Economic freedom: Difference between revisions

m robot Adding: ca:Llibertat econòmica |

Vision Thing (talk | contribs) →Further reading: rm per WP:EL |

||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

*[[Ludwig von Mises]], ''[http://www.mises.org/efandi.asp Economic Freedom and Interventionism] '' |

*[[Ludwig von Mises]], ''[http://www.mises.org/efandi.asp Economic Freedom and Interventionism] '' |

||

*[[Amartya Sen]], ''[[Development as Freedom]]'' |

*[[Amartya Sen]], ''[[Development as Freedom]]'' |

||

*[[http://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2005/0305miller.html Free, Free at Last]] by economist John Miller in [[Dollars & Sense]] magazine |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 13:21, 12 October 2008

Economic freedom is freedom to produce, trade and consume any goods and services acquired without the use of force, fraud or theft. Economic freedom is embodied in the rule of law, property rights and freedom of contract, and characterized by external and internal openness of the markets, the protection of property rights and freedom of economic initiative.[1][2] In the present the concept, as it is most used, is usually associated with a free market system.

Indices of economic freedom try to measure economic freedom, and empirical studies based on some these rankings have found it to be correlated with economic growth and poverty reduction.[3][4]

Institutions of economic freedom

Rule of law

One of the prerequisites for economic freedom is the rule of law; fundamentally, the government must be ruled by the law and be subject to it.[6] The rule of law requires the existence of widely shared cultural values and ethical norms; in the absence of a widespread social concept of justice, the state, or people in power, can violate the rights of citizens, sometimes by turning one group against another. In such conditions government can issue arbitrary and inconsistent decrees that dissimulate individuals by creating uncertainty about consequences of their actions. The certainty of law does not mean absence of any change; rather the absence of perpetual and unpredictable changes in laws. Such stability is important for a free society and economic coordination. For example, prominent economist and political philosopher Friedrich Hayek had argued that the certainty of law contributed to the prosperity of the West more that any other single factor. Other important principles of the rule of law are the generality and equality of the law, which require that all legal rules apply equally to everybody. These principles can be seen as safeguards against severe restrictions on liberty, because they require that all laws equally apply to those with political and coercive power as well as those who are governed. Principles of the generality and equality of the law exclude special privileges and arbitrary application of law, i.e. favoring one group at the expense of other citizens.[7] According to Friedrich Hayek, equality before the law is incompatible with any activity of the government aiming to achieve the material equality of different people. He asserts that a state's attempt to place people in the same (or similar) material position leads to an unequal treatment of individuals and to a compulsory redistribution of income.[8] Both of those actions are contributing to a decline in economic freedom.

Private property rights

A secure system of private property rights is an essential part of economic freedom. Such systems include two main rights: the right to control and benefit from property and the right to transfer property by voluntary means. These rights offer people the possibility of autonomy and self-determination according to theirs personal values and goals.[10] Economist Milton Friedman sees property rights as "the most basic of human rights and an essential foundation for other human rights."[11] With property rights protected, people are free to choose the use of their property, earn on it, and transfer it to anyone else, as long as they do it on a voluntary basis and do not resort to force, fraud or theft. In such conditions most people can achieve much greater personal freedom and development than under a regime of government coercion. A secure system of property rights also reduces uncertainty and encourages investments, creating favorable conditions for an economy to be successful.[12] Empirical evidence suggests that countries with strong property rights systems have economic growth rates almost twice as high as those of countries with weak property rights systems, and that a market system with significant private property rights is an essential condition for democracy.[13] According to Hernando de Soto, much of the poverty in the Third World countries is caused by the lack of Western systems of laws and well-defined and universally recognized property rights. De Soto argues that because of the legal barriers poor people in those countries can not utilize their assets to produce more wealth.[14]

Freedom of contract

Freedom of contract is the right to choose one's contracting parties and to trade with them on any terms and conditions one sees fit. Contracts permit individuals to create their own enforceable legal rules, adapted to their unique situations.[15] Parties decide whether contracts are profitable or fair, but once a contract is made they are obliged to fulfill its terms, even if they are going to sustain losses by doing so. Through making binding promises people are free to pursue their own interests. The main economic function of contracts is to provide transferability of property rights. Transferability largely depends on the enforceability of contracts, which is enabled by the judicial system. In Western societies the state does not enforce all types of contracts, and in some cases it intervenes by prohibiting certain arrangements, even if they are made between willing parties. However, not all contracts need to be enforced by the state. For example, in the United States there is a large number of third-party arbitration tribunals which resolve disputes under private commercial law.[16] Negatively understood, freedom of contract is freedom from government interference and from imposed value judgments of fairness. The notion of "freedom of contract" was given one of its most famous legal expressions in 1875 by Sir George Jessel MR:[17]

[I]f there is one thing more than another public policy requires it is that men of full age and competent understanding shall have the utmost liberty of contracting, and that their contracts when entered into freely and voluntarily shall be held sacred and shall be enforced by courts of justice. Therefore, you have this paramount public policy to consider – that you are not lightly to interfere with this freedom of contract.

Research on economic freedom

Living standards

Studies have shown economic freedom rankings correlate strongly with higher average income per person, higher income of the poorest 10%, higher life expectancy, higher literacy, lower infant mortality, higher access to water sources and less corruption.[18][19]

The people living in the top one-fifth of countries enjoy an average income of $23,450 and a growth rate in the 1990s of 2.56 percent per year; in contrast, the bottom one-fifth in the rankings had an average income of just $2,556 and a -0.85 percent growth rate in the 1990s. The poorest 10 percent of the population have an average income of just $728 in the lowest ranked countries compared with over $7,000 in the highest ranked countries.

The life expectancy of people living in the highest ranked nations is 20 years longer than for people in the lowest ranked countries.[20]

Happiness

Higher economic freedom, as measured by both the Heritage and the Fraser indices, correlates strongly with higher self-reported happiness.[21]

Peace

Economic freedom rankings can be compared to peace rankings. Economic Freedom of the World found that economic freedom is about 50 times more effective than democracy in diminishing violent conflict.[22]

Political freedom

Economic and political freedom both include the freedom from coercion from other individuals and from the government. Political and civil liberties have simultaneously expanded with market-based economies, and there is growing empirical evidence that economic and political freedoms are linked.[23] [24]

In Capitalism and Freedom (1962), Friedman developed the argument that economic freedom, while itself an extremely important component of total freedom, is also a necessary condition for political freedom. He commented that centralized control of economic activities was always accompanied with political repression.

In his view, voluntary character of all transactions in a free market economy and wide diversity that it permits are fundamental threats to repressive political leaders and greatly diminish power to coerce. Through elimination of centralized control of economic activities, economic power is separated from political power, and the one can serve as counterbalance to the other. Friedman feels that competitive capitalism is especially important to minority groups, since impersonal market forces protect people from discrimination in their economic activities for reasons unrelated to their productivity.[25]

In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek argued that "Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest; it is the control of the means for all our ends."[26]

Indices of Economic Freedom

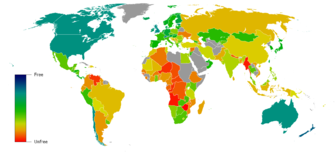

The annual surveys Economic Freedom of the World and Index of Economic Freedom are two indices which attempt to measure the degree of economic freedom in the world's nations, using a definition similar to laissez-faire capitalism.

The Economic Freedom of the World score for the entire world has grown considerably in recent decades. The average score has increased from 5.17 in 1985 to 6.4 in 2005. Of the nations in 1985, 95 nations increased their score, seven saw a decline, and six were unchanged.[27] Using the 2008 Index of Economic Freedom methodology world economic freedom has increased 2.6 points since 1995.[28]

Members of the World Bank Group also use Index of Economic Freedom as the indicator of investment climate, because it covers more aspects relevant to the private sector in wide number of countries.[29]

| Worldwide index of economic freedom 2008 - top and bottom 15 rankings published by The Wall Street Journal and the Heritage Foundation[30] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Capitalism

- Economic liberalism

- Laissez-faire

- List of countries by economic freedom

- Four Freedoms (European Union)

- Corruption Perceptions Index

Further reading

- Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty

- Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom

- Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom

- The Heritage Foundation, 2006 Index of Economic Freedom

- Ludwig von Mises, Economic Freedom and Interventionism

- Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom

References

- ^ Surjit S. Bhalla. Freedom and economic growth: a virtuous cycle?. Published in Democracy's Victory and Crisis. (1997). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521575834 p. 205

- ^ David A. Harper. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. (1999). Routledge. ISBN 0415153425 p.57, 64

- ^ Adam Jolly. OECD Economies and the World Today: Trends, Prospects and OECD Statistics. (2003). Kogan Page Business Books. ISBN 0749437812 p.87

- ^ Economic Freedom of the World Research Papers

- ^ Ralph V. Turner. Magna Carta. Pearson Education. (2003). ISBN 0582438268 p.1

- ^ Keith Charles Culver (edt). Readings in the Philosophy of Law. (1999). Broadview Press. ISBN 1551111799 p.14

- ^ David A. Harper. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development p.66-71

- ^ Daniel Rauhut, Neelambar Hatti, Carl-Axel Olsson. Economists and Poverty. Vedams eBooks (P) Ltd. ISBN 8179360164, p.204-205

- ^ Addision Wiggin, William Bonner. Financial Reckoning Day: Surviving the Soft Depression of the 21st Century. (2004). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471481300 p.137

- ^ David A. Harper. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. (1999). Routledge. ISBN 0415153425 p.74

- ^ Rose D. Friedman, Milton Friedman. Two Lucky People: Memoirs. (1998). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226264149 p.605

- ^ Bernard H. Siegan. Property and Freedom: The Constitution, the Courts, and Land-Use Regulation. Transaction Publishers. (1997). ISBN 1560009748 p.9, 230

- ^ David L. Weimer. The political economy of property rights. Published in The Political Economy of Property Rights. Cambridge University Press. (1997). ISBN 052158101X p.8-9

- ^ Hernando De Soto. The Mystery of Capital. Basic Books. (2003). ISBN 0465016154 p.210-211

- ^ John V. Orth. Contract and the Common Law. Published in The State and Freedom of Contract. (1998). Stanford University Press ISBN 0804733708 p.64

- ^ David A. Harper. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. (1999). Routledge. ISBN 0415153425 p.82-88

- ^ Hans van Ooseterhout, Jack J. Vromen, Pursey Heugensp. Social Institutions of Capitalism: Evolution and Design of Social Contracts. (2003). Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 1843764954 p.44

- ^ Economic Freedom of the World: 2004 Annual Report (pdf)

- ^ Index of Economic Freedom - Executive Summary (pdf)

- ^ Economic Freedom Needed To Alleviate Poverty

- ^ In Pursuit of Happiness Research. Is It Reliable? What Does It Imply for Policy? The Cato institute. April 11, 2007

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

fraserwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Freedom in the World. (1999). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0765806754 p.12

- ^ Lewis F. Abbott. British Democracy: Its Restoration & Extension, ISR/Google Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0-906321-31-7. Chapter Five: “The Legal Protection Of Democracy & Freedom: The Case For A New Written Constitution & Bill Of Rights”. [1]

- ^ Milton Friedman. Capitalism and freedom. (2002). The University of Chicago. ISBN 0226264211 p.8-21

- ^ Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, University Of Chicago Press; 50th Anniversary edition (1944), ISBN 0226320618 p.95

- ^ Economic Freedom of the World: 2005 Annual Report

- ^ Economic Freedom Holding Steady

- ^ Improving Investment Climates, World Bank Publications, 2006. ISBN 0821362828 p.221-224

- ^ Index of Economic Freedom - an annual guide published by The Wall Street Journal and The Heritage Foundation