Moldavia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

as per consensus on the talk page |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses4| |

{{otheruses4|georgaphical region|the modern state|Moldova}} |

||

{{otheruses4|georgaphical region|the Medieval Principality|Principality of Moldavia}} |

|||

{{otheruses2|Moldova}} |

|||

{{Citations missing|date=January 2007}} |

{{Citations missing|date=January 2007}} |

||

{{Infobox Former Country |

|||

'''Moldavia''' (official: ''Moldova'') is a geographic and historical region corresponding approximatly to the territory of the former [[principality]] in [[Eastern Europe]], between [[Eastern Carpathians]] and [[Dniester]] river. |

|||

|native_name = ''Moldova'' (''Ţara Moldovei'') |

|||

|conventional_long_name = Principality of Moldavia |

|||

|common_name = Moldavia |

|||

|continent = [[Europe]] |

|||

|region = [[South-Eastern Europe]] |

|||

|country = [[Romania]], [[Moldova]], [[Ukraine]] |

|||

|year_start = 1346 |

|||

|year_end = 1862 |

|||

|date_start = |

|||

|date_end = |

|||

|event_start = Foundation of the Moldavian [[Marches|mark]] |

|||

|event_end = ''De Jure'' Union of the [[Danubian Principalities]] |

|||

|p1 = |

|||

|flag_p1 = Possible Moldavian standard, during [[Stephen III of Moldavia|Stephen the Great]] |

|||

|s1 = Romanian Principalities |

|||

|flag_s1 = Flag of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (1859 - 1862).svg |

|||

|image_flag =Flag_of_Moldavia.svg|thumb |

|||

|image_coat = Moldavia CoA.svg |

|||

|image_map = Tara Moldovei map.png |

|||

|image_map_caption = Moldavia and possessions under [[Stephen III of Moldavia|Stephen the Great]], ca. 1500 |

|||

|national_motto = |

|||

|national_anthem = |

|||

|capital = [[Baia]], [[Siret]], [[Suceava]], [[Iaşi]] |

|||

|common_languages = [[Church Slavonic language|Church Slavonic]] (official) |

|||

|government_type = Principality |

|||

|title_leader = [[List of rulers of Moldavia|Princes of Moldavia]] ([[Voivode]]s, [[Hospodar]]s) |

|||

|leader1 = [[Dragoş]] - the first |

|||

|year_leader1 = 1346-1353 |

|||

|leader2 = [[Alexander John Cuza]] - the last |

|||

|year_leader2 = 1859-1862 |

|||

|title_deputy = |

|||

|deputy1 = |

|||

|year_deputy1 = |

|||

|deputy2 = |

|||

|year_deputy2 = |

|||

|stat_year1 = |

|||

|stat_pop1 = |

|||

|stat_year2 = |

|||

|stat_pop2 = |

|||

|stat_year4 = |

|||

|stat_pop4 = |

|||

|stat_area4 = |

|||

|population_density3 = |

|||

|currency = |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Moldavia''' (official: ''Moldova'') is a geographic and historical region and former [[principality]] in [[Eastern Europe]], corresponding to the territory between [[Eastern Carpathians]] and [[Dniester]] river. An initially independent and later autonomous state, it existed from the 14th century to 1859, when it united with [[Wallachia]] as the basis of the modern [[Romania]]n state; at various times, the state included the regions of [[Bessarabia]] (with the [[Budjak]]) and all of [[Bukovina]]. The western part of Moldavia is now part of Romania, the eastern part belongs to the [[Republic of Moldova]], while the northern and south-eastern parts are territories of [[Ukraine]]. |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

| Line 58: | Line 13: | ||

==Name== |

==Name== |

||

{{Main|Etymology of Moldova}} |

{{Main|Etymology of Moldova}} |

||

The names ''Moldavia'' and ''Moldova'' are derived from the name of the [[Moldova River]], however the etymology is not known and there are several variants: |

|||

*a legend featured in ''[[Cronica Anonimă a Moldovei]]'' links it to an [[aurochs]] hunting trip of the [[Maramureş region|Maramureş]] [[voivode]] [[Dragoş]], and the latter's chase of a star-marked bull. Dragoş was accompanied by his female hound called ''Molda''; when they reached shores of an unfamiliar river, Molda caught up with the animal and was killed by it. The dog's name would have been given to the river, and extended to the country. |

*a legend featured in ''[[Cronica Anonimă a Moldovei]]'' links it to an [[aurochs]] hunting trip of the [[Maramureş region|Maramureş]] [[voivode]] [[Dragoş]], and the latter's chase of a star-marked bull. Dragoş was accompanied by his female hound called ''Molda''; when they reached shores of an unfamiliar river, Molda caught up with the animal and was killed by it. The dog's name would have been given to the river, and extended to the country. |

||

| Line 65: | Line 20: | ||

* a [[Slavic languages|Slavic]] etymology (-''ova'' is a quite common Slavic suffix), marking the end of one Slavic genitive form, denoting ownership, chiefly of feminine nouns (i.e.: "that of Molda"). |

* a [[Slavic languages|Slavic]] etymology (-''ova'' is a quite common Slavic suffix), marking the end of one Slavic genitive form, denoting ownership, chiefly of feminine nouns (i.e.: "that of Molda"). |

||

*a landowner by the name of ''Alexa Moldaowicz'' is mentioned in a 1334 document, as a local [[boyar]] in service to [[Boleslaus George II of Halych|Yuriy II of Halych]]; this attests to the use of the name prior to the foundation of the Moldavian state, and could even be the source for the region's name. |

*a landowner by the name of ''Alexa Moldaowicz'' is mentioned in a 1334 document, as a local [[boyar]] in service to [[Boleslaus George II of Halych|Yuriy II of Halych]]; this attests to the use of the name prior to the foundation of the Moldavian state, and could even be the source for the region's name. |

||

In several early references, "Moldavia" is rendered under the composite form ''Moldo-Wallachia'' (in the same way [[Wallachia]] may appear as ''Hungro-Wallachia''). [[Ottoman Turkish language|Ottoman Turkish]] references to Moldavia included ''Boğdan Iflak'' (meaning "[[Bogdan#Rulers of Moldavia|Bogdan]]'s Wallachia") and ''Boğdan'' (and occasionally ''Kara-Boğdan'' - "Black Bogdania"). ''See also: [[List of European regions with alternative names#M|Name in other languages]]''. |

|||

==Flags and coats of arms== |

|||

{{See|Flag and coat of arms of Moldavia}} |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

Image:Moldavian battle flag.jpg|Moldavian 15'th Century battle flag |

|||

image:MoldavianOldCoatWijsbergen.jpg|Coat of arms of the Prince of Moldavia, in the Wijsbergen arms book |

|||

image:Moldova herb.jpg|Coat of arms of the principality of Moldavia, at the Cetăţuia Monastery in Iaşi |

|||

image:MoldavianOldCoatBell.jpg|Coat of arms of the Prince of Moldavia, on the Suceava bell |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==History== |

|||

===Early history=== |

|||

{{Main|Origin of Romanians|Romania in the Dark Ages}} |

|||

In the early 13th century, the ''[[Brodnici|Brodniks]]'', a possible [[Slavic peoples|Slavic]]-[[Vlachs|Vlach]] [[Vassalage|vassal]] state of [[Halych-Volhynia|Halych]], were present, alongside the Vlachs, in much of the region's territory (towards 1216, the Brodniks are mentioned as in service of [[Vladimir-Suzdal|Suzdal]]). On the border between Halych and the Brodniks, in the 11th century, a [[Viking]] by the name of ''Rodfos'' was killed in the area by Vlachs who supposedly betrayed him.[http://www.vikingart.com/VArt/PS_Sjonhem.htm] In 1164, the future [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] [[List of Byzantine Emperors|Emperor]] [[Andronicus I Comnenus]], was taken prisoner by Vlach shepherds around the same region. |

|||

[[Image:Cetate 20CahleTeracotass.png|thumb|Outline of an image on stove remains excavated at the [[Piatra Neamţ]] Fortress, showing the [[Wisent]]/[[Aurochs]] coat of arms of Moldavia and the broken coat of arms of the [[Kingdom of Hungary]].]] |

|||

===Foundation of the principality=== |

|||

: ''Main article: [[Foundation of Moldavia]]'' |

|||

Later in the 13th century, [[King of Hungary|King]] [[Charles I of Hungary|Charles I]] of [[Kingdom of Hungary|Hungary]] attempted to expand his realm and the influence of the [[Roman Catholic Church]] eastwards after the fall of Cuman rule, and ordered a campaign under the command of [[Phynta de Mende]] (1324). In 1342 and 1345, the Hungarians were victorious in a battle against [[Tatars]]; the conflict was resolved by the death of [[Jani Beg]], in 1357). The [[Poland|Polish]] [[chronicle]]r [[Jan Długosz]] mentioned Moldavians (under the name ''Wallachians'') as having joined a military expedition in 1342, under [[List of Polish monarchs|King]] [[Władysław I the Elbow-high|Władysław I]], against the [[Margraviate of Brandenburg]].<ref>''The Annals of Jan Długosz'', p. 273</ref> |

|||

In 1353, [[Dragoş]], mentioned as a Vlach ''[[Knyaz]]'' in [[Maramureş region|Maramureş]], was sent by [[Louis I of Hungary|Louis I]] to establish a line of defense against the Golden Horde forces on the [[Siret River]]. This expedition resulted in a polity vassal to Hungary, centered around [[Baia]] (''Târgul Moldovei'' or ''Moldvabánya''). |

|||

[[Bogdan I of Moldavia|Bogdan of Cuhea]], another Vlach [[voivode]] from Maramureş who had fallen out with the Hungarian king, crossed the Carpathians in 1359, took control of Moldavia, and succeeded in removing Moldavia from Hungarian control. His realm extended north to the [[Cheremosh River]], while the southern part of Moldavia was still occupied by the Tatars. |

|||

After first residing in Baia, Bogdan moved Moldavia's seat to [[Siret]] (it was to remain there until [[Petru Muşat]] moved it to [[Suceava]]; it was finally moved to [[Iaşi]] under [[Alexandru Lăpuşneanu]] - in 1565). The area around Suceava, roughly correspondent to [[Bukovina]], formed one of the two administrative divisions of the new realm, under the name ''Ţara de Sus'' (the "Upper Land"), whereas the rest, on both sides of the [[Prut River]], formed ''Ţara de Jos'' (the "Lower Land"). |

|||

Disfavored by the brief union of [[History of Poland (966–1385)|Angevin Poland]] and Hungary (the latter was still the country's [[overlord]]), Bogdan's successor [[Laţcu of Moldavia|Laţcu]] accepted [[Religious conversion|conversion]] to [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholicism]] around 1370, but his gesture was to remain without consequences. Despite remaining officially [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Eastern Orthodox]] and culturally connected with the [[Byzantine Empire]] after 1382, princes of the [[Muşatin family]] entered a conflict with the [[Patriarch of Constantinople|Constantinople Patriarchy]] over control of appointments to the newly-founded [[Metropolitan of Moldavia|Moldavian Metropolitan seat]]; [[Patriarch Anthony IV of Constantinople|Patriarch Anthony IV]] even cast an [[anathema]] over Moldavia after [[Roman I of Moldavia|Roman I]] expelled his appointee back to Byzantium. The crisis was finally settled in favor of the Moldavian princes under [[Alexandru cel Bun]]. Nevertheless, religious policy remained complex: while conversions to faiths other than Orthodox were discouraged (and forbidden for princes), Moldavia included sizable Roman Catholic communities ([[Germans]] and [[Magyars|Hungarians]]), as well as [[Armenian Apostolic Church|non-Chalcedonic]] [[Armenians in Romania|Armenians]]; after 1460, the country welcomed [[Hussite]] refugees (founders of [[Ciuburciu]] and, probably, [[Huşi]]). |

|||

===Early Muşatin rulers=== |

|||

{{main|Romania in the Middle Ages}} |

|||

The principality of Moldavia covered the entire geographic region of Moldavia. In various periods, various other territories were politically connected with the Moldavian pricipality. This is the case of the province of [[Pokuttya]], the fiefdoms of [[Cetatea de Baltă]] and [[Ciceu]] (both in [[Transylvania]]) or, at a later date, the territories between the Dniester and the Bug Rivers. |

|||

[[Petru I of Moldavia|Petru I]] profited from the end of the Hungarian-Polish union, and moved the country closer to the [[History of Poland (1385–1569)|Jagiellon realm]], becoming a [[Vassalage|vassal]] of [[Władysław II Jagiełło|Władysław II]] on [[September 26]], [[1387]]. This gesture was to have unexpected consequences: Petru supplied the Polish ruler with funds needed in the war against the [[Teutonic Knights]], and was granted control over [[Pokuttya]] until the debt was to be repaid; as this is not recorded to have been carried out, the region became disputed by the two states, until it was lost by Moldavia in the [[Battle of Obertyn]] (1531). Prince Petru also expanded his rule southwards to the [[Danube Delta]], and established a frontier with [[Wallachia]]{{Fact|date=January 2007}}; his son Roman I conquered the Hungarian-ruled [[Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi|Cetatea Albă]] in 1392, giving Moldavia an outlet to the [[Black Sea]], before being toppled from the throne for supporting [[Theodor Koriatovich]] in his conflict with [[Vytautas the Great]] of [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania|Lithuania]]. Under [[Stephen I of Moldavia|Stephen I]], growing Polish influence was challenged by [[Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor|Sigismund of Hungary]], whose expedition was defeated at [[Ghindăoani]] in 1385; however, Stephen disappeared in mysterious circumstances, and the throne was soon occupied by [[Iuga of Moldavia|Yury Koriatovich]]{{Fact|date=January 2007}} (Vytautas' favorite). |

|||

[[Alexandru cel Bun]], although brought to the throne in 1400 by the Hungarians (with assistance from [[Mircea I of Wallachia]]), shifted his allegiances towards Poland (notably engaging Moldavian forces on the Polish side in the [[Battle of Grunwald]] and the [[Siege of Marienburg (1410)|Siege of Marienburg]]), and placed his own choice of rulers in Wallachia. His reign was one of the most successful in Moldavia's history, but also saw the very first confrontation with the [[Ottoman Turks]] at Cetatea Albă in 1420, and later even a conflict with the Poles. A deep crisis was to follow Alexandru's long reign, with his successors battling each other in a succession of wars that divided the country until the murder of [[Bogdan II of Moldavia|Bogdan II]] and the ascension of [[Petru Aron]] in 1451. Nevertheless, Moldavia was subject to further Hungarian interventions after that moment, as [[Matthias Corvinus of Hungary|Matthias Corvinus]] deposed Aron and backed [[Alexăndrel]] to the throne in [[Suceava]]. Petru Aron's rule also signified the beginning of Moldavia's [[Ottoman Empire]] allegiance, as the ruler agreed to pay [[tribute]] to [[Ottoman Dynasty|Sultan]] [[Mehmed II]]. |

|||

Under [[Stephen III of Moldavia|Stephen the Great]], who took the throne and subsequently came to an agreement with [[Kazimierz IV Jagiellon|Kazimierz IV of Poland]] in 1457, the state reached its most glorious period. Stephen blocked Hungarian interventions in the [[Battle of Baia]], invaded Wallachia in 1471, and dealt with Ottoman reprisals in a major victory (the 1475 [[Battle of Vaslui]]; after feeling threatened by Polish ambitions, he also attacked [[Galicia (Central Europe)|Galicia]] and resisted Polish reprisals in the [[Battle of the Cosmin Forest]] (1497). However, he had to surrender [[Kiliya|Chilia]] (Kiliya) and [[Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyi|Cetatea Albă]] (Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyi), the two main fortresses in the [[Bujak]], to the Ottomans in 1484, and in 1498 he had to accept Ottoman suzereignty, when he was forced to agree to continue paying tribute to Sultan [[Bayezid II]]. Following the taking of [[Khotyn]] and [[Pokuttya]], Stephen's rule also brought a brief extension of Moldavian rule into [[Transylvania]]: [[Cetatea de Baltă]] and [[Ciceu]] became his [[Fiefdom|fiefs]] in 1489. |

|||

Under [[Bogdan III cel Orb]], Ottoman overlordship was confirmed in the shape that would rapidly evolve into control over Moldavia's affairs. [[Petru Rareş]], who reigned in the 1530s and 1540s, clashed with the [[Habsburg Monarchy]] over his ambitions in Transylvania (losing possessions in the region to [[George Martinuzzi]]), was defeated in Pokuttya by Poland, and failed in his attempt to extricate Moldavia from Ottoman rule – the country lost [[Bender, Moldova|Bender]] to the Ottomans, who included it in their [[Silistra Province, Ottoman Empire|Silistra]] ''[[Subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire|eyalet]]''. |

|||

===Renaissance Moldavia=== |

|||

{{Main|Early Modern Romania}} |

|||

A period of profound crisis followed. Moldavia stopped issuing its own coinage circa 1520, under Prince [[Ştefăniţă]], when it was confronted with rapid depletion of funds and rising demands from the [[Porte]]. Such problems became endemic when the country, brought into the [[Great Turkish War]], suffered the impact of the [[Stagnation of the Ottoman Empire]]; at one point, during the 1650s and 1660s, princes began relying on [[counterfeit]] coinage (usually copies of [[Swedish riksdaler]]s, as was that issued by [[Eustratie Dabija]]). The economic decline was accompanied by a failure to maintain state structures: the [[Feudalism|feudal]]-based [[Moldavian military forces]] were no longer convoked, and the few troops maintained by the rulers remained professional [[Mercenary|mercenaries]] such as the ''[[seimeni]]''. |

|||

However, Moldavia and the similarly-affected Wallachia remained both important sources of income for the Ottoman Empire and relatively prosperous agricultural economies (especially as suppliers of grain and cattle – the latter was especially relevant in Moldavia, which remained an under-populated country of [[pasture]]s). In time, much of the resources were tied to the [[Economic history of the Ottoman Empire|Ottoman economy]], either through [[Monopoly|monopolies]] on trade which were only lifted in 1829, after the [[Treaty of Adrianople]] (which did not affect all domains directly), or through the raise in direct [[tax]]es - the one demanded by the Ottomans from the princes, as well as the ones demanded by the princes from the country's population. Taxes were directly proportional with Ottoman requests, but also with the growing importance of Ottoman appointment and sanctioning of princes in front of election by the [[boyars]] and the boyar Council – ''[[Sfatul boieresc]]'' (drawing in a competition among pretenders, which also implied the intervention of creditors as suppliers of [[bribe]]s). The fiscal system soon included taxes such as the ''văcărit'' (a tax on head of cattle), first introduced by [[Iancu Sasul]] in the 1580s. |

|||

The economic opportunities offered brought about a significant influx of [[Greeks in Romania|Greek]] and [[Levant]]ine financiers and officials, who entered a stiff competition with the high boyars over appointments to the Court. As the [[Manorialism|manor system]] suffered the blows of economic crises, and in the absence of [[Salary|salarisation]] (which implied that persons in office could decide their own income), obtaining princely appointment became the major focus of a boyar's career. Such changes also implied the decline of free peasantry and the rise of [[serfdom]], as well as the rapid fall in the importance of low boyars (a traditional institution, the latter soon became marginal, and, in more successful instances, added to the population of towns); however, they also implied a rapid transition towards a [[monetary economy]], based on exchanges in foreign currency. Serfdom was doubled by the much less numerous [[Slavery|slave]] population, comprised of migrant [[Roma minority in Romania|Roma]] and captured [[Nogais]]. |

|||

The conflict between princes and boyars was to become exceptionally violent – the latter group, who frequently appealed to the Ottoman court in order to have princes comply with its demands, was persecuted by rulers such as [[Alexandru Lăpuşneanu]] and [[Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit]]. Ioan Vodă's revolt against the Ottomans ended in his execution (1574). The country descended into political chaos, with frequent Ottoman and [[Tatars|Tatar]] incursions and pillages. The claims of Muşatins to the crown and the traditional system of succession were ended by scores of illegitimate reigns; one of the usurpers, [[Ioan Iacob Heraclid]], was a [[Protestantism|Protestant]] Greek who encouraged the [[Renaissance]] and attempted to introduce [[Lutheranism]] to Moldavia. |

|||

[[Image:Mihai 1600.png|thumb|250px|left|Moldavia (in orange) towards the end of the 16th century]] |

|||

In 1595, the rise of the [[Movileşti]] boyars to the throne with [[Ieremia Movilă]] coincided with the start of frequent anti-Ottoman and anti-[[Habsburg Monarchy|Habsburg]] military expeditions of the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] into Moldavian territory (see ''[[Moldavian Magnate Wars]]''), and rivalries between pretenders to the Moldavian throne encouraged by the three competing powers. The Wallachian prince [[Michael the Brave]] deposed Prince Ieremia in 1600, and managed to become the very first monarch to unite Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania under his rule; the episode ended in Polish conquests of lands down to [[Bucharest]], soon ended by the outbreak of the [[Polish-Sweden War (1600-1611)|Polish-Swedish War]] and the reestablishment of Ottoman rule. Polish incursions were dealt a blow by the Ottomans during the 1620 [[Battle of Cecora (1620)|Battle of Cecora]], which also saw an end to the reign of [[Gaspar Graziani]]. |

|||

The following period of relative peace saw the more prosperous and prestigious rule of [[Vasile Lupu]], who took the throne as a boyar appointee in 1637, and began battling his rival [[Gheorghe Ştefan]], as well as the Wallachian prince [[Matei Basarab]] – however, his invasion of Wallachia with the backing of [[Cossack]] [[Hetmans of Ukrainian Cossacks|Hetman]] [[Bohdan Khmelnytsky]] ended in disaster at the [[Battle of Finta]] (1653). A few years later, Moldavia was occupied for two short intervals by the anti-Ottoman Wallachian prince [[Constantin Şerban]], who clashed with the first ruler of the [[Ghica family]], [[Gheorghe Ghica]]. In the early 1680s, Moldavian troops under [[George Ducas]] intervened in [[Right-bank Ukraine]] and assisted [[Mehmed IV]] in the [[Battle of Vienna]], only to suffer the effects of the [[Great Turkish War]]. |

|||

===18th century=== |

|||

{{Main|Phanariotes|History of the Russo-Turkish wars}} |

|||

During the late 17th century, Moldavia became the target of the [[Imperial Russia|Russian Empire]]'s southwards expansion, inaugurated by [[Peter I of Russia|Peter the Great]] during the [[Russo-Turkish War, 1710-1711|Russo-Turkish War of 1710-1711]]; Prince [[Dimitrie Cantemir]]'s siding with Peter and open anti-Ottoman rebellion, ended in defeat at [[Stănileşti]], provoked Sultan [[Ahmed III]]'s reaction, and the official discarding of recognition of local choices for princes, imposing instead a system which relied solely on Ottoman approval – the [[Phanariotes|Phanariote epoch]], inaugurated by the reign of [[Nicholas Mavrocordatos]]. Short and frequently ended through violence, Phanariote rules were usually marked by [[political corruption]], intrigue, and high taxation, as well as by sporadic incursions of Habsburg and Russian armies deep into Moldavian territory; nonetheless, they also saw attempts at legislative and administrative modernization inspired by [[Age of Enlightenment|The Enlightenment]] (such as [[Constantine Mavrocordatos]]' decision to salirize public offices, to the outrage of boyars, and the abolition of serfdom in 1749, as well as [[Scarlat Callimachi]]'s ''Code''), and signified a decrease in Ottoman demands after the threat of Russian annexation became real and the prospects of a better life led to waves of peasant emigration to neighboring lands. The effects of Ottoman control were also made less notable after the 1774 [[Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca]] allowed Russia to intervene in favor of Ottoman subjects of the Eastern Orthodox faith - leading to campaigns of [[petition]]ing by the Moldavian boyars against princely politics. |

|||

In 1712, [[Khotyn]] was taken over by the Ottomans, and became part of a defensive system that Moldavian princes were required to maintain, as well as an area for [[Islam]]ic [[colonization]] (the [[Laz people|Laz]] community). Moldavia also lost [[Bukovina]], [[Suceava]] included, to the Habsburgs in 1772, which meant both an important territorial loss and a major blow to the cattle trade (as the region stood on the trade route to [[Central Europe]]). The 1792 [[Treaty of Jassy]] forced the Ottoman Empire to cede all of its holdings in what is now [[Transnistria]] to Russia, which made Russian presence much more notable, given that the Empire acquired a common border with Moldavia. The first effect of this was the cession of [[Bessarabia]] to the Russian Empire, in 1812 (through the [[Treaty of Bucharest, 1812|Treaty of Bucharest]]). |

|||

===Organic Statute, revolution, and union with Wallachia=== |

|||

{{Main|National awakening of Romania}} |

|||

[[Image:Rom1793-1812.png|thumb|250px|right|Principality of Moldavia, 1793-1812, highlighted in orange]] |

|||

Phanariote rules were officially ended after the 1821 occupation of the country by [[Alexander Ypsilantis (1792-1828)|Alexander Ypsilantis]]' [[Filiki Eteria]] during the [[Greek War of Independence]]; the subsequent Ottoman retaliation brought the rule of [[Ioan Sturdza]], considered as the first one of a new system – especially since, in 1826, the Ottomans and Russia agreed to allow for the election by locals of rulers over the two [[Danubian Principalities]], and convened on their mandating for seven-year terms. In practice, a new fundament to reigns in Moldavia was created by the [[Russo-Turkish War, 1828-1829|Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829]], and a period of Russian domination over the two countries which ended only in 1856: begun as a military occupation under the command of [[Pavel Kiselyov]], Russian domination gave Wallachia and Moldavia, which were not removed from nominal Ottoman control, the modernizing ''[[Regulamentul Organic|Organic Statute]]'' (the first document resembling a [[constitution]], as well as the first one to regard both principalities). After 1829, the country also became an important destination for [[immigration]] of [[Ashkenazi Jews]] from the [[Galicia (Central Europe)|Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria]] and areas of Russia (''see [[History of the Jews in Romania]] and [[Sudiţi]]''). |

|||

The first Moldavian rule established under the Statute, that of [[Mihail Sturdza]], was nonetheless ambivalent: eager to reduce abuse of office. Sturdza introduced reforms (the abolition of slavery, [[secularization]], economic rebuilding), but he was widely seen as enforcing his own power over that of the newly-instituted consultative Assembly. A supporter of the union of his country with Wallachia and of [[Romanians|Romanian]] [[Romantic nationalism]], he obtained the establishment of a [[customs union]] between the two countries (1847) and showed support for [[Radicalism (historical)|radical]] projects favored by low boyars; nevertheless, he clamped down with noted violence the [[1848 Wallachian revolution|Moldavian revolutionary attempt]] in the last days of March 1848. [[Grigore Alexandru Ghica]] allowed the exiled revolutionaries to return to Moldavia cca. 1853, which led to the creation of ''[[Partida Naţională]]'' (the “National Party”), a trans-boundary group of radical union supporters which campaigned for a single state under a foreign dynasty. |

|||

[[Image:Rom1856-1859.png|thumb|250px|left|Moldavia (in orange) between 1856 and 1859]] |

|||

Russian domination ended abruptly after the [[Crimean War]], when the [[Treaty of Paris (1856)|Treaty of Paris]] passed the two principalities under the tutelage of [[Great power|Great European Powers]] (together with Russia and the Ottoman overlord, power-sharing included the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland]], the [[Austrian Empire]], the [[Second French Empire|French Empire]], the [[Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia]], and [[Prussia]]). Due to Austrian and Ottoman opposition and British reserves, the union program as demanded by radical campaigners was debated intensely. In September 1857, given that ''[[Kaymakam|Caimacam]]'' [[Nicolae Vogoride]] had perpetrated [[Electoral fraud|fraud]] in elections in Moldavia in July,{{Fact|date=January 2007}} the Powers allowed the two states to convene ''[[Ad-hoc divans]]'', which were to decide a new constitutional framework; the result showed overwhelming support for the union, as the creation of a [[Liberalism|liberal]] and [[Neutral country|neutral]] state. After further meetings among leaders of tutor states, an agreement was reached (the ''Paris Convention''), whereby a limited union was to be enforced – separate governments and thrones, with only two bodies (a [[High Court of Cassation and Justice|Court of Cassation]] and a Central Commission residing in [[Focşani]]; it also stipulated that an end to all [[privilege]] was to be passed into law, and awarded back to Moldavia the areas around [[Bolhrad]], [[Cahul]], and [[Izmail]]. |

|||

However, the Convention failed to note whether the two thrones could not be occupied by the same person, allowing ''Partida Naţională'' to introduce the candidacy of [[Alexander John Cuza]] in both countries. On [[January 17]] ([[January 5]], [[1859]] [[Old Style and New Style dates|Old Style]]), he was elected prince of Moldavia by the respective electoral body. After street pressure over the much more [[Conservatism|conservative]] body in [[Bucharest]], Cuza was elected in Wallachia as well ([[February 5]]/[[January 24]]). Exactly three years later, after diplomatic missions that helped remove opposition to the action, the formal union created [[Romania]] and instituted Cuza as ''[[Domnitor]]'' (all legal matters were clarified after the replacement of the prince with [[Carol I of Romania|Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen]] in April 1866, and the creation of an independent [[Kingdom of Romania]] in 1881) - this officially ending the existence of the Principality of Moldavia. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 17:12, 9 August 2008

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2007) |

Moldavia (official: Moldova) is a geographic and historical region corresponding approximatly to the territory of the former principality in Eastern Europe, between Eastern Carpathians and Dniester river.

Geography

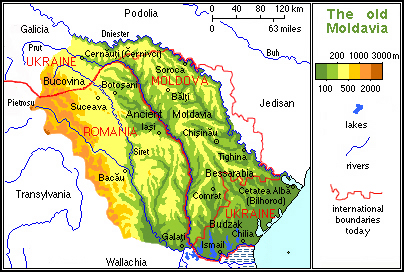

Geographically, Moldavia is limited by the Carpathian Mountains to the West, the Cheremosh River to the North, the Dniester River to the East and the Danube and Black Sea to the South. The Prut River flows approximately through its middle from north to south. Of early 15th century Moldavia, the biggest part is located in Romania (42%), followed by the Republic of Moldova (33%) and Ukraine (25%). This represents 90.5% of Moldova's surface and 19.5% of Romania's surface.

The region is mostly hilly, with a range of mountains in the west, and plain areas in the southeast. Moldavia's highest altitude is Ineu peak (2,279m), which is also the westernmost point of the region.

Name

The names Moldavia and Moldova are derived from the name of the Moldova River, however the etymology is not known and there are several variants:

- a legend featured in Cronica Anonimă a Moldovei links it to an aurochs hunting trip of the Maramureş voivode Dragoş, and the latter's chase of a star-marked bull. Dragoş was accompanied by his female hound called Molda; when they reached shores of an unfamiliar river, Molda caught up with the animal and was killed by it. The dog's name would have been given to the river, and extended to the country.

- the old German Molde, meaning "open-pit mine"

- the Gothic Mulda meaning "dust", "dirt" (cognate with the English mould), referring to the river.

- a Slavic etymology (-ova is a quite common Slavic suffix), marking the end of one Slavic genitive form, denoting ownership, chiefly of feminine nouns (i.e.: "that of Molda").

- a landowner by the name of Alexa Moldaowicz is mentioned in a 1334 document, as a local boyar in service to Yuriy II of Halych; this attests to the use of the name prior to the foundation of the Moldavian state, and could even be the source for the region's name.

See also

- Bessarabia

- Bukovina

- History of Moldova

- History of Romania

- List of rulers of Moldavia

- Moldavian military forces

- Painted churches of northern Moldavia

References

- Gheorghe I. Brătianu, Sfatul domnesc şi Adunarea Stărilor în Principatele Române, Bucharest, 1995

- Vlad Georgescu, Istoria ideilor politice româneşti (1369-1878), Munich, 1987

- Ştefan Ştefănescu, Istoria medie a României, Bucharest, 1991

External links

- Dimitrie Cantemir-Descrierea Moldovei

- The Princely Court in Bacău - images, layouts (at the Romanian Group for an Alternative History Website)

- Original Documents concerning both Moldavia and other Romania Principalities during the Middle Ages (at the Romanian Group for an Alternative History Website)

- Pilgrimage and Cultural Heritage Tourism in Moldavia

- Painted Churches in Bukovina