Fentanyl: Difference between revisions

Changed incorrect information entered by vandalist TAz69x...user is modifying information with rubbish. User will be reported. |

→undo Updated-Info-Deletion: - Updated information is pretty concrete, and direclty cited from the Ref. provided; if it is in fact incorrect, please start a Discussion post and explain why it is. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

| dependency_liability = Moderate - High}} |

| dependency_liability = Moderate - High}} |

||

'''Fentanyl''' — brand names include [[Actiq]], [[Duragesic]], [[Fentora]], and [[Sublimaze]]<ref>http://www.drugs.com/pro/sublimaze.html</ref> — is a synthetic primary [[mu opioid receptor|μ-opioid]] agonist commonly used to treat [[chronic pain|chronic breakthrough pain]] |

'''Fentanyl''' — brand names include [[Actiq]], [[Duragesic]], [[Fentora]], and [[Sublimaze]]<ref>http://www.drugs.com/pro/sublimaze.html</ref> — is a synthetic primary [[mu opioid receptor|μ-opioid]] agonist commonly used to treat [[chronic pain|chronic breakthrough pain]]. It is approximately 80 times more potent than [[morphine]],<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19252390</ref> with therapeutic efficacy of 0.83mg fentanyl equivalent to 75mg morphine per day, or 75 mg of [[pethidine]] in analgesic activity.<ref>http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/f/FentanylcitrateinjUSP.htm</ref> It has an [[LD50|LD<sub>50</sub>]] of 3.1 milligrams per kilogram in rats, 0.03 milligrams per kilogram in monkeys, and an undetermined [[LD50|LD<sub>50</sub>]] in humans. |

||

<ref>http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/f/FentanylcitrateinjUSP.htm</ref> It has an [[LD50|LD<sub>50</sub>]] of 3.1 milligrams per kilogram in rats, 0.03 milligrams per kilogram in monkeys, and an undetermined [[LD50|LD<sub>50</sub>]] in humans. |

|||

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Dr. [[Paul Janssen]] in 1959 following the medical inception of [[meperidine]] several years earlier, and based initially on the chemical starting point of [[piperidine]] and applicable opioid activity.<ref>http://www.pauljanssenaward.com/janssen/A_Personal_Perspective.pdf#zoom=100</ref> The widespread use of fentanyl triggered the production of fentanyl citrate, which entered the clinical practice as a general anaesthetic under the trade name [[Sublimaze]] in the 1960s. Following this, many other fentanyl analogs were developed and introduced into the medical practice, including [[Sufentanil]], [[Alfentanil]], [[Remifentanil]], and [[Lofentanil]]. |

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Dr. [[Paul Janssen]] in 1959 following the medical inception of [[meperidine]] several years earlier, and based initially on the chemical starting point of [[piperidine]] and applicable opioid activity.<ref>http://www.pauljanssenaward.com/janssen/A_Personal_Perspective.pdf#zoom=100</ref> The widespread use of fentanyl triggered the production of fentanyl citrate, which entered the clinical practice as a general anaesthetic under the trade name [[Sublimaze]] in the 1960s. Following this, many other fentanyl analogs were developed and introduced into the medical practice, including [[Sufentanil]], [[Alfentanil]], [[Remifentanil]], and [[Lofentanil]]. |

||

Revision as of 07:19, 19 August 2009

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Dependence liability | Moderate - High |

| Routes of administration | TD, IM, IV, oral, sublingual, buccal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 92% (transdermal) 50% (buccal) 33% (ingestion) |

| Protein binding | 80-85% |

| Metabolism | hepatic, primarily by CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | 7 hours (range 3–12 h) |

| Excretion | 60% Urinary (metabolites, <10% unchanged drug)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.468 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

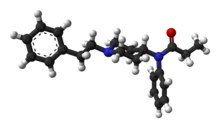

| Formula | C22H28N2O |

| Molar mass | 336.471 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 87.5 °C (189.5 °F) |

| |

Fentanyl — brand names include Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, and Sublimaze[3] — is a synthetic primary μ-opioid agonist commonly used to treat chronic breakthrough pain. It is approximately 80 times more potent than morphine,[4] with therapeutic efficacy of 0.83mg fentanyl equivalent to 75mg morphine per day, or 75 mg of pethidine in analgesic activity.[5] It has an LD50 of 3.1 milligrams per kilogram in rats, 0.03 milligrams per kilogram in monkeys, and an undetermined LD50 in humans.

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Dr. Paul Janssen in 1959 following the medical inception of meperidine several years earlier, and based initially on the chemical starting point of piperidine and applicable opioid activity.[6] The widespread use of fentanyl triggered the production of fentanyl citrate, which entered the clinical practice as a general anaesthetic under the trade name Sublimaze in the 1960s. Following this, many other fentanyl analogs were developed and introduced into the medical practice, including Sufentanil, Alfentanil, Remifentanil, and Lofentanil.

In the mid 1990s, fentanyl saw its first widespread palliative use with the clinical introduction of the Duragesic patch, followed in the next decade by the introduction of the first quick-acting prescription formations of fentanyl for personal use, the Actiq lollipop and Fentora buccal tablets. Through the delivery method of transdermal patches, fentanyl is currently the most widely used synthetic opioid in clinical practice, with several new delivery methods currently in development.[7] Fentanyl is classified as a Schedule II drug in the United States due to its potential for abuse.

History

Fentanyl was first synthesized by Paul Janssen under the label of his relatively newly formed Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1959. In the 1960s, fentanyl was introduced as an intravenous anesthetic under the trade name of Sublimaze. In the mid-1990s, Janssen Pharmaceutica developed and introduced into clinical trials the Duragesic patch, which is a formation of an inert alcohol gel infused with select fentanyl doses which are worn to provide constant administration of the opioid over a period of 48 to 72 hours. After a set of successful clinical trials, Duragesic fentanyl patches were introduced into the medical practice.

Following the patch, a flavored lollipop of fentanyl citrate mixed with inert fillers was introduced under the brand name of Actiq, becoming the first quick-acting formation of fentanyl for use with chronic breakthrough pain. More recently, fentanyl has been developed into an effervescent tab for buccal absorption much like the Actiq lollipop, followed by a buccal spray device for fast-acting relief and other delivery methods currently in development.

Chemistry

Synthesis

The synthesis of fentanyl (N-phenyl-N-(1-phenethyl-4-piperidinyl)propanamide) by Janssen Pharmaceutica was achieved in four steps, starting from 4-piperidinone hydrochloride. The 4-piperidinone hydrochloride was first reacted with phenethyl bromide to give N-phenethyl-4-piperidinone (NPP). Treatment of the NPP intermediate with aniline followed by reduction with sodium borohydride affording 4-anilino-N-phenethyl-piperidine (ANPP). Finally ANPP and propionic anhydride are reacted to form the amide product.

Analogues

The pharmaceutical industry has developed several analogues of fentanyl:

- Alfentanil (trade name Alfenta), an ultra-short acting (5–10 minutes) analgesic.

- Sufentanil (trade name Sufenta), a potent analgesic (5 to 10 times more potent than fentanyl) for use in heart surgery.

- Remifentanil (trade name Ultiva), currently the shortest acting opioid, has the benefit of rapid offset, even after prolonged infusions.

- Carfentanil (trade name Wildnil) is an analogue of fentanyl with an analgesic potency 10,000 times that of morphine and is used in veterinary practice to immobilize certain large animals such as elephants.

- Lofentanil is an analogue of fentanyl, with a potency slightly greater than Carfentanil.

A number of other fentanyl analogues exist which are classified in the USA as Schedule I drugs, meaning that they have "no currently accepted medical use".[8] Many of these drugs have been sold on the street as "China White".[9] These drugs include:

- 3-Methylfentanyl (thought to be the active constituent of Kolokol-1, a chemical weapon)

- 3-Methylthiofentanyl

- Acetyl-α-methylfentanyl

- α-methylfentanyl (see below)

- α-methylthiofentanyl

- β-hydroxy-3-methylfentanyl

- β-hydroxyfentanyl

- p-flurorofentanyl

- Thiofentanyl[10]

Therapeutic use

Intravenous fentanyl is extensively used for anesthesia and analgesia, most often in operating rooms and intensive care units. It is often administered in combination with a benzodiazepine, such as midazolam, to produce procedural sedation for endoscopy, cardiac catheterization, oral surgery, etc. Additionally, Fentanyl is often used in cancer therapy and other chronic pain management due to its effectiveness in relieving pain. There is no known opioid better than Fentanyl in reducing cancer pain, which makes it the first choice for use in cancer patients.

Fentanyl transdermal patch (Durogesic/Duragesic/Matrifen) is used in chronic pain management. The patches work by releasing fentanyl into body fats, which then slowly release the drug into the bloodstream over 48 to 72 hours, allowing for long-lasting relief from pain. The patches are available in generic form and are available for lower costs. Fentanyl patches are manufactured in five patch sizes: 12.5 micrograms/hour, 25 µg/h, 50 µg/h, 75 µg/h, and 100 µg/h. Dosage is based on the size of the patch, since the transdermal absorption rate is generally constant at a constant skin temperature. Rate of absorption is dependent on a number of factors. Body temperature, skin type, amount of body fat, and placement of the patch can have major effects. The different delivery systems used by different makers will also affect individual rates of absorption. The typical patch will take effect under normal circumstances usually within 8–12 hours, thus fentanyl patches are often prescribed with another opiate (such as morphine sulfate or oxycodone hydrochloride) to handle breakthrough pain.

Fentanyl lozenges (Actiq) are a solid formulation of fentanyl citrate on a stick in the form of a lollipop that dissolves slowly in the mouth for transmucosal absorption. These lozenges are intended for opioid-tolerant individuals and are effective in treating breakthrough cancer pain. It is also useful for breakthrough pain for those suffering bone injuries, severe back pain, neuropathy, arthritis, and some other examples of chronic nonmalignant pain. The unit is a berry-flavored lozenge on a stick which is swabbed on the mucosal surfaces inside the mouth—inside of the cheeks, under and on the tongue and gums—to release the fentanyl quickly into the system. It is most effective when the lozenge is consumed in 15 minutes. The drug is less effective if swallowed, as despite good absorbance from the small intestine there is extensive first-pass metabolism, leading to an oral bioavailability of 33%. Fentanyl lozenges are available in six dosages, from 200 to 1600 µg in 200 µg increments (excluding 1000 µg and 1400 µg). These are now available in the United states in generic form,[11] through an FTC consent agreement.[12]

However, most patients find it takes 10–15 minutes to use all of one lozenge, and those with a dry mouth cannot use this route. In addition, nurses are unable to document how much of a lozenge has been used by a patient, making drug records inaccurate.

Over 2008-09, a wide range of fentanyl preparations will become available, including buccal tablets or patches, nasal sprays, inhalers and active transdermal patches (heat or electrical). High-quality evidence for their superiority over existing preparations is currently lacking. Some preparations such as nasal sprays and inhalers may result in a rapid response, but the fast onset of high blood levels may compromise safety (see below). In addition, the expense of some of these appliances may greatly reduce their cost-effectiveness.

In palliative care, transdermal fentanyl has a definite, but limited, role for:

- Patients already stabilized on other opioids who have persistent swallowing problem and cannot tolerate other parenteral routes such as subcutaneous administration.

- Patients with moderate to severe renal failure.

- Troublesome adverse effects on morphine, hydromorphone or oxycodone.

Fentanyl is sometimes given intrathecally as part of spinal anesthesia or epidurally for epidural anesthesia and analgesia. Because of fentanyl's high lipid solubility, its effects are more localised than morphine and some clinicians prefer to use the morphine to get a wider spread of analgesia.

Adverse events

Fentanyl's major side effects (more than 10% of patients) include diarrhea, nausea, constipation, dry mouth, somnolence, confusion, asthenia (weakness), and sweating and, less frequently (3 to 10% of patients), abdominal pain, headache, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss, dizziness, nervousness, hallucinations, anxiety, depression, flu-like symptoms, dyspepsia (indigestion), dyspnea (shortness of breath), hypoventilation, apnea, and urinary retention. Fentanyl use has also been associated with aphasia.[13] Fentanyl patch has been associated with altered mental state leading to aggression in an anecdotal case report.[14]

Adverse effects

Like other lipid-soluble drugs, the pharmacodynamics of fentanyl are poorly understood. The manufacturers acknowledge there is no data on the pharmacodynamics of fentanyl in elderly, cachectic or debilitated patients, frequently the type of patient for which transdermal fentanyl is being used. This may explain the increasing number of reports of respiratory depression events since the late 1970s.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21] In 2006 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration started investigating several respiratory deaths, but doctors in the UK had to wait until September 2008 before being warned of the risks with fentanyl.[22]

The precise reason for sudden respiratory depression is unclear, but there are several hypotheses:

- Saturation of the body fat compartment in patients with rapid and profound body fat loss (patients with cancer, cardiac or infection-induced cachexia can lose 80% of their body fat).

- Early carbon dioxide retention causing cutaneous vasodilatation (releasing more fentanyl), together with acidosis which reduces protein binding of fentanyl (releasing yet more fentanyl).

- Reduced sedation, losing a useful early warning sign of opioid toxicity, and resulting in levels closer to respiratory depressant levels.

Fentanyl has a therapeutic index of 270.[23]

Illicit use

Illicit use of pharmaceutical fentanyls first appeared in the mid-1970s in the medical community and continues in the present. United States authorities classify fentanyl as a narcotic. To date, over 12 different analogues of fentanyl have been produced clandestinely and identified in the U.S. drug traffic. The biological effects of the fentanyls are similar to those of heroin, with the exception that many users report a noticeably less euphoric 'high' associated with the drug and stronger sedative and analgesic effects.

Because the effects of fentanyl last for only a very short time, it is even more addictive than heroin, and regular users may become addicted very quickly. Additionally, fentanyl may be hundreds of times more potent than street heroin, and tends to produce significantly worse respiratory depression, making it somewhat more dangerous than heroin to users — though in some places, it is sold as heroin, often leading to overdoses. Fentanyl is most commonly used orally, but like heroin, can also be smoked, snorted or injected. Many fentanyl overdoses are initially classified as heroin overdoses.[25]

Fentanyl is normally sold on the black market in the form of transdermal fentanyl patches such as Duragesic, diverted from legitimate medical supplies. The patches may be cut up and eaten, or the gel from inside the patch smoked. To prevent the removal of the fentanyl base, Janssen-Cilag, the inventor of the Fentanyl patch, designed the Durogesic patch. The Durogesic patches contain their fentanyl throughout the plastic matrix instead of gel incorporated into a reservoir on the patch. Manufacturers such as Mylan have also produced Durogesic-style fentanyl patches that contain the chemical in a silicone matrix, preventing the removal of the fentanyl-containing gel present in other products.

However, the plastic matrix makes the patches far more suitable to transbuccal use and far easier to use illicitly then its gel filled counterpart.[1] Another dosage form of fentanyl that has appeared on the streets are the Actiq fentanyl lollipops, which are sold under the street name of "percopop". The pharmacy retail price ranges from US$10 to US$30 per unit (based on strength of lozenge), with the black market cost anywhere from US$15 to US$40 per unit, depending on the strength.

Non-medical use of fentanyl by individuals without opiate tolerance can be very dangerous and has resulted in numerous deaths.[2] Even those with opiate tolerances are at high risk for overdoses. Once the fentanyl is in the user's system it is extremely difficult to stop its course because of the nature of absorption. Illicitly synthesized fentanyl powder has also appeared on the US market. Because of the extremely high strength of pure fentanyl powder, it is very difficult to dilute appropriately, and often the resulting mixture may be far too strong and consequently very dangerous.

Some heroin dealers mix fentanyl powder with larger amounts of heroin in order to increase potency or compensate for low-quality heroin, and to increase the volume of their product. As of December 2006, a mix of fentanyl and either cocaine or heroin has caused an outbreak in overdose deaths in the United States, heavily concentrated in the cities of Detroit, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Camden, and Chicago,[26] Little Rock, and Dallas.[27] The mixture of fentanyl and heroin is known as "magic" or "the bomb", among other names, on the street.[28]

Several large quantities of illicitly produced fentanyl have been seized by U.S. law enforcement agencies. In June 2006, 945 grams of 83% pure fentanyl powder was seized by Border Patrol agents in California from a vehicle which had entered from Mexico.[29] Mexico is the source of much of the illicit fentanyl for sale in the U.S. However, there has been one domestic fentanyl lab discovered by law enforcement, in April 2006 in Azusa, California. The lab was a source of counterfeit 80-mg OxyContin tablets containing fentanyl instead of oxycodone, as well as bulk fentanyl and other drugs.[30][31]

The "China White" form of fentanyl refers to any of a number of clandestinely produced analogues, especially α-methylfentanyl (AMF)[32][33], which today are classified as Schedule I drugs in the United States.[34] Part of the motivation for AMF is that despite the extra difficulty from a synthetic standpoint, the resultant drug is relatively more resistant to metabolic degradation. This results in a drug with an increased duration.[35]

Overdoses, recalls, and legal action

A number of fatal fentanyl overdoses have been directly tied to the drug over the past several years. In particular, manufacturers of time-release fentanyl patches have come under scrutiny for defective products. While the fentanyl contained in the patches was safe, a malfunction of the patches caused an excessive amount of fentanyl to leak and to be absorbed by patients, resulting in life-threatening side effects and even death.

Manufacturers of fentanyl transdermal pain patches have voluntarily recalled numerous lots of their patches, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued Public Health Advisories related to the fentanyl patch dangers. Manufacturers affected include Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, L.P.; Alza Corporation; Actavis South Atlantic, LLC; Sandoz; and Cephalon, Inc.

On June 19, 2007, a US$5.5 million jury verdict was awarded in a case against Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries Alza Corporation and Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, the manufacturers of the Duragesic fentanyl transdermal pain patch. This case, the first federal trial involving a fentanyl patch, was tried in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida, West Palm Beach Division. Led by attorney Jim Orr, the Dallas, Texas-based law firm Heygood, Orr, Reyes, Pearson & Bartolomei (now Heygood, Orr & Pearson) achieved the verdict for the family of Adam Hendelson, a 28-year-old Florida man, who died while wearing a fentanyl transdermal pain patch.

On November 17, 2008, lead attorneys Jim Orr and Michael Heygood won a case against Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries Alza Corporation and Janssen Pharmaceutica Products in a Cook County Circuit Court, achieving a US$16.5 million jury verdict for the family of 38-year-old Janice DiCosolo, a mother of three who died while wearing the patch in 2004.

Numerous documents from the Dicosolo case and others have been posted in PDF format at the website DangerousDrugs.US

See also

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ http://www.springerlink.com/content/rr47429177364046/

- ^ http://www.drugs.com/pro/sublimaze.html

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19252390

- ^ http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/f/FentanylcitrateinjUSP.htm

- ^ http://www.pauljanssenaward.com/janssen/A_Personal_Perspective.pdf#zoom=100

- ^ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00538863

- ^ 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(1)(B) (2002).

- ^ List of Schedule I Drugs, U.S. Department of Justice.

- ^ List of Schedule I Drugs, U.S. Department of Justice.

- ^ "Barr Launches Generic ACTIQ(R) Cancer Pain Management Product" (Press release). Barr Pharmaceuticals. 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "With Conditions, FTC Allows Cephalon's Purchase of CIMA, Protecting Competition for Breakthrough Cancer Pain Drugs" (Press release). FTC. 2004-08-09. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fentanyl Transdermal Official FDA information, side effects and uses

- ^ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VM1-4S56Y2F-1NR&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=39b136f64677460556bdbb1be8ed7a90

- ^ Smydo J. Delayed respiratory depression with fentanyl. Anesthesia Progress. 26(2):47-8, 1979

- ^ van Leeuwen L. Deen L. Helmers JH. A comparison of alfentanil and fentanyl in short operations with special reference to their duration of action and postoperative respiratory depression. Anaesthesist. 30(8):397-9, 1981

- ^ Brown DL. Postoperative analgesia following thoracotomy. Danger of delayed respiratory depression. Chest. 88(5):779-80, 1985.

- ^ Bulow HH. Linnemann M. Berg H. Lang-Jensen T. LaCour S. Jonsson T. Respiratory changes during treatment of postoperative pain with high dose transdermal fentanyl. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 1995; 39(6): 835-9.

- ^ Nilsson C. Rosberg B. Recurrence of respiratory depression following neurolept analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 26(3):240-1, 1982

- ^ McLoughlin R. McQuillan R. Transdermal fentanyl and respiratory depression. Palliative Medicine, 1997; 11(5):419.

- ^ Regnard C, Pelham A. Severe respiratory depression and sedation with transdermal fentanyl: four case studies. Palliative Medicine, 2003; 17: 714-716.

- ^ Drug Safety Update, vol 2(2) September 2008 p2. Available online on http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Safetyguidance/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON025631

- ^ "New Anesthetic Agents, Devices, and Monitoring Techniques". Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ^ "DEA Microgram Bulletin, June 2006". US Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Forensic Sciences Washington, D.C. 20537. June 2006. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ [Boddiger, D. (2006, August 12). Fentanyl-laced street drugs “kill hundreds”. In EBSCOhost. Retrieved March 7, 2007, from http://proxy.clpccd.cc.ca.us:2271/ehost/ pdf?vid=8&hid=8&sid=e6bcbd34-2854-4beb-bfca-35460dd686e6%40sessionmgr7 ]

- ^ Press Release by the Chicago Police Department Police report about a death linked to heroin/fentanyl mixture August 24, 2006

- ^ SMU student's death blamed on rare drug

- ^ Fentanyl probe nets 3 suspects by Norman Sinclair and Ronald J. Hansen, The Detroit News, June 23, 2006, retrieved June 25, 2006.

- ^ INTELLIGENCE ALERT: HIGH PURITY FENTANYL SEIZED NEAR WESTMORELAND, CALIFORNIA, DEA Microgram, June 2006

- ^ INTELLIGENCE ALERT: LARGE FENTANYL / MDA / TMA LABORATORY IN AZUZA, CALIFORNIA - POSSIBLY THE “OC-80” TABLET SOURCE, DEA Microgram, April 2006.

- ^ INTELLIGENCE ALERT: OXYCONTIN MIMIC TABLETS (CONTAINING FENTANYL) NEAR ATLANTIC, IOWA, DEA Microgram, January 2006.

- ^ List of Schedule I Drugs, U.S. Department of Justice. This DOJ document lists "China White" as a synonym for a number of fentanyl analogues, including 3-methylfentanyl and α-methylfentanyl.

- ^ Behind the Identification of China White Analytical Chemistry, 53(12), 1379A-1386A (1981)

- ^ List of Schedule I Drugs, U.S. Department of Justice.

- ^ Van Bever W, Niemegeers C, Janssen P (1974). "Synthetic analgesics. Synthesis and pharmacology of the diastereoisomers of N-(3-methyl-1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidyl)-N-phenylpropanamide and N-(3-methyl-1-(1-methyl-2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidyl)-N-phenylpropanamide". J Med Chem. 17 (10): 1047–51. doi:10.1021/jm00256a003. PMID 4420811.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- National Institute of Health (NIH) Medline Plus: Fentanyl

- RxList: Fentanyl

- FDA Public Health Advisory: Fentanyl

- US DEA information: fentanyl

- 08/16/2007 News Release: Cephalon Announces Positive Results from a Pivotal Study of FENTORA in Opioid-tolerant Patients with Non-cancer Breakthrough Pain

- Description of use of Fentanyl in Russia as an incapacitating weapon. See also Moscow theater hostage crisis

- BBC news report on Russian siege story

- Lancaster Online story - New Killer: Fentanyl-Heroin Mix

- Fentanyl: Emergency Response Database. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.