Fanny Hill: Difference between revisions

I Feel Tired (talk | contribs) m →References in popular culture: In popular culture sections are discouraged under Wikipedia guidelines |

|||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

* ''Fanny Hill'' (USA, 1995), directed by [[Valentine Palmer]].<ref>{{imdb title|title=Fanny Hill (1995)|id=0138433}}</ref> |

* ''Fanny Hill'' (USA, 1995), directed by [[Valentine Palmer]].<ref>{{imdb title|title=Fanny Hill (1995)|id=0138433}}</ref> |

||

* ''[[Fanny Hill (2007 serial)|Fanny Hill]]'' (2007), written by [[Andrew Davies (writer)|Andrew Davies]] for the [[BBC]] and starring [[Rebecca Night]].<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,,1770058,00.html Article from ''The Guardian'']</ref> |

* ''[[Fanny Hill (2007 serial)|Fanny Hill]]'' (2007), written by [[Andrew Davies (writer)|Andrew Davies]] for the [[BBC]] and starring [[Rebecca Night]].<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,,1770058,00.html Article from ''The Guardian'']</ref> |

||

== References in popular culture == |

|||

* In a portrait that appears in the [[The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Volume I|first volume]] of [[Alan Moore]]'s ''[[The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen]]'', Fanny Hill is depicted as a member of the 18th Century version of the League. She also appears more prominently in [[The Black Dossier]] as a member of Gulliver's League, as well as a "sequel" to the original Hill novel, complete with illustrations by Kevin O Neill. The setting of her involvement with the League begins with her divorce from Charles after he is caught in the act in a brothel kept by former League member [[Forever Amber (novel)|Amber St. Clare]], and is shown to have been sexually involved with both [[Gulliver]] and [[Captain Clegg]] nearly 40 years before the second League was founded. She doesn't age as an effect of her stay at [[Horselberg]]. This version has apparently pursued a lesbian relationship with a character named [[Venus]] (who seems to be an amalgamation of the various versions of the Goddess of love in literature) for at least a century and a half as of the Black Dossier and in contrast to the novel's relationships this one seems to be enduring. |

|||

* The novel is also mentioned in [[Tom Lehrer]]'s song "Smut". |

|||

* A tongue-in-cheek reference to ''Fanny Hill'' appears in the 1968 David Niven, Lola Albright film ''[[The Impossible Years]]''. In one scene the younger daughter of Niven's character is seen reading ''Fanny Hill'', whereas his older daughter, Linda, has apparently graduated from Cleland's sensationalism and is seen reading [[Jean-Paul Sartre|Sartre]] instead. |

|||

* In the 1968 version of ''[[Yours, Mine and Ours (1968 film)|Yours, Mine, and Ours]]'', [[Henry Fonda]]'s character, Frank Beardsley, refers to "Fanny Hill" when giving some fatherly advice to his stepdaughter. Her boyfriend is pressuring her for sex and Frank says boys tried the same thing when he was her age. When she tries to tell him that things are different now he observes, "I don't know, they wrote 'Fanny Hill' in 1742 [sic] and they haven't found anything new since." |

|||

* The 2006-07 [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] musical, ''[[Grey Gardens (musical)|Grey Gardens]]'' has a comedic reference to ''Fanny Hill'' in the first act. Young Edith Bouvier Beale (aka 'little Edie') has just been confronted about a rumor of promiscuity that her mother, Mrs. Edith Bouvier Beale (aka 'Big Edie') told her fiance. 'Little Edie' was allegedly engaged to [[Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr.]] in 1941 until he discovered that 'Little Edie' may have been sexually acquainted with other men before him. 'Little Edie' implores Joe Kennedy not to break off the engagement and to wait for her father to come home and rectify the situation, vouching for her reputation. The musical line that 'Little Edie' sings in reference to ''Fanny Hill'' is: "While the other girls were reading ''Fanny Hill''/ I was reading [[Alexis de Tocqueville|De - Toc - que - ville]]" |

|||

*In an episode of ''[[M*A*S*H]]'', [[Radar O'Reilly]] thanks Sparky for sending the book ''Fanny Hill'' but says the last chapter was missing and asks "Whodunnit?" Sparky answers "Everybody." |

|||

*In the book ''Frost At Christmas'' by R.D. Wingfield, the vicar has a copy of Fanny Hill hidden in his trunk amongst other dirty books. |

|||

*In [[Harry Harrison]]'s novel ''[[Bill, the Galactic Hero]]'', the titular character is stationed on a [[starship]] named ''Fanny Hill''. |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 21:10, 1 September 2009

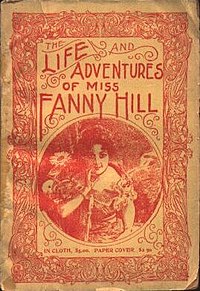

Cover of an undated American edition, c. 1910 | |

| Author | John Cleland |

|---|---|

| Original title | Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Erotic novel |

Publication date | November 21, 1748 & 1749 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-14-043249-3 |

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, popularly known as Fanny Hill, is a novel by John Cleland.

Written in Template:Lty while the author was in debtor's prison in London, it is considered the first modern "erotic novel" in English, and has become a byword for the battle of censorship of erotica.

Plot

The book concerns the eponymous character, who first appears in the novel as a poor country girl who is forced by poverty to leave her village home and go to a nearby town. There, she is tricked into working in a brothel, but before losing her virginity she escapes with a man named Charles with whom she has fallen in love. After several months of living together, Charles is sent out of the country unexpectedly by his father, and Fanny is forced to take up a succession of new lovers to survive.

Publishing history

The novel was published in two installments, on November 21, 1748 and February of 1749, respectively. Initially, there was no governmental reaction to the novel, and it was only in November 1749, a year after the first installment was published, that Cleland and his publisher were arrested and charged with "corrupting the King's subjects." In court, Cleland renounced the novel and it was officially withdrawn. However, as the book became popular, pirate editions appeared. In particular, an episode was interpolated into the book depicting homosexuality between men, which Fanny observes through a chink in the wall. Cleland published an expurgated version of the book in March 1750, but was nevertheless prosecuted for that, too, although the charges were subsequently dropped. Some historians, such as J. H. Plumb, have hypothesised that the prosecution was actually caused by the pirate edition containing the "sodomy" scene.

In the 19th century, copies of the book were sold "underground", and it was not until 1963, after the failure of the British obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley's Lover in 1960 that Mayflower Books, with Gareth Powell as Managing Director, published an unexpurgated paperback version of Fanny Hill.

The police became aware of the book a few days before publication after spotting a sign in the window of the Magic Shop in Tottenham Court Road in London, run by Ralph Gold. An officer went to the shop and bought a copy and delivered it to the Bow Street magistrate Sir Robert Blundell who issued a search warrant. At the same time two officers from the vice squad visited Mayflower Books in Vauxhall Bridge Road to determine if quantities of the book were kept on the premises. They interviewed the publisher, Gareth Powell, and took away the only five copies there. The police returned to the Magic Shop and seized 171 copies of the book, and in December Ralph Gold was summonsed under section 3 of the Obscenity Act. By then, Mayflower had distributed 82,000 copies of the book, but it was Gold rather than Mayflower or Fanny Hill that was being tried, although Mayflower covered the legal costs. The trial took place in February 1964. The defence argued that Fanny Hill was a historical source book and that it was a joyful celebration of normal non-perverted sex - bawdy rather than pornographic. The prosecution countered by stressing one atypical scene involving flagellation, and won. Mayflower decided not to appeal. But the case had highlighted the growing disconnect between the obscenity laws and the social realities of late 1960s Britain, and was instrumental in shifting views to the point where in 1970 an unexpurgated version of Fanny Hill was once again published in Britain.

The book eventually made its way to the United States where, in 1821, it was banned for obscenity. In 1963, G. B. Putnam published the book under the title John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure which also was immediately banned for obscenity. The publisher challenged the ban in court.

In a landmark decision in 1966, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Memoirs v. Massachusetts that the banned novel did not meet the Roth standard for obscenity.

In 1973, the Miller Test came into effect, and as a result the ban on the novel was lifted because although it appeals to the prurient interest and at points is patently offensive, the work taken as a whole does not lack literary or artistic value.

Erica Jong's 1980 novel Fanny purports to tell the story from Fanny's point of view, with Cleland as a character she complains fictionalized her life.

Extract

"...and now, disengag’d from the shirt, I saw, with wonder and surprise, what? not the play-thing of a boy, not the weapon of a man, but a maypole of so enormous a standard, that had proportions been observ’d, it must have belong’d to a young giant. Its prodigious size made me shrink again; yet I could not, without pleasure, behold, and even ventur’d to feel, such a length, such a breadth of animated ivory! perfectly well turn’d and fashion’d, the proud stiffness of which distended its skin, whose smooth polish and velvet softness might vie with that of the most delicate of our sex, and whose exquisite whiteness was not a little set off by a sprout of black curling hair round the root, through the jetty sprigs of which the fair skin shew’d as in a fine evening you may have remark’d the clear light ether through the branchwork of distant trees over-topping the summit of a hill: then the broad and blueish-cast incarnate of the head, and blue serpentines of its veins, altogether compos’d the most striking assemblage of figure and colours in nature. In short, it stood an object of terror and delight.

"But what was yet more surprising, the owner of this natural curiosity, through the want of occasions in the strictness of his home-breeding, and the little time he had been in town not having afforded him one, was hitherto an absolute stranger, in practice at least, to the use of all that manhood he was so nobly stock’d with; and it now fell to my lot to stand his first trial of it, if I could resolve to run the risks of its disproportion to that tender part of me, which such an oversiz’d machine was very fit to lay in ruins."

Film adaptations

Because of the book's notoriety (and public domain status), numerous film adaptations have been produced. Some of them are:

- Fanny Hill (USA/West Germany, 1964), starring Letícia Román, Miriam Hopkins, Ulli Lommel, Chris Howland; directed by Russ Meyer, Albert Zugsmith (uncredited) [1]

- Fanny Hill (Sweden, 1968), starring Diana Kjær, Hans Ernback, Keve Hjelm, Oscar Ljung; directed by Mac Ahlberg[2]

- Fanny Hill (West Germany/UK, 1983), starring Lisa Foster, Oliver Reed, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Shelley Winters; directed by Gerry O'Hara[3]

- Paprika (Italy, 1991), starring Deborah Caprioglio, Stéphane Bonnet, Stéphane Ferrara, Luigi Laezza, Rossana Gavinel, Martine Brochard and John Steiner; directed by Tinto Brass.[4]

- Fanny Hill (USA, 1995), directed by Valentine Palmer.[5]

- Fanny Hill (2007), written by Andrew Davies for the BBC and starring Rebecca Night.[6]

References

External links

- Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure at Project Gutenberg

- Charles Dickens's Themes A surprising allusion to Fanny Hill in Dombey and Son.

- BBC TV Adaptation First Broadcast October 2007