, 2009. Archived from the original on October 20, 2010.

- ^ Course Fees UK TM web site

- ^ Knopp, Lisa (1998-11). Flight Dreams: A Life in the Midwestern Landscape. University of Iowa Press. p. 167. ISBN 0877456453.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scott, R. D. (1978-02). Transcendental misconceptions. Beta Books. pp. 30–31, 36–37. ISBN 0892930314.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (2005). Gurus in America. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7914-6573-8.

- ^ Williamson (2010) p. 97

- ^ Wager, Gregg (December 11, 1987). "Musicians Spread the Maharishi's Message of Peace". Los Angeles Times. p. 12.

- ^ District of New Jersey Docket # 76-341 HCM Civil Action judgement on Dec. 12, 1977

- ^ "tens of thousands": New Religious Movements (University of Virginia) (1998), citing Melton, J. Gordon, 1993, Encyclopedia of American Religions. 4th ed. Detroit: Gale Research Inc, 945–946. Occhiogrosso, Peter. The Joy of Sects: A Spirited Guide to the World's Religious Traditions. New York: Doubleday (1996); p 66, citing "close to a million" in the USA. The three million estimate appears to originate with The State of Religion Atlas. Simon & Schuster: New York (1993); pg. 35. O'Brien, J. & M. Palmer. The State of Religion Atlas. Simon & Schuster: New York (1993); p. 35. Petersen, William J. Those Curious New Cults in the 80s. New Canaan, Connecticut: Keats Publishing (1982), p 123 claims "more than a million" in the USA and Europe. The Financial Times (8 February 2003) reported that the movement claims to have five million followers, Bickerton, Ian (February 8, 2003). "Bank makes an issue of mystic's mint". Financial Times. London (UK). p. 09.

- ^ "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi". The Times. London (UK). February 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Persinger, Michael A.; Carrey, Normand J.; Suess, Lynn A. (1980). TM and cult mania. North Quincy, Mass.: Christopher Pub. House. ISBN 0-8158-0392-3.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1997). The demon-haunted world: science as a candle in the dark. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-345-40946-9.

- ^ McTaggart, Lynne (July 24, 2003). The Field. HarperCollins. p. 211. ISBN 9780060931179.

- ^ "TM is not a religion and requires no change in belief or lifestyle. Moreover, the TM movement is not a cult."

- ^ The Herald Scotland, April 21, 2007 Meditation-for-old-hippies-or-a-better-way-of-life?

- ^ ["the TM technique does not require adherence to any belief system—there is no dogma or philosophy attached to it, and it does not demand any lifestyle changes other than the practice of it." [1]

- ^ "Its proponents say it is not a religion or a philosophy."The Guardian March 28, 2009 [2]

- ^ "It's used in prisons, large corporations and schools, and it is not considered a religion.” [3] Concord Monitor

- ^ Ospina p. 128, 130

- ^ Ospina, MB.; Bond, K.; Karkhaneh, M.; Tjosvold, L.; Vandermeer, B.; Liang, Y.; Bialy, L.; Hooton, N.; Buscemi, N. (2007). "Meditation practices for health: state of the research" (PDF). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (155): 4. PMID 17764203.

A few studies of overall poor methodological quality were available for each comparison in the meta-analyses, most of which reported nonsignificant results. TM had no advantage over health education to improve measures of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, body weight, heart rate, stress, anger, self-efficacy, cholesterol, dietary intake, and level of physical activity in hypertensive patients

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Krisanaprakornkit, T.; Ngamjarus, C.; Witoonchart, C.; Piyavhatkul, N. (2010). Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai (ed.). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMID 20556767.

As a result of the limited number of included studies, the small sample sizes and the high risk of bias, we are unable to draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation therapy for ADHD.

- ^ Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M; et al. (2007). "Meditation practices for health: state of the research". Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (155): 1–263. PMID 17764203.

Scientific research on meditation practices does not appear to have a common theoretical perspective and is characterized by poor methodological quality. Firm conclusions on the effects of meditation practices in healthcare cannot be drawn based on the available evidence.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, Piyavhatkul N (2010). Krisanaprakornkit, Thawatchai (ed.). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMID 20556767.

As a result of the limited number of included studies, the small sample sizes and the high risk of bias

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canter PH, Ernst E (2004). "Insufficient evidence to conclude whether or not Transcendental Meditation decreases blood pressure: results of a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Journal of Hypertension. 22 (11): 2049–54. doi:10.1097/00004872-200411000-00002. PMID 15480084.

All the randomized clinical trials of TM for the control of blood pressure published to date have important methodological weaknesses and are potentially biased by the affiliation of authors to the TM organization.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Canter PH, Ernst E (2003). "The cumulative effects of Transcendental Meditation on cognitive function--a systematic review of randomised controlled trials". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 115 (21–22): 758–66. doi:10.1007/BF03040500. PMID 14743579.

All 4 positive trials recruited subjects from among people favourably predisposed towards TM, and used passive control procedures … The association observed between positive outcome, subject selection procedure and control procedure suggests that the large positive effects reported in 4 trials result from an expectation effect. The claim that TM has a specific and cumulative effect on cognitive function is not supported by the evidence from randomized controlled trials.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lyn Freeman, Mosby’s Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A Research-Based Approach, Mosby Elsevier, 2009, p. 163

- ^ QUICK, SUSANNE (October 17, 2004). "Delving into alternative care: Non-traditional treatments draw increased interest, research funding". Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee, WI. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

Further reading

- Scholarly

- Bromley, David G.; Cowan, Douglas E. (2007). Cults and New Religions: A Brief History (Blackwell Brief Histories of Religion). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 48–71. ISBN 1-4051-6128-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chryssides, George D.; Margaret Lucy Wilkins (2006). A reader in new religious movements. London: Continuum. p. 7. ISBN 0-8264-6167-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gablinger, Tamar (2010). The Religious Melting Point: On Tolerance, Controversial Religions and the State : The Example of Transcendental Meditation in Germany, Israel and the United States. Language: English. Tectum. pp. 354 pages. ISBN 3828825060.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Persinger, Michael (1980). TM and Cult Mania. Language: English. Christopher Pub House. pp. 198 pages. ISBN 0815803923.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rothstein, Mikael (1996). Belief Transformations: Some Aspects of the Relation Between Science and Religion in Transcendental Meditation (Tm) and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Language: English. Aarhus universitetsforlag. pp. 227 pages. ISBN 8772884215.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Non-scholarly

- Kropinski v. World Plan Executive Council, 853 F, 2d 948, 956 (D.C. Cir, 1988)

- Geoff Gilpin, The Maharishi Effect: A Personal Journey Through the Movement That Transformed American Spirituality, Tarcher-Penguin 2006, ISBN 1-58542-507-9

- Mason, Paul (2005). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: The Biography of the Man Who Gave Transcendental Meditation to the World". Language: English. Evolution Publishing: 335 pages. ISBN 0-9550361-0-0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Other Researches

- Persinger, M.A. "Transcendental Meditation and general meditation are associated with enhanced complex partial epileptic-like signs: evidence for 'cognitive' kindling?" Perceptual and Motor Skills, 1993, 76, 80-82.

- Castillo, R. J. "Depersonalization and Meditation." Psychiatry, 1990, 53, 158-168.

The depersonalization and derealization experiences of novice subjects while meditating by gazing at a blue vase are strikingly similar to the experiences reported by TM meditators.

- Carsello, C. J. and Creaser, J. W. "Does Transcendental Meditation Affect Grades?" Journal of Applied Psychology, 1978, 63, 644-645. No effect upon grades was demonstrated for TM training.

- Pollack, A. A., Weber, M. A., Case, D. B., Laragh, J. H. "Limitations of Transcendental Meditation in the treatment of essential hypertension." The Lancet, January 8, 1977, 71-73. Patients showed no significant change in blood-pressure after a 6 month study.

- Morler, Edward E. "A Preliminary Study of the Effects of Transcendental Meditation on Selected Dimensions of Organization Dynamics." Unpublished doctoral dissertation, 1973. TM may not have immediate measurable effects, and many changes may be due to placebo effect. (Abstract)

- Heide, F.J. and Borkovec, T.D. "Relaxation-Induced Anxiety: Mechanism and Theoretical Implications." Behavioral Research Therapy, 1984, 22, 1-12.

- A.P. French, A.C. Schmid, and E. Ingalls, "Transcendental Meditation, Altered Reality Testing, and Behavioral Change: A Case Report," Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1975, 161, 55-58.

- R.B. Kennedy, "Self-Induced Depersonalization Syndrome," American Journal of Psychiatry, 1976, 133, 1326-1328.

- A.A. Lazarus, "Psychiatric Problems Precipitated by Transcendental Meditation," Psychological Reports, 1976, 39, 601-602.

- L.S. Otis, "Adverse Effects of Transcendental Meditation," in D. Shapiro and R. Walsh (eds.), Meditation: Classic and Contemporary Perspectives (New York: Alden, 1984).

- M.A. Persinger, "Enhanced Incidence of 'The Sensed Presence' in People Who Have Learned to Meditate: Support for the Right Hemispheric Intrusion Hypothesis," Perceptual and Motor Skills, 1992, 75, 1308-1310.

- J. Younger, W. Adriance, and R.J. Berger, "Sleep during Transcendental Meditation," Perceptual and Motor Skills, 1976,40,953-954.

- D.L. Schacter, "EEG Theta Waves and Psychological Phenomena: A Review and Analysis."Biological Psychology, 5, 1977, 47-82.

- Andrew Skolnick, "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Guru's Marketing Scheme Promises the World Eternal 'Perfect Health'!", JAMA 1991;266:1741-1750,October 2, 1991.

- James Hassett, "Caution: Meditation Can Hurt," Psychology Today, November 1978, 125-126.

TM and Cult Mania by Michael Persinger with Normand J. Carrey and Lynn A. Suess. ISBN 0-8158-0392-3

- By the movement

- Denniston, Denise, The TM Book, Fairfield Press, Fairfield, Iowa, 1986 ISBN 0-931783-02-X

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita : A New Translation and Commentary, Chapters 1–6. ISBN 0-14-019247-6.

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Science of Being and Art of Living : Transcendental Meditation ISBN 0-452-28266-7.

External links

- Official TM site

- A look at four psychology fads — a comparison of est, primal therapy, Transcendental Meditation and lucid dreaming at the Los Angeles Times