Evolutionary psychology: Difference between revisions

Slrubenstein (talk | contribs) →Overview of theoretical foundations: removing controversial bit that violates our core content policy, NOR, per talk |

Undid revision 426439512 by Slrubenstein (talk) Standard, sourced info -- don' |

||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

In other words, altruism can evolve as long as the fitness ''cost'' of the altruistic act on the part of the actor is less than the ''degree of genetic relatedness'' of the recipient times the fitness ''benefit'' to that recipient. |

In other words, altruism can evolve as long as the fitness ''cost'' of the altruistic act on the part of the actor is less than the ''degree of genetic relatedness'' of the recipient times the fitness ''benefit'' to that recipient. |

||

This perspective reflects what is referred to as the [[gene-centered view of evolution]] and demonstrates that group selection is a very weak selective force. |

This perspective reflects what is referred to as the [[gene-centered view of evolution]] and demonstrates that group selection is a very weak selective force. |

||

===Overview of theoretical foundations=== |

|||

{| class="sortable wikitable" |

|||

|+ Central Concepts<ref>Mills, M.E. (2004). ''Evolution and motivation''. Symposium paper presented at the Western Psychological Association Conference, Phoenix, AZ. April, 2004.</ref> |

|||

<ref>Bernard, L. C., Mills, M. E., Swenson, L., & Walsh, R. P. (2005). [http://drmillslmu.com/publications/Bernard-Mills-Swenson-Walsh.pdf An evolutionary theory of human motivation]. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131, 129-184. See, in particular, Figure 2.</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Buss, D.M. 2011">Buss, D.M. (2011). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind</ref><ref>Gaulin, S. J. & McBurney, D. H. (2004). Evolutionary Psychology, (2nd Ed.). NJ: Prentice Hall.</ref><ref name="Dawkins, R. 1989">Dawkins, R. (1989). The Selfish Gene. (2nd Ed.) New York: Oxford University Press.</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! System level |

|||

! Problem |

|||

! Author |

|||

! Basic ideas |

|||

! Example adaptations |

|||

|- |

|||

| Individual |

|||

| How to survive? |

|||

| [[Charles Darwin]] (1859),<ref>Darwin, C. (1859). On The Origin of Species.</ref> (1872) <ref>Darwin, C. (1872), [[The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals]]</ref> |

|||

| '''''[[Natural Selection]] (or "survival selection")'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

The bodies and minds of organisms are made up of evolved adaptations designed to help the organism survive in a particular ecology (for example, the fur of polar bears, the eye, food preferences, etc.). |

|||

| Bones, skin, vision, pain perception, etc. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Dyad |

|||

| How to attract a mate and/or compete with members of one's own sex for access to the opposite sex? |

|||

| [[Charles Darwin]] (1871)<ref>Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex.</ref> |

|||

| '''''[[Sexual selection]]'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

Organisms can evolve physical and mental traits designed specifically to attract mates (e.g., the Peacock's tail) or to compete with members of one's own sex for access to the opposite sex (e.g., antlers). |

|||

| Peacock's tail, antlers, courtship behavior, etc. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Family & Kin |

|||

| Gene replication. How to help those with whom we share genes survive and reproduce? |

|||

| [[W.D. Hamilton]] (1964) |

|||

| '''''[[Inclusive fitness]] (or "gene's eye view", "kin selection") / Evolution of sexual reproduction'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

Selection occurs most robustly at the level of the gene, not the individual, group, or species. Reproductive success can thus be indirect, via shared genes in kin. Being altruistic toward kin can thus have genetic payoffs. (Also see [[Gene-centered view of evolution]]) |

|||

Also, Hamilton argued that sexual reproduction evolved primarily as a defense against pathogens (bacteria and viruses) to "shuffle genes" to create greater diversity, especially immunological variability, in offspring. |

|||

| Altruism toward kin, parental investment, the behavior of the social insects with sterile workers (e.g., ants). |

|||

|- |

|||

| Kin and Family |

|||

| How are resources best allocated in mating and/or parenting contexts to maximize inclusive fitness? |

|||

| [[Robert Trivers]] (1972) |

|||

| '''''[[Parental Investment]] Theory / Parent - Offspring Conflict / Reproductive Value'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

The two sexes often have conflicting strategies regarding how much to invest in offspring, and how many offspring to have. Parents allocate more resources to their offspring with higher reproductive value (e.g., "mom always liked you best"). Parents and offspring may have conflicting interests (e.g., when to wean, allocation of resources among offspring, etc.) |

|||

| Sexually dimorphic adaptations that result in a "battle of the sexes," parental favoritism, timing of reproduction, parent-offspring conflict, sibling rivalry, etc. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Non-kin small group |

|||

| How to succeed in competitive interactions with non-kin? How to select the best strategy given the strategies being used by competitors? |

|||

| [[John von Neumann|Neumann]] & [[Oskar Morgenstern|Morgenstern]] (1944);<br />[[John Maynard Smith|John Smith]] (1982) |

|||

| '''''Game Theory / [[Evolutionary Game Theory]]'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

Organisms adapt, or respond, to competitors depending on the strategies used by competitors. Strategies are evaluated by the probable payoffs of alternatives. In a population, this typically results in an "evolutionary stable strategy," or "evolutionary stable equilibrium" -- strategies that, on average, cannot be bettered by alternative strategies. |

|||

| Facultative, or frequency-dependent, adaptations. Examples: [[Chicken (game)#Hawk-Dove|hawks vs. doves]], cooperate vs. defect, fast vs. coy courtship, etc. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Non-kin small group |

|||

| How to maintain mutually beneficial relationships with non-kin in repeated interactions? |

|||

| [[Robert Trivers]] (1971) |

|||

| '''''"[[Tit for Tat]]" Reciprocity'''''<ref name="moralanimal"/> |

|||

A specific game strategy (see above) that has been shown to be optimal in achieving an evolutionary stable equilibrium in situations of repeated social interactions. One plays nice with non-kin if a mutually beneficially reciprocal relationship is maintained across multiple interactions, while cheating is punished. |

|||

| Cheater detection, emotions of revenge and guilt, etc. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Non-kin, large groups governed by rules and laws |

|||

| How to maintain mutually beneficial relationships with strangers with whom one may interact only once? |

|||

| [[Herbert Gintis]] (2000, 2003) and others |

|||

| '''''[[Reciprocity (social and political philosophy)#Patterns of Reciprocity|Generalized Reciprocity]]''''' |

|||

(Also called "strong reciprocity"). One can play nice with non-kin strangers even in single interactions if social rules against cheating are maintained by neutral third parties (e.g., other individuals, governments, institutions, etc.), a majority group members cooperate by generally adhering to social rules, and social interactions create a positive sum game (i.e., a bigger overall "pie" results from group cooperation). |

|||

Generalized reciprocity may be a set of adaptations that were designed for small in-group cohesion during times of high inter-tribal warfare with out-groups. |

|||

Today the capacity to be altruistic to in-group strangers may result from a serendipitous generalization (or "mismatch") between ancestral tribal living in small groups and today's large societies that entail many single interactions with anonymous strangers. (The dark side of generalized reciprocity may be that these adaptations may also underlie aggression toward out-groups.) |

|||

| '''''To in-group members:''''' |

|||

Capacity for generalized altruism, acting like a "good Samaritan," cognitive concepts of justice, ethics and human rights. |

|||

'''''To out-group members:''''' |

|||

Capacity for xenophobia, racism, warfare, genocide. |

|||

|- |

|||

| Large groups / culture. |

|||

| How to transfer information across distance and time? |

|||

| [[Richard Dawkins]] (1976),<ref name="Dawkins, R. 1989"/> |

|||

[[Susan Blackmore]] (2000),<ref name="Blackmore, Susan 2000">Blackmore, Susan. (2000) The Meme Machine</ref> |

|||

Boyd & Richerson (2004)<ref>Boyd & Richerson, (2004) ''Not by Genes Alone.''</ref> |

|||

| '''''Memetic Selection / [[Memetics]] / [[Dual inheritance theory]]''''' |

|||

Genes are not the only replicators subject to evolutionary change. Cultural characteristics, also referred to as "[[Memes]]"<ref name="Dawkins, R. 1989"/><ref name="Blackmore, Susan 2000"/> (e.g., ideas, rituals, tunes, cultural fads, etc.) can replicate and spread from brain to brain, and many of the same evolutionary principles that apply to genes apply to memes as well. Genes and memes may at times co-evolve ("gene-culture co-evolution"). |

|||

| Language, music, evoked culture, etc. Some possible by-products, or "exaptations," of language may include writing, reading, mathematics, etc. |

|||

|} |

|||

==Middle-level evolutionary theories== |

==Middle-level evolutionary theories== |

||

Revision as of 02:17, 29 April 2011

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Evolutionary psychology (EP) examines psychological traits — such as memory, perception, or language — from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify which human psychological traits are evolved adaptations, that is, the functional products of natural selection or sexual selection. Adaptationist thinking about physiological mechanisms, such as the heart, lungs, and immune system, is common in evolutionary biology. Evolutionary psychology applies the same thinking to psychology, arguing that the mind has a modular structure similar to that of the body with different modules having adapted to serve different functions. Evolutionary psychologists argue that much of human behavior is the output of psychological adaptations that evolved to solve recurrent problems in human ancestral environments.[1]

Psychological adaptations, according to EP, might include the abilities to infer others' emotions, to discern kin from non-kin, to identify and prefer healthier mates, to cooperate with others, and so on. Consistent with the theory of natural selection, evolutionary psychology sees organisms as often in conflict with others of their species, including mates and relatives. For example, mother mammals and their young offspring sometimes struggle over weaning, which benefits the mother more than the child. Evolutionary psychology emphasizes the importance of kin selection and reciprocity in allowing for prosocial traits such as altruism to evolve.[2] Like chimps and bonobos, humans have subtle and flexible social instincts, allowing them to form extended families, lifelong friendships, and political alliances.[2] In studies testing theoretical predictions, evolutionary psychologists have made modest findings on topics such as infanticide, intelligence, marriage patterns, promiscuity, perception of beauty, bride price and parental investment.[3]

Evolutionary psychologists hold that behaviors or traits that occur universally in all cultures are good candidates for evolutionary adaptations.[4] Evolved psychological adaptations (such as the ability to learn a language) interact with cultural inputs to produce specific behaviors (e.g., the specific language learned). Basic gender differences, such as greater eagerness for sex among men and greater coyness among women, are explained as adaptations that reflect the different reproductive strategies of males and females.[2][5] Evolutionary psychologists contrast their approach to what they term the "standard social science model," according to which the mind is a general-purpose cognition device shaped almost entirely by culture.[6][7]

Evolutionary psychology has its historical roots in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection.[4] Darwin's theory inspired William James’s functionalist approach to psychology.[4] Along with W.D. Hamilton's (1964) seminal papers on inclusive fitness, E. O. Wilson's Sociobiology (1975) helped to establish evolutionary thinking in psychology and the other social sciences.[4] While some critics argue that evolutionary psychology hypotheses are difficult or impossible to test,[4] evolutionary psychologists assert that is not impossible[8] and, indeed, that many empirical studies have either generally corroborated or disconfirmed evidence regarding hypotheses about specific psychological adaptations.[9][10] The influence of adaptationist approaches in psychology has been steadily increasing.[2][4]

Overview

Evolutionary psychology (EP) is an approach that views human nature as a universal set of evolved psychological adaptations to recurring problems in the ancestral environment. Proponents of EP suggest that it seeks to heal a fundamental division at the very heart of science --- that between the soft human social sciences and the hard natural sciences, and that the fact that human beings are living organisms demands that psychology be understood as a branch of biology. Anthropologist John Tooby and psychologist Leda Cosmides note:

"Evolutionary psychology is the long-forestalled scientific attempt to assemble out of the disjointed, fragmentary, and mutually contradictory human disciplines a single, logically integrated research framework for the psychological, social, and behavioral sciences—a framework that not only incorporates the evolutionary sciences on a full and equal basis, but that systematically works out all of the revisions in existing belief and research practice that such a synthesis requires."[11]

Just as human physiology and evolutionary physiology have worked to identify physical adaptations of the body that represent "human physiological nature," the purpose of evolutionary psychology is to identify evolved emotional and cognitive adaptations that represent "human psychological nature." EP is, to quote Steven Pinker, "not a single theory but a large set of hypotheses" and a term which "has also come to refer to a particular way of applying evolutionary theory to the mind, with an emphasis on adaptation, gene-level selection, and modularity." Evolutionary psychology adopts an understanding of the mind that is based on the computational theory of mind. It describes mental processes as computational operations, so that for example a fear response is described as arising from a neurological computation that inputs the perceptional data, e.g. a visual image of a spider and outputs the appropriate reaction, e.g. fear of possibly dangerous animals.

EP proposes that the human brain comprises many functional mechanisms,[12] called psychological adaptations or evolved cognitive mechanisms or cognitive modules, designed by the process of natural selection. Examples include language-acquisition modules, incest-avoidance mechanisms, cheater-detection mechanisms, intelligence and sex-specific mating preferences, foraging mechanisms, alliance-tracking mechanisms, agent-detection mechanisms, and others.

EP has roots in cognitive psychology and evolutionary biology. It also draws on behavioral ecology, artificial intelligence, genetics, ethology, anthropology, archaeology, biology, and zoology. EP is closely linked to sociobiology,[4] but there are key differences between them including the emphasis on domain-specific rather than domain-general mechanisms, the relevance of measures of current fitness, the importance of mismatch theory, and psychology rather than behaviour. Most of what is now labeled as sociobiological research is now confined to the field of behavioral ecology.[citation needed]

EP has been applied to the study of many fields, including economics, aggression, law, psychiatry, politics, literature, and sex.

Nikolaas Tinbergen's four categories of questions can help to clarify the distinctions between several different, but complementary, types of explanations.[13] Evolutionary psychology focuses primarily on the the "why?" questions, while traditional psychology focuses on the "how?" questions.[14]

| Sequential vs. Static Perspective | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical/Developmental Explanation of current form in terms of a historical sequence |

Current Form Explanation of the current form of species | ||

| How vs. Why Questions | Proximate How an individual organism's structures function |

Ontogeny Developmental explanations for changes in individuals, from DNA to their current form |

Mechanism Mechanistic explanations for how an organism's structures work |

| Evolutionary Why a species evolved the structures (adaptations) it has |

Phylogeny The history of the evolution of sequential changes in a species over many generations |

Adaptation A species trait that evolved to solve a reproductive or survival problem in the ancestral environment | |

Related disciplines

The content of EP has derived from, on the one hand, the biological sciences (especially evolutionary theory as it relates to ancient human environments, the study of paleoanthropology and animal behavior) and, on the other, the human sciences especially psychology. Evolutionary biology as an academic discipline emerged with the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s,[16] although it was not until the 1970s and 1980s that university departments included the term evolutionary biology in their titles. Several behavioural subjects relate to this core discipline: in the 1930s the study of animal behaviour (ethology) emerged with the work of Dutch biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen and Austrian biologists Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch.

In the 1970s, two major branches developed from ethology. Firstly, the study of animal social behavior (including humans) generated sociobiology, defined by its pre-eminent proponent Edward O. Wilson in 1975 as "the systematic study of the biological basis of all social behavior"[17] and in 1978 as "the extension of population biology and evolutionary theory to social organization".[18] Secondly, there was behavioral ecology which placed less emphasis on social behavior by focusing on the ecological and evolutionary basis of both animal and human behavior.

From psychology there are the primary streams of developmental, social and cognitive psychology. Establishing some measure of the relative influence of genetics and environment on behavior has been at the core of behavioral genetics and its variants, notably studies at the molecular level that examine the relationship between genes, neurotransmitters and behavior. Dual inheritance theory (DIT), developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, has a slightly different perspective by trying to explain how human behavior is a product of two different and interacting evolutionary processes: genetic evolution and cultural evolution. DIT is a "middle-ground" between much of social science, which views culture as the primary cause of human behavioral variation, and human sociobiology and evolutionary psychology which view culture as an insignificant by-product of genetic selection.[19]

Principles

Evolutionary psychology is founded on several core premises.

- The brain is an information processing device, and it produces behavior in response to external and internal inputs.[20][21]

- The brain's adaptive mechanisms were shaped by natural and sexual selection.[20][21]

- Different neural mechanisms are specialized for solving adaptive problems in humanity's evolutionary past.[20][21]

- The brain has evolved specialized neural mechanisms that were designed for solving problems that recurred over deep evolutionary time,[20] giving modern humans Stone age minds.[21]

- Most contents and processes of the brain are unconscious; and most mental problems that seem easy to solve are actually extremely difficult problems that are solved unconsciously by complicated neural mechanisms.[21]

- Human psychology consists of many specialized mechanisms, each sensitive to different classes of information or inputs. These mechanisms combine to produce manifest behavior.[20]

Evolutionary psychologists suggest that EP is not simply a subdiscipline of psychology but that evolutionary theory can provide a foundational, metatheoretical framework that integrates the entire field of psychology, in the same way it has for biology.[21]

History

19th century

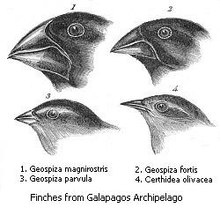

After his seminal work in developing theories of natural selection, Charles Darwin devoted much of his final years to the study of animal emotions and psychology. He wrote two books;The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871 and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872 that dealt with topics related to evolutionary psychology. He introduced the concepts of sexual selection to explain the presence of animal structures that seemed unrelated to survival, such as the peacock's tail. He also introduced theories concerning group selection and kin selection to explain altruism.[2] Darwin pondered why humans and animals were often generous to their group members. Darwin felt that acts of generosity decreased the fitness of generous individuals. This fact contradicted natural selection which favored the fittest individual. Darwin concluded that while generosity decreased the fitness of individuals, generosity would increase the fitness of a group. In this case, altruism arose due to competition between groups.[22] The following quote, from Darwin's Origin of Species, is often interpreted by evolutionary psychologists as indication of his foreshadowing the emergence of the field:

- In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.

- -- Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, 1859, p. 449.

Darwin's theory inspired William James's functionalist approach to psychology.[4] At the core of his theory was a system of "instincts."[23] James wrote that humans had many instincts, even more than other animals.[23] These instincts, he said, could be overridden by experience and by each other, as many of the instincts were actually in conflict with each other.[23]

According to Noam Chomsky, perhaps Anarchist thinker Peter Kropotkin could be credited as having founded evolutionary psychology, when in his 1902 book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution he argued that the human instinct for cooperation and mutual aid could be seen as stemming from evolutionary adaption.[24]

Post world war II

While Darwin's theories on natural selection gained acceptance in the early part of the 20th century, his theories on evolutionary psychology were largely ignored. Only after the second world war, in the 1950s, did interest increase in the systematic study of animal behavior. It was during this period that the modern field of ethology emerged. Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen were pioneers in developing the theoretical framework for ethology for which they would receive a Nobel prize in 1973.

Desmond Morris's book The Naked Ape attempted to frame human behavior in the context of evolution, but his explanations failed to convince academics because they were based on a teleological (goal-oriented) understanding of evolution. For example, he said that the pair bond evolved so that men who were out hunting could trust that their mates back home were not having sex with other men.[2]

Sociobiology

In 1975, E O Wilson built upon the works of Lorenz and Tinbergen by combining studies of animal behavior, social behavior and evolutionary theory in his book Sociobiology:The New Synthesis. Wilson included a chapter on human behavior. Wilson's application of evolutionary analysis to human behavior caused bitter divisions between biologists.[5][25]

With the publication of Sociobiology, evolutionary thinking for the first time had an identifiable presence in the field of psychology.[4] E O Wilson argues that the field of evolutionary psychology is essentially the same as sociobiology.[26] According to Wilson, the heated controversies surrounding Sociobiology:The New Synthesis, significantly stigmatized the term "sociobiology".

Origin of evolutionary psychology

The term evolutionary psychology was probably coined by American biologist Michael Ghiselin in a 1973 article published in the journal Science.[27] Jerome Barkow, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby popularized the term "evolutionary psychology" in their highly influential 1992 book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and The Generation of Culture.[28]

Evolutionary psychologists emphasized that organisms are "adaptation executors" rather than "fitness maximizers." In other words, organisms use behaviors that were adpative in the past rather than those that maximize fitness in the present. This distinction helps explain maladaptive behaviors, which are "fitness lags" resulting from novel environments. In addition, rather than focus primarily on overt behavior, EP attempts to identify underlying psychological adaptations (including emotional, motivational and cognitive mechanisms), and how these mechanisms interact with the developmental and current environmental influences to produce behavior.[29][30]

Before 1990, introductory psychology textbooks scarcely mentioned Darwin.[14] In the 1990s, evolutionary psychology was treated as a fringe theory,[9] and evolutionary psychologists depicted themselves as an embattled minority.[2] Coverage in psychology textbooks was largely hostile.[9] According to evolutionary psychologists, current coverage in psychology textbooks is usually neutral or balanced.[9]

The presence that evolutionary theory holds in psychology has been steadily increasing.[4] According to its proponents, evolutionary psychology now occupies a central place in psychological science.[9]

General evolutionary theory

EP is sometimes seen not simply as a subdiscipline of psychology but as a metatheoretical framework in which the entire field of psychology can be examined.[21]

Natural selection

Evolutionary psychologists consider Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection to be important to an understanding of psychology.[31] Natural selection occurs because individual organisms who are genetically better suited to the current environment leave more descendants, and their genes spread through the population, thus explaining why organisms fit their environments so closely.[31] This process is slow and cumulative, with new traits layered over older traits.[31] The advantages created by natural selection are known as adaptations.[31] Evolutionary psychologists say that animals, just as they evolve physical adaptations, evolve psychological adaptations.[31]

Evolutionary psychologists emphasize that natural selection mostly generates specialized adaptations, which are more efficient than general adaptations.[31] They point out that natural selection operates slowly, and that adaptations are sometimes out of date when the environment changes rapidly.[31] In the case of humans, evolutionary psychologists say that much of human nature was shaped during the stone age and may not match the contemporary environment.[31]

Sexual selection

Many traits that are selected for can actually hinder survival of the organism while increasing its reproductive opportunities. Consider the classic example of the peacock's tail. It is metabolically costly, cumbersome, and essentially a "predator magnet." What the peacock's tail does do is attract mates. Thus, the type of selective process that is involved here is what Darwin called "sexual selection". Sexual selection can be divided into two types:

- Intersexual selection, which refers to the traits that one sex generally prefers in the other sex, (e.g. the peacock's tail).

- Intrasexual competition, which refers to the competition among members of the same sex for mating access to the opposite sex, (e.g. two stags locking antlers).

Inclusive fitness

Inclusive fitness theory, proposed by William D. Hamilton, emphasized a "gene's-eye" view of evolution. Hamilton noted that what evolution ultimately selects are genes, not groups or species. From this perspective, individuals can increase the replication of their genes into the next generation not only directly via reproduction, by also indirectly helping close relatives with whom they share genes survive and reproduce. General evolutionary theory, in its modern form, is essentially inclusive fitness theory.

Inclusive fitness theory resolved the issue of how "altruism" evolved. The dominant, pre-Hamiltonian view was that altruism evolved via group selection: the notion that altruism evolved for the benefit of the group. The problem with this was that if one organism in a group incurred any fitness costs on itself for the benefit of others in the group, (i.e. acted "altruistically"), then that organism would reduce its own ability to survive and/or reproduce, therefore reducing its chances of passing on its altruistic traits.

Furthermore, the organism that benefited from that altruistic act and only acted on behalf of its own fitness would increase its own chance of survival and/or reproduction, thus increasing its chances of passing on its "selfish" traits. Inclusive fitness resolved "the problem of altruism" by demonstrating that altruism can evolve via kin selection as expressed in Hamilton's rule:

In other words, altruism can evolve as long as the fitness cost of the altruistic act on the part of the actor is less than the degree of genetic relatedness of the recipient times the fitness benefit to that recipient. This perspective reflects what is referred to as the gene-centered view of evolution and demonstrates that group selection is a very weak selective force.

Overview of theoretical foundations

| System level | Problem | Author | Basic ideas | Example adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | How to survive? | Charles Darwin (1859),[37] (1872) [38] | Natural Selection (or "survival selection")[2]

The bodies and minds of organisms are made up of evolved adaptations designed to help the organism survive in a particular ecology (for example, the fur of polar bears, the eye, food preferences, etc.). |

Bones, skin, vision, pain perception, etc. |

| Dyad | How to attract a mate and/or compete with members of one's own sex for access to the opposite sex? | Charles Darwin (1871)[39] | Sexual selection[2]

Organisms can evolve physical and mental traits designed specifically to attract mates (e.g., the Peacock's tail) or to compete with members of one's own sex for access to the opposite sex (e.g., antlers). |

Peacock's tail, antlers, courtship behavior, etc. |

| Family & Kin | Gene replication. How to help those with whom we share genes survive and reproduce? | W.D. Hamilton (1964) | Inclusive fitness (or "gene's eye view", "kin selection") / Evolution of sexual reproduction[2]

Selection occurs most robustly at the level of the gene, not the individual, group, or species. Reproductive success can thus be indirect, via shared genes in kin. Being altruistic toward kin can thus have genetic payoffs. (Also see Gene-centered view of evolution) Also, Hamilton argued that sexual reproduction evolved primarily as a defense against pathogens (bacteria and viruses) to "shuffle genes" to create greater diversity, especially immunological variability, in offspring. |

Altruism toward kin, parental investment, the behavior of the social insects with sterile workers (e.g., ants). |

| Kin and Family | How are resources best allocated in mating and/or parenting contexts to maximize inclusive fitness? | Robert Trivers (1972) | Parental Investment Theory / Parent - Offspring Conflict / Reproductive Value[2]

The two sexes often have conflicting strategies regarding how much to invest in offspring, and how many offspring to have. Parents allocate more resources to their offspring with higher reproductive value (e.g., "mom always liked you best"). Parents and offspring may have conflicting interests (e.g., when to wean, allocation of resources among offspring, etc.) |

Sexually dimorphic adaptations that result in a "battle of the sexes," parental favoritism, timing of reproduction, parent-offspring conflict, sibling rivalry, etc. |

| Non-kin small group | How to succeed in competitive interactions with non-kin? How to select the best strategy given the strategies being used by competitors? | Neumann & Morgenstern (1944); John Smith (1982) |

Game Theory / Evolutionary Game Theory[2]

Organisms adapt, or respond, to competitors depending on the strategies used by competitors. Strategies are evaluated by the probable payoffs of alternatives. In a population, this typically results in an "evolutionary stable strategy," or "evolutionary stable equilibrium" -- strategies that, on average, cannot be bettered by alternative strategies. |

Facultative, or frequency-dependent, adaptations. Examples: hawks vs. doves, cooperate vs. defect, fast vs. coy courtship, etc. |

| Non-kin small group | How to maintain mutually beneficial relationships with non-kin in repeated interactions? | Robert Trivers (1971) | "Tit for Tat" Reciprocity[2]

A specific game strategy (see above) that has been shown to be optimal in achieving an evolutionary stable equilibrium in situations of repeated social interactions. One plays nice with non-kin if a mutually beneficially reciprocal relationship is maintained across multiple interactions, while cheating is punished. |

Cheater detection, emotions of revenge and guilt, etc. |

| Non-kin, large groups governed by rules and laws | How to maintain mutually beneficial relationships with strangers with whom one may interact only once? | Herbert Gintis (2000, 2003) and others | Generalized Reciprocity

(Also called "strong reciprocity"). One can play nice with non-kin strangers even in single interactions if social rules against cheating are maintained by neutral third parties (e.g., other individuals, governments, institutions, etc.), a majority group members cooperate by generally adhering to social rules, and social interactions create a positive sum game (i.e., a bigger overall "pie" results from group cooperation). Generalized reciprocity may be a set of adaptations that were designed for small in-group cohesion during times of high inter-tribal warfare with out-groups. Today the capacity to be altruistic to in-group strangers may result from a serendipitous generalization (or "mismatch") between ancestral tribal living in small groups and today's large societies that entail many single interactions with anonymous strangers. (The dark side of generalized reciprocity may be that these adaptations may also underlie aggression toward out-groups.) |

To in-group members:

Capacity for generalized altruism, acting like a "good Samaritan," cognitive concepts of justice, ethics and human rights. To out-group members: Capacity for xenophobia, racism, warfare, genocide. |

| Large groups / culture. | How to transfer information across distance and time? | Richard Dawkins (1976),[36]

Susan Blackmore (2000),[40] Boyd & Richerson (2004)[41] |

Memetic Selection / Memetics / Dual inheritance theory

Genes are not the only replicators subject to evolutionary change. Cultural characteristics, also referred to as "Memes"[36][40] (e.g., ideas, rituals, tunes, cultural fads, etc.) can replicate and spread from brain to brain, and many of the same evolutionary principles that apply to genes apply to memes as well. Genes and memes may at times co-evolve ("gene-culture co-evolution"). |

Language, music, evoked culture, etc. Some possible by-products, or "exaptations," of language may include writing, reading, mathematics, etc. |

Middle-level evolutionary theories

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Middle-level evolutionary theories are consistent with general evolutionary theory, but focus on certain domains of functioning (Buss, 2011)[42] Specific evolutionary psychology hypotheses may be derivative from a mid-level theory (Buss, 2011). Three very important middle-level evolutionary theories were contributed by Robert Trivers as well as Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson[43][44][45]

- The theory of parent-offspring conflict rests on the fact that even though a parent and his/her offspring are 50% genetically related, they are also 50% genetically different. All things being equal, a parent would want to allocate their resources equally amongst their offspring, while each offspring may want a little more for themselves. Furthermore, an offspring may want a little more resources from the parent than the parent is willing to give. In essence, parent-offspring conflict refers to a conflict of adaptive interests between parent and offspring. However, if all things are not equal, a parent may engage in discriminative investment towards one sex or the other, depending on the parent's condition.

- The Trivers–Willard hypothesis, which proposes that parents will invest more in the sex that gives them the greatest reproductive payoff (grandchildren) with increasing or marginal investment. Females are the heavier parental investors in our species. Because of that, females have a better chance of reproducing at least once in comparison to males, but males in good condition have a better chance of producing high numbers of offspring than do females in good condition. Thus, according to the Trivers–Willard hypothesis, parents in good condition are predicted to favor investment in sons, and parents in poor condition are predicted to favor investment in daughters.

- r/K selection theory,[43] which, in ecology, relates to the selection of traits in organisms that allow success in particular environments. r-selected species, i.e., species in unstable or unpredictable environments, produce many offspring, each of which is unlikely to survive to adulthood. By contrast, K-selected species, i.e., species in stable or predictable environments, invest more heavily in fewer offspring, each of which has a better chance of surviving to adulthood.

- Life history theory posits that the schedule and duration of key events in an organism's lifetime are shaped by natural selection to produce the largest possible number of surviving offspring. For any given individual, available resources in any particular environment are finite. Time, effort, and energy used for one purpose diminishes the time, effort, and energy available for another. Examples of some major life history characteristics include: age at first reproductive event, reproductive lifespan and aging, and number and size of offspring. Variations in these characteristics reflect different allocations of an individual's resources (i.e., time, effort, and energy expenditure) to competing life functions. For example, attachment theory proposes that caregiver attentiveness in early childhood can determine later adult attachment style. Also, Jay Belsky and others have found evidence that if the father is absent from the home, girls reach first menstruation earlier and also have more short term sexual relationships as women.[46]

Evolved psychological mechanisms

At a proximal level, evolutionary psychology is based on the hypothesis that, just like hearts, lungs, livers, kidneys, and immune systems, cognition has functional structure that has a genetic basis, and therefore has evolved by natural selection. Like other organs and tissues, this functional structure should be universally shared amongst a species, and should solve important problems of survival and reproduction. Evolutionary psychologists seek to understand psychological mechanisms by understanding the survival and reproductive functions they might have served over the course of evolutionary history.

While philosophers have generally considered human mind to include broad faculties, such as reason and lust, evolutionary psychologists describe EPMs as narrowly evolved to deal with specific issues, such as catching cheaters or choosing mates.

Some mechanisms, termed domain-specific, deal with recurrent adaptive problems over the course of human evolutionary history. Domain-general mechanisms, on the other hand, deal with evolutionary novelty.

Products of evolution: adaptations, exaptations, byproducts, and random variation

Not all traits of organisms are adaptations. As noted in the table below, traits may also be exaptations, byproducts of adaptations (sometimes called "spandrels"), or random variation between individuals. For more on these distinctions, see Buss, et al., (1998).

Psychological adaptations are hypothesized to be innate or relatively easy to learn, and to manifest in cultures worldwide. For example, the ability of toddlers to learn a language with virtually no training is likely to be an psychological adaptation. On the other hand, ancestral humans did not read or write, thus today learning to read and write require extensive training, and presumably represent byproducts of cognitive processing that use psychological adaptations designed for other functions.[47]

| Adaptation | Exaptation | By-Product | Random Noise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Organismic trait designed to solve an ancestral problem(s). Shows complexity, special "design", functionality | Adaptation that has been "re-designed" to solve a different adaptive problem. | Byproduct of an adapative mechanism with no current or ancestral function | Random variations in an adaptation or byproduct |

| Physiological Example | Bones / Umbilical cord | Small bones of the inner ear | White color of bones / Belly button | Bumps on the skull, convex or concave belly button shape |

| Psychological Example | Toddlers’ ability to learn to talk with minimal instruction. | ? | Ability to learn to read and write. | Within-sex variations in voice pitch. |

One of the tasks of evolutionary psychology is to identify which psychological traits are likely to be adaptations, byproducts or random variation. George C Williams in his book Adaptation and Natural Selection, suggested that an "adaptation is a special and onerous concept that should only be used where it is really necessary",.[48] As noted by Williams and others, adaptations can be identified by their improbable complexity, species universality, and adaptive functionality.

Obligate vs. facultative adaptations

An important question to ask about an adaptation is whether it is generally obligate (relatively robust in the face of typical environmental variation) or facultative (sensitive to typical environmental variation)? [49] The sweet taste of sugar and the pain of hitting your knee against concrete are the result of fairly obligate psychological adaptations—typical environmental variability during development does not much affect their operation. On the other hand, facultative adaptations are somewhat like "if-then" statements. For example, adult attachment style seems particularly sensitive to early childhood experiences. As adults, the propensity to develop close, trusting bonds with others is dependent on whether early childhood caregivers could be trusted to provide reliable assistance and attention. The adaptation for skin to tan is conditional to exposure to sunlight—this is an example of another facultative adaptation. If a psychological adaptation is generally facultative, evolutionary psychologists are particularly interested in learning how specific types of developmental and current environmental inputs influence the expression of the psychological adaptation.

Cultural universals

Evolutionary psychologists hold that behaviors or traits that occur universally in all cultures are good candidates for evolutionary adaptations.[4] Cultural universals include behaviors related to language, cognition, social roles, gender roles, and technology.

Environment of evolutionary adaptedness

EP argues that to properly understand the functions of the brain, one must understand the properties of the environment in which the brain evolved. That environment is often referred to as the "environment of evolutionary adaptedness" (EEA).[50]

The term "environment of evolutionary adaptedness" was coined by John Bowlby as part of attachment theory. It refers to the environment to which a particular evolved mechanism is adapted. More specifically, the EEA is defined as the set of historically recurring selection pressures that formed a given adaptation, as well as those aspects of the environment that were necessary for the proper development and functioning of the adaptation.

Human EEA

Humans, comprising the genus Homo, appeared between 1.5 and 2.5 million years ago, a time that roughly coincides with the start of the Pleistocene 1.8 million years ago. Because the Pleistocene ended a mere 12,000 years ago, most human adaptations either newly evolved during the Pleistocene, or were maintained by stabilizing selection during the Pleistocene. Evolutionary psychology therefore proposes that the majority of human psychological mechanisms are adapted to reproductive problems frequently encountered in Pleistocene environments.[51] In broad terms, these problems include those of growth, development, differentiation, maintenance, mating, parenting, and social relationships.

The EEA is significantly different from modern society.[10] Our ancestors lived in smaller groups, had more cohesive cultures, and had more stable and rich contexts for identity and meaning.[10] Researchers look to existing hunter-gatherer societies for clues as to how our hunter-gatherer ancestors lived.[2] Since hunter-gatherer societies are egalitarian, the ancestral population may have been egalitarian as well, a social pattern different from the hierarchies found in chimp bands.[2] Unfortunately, the few surviving hunter-gatherer societies are different from each other, and they have been pushed out of the best land and into harsh environments, so it is not clear how closely they reflect ancestral culture.[2]

Evolutionary psychologists sometimes look to chimpanzees, bonobos, and other great apes for insight into human ancestral behavior.[2] Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jetha argue that evolutionary psychologists have overemphasized our similarity to chimps, which are more violent, while underestimating our similarity to bonobos, which are more peaceful.[52]

Mismatches

Since an organism's adaptations were suited to its ancestral environment, a new and different environment can create a mismatch. Because humans are mostly adapted to Pleistocene environments, psychological mechanisms sometimes exhibit "mismatches" to the modern environment. One example is the fact that although about 10,000 people are killed with guns in the US annually,[53] whereas spiders and snakes kill only a handful, people nonetheless learn to fear spiders and snakes about as easily as they do a pointed gun, and more easily than an unpointed gun, rabbits or flowers.[54] A potential explanation is that spiders and snakes were a threat to human ancestors throughout the Pleistocene, whereas guns (and rabbits and flowers) were not. There is thus a mismatch between our evolved fear-learning psychology and the modern environment.[55][56]

This mismatch also shows up in the phenomena of the supernormal stimulus-- a stimulus that elicits a response more strongly than the stimulus for which it evolved. The term was coined by Nobel Laureate Niko Tinbergen to describe animal behavior, but Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett has pointed out that supernormal stimulation governs the behavior of humans as powerfully as that of animals. She explains junk food as an exaggerated stimulus to cravings for salt, sugar, and fats,[57] and she describes how television is an exaggeration of social cues of laughter, smiling faces and attention-grabbing action.[58] Magazine centerfolds and double cheeseburgers pull instincts intended for an EEA where breast development was a sign of health, youth and fertility in a prospective mate, and fat was a rare and vital nutrient.[59]

Research methods

One of the major goals of adaptationist research is to identify which organismic traits are likely to be adaptations, and which are byproducts or random variations. As noted earlier, adaptations are expected to show evidence of complexity, functionality, and species universality, while byproducts or random variation will not. In addition, adaptations are expected to manifest as proximate mechanisms that interact with the environment in either a generally obligate or facultative fashion (see above). Evolutionary psychologists are also interested in identifying these proximate mechanisms (sometimes termed "mental mechansims" or "psychological adaptations") and what type of information they take as input, how they process that information, and their outputs.[49]

Evolutionary psychologists use several methods and data sources to test their hypotheses, as well as various comparative methods to test for similarities and differences between: humans and other species, males and females, individuals within a species, and between the same individuals in different contexts. They also use more traditional experimental methods involving, for example, dependent and independent variables. Recently, methods and tools have been introduced based on fictional scenarios,[60] mathematical models,[61] and multi-agent computer simulations.[62]

Evolutionary psychologists also use various sources of data for testing, including archeological records, data from hunter-gatherer societies, observational studies, self-reports, public records, and human products.[63]

Major areas of research

Foundational areas of research in evolutionary psychology can be divided into broad categories of adaptive problems that arise from the theory of evolution itself: survival, mating, parenting, family and kinship, interactions with non-kin, and cultural evolution.

Survival and individual level psychological adaptations

Problems of survival are thus clear targets for the evolution of physical and psychological adaptations. Major problems our ancestors faced included (a) food selection and acquisition, (b) territory selection and physical shelter, and (c) avoiding predators and other environmental threats. See Buss (2011)[34] for descriptions of various psychological adaptations that have evolved to deal with these challenges of survival.

Proponents of EP suggests that adaptationism can serve as a foundational meta theory for the entire discipline and thus it may offer a way to integrate different psychological phenomenon. They suggest that evolutionary theory can integrate the entire field of psychological science in much they same way that evolutionary theory has integrated the field of biology.[64]

Consciousness

Consciousness is likely an evolved adaptation since it meets George Williams' criteria of species universality, complexity,[65] and functionality, and it is a trait that apparently increases fitness.[66]

In his paper "Evolution of consciousness," John Eccles argues that special anatomical and physical adaptations of the mammalian cerebral cortex gave rise to consciousness.[67] In contrast, others have argued that the recursive circuitry underwriting consciousness is much more primitive, having evolved initially in pre-mammalian species because it improves the capacity for interaction with both social and natural environments by providing an energy-saving "neutral" gear in an otherwise energy-expensive motor output machine.[68] Once in place, this recursive circuitry may well have provided a basis for the subsequent development of many of the functions that consciousness facilitates in higher organisms, as outlined by Bernard J. Baars.[69] Richard Dawkins suggested that we evolved consciousness in order to make ourselves the subjects of thought.[70] Daniel Povinelli suggests that large, tree-climbing apes evolved consciousness to take into account one's own mass when moving safely among tree branches.[70] Consistent with this hypothesis, Gordon Gallup found that chimps and orangutans, but not little monkeys or terrestrial gorillas, demonstrated self-awareness in mirror tests.[70]

The concept of consciousness can refer to voluntary action, awareness, or wakefulness.[70] However, even voluntary behavior involves unconscious mechanisms.[70] Many cognitive processes take place in the cognitive unconscious, unavailable to conscious awareness.[70] Some behaviors are conscious when learned but then become unconscious, seemingly automatic.[70] Learning, especially implicitly learning a skill, can take place outside of consciousness.[70] For example, plenty of people know how to turn right when they ride a bike, but very few can accurately explain how they actually do so.[70] Evolutionary psychology approaches self-deception as an adaptation that can improve one's results in social exchanges.[70] Sleep may have evolved to conserve energy when activity would be less fruitful or more dangerous, such as at night, especially in winter.[70]

Sensation and perception

Many experts, such as Jerry Fodor, write that the purpose of perception is knowledge, but evolutionary psychologists hold that its primary purpose is to guide action.[71] For example, they say, depth perception seems to have evolved not to help us know the distances to other objects but rather to help us move around in space.[71] Evolutionary psychologists say that animals from fiddler crabs to humans use eyesight for collision avoidance, suggesting that vision is basically for directing action, not providing knowledge.[71]

Building and maintaining sense organs is metabolically expensive, so these organs evolve only when they improve an organism's fitness.[71] More than half the brain is devoted to processing sensory information, and the brain itself consumes roughly one-fourth of one's metabolic resources, so the senses must provide exceptional benefits to fitness.[71] Perception accurately mirrors the world; animals get useful, accurate information through their senses.[71]

Scientists who study perception and sensation have long understood the human senses as adaptations.[71] Depth perception consists of processing over half a dozen visual cues, each of which is based on a regularity of the physical world.[71] Vision evolved to respond to the narrow range of electromagnetic energy that is plentiful and that does not pass through objects.[71] Sound waves go around corners and interact with obstacles, creating a complex pattern that includes useful information about the sources of and distances to objects.[71] Larger animals naturally make lower-pitched sounds as a consequence of their size.[71] The range over which an animal hears, on the other hand, is determined by adaptation. Homing pigeons, for example, can hear very low-pitched sound (infrasound) that carries great distances, even though most smaller animals detect higher-pitched sounds.[71] Taste and smell respond to chemicals in the environment that are thought to have been significant for fitness in the EEA.[71] For example, salt and sugar were apparently both valuable to our ancestors, and we are favor salty and sweet tastes.[71] The sense of touch is actually many senses, including pressure, heat, cold, tickle, and pain.[71] Pain, while unpleasant, is adaptive.[71] An important adaptation for senses is range shifting, by which the organism becomes temporarily more or less sensitive to sensation.[71] For example, one's eyes automatically adjust to dim or bright ambient light.[71] Sensory abilities of different organisms often coevolve, as is the case with the hearing of echolocating bats and that of the moths that have evolved to respond to the sounds that the bats make.[71]

Evolutionary psychologists claim that perception demonstrates the principle of modularity, with specialized mechanisms handling particular perception tasks.[71] For example, people with damage to a particular part of the brain suffer from the specific defect of not being able to recognize faces (prospagnosia).[71] EP suggests that this indicates a so-called face-reading module.[71]

Emotion and motivation

Motivations direct and energize behavior, while emotions provide the affective component to motivation, positive or negative.[72] In the early 1970s, Paul Ekman and colleagues began a line of research that suggests that many emotions are universal.[72] He found evidence that humans share at least five basic emotions: fear, sadness, happiness, anger, and disgust.[72] Social emotions evidently evolved to motivate social behaviors that were adaptive in the EEA.[72] For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual's reputation as someone to be feared.[72] Shame and pride can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one's standing in a community, and self-esteem is one's estimate of one's status.[2][72]

Cognition

Cognition refers to internal representations of the world and internal information processing. From an EP perspective, cognition is not "general purpose," but uses heuristics, or strategies, that generally increase the likelihood of solving problems our ancestors routinely faced. For example, humans are far more likely to solve logic problems that involve detecting cheating (a common problem given our social nature) than the same logic problem put in purely abstract terms.[73] Since our ancestors did not encounter truly random events, we may be cognitively predisposed to incorrectly identify patterns in random sequences. "Gamblers' Fallacy" is one example of this. Gamblers may falsely believe that they have hit a "lucky streak" even when each outcome is actually random and independent of previous trials. Most people believe that if a fair coin has been flipped 9 times and Heads appears each time, that on the tenth flip, there is a greater than 50% chance of getting Tails.[72] Humans find it far easier to make diagnoses or predictions using frequency data than when the same information is presented as probabilities or percentages, presumably because our ancestors lived in relatively small tribes (unusually with less that 150 people) where frequency information was more readily available.[72]

Personality

Evolutionary psychology is primarily interested in finding commonalities between people, or basic human psychological nature. From an evolutionary perspective, the fact that people have fundamental differences in personality traits initially presents something of a puzzle.[74] (Note: The field of behavioral genetics is concerned with statistically partitioning differences between people into genetic and environmental sources of variance. However, understanding the concept of heritability can be tricky—heritability refers only to the differences between people, never the degree to which the traits of an individual are due to environmental or genetic factors, since traits are always a complex interweaving of both.)

Personality traits are conceptualized by evolutionary psychologists as due to normal variation around an optimum, or due to frequency-dependent selection, or facultative adaptations. Like variability in height, some personality traits may be simply reflect inter-individual variability around a general optimum.[74] Or, personality traits may represent different genetically predisposed "behavioral morphs" -- alternate behavioral strategies that depend on the frequency of competing behavioral strategies in the population. For example, if most of the population is generally trusting and gullible, the behavioral morph of being a "cheater" (or, in the extreme case, a sociopath) may be advantageous.[75] Finally, like many other psychological adaptations, personality traits may be facultative—sensitive to typical variations in the social environment, especially during early development. For example, later born children are more likely than first borns to be rebellious, less conscientious and more open to new experiences, which may be advantageous to them given their particular niche in family structure.[76]

Language

According to Steven Pinker, who builds on the work by Noam Chomsky, the universal human ability to learn to talk between the ages of 1 - 4, basically without training, suggests that language acquisition is a distinctly human psychological adaptation (see, in particular, Pinker's The Language Instinct). Pinker and Bloom (1990) argue that language as a mental faculty shares many likenesses with the complex organs of the body which suggests that, like these organs, language has evolved as an adaptation, since this is the only known mechanism by which such complex organs can develop.[77] Pinker follows Chomsky in arguing that the fact that children can learn any human language with no explicit instruction suggests that language, including most of grammar, is basically innate and that it only needs to be activated by interaction. Chomsky himself does not believe language to have evolved as an adaption, but suggests that it likely evolved as a byproduct of some other adaptation, a so-called spandrel. But Pinker and Bloom argue that the organic nature of language strongly suggests that it has an adaptational origin.[78]

Evolutionary Psychologists have taken the research linking the gene FOXP2 to linguistic behavior in animals and in humans, who share have a specific allelle, to be suggestive of a genetic basis for the language faculty.[79] While all language specialists agree that humans are innately able to acquire language, the theory of evolutionary psychology that sees language as a separate module of the human mind evolved through adaptation, is only one theory among many of the evolutionary origins of human language, and no single theory, modular or otherwise, is currently conclusively supported by evidence.[80]

Currently several competing theories about the evolutionary origin of language coexist, none of them having achieved a general consensus. Researchers of language acquisition in primates and humans such as Michael Tomasello and Talmy Givón, argue that the innatist framework has understated the role of imitation in learning and that it is not at all necessary to posit the existence of an innate grammar module to explain human language acquisition. Tomasello argues that studies of how children and primates actually acquire communicative skills suggests that we learn complex behavior through experience, so that instead of a module specifically dedicated to language acquisition, language is acquired by the same cognitive mechanisms that are used to acquire all other kinds of socially transmitted behavior.[81]

On the issue of whether language is best seen as having evolved as an adaptation or as a spandrel, evolutionary biologist W. Tecumseh Fitch, following Stephen J. Gould, argues that it is unwarranted to assume that every aspect of language is an adaptation, or that language as a whole is an adaptation. He criticizes some strands of evolutionary psychology for suggesting a pan-adaptionist view of evolution, and dismisses Pinker and Bloom's question of whether "Language has evolved as an adaptation" as being misleading. He argues instead that from a biological viewpoint the evolutionary origins of language is best conceptualized as being the probable result of a convergence of many separate adaptions into a complex system.[82] A similar argument is made by Terrence Deacon who in The Symbolic Species argues that the different features of language have co-evolved with the evolution of the mind and that the ability to use symbolic communication is integrated in all other cognitive processes.[83]

If the theory that language could have evolved as a single adaptation is accepted, the question becomes which of its many functions has been the basis of adaptation, several evolutionary hypotheses have been posited: that it evolved for the person of social grooming, that it evolved to as way to show mating potential or that it evolved to form social contracts. Evolutionary psychologists recognize that these theories are all speculative and that much more evidence is required to understand how language might have been selectively adapted.[84]

Mating

Given that sexual reproduction is the means by which genes are propagated into future generations, sexual selection plays a large role in the direction of human evolution. Human mating, then, is of interest to evolutionary psychologists who aim to investigate evolved mechanisms to attract and secure mates.[85] Several lines of research have stemmed from this interest, such as studies of mate selection[86][87][88] mate poaching,[89] and mate retention.[90]

Much of the research on human mating is based on parental investment theory,[91] which makes important predictions about the different strategies men and women will use in the mating domain (see above under "Middle-level evolutionary theories"). In essence, it predicts that women will be more selective when choosing mates, whereas men will not, especially under short-term mating conditions. This has led some researchers to predict sex differences in such domains as sexual jealousy,[92][93] (however, see also,)[94] wherein females will react more aversively to emotional infidelity and males will react more aversively to sexual infidelity. This particular pattern is predicted because the costs involved in mating for each sex are distinct. Women, on average, should prefer a mate who can offer some kind of resources (e.g., financial, commitment), which means that a woman would also be more at risk for losing those valued traits in a mate who commits an emotional infidelity. Men, on the other hand, are limited by the fact that they can never be certain of the paternity of their children because they do not bear the offspring themselves. This obstacle entails that sexual infidelity would be more aversive than emotional infidelity for a man because investing resources in another man's offspring does not lead to propagation of the man's own genes.

Another interesting line of research is that which examines women's mate preferences across the ovulatory cycle.[95][96] The theoretical underpinning of this research is that ancestral women would have evolved mechanisms to select mates with certain traits depending on their hormonal status. For example, the theory hypothesizes that, during the ovulatory phase of a woman's cycle (approximately days 10-15 of a woman's cycle),[97] a woman who mated with a male with high genetic quality would have been more likely, on average, to produce and rear a healthy offspring than a woman who mated with a male with low genetic quality. These putative preferences are predicted to be especially apparent for short-term mating domains because a potential male mate would only be offering genes to a potential offspring. This hypothesis allows researchers to examine whether women select mates who have characteristics that indicate high genetic quality during the high fertility phase of their ovulatory cycles. Indeed, studies have shown that women's preferences vary across the ovulatory cycle. In particular, Haselton and Miller (2006) showed that highly fertile women prefer creative but poor men as short-term mates. Creativity may be a proxy for good genes.[98] Research by Gangestad et al. (2004) indicates that highly fertile women prefer men who display social presence and intrasexual competition; these traits may act as cues that would help women predict which men may have, or would be able to acquire, resources.

Parenting

Reproduction is costly. Individuals are limited in the degree to which they can devote time and resources to producing and raising their young, and such expenditure may also be detrimental to their future condition, survival and further reproductive output. Parental investment is any parental expenditure (time, energy etc.) that benefits one offspring at a cost to parents' ability to invest in other components of fitness (Clutton-Brock 1991: 9; Trivers 1972). Components of fitness (Beatty 1992) include the well being of existing offspring, parents' future reproduction, and inclusive fitness through aid to kin (Hamilton, 1964). Parental investment theory is a branch of life history theory.

Robert Trivers' theory of parental investment predicts that the sex making the largest investment in lactation, nurturing and protecting offspring will be more discriminating in mating and that the sex that invests less in offspring will compete for access to the higher investing sex (see Bateman's principle[99]). Sex differences in parental effort are important in determining the strength of sexual selection.

The benefits of parental investment to the offspring are large and are associated with the effects on condition, growth, survival and ultimately, on reproductive success of the offspring. However, these benefits can come at the cost of parent's ability to reproduce in the future e.g. through the increased risk of injury when defending offspring against predators, the loss of mating opportunities whilst rearing offspring and an increase in the time to the next reproduction. Overall, parents are selected to maximise the difference between the benefits and the costs, and parental care will be likely to evolve when the benefits exceed the costs.

The Cinderella effect is a term used to describe the high incidence of stepchildren being physically, emotionally or sexually abused, neglected or murdered, or otherwise mistreated at the hands of their stepparents at significantly higher rates than their genetic counterparts. It takes its name from the fairy tale character Cinderella, who in the story was cruelly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters.[100] Daly and Wilson (1996) noted: "Evolutionary thinking led to the discovery of the most important risk factor for child homicide -- the presence of a stepparents. Parental efforts and investments are valuable resources, and selection favors those parental psyches that allocate effort effectively to promote fitness. The adaptive problems that challenge parental decision making include both the accurate identification of one's offspring and the allocation of one's resources among them with sensitivity to their needs and abilities to convert parental investment into fitness increments…. Stepchildren were seldom or never so valuable to one's expected fitness as one's own offspring would be, and those parental psyches that were easily parasitized by just any appealing youngster must always have incurred a selective disadvantage"(Daly & Wilson, 1996, p64 - 65). However, they note that that not all stepparents will "want" to abuse their partner's children, or that genetic parenthood is absolute insurance against abuse. They see step parental care is as primarily "mating effort" towards the genetic parent.[101]

Family and kin

Inclusive fitness is the sum of an organism's classical fitness (how many of its own offspring it produces and supports) and the number of equivalents of its own offspring it can add to the population by supporting others.[102] The first component is called classical fitness by Hamilton (1964).

From the gene's point of view, evolutionary success ultimately depends on leaving behind the maximum number of copies of itself in the population. Until 1964, it was generally believed that genes only achieved this by causing the individual to leave the maximum number of viable offspring. However, in 1964 W. D. Hamilton proved mathematically that, because close relatives of an organism share some identical genes, a gene can also increase its evolutionary success by promoting the reproduction and survival of these related or otherwise similar individuals. Hamilton claimed that this leads natural selection to favor organisms that would behave in ways that maximize their inclusive fitness. It is also true that natural selection favors behavior that maximizes personal fitness.

Hamilton's rule describes mathematically whether or not a gene for altruistic behaviour will spread in a population:

where

- is the reproductive cost to the altruist,

- is the reproductive benefit to the recipient of the altruistic behavior, and

- is the probability, above the population average, of the individuals sharing an altruistic gene – commonly viewed as "degree of relatedness".

The concept serves to explain how natural selection can perpetuate altruism. If there is an '"altruism gene"' (or complex of genes) that influences an organism's behavior to be helpful and protective of relatives and their offspring, this behavior also increases the proportion of the altruism gene in the population, because relatives are likely to share genes with the altruist due to common descent. Altruists may also have some way to recognize altruistic behavior in unrelated individuals and be inclined to support them. As Dawkins points out in The Selfish Gene (Chapter 6) and The Extended Phenotype,[103] this must be distinguished from the green-beard effect.

Psychological adaptations related to interactions with kin are facultative. Although it is generally true that humans tend to be more altruistic toward their kin than toward non-kin, there may be exceptions. Specific types of behavioral output are dependent on the interaction of both genetic and environmental influences. For example, John Bowlby and others have noted that patterns of attachment to others are dependent on early developmental experiences with caregivers.[104] In any specific instance, the manifestation of emotional bonds into altruistic behaviour depends on early bonding experiences, and symbolic, economic and other cultural factors, which may or may not always coincide with consanguinity.[105]

Interactions with non-kin / reciprocity

Although interactions with non-kin are generally less altruistic compared to those with kin, cooperation can be maintained with non-kin via mutually beneficial reciprocity as was proposed by Robert Trivers.[106] If there are repeated encounters between the same two players in an evolutionary game in which each of them can choose either to "cooperate" or "defect," then a strategy of mutual cooperation may be favored even if it pays each player, in the short term, to defect when the other cooperates. Direct reciprocity can lead to the evolution of cooperation only if the probability, w, of another encounter between the same two individuals exceeds the cost-to-benefit ratio of the altruistic act:

- w > c/b

Reciprocity can also be indirect if information about previous interactions is shared. Reputation allows evolution of cooperation by indirect reciprocity. Natural selection favors strategies that base the decision to help on the reputation of the recipient: studies show that people who are more helpful are more likely to receive help. The calculations of indirect reciprocity are complicated and only a tiny fraction of this universe has been uncovered, but again a simple rule has emerged.[107] Indirect reciprocity can only promote cooperation if the probability, q, of knowing someone’s reputation exceeds the cost-to-benefit ratio of the altruistic act:

- q > c/b

One important problem with this explanation is that individuals may be able to evolve the capacity to obscure their reputation, reducing the probability, q, that it will be known.[108]

Trivers argues that friendship and various social emotions evolved in order to manage reciprocity.[109] Liking and disliking, he says, evolved to help our ancestors form coalitions with others who reciprocated and to exclude those who did not reciprocate.[109] Moral indignation may have evolved to prevent one's altruism from being exploited by cheaters, and gratitude may have motivated our ancestors to reciprocate appropriately after benefiting from others' altruism.[109] Likewise, we feel guilty when we fail to reciprocate.[110] These social motivations match what evolutionary psychologists expect to see in adaptations that evolved to maximize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks of reciprocity.[109]

Evolutionary psychologists say that humans have psychological adaptations that evolved specifically to help us identify nonreciprocators, commonly referred to as "cheaters."[109] In 1993, Robert Frank and his associates found that participants in a prisoner's dilemma scenario were often able to predict whether their partners would "cheat," based on a half hour of unstructured social interaction.[109] In a 1996 experiment, for example, Linda Mealey and her colleagues found that people were better at remembering the faces of people when those faces were associated with stories about those individuals cheating (such as embezzling money from a church).[109]

Evolution and culture

Evolutionary psychology incorporates insights derived from other disciplines about how cultural phenomena evolve over time. Theories that have applied evolutionary perspectives to cultural phenomena include memetics, cultural ecology, and dual inheritance theory (gene-culture co-evolution).[111]