Nymph

A nymph in Greek mythology is a minor nature goddess typically associated with a particular location or landform. Other nymphs, always in the shape of young nubile maidens, were part of the retinue of a god, such as Dionysus, Hermes, or Pan, or a goddess, generally Artemis.[1] Nymphs were the frequent target of satyrs. They live in mountains and groves, by springs and rivers, and also in trees and in valleys and cool grottoes. They are frequently associated with the superior divinities: the huntress Artemis; the prophetic Apollo; the reveller and god of wine, Dionysus; and rustic gods such as Pan and Hermes.

The symbolic marriage of a nymph and a patriarch, often the eponym of a people, is repeated endlessly in Greek origin myths; their union lent authority to the archaic king and his line.

Etymology

Nymphs are personifications of the creative and fostering activities of nature, most often identified with the life-giving outflow of springs: as Walter Burkert (Burkert 1985:III.3.3) remarks, "The idea that rivers are gods and springs divine nymphs is deeply rooted not only in poetry but in belief and ritual; the worship of these deities is limited only by the fact that they are inseparably identified with a specific locality."

The Greek word νύμφη has "bride" and "veiled" among its meanings: hence a marriageable young woman. Other readers refer the word (and also Latin nubere and German Knospe) to a root expressing the idea of "swelling" (according to Hesychius, one of the meanings of νύμφη is "rose-bud").

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Nymphs |

Adaptations

The Greek nymphs were spirits invariably bound to places, not unlike the Latin genius loci, and the difficulty of transferring their cult may be seen in the complicated myth that brought Arethusa to Sicily. In the works of the Greek-educated Latin poets, the nymphs gradually absorbed into their ranks the indigenous Italian divinities of springs and streams (Juturna, Egeria, Carmentis, Fontus), while the Lymphae (originally Lumpae), Italian water-goddesses, owing to the accidental similarity of their names, could be identified with the Greek Nymphae. The mythologies of classicizing Roman poets were unlikely to have affected the rites and cult of individual nymphs venerated by country people in the springs and clefts of Latium. Among the Roman literate class, their sphere of influence was restricted, and they appear almost exclusively as divinities of the watery element.

In modern Greek folklore

The ancient Greek belief in nymphs survived in many parts of the country into the early years of the twentieth century, when they were usually known as "nereids". At that time, John Cuthbert Lawson wrote: "...there is probably no nook or hamlet in all Greece where the womenfolk at least do not scrupulously take precautions against the thefts and malice of the nereids, while many a man may still be found to recount in all good faith stories of their beauty, passion and caprice. Nor is it a matter of faith only; more than once I have been in villages where certain Nereids were known by sight to several persons (so at least they averred); and there was a wonderful agreement among the witnesses in the description of their appearance and dress."[2]

Nymphs tended to frequent areas distant from humans but could be encountered by lone travellers outside the village, where their music might be heard, and the traveller could spy on their dancing or bathing in a stream or pool, either during the noon heat or in the middle of the night. They might appear in a whirlwind. Such encounters could be dangerous, bringing dumbness, besotted infatuation, madness or stroke to the unfortunate human. When parents believed their child to be nereid-struck, they would pray to Saint Artemidos, the Christian manifestation of Artemis.[3][4]

Modern sexual connotations

Due to the depiction of the mythological nymphs as females who mate with men or women at their own volition, the term is often used for women who are perceived as behaving similarly. (For example, the title of the Perry Mason detective novel The Case of the Negligent Nymph (1956) by Erle Stanley Gardner is derived from this meaning of the word.)

The term nymphomania was created by modern psychology as referring to a "desire to engage in human sexual behavior at a level high enough to be considered clinically significant", nymphomaniac being the person suffering from such a disorder. Due to widespread use of the term among lay persons (often shortened to nympho) and stereotypes attached, professionals nowadays prefer the term hypersexuality, which can refer to males and females alike.

The word nymphet is used to identify a sexually precocious girl. The term was made famous in the novel Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. The main character, Humbert Humbert, uses the term countless times, usually in reference to the title character.

Classification

As H.J. Rose states, all the names for various classes of nymphs are plural feminine adjectives agreeing with the substantive nymphai, and there was no authentic classification that could be seen as canon and exhaustive[5]. The classes of nymphs tend to overlap, which complicates the task of precise classification.

The following[6] is not the Greek classification, but is intended simply as a guide:

- Celestial nymphs

- Aurae (breezes), also called Aetae or Pnoae

- Asteriae (stars), mainly comprising the Atlantides (daughters of Atlas)

- Hesperides (nymphs of the West, daughters of Atlas; also had attributes of the Hamadryads)

- Hyades (star cluster; sent rain)

- Pleiades (daughters of Atlas and Pleione; constellation; also were classed as Oreads)

- Nephelae (clouds)

- Land nymphs

- Alseides (glens, groves)

- Auloniades (pastures)

- Leimakides or Leimonides (meadows)

- Napaeae (mountain valleys, glens)

- Oreads (mountains, grottoes), also Orodemniades

- Wood and plant nymphs

- Anthousai (flowers)

- Dryades (trees)

- Hamadryades or Hadryades

- Hyleoroi (watchers of woods)

- Water nymphs (Hydriades or Ephydriades)

- Heleades (fen)

- Haliae (sea and seashores)

- Nereids (50 daughters of Nereus, the Mediterranean Sea)

- Naiads or Naides (fresh water)

- Crinaeae (fountains)

- Eleionomae (marshes)

- Limnades or Limnatides (lakes)

- Pegaeae (springs)

- Potameides (rivers)

- Oceanids (daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, any water, usually salty)

- see List of Oceanids

- Underworld nymphs

- Other nymphs

- Hecaterides (rustic dance) - sisters of the Dactyls, mothers of the Oreads and the Satyrs

- Kabeirides - sisters of the Kabeiroi

- Maenads or Bacchai or Bacchantes - frenzied nymphs in the retinue of Dionysus

- Lenai (wine-press)

- Mimallones (music)

- Naides (Naiads)

- Thyiai or Thyiades (thyrsus bearers)

- Melissae (honey bees), likely a subgroup of Oreades or Epimelides

- The Muses (memory, knowledge, art)

- Themeides - daughters of Zeus and Themis, prophets and keepers of certain divine artefacts

- Location-specific groupings of nymphs[7]

- Aeaean Nymphs (Aeaea Island), handmaidens of Circe

- Aegaeides (Aegaeus River on the island of Scheria)

- Aesepides (Aesepus River in Anatolia)

- Acheloides (Achelous River)

- Acmenes (Stadium in Olympia, Elis)

- Amnisiades (Amnisos River on the island of Crete), who entered the retinue of Artemis

- Anigrides (Anigros River in Elis), who were believed to cure skin diseases

- Asopides (Asopus River in Sicyonia and Boeotia)

- Astakides (Lake Astakos in Bithynia)

- Asterionides (Asterion River) - nurses of Hera

- Carian Naiades (Caria)

- Nymphs of Ceos

- Corycian Nymphs (Corycian Cave)

- Cydnides (River Cydnus in Cilicia)

- Cyrenaean Nymphs (City of Cyrene, Libya)

- Cypriae Nymphs (Island of Cyprus)

- Cyrtonian Nymphs (Town of Cyrtone, Boeotia)

- Deliades (Island of Delos) - daughters of the river god Inopos

- Dodonides (Oracle at Dodona)

- Erasinides (Erasinos River in Argos), followers of Britomartis

- Anchiroe

- Byze

- Maira

- Melite

- Heliades (River Eridanos) - daughters of Helios who were changed into trees

- Himeriai Naiades (Local springs at the town of Himera, Sicily)

- Hydaspides (River Hydaspes in India), nurses of infant Zagreus

- Idaean Nymphs (Mount Ida), nurses of infant Zeus

- Ida

- Adrastea

- Inachides (Inachus River)

- Amymone

- Automate

- Hippe

- Hyperia

- Messeis

- Physadeia

- Ionides (Kytheros River in Elis)

- Calliphaea

- Iasis

- Pegaea

- Synallaxis

- Ithacian Nymphs (Local springs on the island of Ithaca)

- Ladonides (Ladon River)

- Lamides (Lamos River in Cilicia)

- Leibethrides (Mounts Helicon and Leibethrios in Boeotia; or Mount Leibethros in Thrace)

- Libethrias

- Petra

- Lelegeides (Lycia, Anatolia)

- Lycaean Nymphs (Mount Lycaeus), nurses of infant Zeus, perhaps a subgroup of the Oceanides

- Melian Nymphs (Island of Melos), transformed into frogs by Zeus; not to be confused with the Meliae (ash tree nymphs)

- Mycalessides (Mount Mycale in Caria, Anatolia)

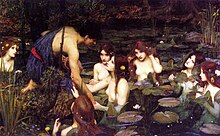

- Mysian Nymphs (Spring of Pegai near Lake Askanios in Bithynia), who abducted Hylas

- Naxian Nymphs (Mount Drios on the island of Naxos), nurses of infant Dionysus; syncretized with the Hyades

- Nymphaeides (Nymphaeus River in Paphlagonia)

- Nysiads (Mount Nysa) - nurses of infant Dionysos, identified with Hyades

- Ogygian Nymphs (Island of Ogygia), four handmaidens of Calypso

- Ortygian Nymphs (Local springs of Syracuse, Sicily), named for the island of Ortygia

- Othreides (Mount Othrys), a local group of Hamadryads

- Pactolides (Pactolus River)

- Euryanassa, wife of Tantalus

- Pelionides (Mount Pelion), nurses of the Centaurs

- Phaethonides, a synonym for the Heliades

- Phaseides (Phasis River)

- Rhyndacides (Rhyndacus River in Mysia, Anatolia)

- Sithnides (Fountain at the town of Megara)

- Spercheides (River Spercheios); one of them, Diopatra, was loved by Poseidon and the others were changed by him into trees

- Sphragitides (Mount Cithaeron)

- Thessalides (Peneus River in Thessaly)

- Thriae (Mount Parnassos), prophets and nurses of Apollo

- Trojan Nymphs (Local springs of Troy)

- Individual names of some of the nymphs

- Sabrina (the river Severn)

See also

- Animism

- Apsaras

- Calypso

- Castalia

- Elizabeth Elstob, "The Saxon Nymph"

- Fairy

- Genius loci

- Houri

- Huacas

- Kami

- Landvaettir

- Lampades

- Melusine

- List of Greek mythological figures#Nymphs

- Nymphs and Satyr (painting)

- The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd by Sir Walter Raleigh

- Nymphenburg ("Nymph's Castle"), palace in Munich

- Ondine (mythology)

- Pitsa panels

- Psychai

- Rå

- Siren

- Slavic fairies

- Sprite (creature)

- Succubus

- Yakshini

References

- ^ But see Jennifer Larson, "Handmaidens of Artemis?", The Classical Journal 92.3 (February 1997), pp. 249-257.

- ^ Lawson, John Cuthbert (1910). Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 131.

- ^ "heathen Artemis yielded her functions to her own genitive case transformed into Saint Artemidos", as Terrot Reaveley Glover phrased it in discussing the "practical polytheimism in the worship of the saints", in Progress in Religion to the Christian Era 1922:107.

- ^ Tomkinson, John L. (2004). Haunted Greece: Nymphs, Vampires and Other Exotika (1st ed.). Athens: Anagnosis. chapter 3. ISBN 960-88087-0-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Rose, Herbert Jennings (1959). A Handbook of Greek Mythology (1st ed.). New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. p. 173. ISBN 0-525-47041-7.

- ^ Theoi Project - Classification of Nymphs

- ^ [http://www.theoi.com/Cat_Nymphai.html Theoi Project - List of Nymphs

Sources

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36281-0.

- Larson, Jennifer Lynn (2001). Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195144651.

- Lawson, John Cuthbert, Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1910, p. 131

- Nereids

- paleothea.com homepage

- Tomkinson, John L., Haunted Greece: Nymphs, Vampires and other Exotika, Anagnosis, Athens, 2004, ISBN 960-88087-0-7

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)