Saturated fat: Difference between revisions

m robot Adding: es, ko, nl Modifying: ar |

Whatdidyoudo (talk | contribs) →Cardiovascular diseases: Added 10 studies and 3 review papers supporting the claim that saturated fat is not associated with heart attack risk or CHD. |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

===Cardiovascular diseases=== |

===Cardiovascular diseases=== |

||

The vast majority of observational studies have found no connection between saturated fat consumption and heart attack risk.<ref> {{cite journal|title=A Longitudinal Study of Coronary Heart Disease|journal=Circulation|date=1963|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=|id= |url=http://www.circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/28/1/20|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Diet and heart: a postscript.|journal=Br Med J.|date=1977|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=|id= |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1632514/|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Dietary intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in Japanese men living in Hawaii|journal=American Journal of Clinical Nutrition|date=1978|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=31|issue=|pages=1270-1279|id= |url=http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/abstract/31/7/1270|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Relationship of dietary intake to subsequent coronary heart disease incidence: The Puerto Rico Heart Health Program|journal=American Journal of Clinical Nutrition|date=1980|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=33|issue=|pages=1818-1827|id= |url=http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/abstract/33/8/1818|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Diet, serum cholesterol, and death from coronary heart disease. The Western Electric study|journal=The New England Journal of Medicine|date=1981|first=|last=Shekelle|coauthors=|volume=304|issue=|pages=65-70|id= |url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/304/2/65|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Diet and 20-y mortality in two rural population groups of middle-aged men in Italy|journal=American Journal of Clinical Nutrition|date=1989|first=|last=Farchi|coauthors=|volume=50|issue=|pages=1095-1103|id= |url=http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/abstract/50/5/1095|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Diet and incident ischaemic heart disease: the Caerphilly Study|journal=British Journal of Nutrition|date=1993|first=|last=Fehily|coauthors=|volume=69|issue=|pages=303-314|id= |url=http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=872408|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men: cohort follow up study in the United States |journal=British Medical Journal|date=1996|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=313|issue=|pages=84-90|id= |url=http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/313/7049/84?view=long&pmid=8688759|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Dietary Fat Intake and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|date=1997|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=337|issue=|pages=1491-1499|id= |url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/337/21/1491|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=Dietary fat intake and early mortality patterns – data from The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study|journal=Journal of Internal Medicine|date=2005|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=258|issue=2|pages=153-165|id= |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118738758/HTMLSTART|format=|accessdate= }}</ref> Three review papers, one of them including 21 cohort studies, concluded that there is no significant association between coronary heart disease and saturated fat consumption.<ref> {{cite journal|title=Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease|journal=American Journal of Clinical Nutrition|date=2010|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=|id= {{doi|10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725}}|url=http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/abstract/ajcn.2009.27725v1|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=The questionable role of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in cardiovascular disease.|journal=Journal of clinical epidemiology|date=1998|first=|last=Ravnskov|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=|id=PMID 9635993 |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9635993|format=|accessdate= }}</ref><ref> {{cite journal|title=A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease.|journal=Archives of internal medicine|date=2009|first=|last=|coauthors=|volume=|issue=|pages=|id=PMID 19364995 |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19364995|format=|accessdate= }}</ref> |

|||

[[Diet (nutrition)|Diet]]s high in saturated fat have been [[correlated]] with an increased incidence of [[atherosclerosis]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Atherosclerosis/atherosclerosis_risk.html|title=Risk factors for atherosclerosis|publisher=National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute |accessdate=8 March 2010}}</ref> and [[coronary heart disease]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/hdw/hdw_whoisatrisk.html|title=Risk factors for coronary heart disease in women|publisher=National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute|accessdate=8 March 2010}}</ref>. |

|||

Combined cholesterol and saturated fat feeding has shown an increase in cholesterol levels of [[African green monkeys]]<ref>MS Wolfe, JK Sawyer, TM Morgan, BC Bullock and LL Rudel [http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/14/4/587 Dietary polyunsaturated fat decreases coronary artery atherosclerosis in a pediatric-aged population of African green monkeys] ''Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis'' Vol 14, 587–597</ref>, while one study with baboons showed the opposite effect on LDL cholesterol.<ref>{{pmid|7625361}}</ref> |

Combined cholesterol and saturated fat feeding has shown an increase in cholesterol levels of [[African green monkeys]]<ref>MS Wolfe, JK Sawyer, TM Morgan, BC Bullock and LL Rudel [http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/14/4/587 Dietary polyunsaturated fat decreases coronary artery atherosclerosis in a pediatric-aged population of African green monkeys] ''Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis'' Vol 14, 587–597</ref>, while one study with baboons showed the opposite effect on LDL cholesterol.<ref>{{pmid|7625361}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:59, 18 March 2010

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

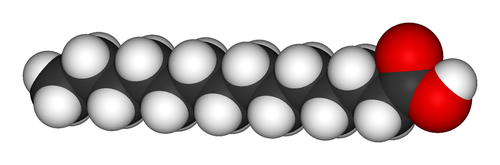

Saturated fat is fat that consists of triglycerides containing only saturated fatty acid radicals. There are several kinds of naturally occurring saturated fatty acids, which differ by the number of carbon atoms, ranging from 3 carbons (propionic acid) to 36 (Hexatriacontanoic acid). Saturated fatty acids have no double bonds between the carbon atoms of the fatty acid chain and are thus fully saturated with hydrogen atoms.

Fat that occurs naturally in tissue contains varying proportions of saturated and unsaturated fat. Examples of foods containing a high proportion of saturated fat include dairy products (especially cream and cheese but also butter and ghee); animal fats such as suet, tallow, lard and fatty meat; coconut oil, cottonseed oil, palm kernel oil, chocolate, and some prepared foods[1].

Serum saturated fatty acid is generally higher in smokers, alcohol drinkers and obese people.[2]

Fat profiles

While nutrition labels usually combine them, the saturated fatty acids appear in different proportions among food groups. Lauric and myristic acid radicals are most commonly found in "tropical" oils (e.g. palm kernel, coconut) and dairy products. The saturated fat in meat, eggs, chocolate, and nuts is primarily the triglycerides of palmitic and stearic acid.

| Food | Lauric acid | Myristic acid | Palmitic acid | Stearic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 47% | 18% | 9% | 3% |

| Butter | 3% | 11% | 29% | 13% |

| Ground beef | 0% | 4% | 26% | 15% |

| Dark chocolate | 0% | 0% | 34% | 43% |

| Salmon | 0% | 1% | 29% | 3% |

| Eggs | 0% | 0% | 27% | 10% |

| Cashews | 2% | 1% | 10% | 7% |

| Soybean oil | 0% | 0% | 11% | 4% |

Examples of saturated fatty acids

Some common examples of fatty acids:

- Butyric acid with 4 carbon atoms (contained in butter)

- Lauric acid with 12 carbon atoms (contained in coconut oil, palm oil, and breast milk)

- Myristic acid with 14 carbon atoms (contained in cow's milk and dairy products)

- Palmitic acid with 16 carbon atoms (contained in palm oil and meat)

- Stearic acid with 18 carbon atoms (also contained in meat and cocoa butter)

Stable deepfry and baking medium

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Polyunsaturated fat. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2009. |

Deepfry oils and baking fats that are high in saturated fats, like palm oil, tallow or lard, can withstand extreme heat (of 180-200 degrees Celsius) and are resistant to oxidation. A 2001 parallel review of 20-year dietary fat studies in the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Spain[15] concluded that polyunsaturated oils like soya, canola, sunflower and corn degrade easily to toxic compounds and trans fat when heated up. Prolonged consumption of trans fat-laden oxidized oils can lead to atherosclerosis, inflammatory joint disease and development of birth defects. The scientists also questioned global health authorities’ wilful recommendation of large amounts of polyunsaturated fats into the human diet without accompanying measures to ensure the protection of these fatty acids against heat- and oxidative-degradation.

Association with diseases

Cardiovascular diseases

The vast majority of observational studies have found no connection between saturated fat consumption and heart attack risk.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] Three review papers, one of them including 21 cohort studies, concluded that there is no significant association between coronary heart disease and saturated fat consumption.[26][27][28]

Combined cholesterol and saturated fat feeding has shown an increase in cholesterol levels of African green monkeys[29], while one study with baboons showed the opposite effect on LDL cholesterol.[30]

An increase in cholesterol levels has been observed in humans with an increase in saturated fat intake, such as a study of 22 hypercholesterolemic men.[31][32][33] Some studies have suggested that diets high in saturated fat increase the risk of heart disease and stroke. Epidemiological studies have found that those whose diets are high in saturated fats, including lauric, myristic, palmitic, and stearic acid, had a higher prevalence of coronary heart disease.[34][35][36][37] Additionally, controlled experimental studies have found that people consuming high saturated fat diets experience negative cholesterol profile changes.[38][39][40][41] In 2010 a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies found no statistically significant relationship between cardiovascular disease and dietary saturated fat.[42] However, the authors noted that randomized controlled clinical trials in which saturated fat was replaced with polyunsaturated fat observed a reduction in heart disease, and that the ratio between polyunsaturated fat and saturated fat may be a key factor.[42]

In 1999, volunteers were randomly assigned to either Mediterranean (which replaces saturated fat with mono and polyunsaturated fat) or a control diet showed that subjects assigned to a Mediterranean diet exhibited a significantly decreased likelihood of suffering a second heart attack, cardiac death, heart failure or stroke.[43][44]

An evaluation of data from Harvard Nurses' Health Study found that "diets lower in carbohydrate and higher in protein and fat are not associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease in women. When vegetable sources of fat and protein are chosen, these diets may moderately reduce the risk of coronary heart disease." [45]

Mayo Clinic highlighted oils that are high in saturated fats include coconut, palm oil and palm kernel oil. Those of lower amounts of saturated fats, and higher levels of unsaturated (preferably monounsaturated) fats like olive oil, peanut oil, canola oil, avocados, safflower, corn, sunflower, soy and cottonseed oils are generally healthier.[46] The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute,[47] and other health authorities like World Heart Federation[48] have urged saturated fats be replaced with polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats. The health body list olive and canola oils as sources of monosaturated oils while soybean and sunflower oils are rich with polyunsaturated fat. A 2005 research in Costa Rica suggests consumption of non-hydrogenated unsaturated oils like soybean and sunflower over palm oil.[49]

The Cochrane Collaboration published a meta-analyses of fat modification trials finding no significant effect on total mortality, but with significant reductions in the rate of cardiovascular events that was statistically significant in the high risk group.[50]

Fatty acid specificity

Epidemiological studies of heart disease have implicated the four major saturated fatty acids to varying degrees. The World Health Organization has determined that there is "convincing" evidence that myristic and palmitic acid intake increases the probability, "possible" risk from lauric acid, and no increased risk at all from stearic acid consumption.[51]

In 2005, Dutch scientists at Department of Human Biology, Maastricht University compared the effects of stearic acid with oleic and linoleic acids. Forty five subjects (27 women and 18 men) consumed, in random order, three experimental diets, each for five weeks. The results suggest stearic acid is not highly thrombogenic compared with oleic and linoleic acids.[52]

Cancer

Breast cancer

There is one theorized association between saturated fatty acids intake and increased breast cancer risk.

Prostate cancer

Myristic and palmitic saturated fatty acids are associated with prostate cancer.

Small intestine cancer

A prospective study of data from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study correlated saturated fat intake with cancer of the small intestine.[53]

Dietary recommendations

A 2004 statement released by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that "Americans need to continue working to reduce saturated fat intake..." [54] Additionally, reviews by the American Heart Association led the Association to recommend reducing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of total calories according to its 2006 recommendations.[55][56] This concurs with similar conclusions made by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Department of Health and Human Services, both of which determined that reduction in saturated fat consumption would positively affect health and reduce the prevalence of heart disease.[57][58][59]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has concluded that saturated fats negatively affect cholesterol profiles, predisposing individuals to heart disease, and recommends avoiding saturated fats in order to reduce the risk of a cardiovascular disease.[60][61]

Dr German and Dr Dillard of University of California and Nestle Research Center in Switzerland, in their 2004 review, pointed out that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified". No randomized clinical trials of low-fat diets or low-saturated fat diets of sufficient duration have been carried out. The influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.[62]

Contrary Research

The relevance of particular information in (or previously in) this article or section is disputed. (March 2008) |

One confounding issue in studies may be the formation of exogenous (outside the body) advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) and oxidation products generated during cooking, which it appears some of the studies have not controlled for. It has been suggested that, "given the prominence of this type of food in the human diet, the deleterious effects of high-(saturated)fat foods may be in part due to the high content in glycotoxins, above and beyond those due to oxidized fatty acid derivatives." The glycotoxins, as he called them, are more commonly called AGEs[63]

- A 3-year study conducted of 235 postmenopausal women with established coronary artery disease, many also having metabolic syndrome concluded that "in postmenopausal women with relatively low total fat intake, a greater saturated fat intake is associated with less progression of coronary atherosclerosis." Nevertheless, the authors deemed that "the findings do not establish causality." [64][65]

- A 2010 meta-analysis in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition looked at 21 unique studies containing over 350,000 people. They found no association between saturated fat and an increased risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, or cardiovascular disease. [66]

- A study of 297 Portuguese males with acute myocardial infarction (MI), found that "total fat intake, lauric acid, palmitic acid [two common saturated fats] and oleic acid [a monoinsaturated fat] were inversely associated with acute MI" and concluded that "low intake of total fat and lauric acid from dairy products was related to acute MI". The authors suggest that "recommendations on fatty acid intake should aim for both an upper and lower limit"[67].

- Fulani of northern Nigeria get around 25% of energy from saturated fat, yet their lipid profile is indicative of a low risk of cardiovascular disease. This finding is likely due to their high activity level and their low total energy intake.[68]

- A 2004 article in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition raised the possibility that the supposed causal relationship between saturated fats and heart disease may actually be a statistical bias. The authors take the example of the "Finnish mental hospital study" in which saturated fat intakes were monitored more closely than were total fat intakes, therefore ignoring the possibility that simply a larger fat intake may lead to a higher risk of coronary diseases. It also suggests that other parameters were overlooked, such as carbohydrates intakes.[69]

Molecular description

See also

References

- ^ Saturated fat food sources

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7661118, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7661118instead. - ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2007. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page

- ^ "Thrive Culinary Algae Oil". Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Anderson D. "Fatty acid composition of fats and oils" (PDF). Colorado Springs: University of Colorado, Department of Chemistry. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ "NDL/FNIC Food Composition Database Home Page". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "Basic Report: 04042, Oil, peanut, salad or cooking". USDA. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Oil, vegetable safflower, oleic". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ "Oil, vegetable safflower, linoleic". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ "Oil, vegetable, sunflower". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ USDA Basic Report Cream, fluid, heavy whipping

- ^ "Nutrition And Health". The Goose Fat Information Service.

- ^ "Egg, yolk, raw, fresh". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ^ "09038, Avocados, raw, California". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Grootveld, MARTIN; Silwood; Addis; Claxson; Serra; Viana (2001). "HEALTH EFFECTS OF OXIDIZED HEATED OILS1". Foodservice Research International. 13: 41. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4506.2001.tb00028.x.

- ^ "A Longitudinal Study of Coronary Heart Disease". Circulation. 1963.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Diet and heart: a postscript". Br Med J. 1977.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dietary intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in Japanese men living in Hawaii". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 31: 1270–1279. 1978.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Relationship of dietary intake to subsequent coronary heart disease incidence: The Puerto Rico Heart Health Program". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 33: 1818–1827. 1980.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Shekelle (1981). "Diet, serum cholesterol, and death from coronary heart disease. The Western Electric study". The New England Journal of Medicine. 304: 65–70.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Farchi (1989). "Diet and 20-y mortality in two rural population groups of middle-aged men in Italy". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 50: 1095–1103.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fehily (1993). "Diet and incident ischaemic heart disease: the Caerphilly Study". British Journal of Nutrition. 69: 303–314.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men: cohort follow up study in the United States". British Medical Journal. 313: 84–90. 1996.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dietary Fat Intake and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women". New England Journal of Medicine. 337: 1491–1499. 1997.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dietary fat intake and early mortality patterns – data from The Malmö Diet and Cancer Study". Journal of Internal Medicine. 258 (2): 153–165. 2005.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ravnskov (1998). "The questionable role of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in cardiovascular disease". Journal of clinical epidemiology. PMID 9635993.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease". Archives of internal medicine. 2009. PMID 19364995.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ MS Wolfe, JK Sawyer, TM Morgan, BC Bullock and LL Rudel Dietary polyunsaturated fat decreases coronary artery atherosclerosis in a pediatric-aged population of African green monkeys Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis Vol 14, 587–597

- ^ PMID 7625361

- ^ Francisco Fuentes; José López-Miranda; Elias Sánchez; Francisco Sánchez; José Paez; Elier Paz-Rojas; Carmen Marín; Purificación Gómez; José Jimenez-Perepérez; José M. Ordovás,; and Francisco Pérez-Jiménez Mediterranean and Low-Fat Diets Improve Endothelial Function in Hypercholesterolemic Men Annals of Internal Medicine 19 June 2001, Volume 134, Issue 12, pp. 1115–1119

- ^ Rivellese AA, Maffettone A, Vessby B; et al. (2003). "Effects of dietary saturated, monounsaturated and n-3 fatty acids on fasting lipoproteins, LDL size and post-prandial lipid metabolism in healthy subjects". Atherosclerosis. 167 (1): 149–58. doi:10.1016/S0021-9150(02)00424-0. PMID 12618280.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE; et al. (1997). "Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women". N. Engl. J. Med. 337 (21): 1491–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711203372102. PMID 9366580.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kromhout D, Menotti A, Bloemberg B; et al. (1995). "Dietary saturated and trans fatty acids and cholesterol and 25-year mortality from coronary heart disease: the Seven Countries Study". Prev Med. 24 (3): 308–15. PMID 7644455.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE; et al. (1999). "Dietary saturated fats and their food sources in relation to the risk of coronary heart disease in women". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 70 (6): 1001–8. PMID 10584044.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coronary heart disease in seven countries

- ^ Beegom R, Singh RB (1997). "Association of higher saturated fat intake with higher risk of hypertension in an urban population of Trivandrum in south India". Int. J. Cardiol. 58 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1016/S0167-5273(96)02842-2. PMID 9021429.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lapinleimu H, Viikari J, Jokinen E; et al. (1995). "Prospective randomised trial in 1062 infants of diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol". Lancet. 345 (8948): 471–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90580-4. PMID 7861873.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hanne Müller, Anja S. Lindman, Anne Lise Brantsæter, and Jan I. Pedersen The Serum LDL/HDL Cholesterol Ratio Is Influenced More Favorably by Exchanging Saturated with Unsaturated Fat Than by Reducing Saturated Fat in the Diet of Women The American Society for Nutritional Sciences J. Nutr 133:78–83, January 2003

- ^ Mendis S, Samarajeewa U, Thattil RO (2001). "Coconut fat and serum lipoproteins: effects of partial replacement with unsaturated fats". Br. J. Nutr. 85 (5): 583–9. doi:10.1079/BJN2001331. PMID 11348573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbey M, Noakes M, Belling GB, Nestel PJ (1994). "Partial replacement of saturated fatty acids with almonds or walnuts lowers total plasma cholesterol and low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 59 (5): 995–9. PMID 8172107.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM (2010). "Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91 (3): 535–46. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725. PMID 20071648.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N (1999). "Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study". Circulation. 99 (6): 779–85. PMID 9989963.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.aims.ubc.ca/home/modules/conference/2005/med_diet_study_1994.pdf

- ^ Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S; et al. (2006). "Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (19): 1991–2002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055317. PMID 17093250.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dietary fats: Know which types to choose Mayo Clinic website

- ^ Choose foods low in saturated fat National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), NIH Publication No. 97-4064. 1997.

- ^ Diet & cardiovascular desease World Heart Federation website

- ^ Kabagambe, Baylin, Ascherio & Campos (2005). "The Type of Oil Used for Cooking Is Associated with the Risk of Nonfatal Acute Myocardial Infarction in Costa Rica" (135 ed.). Journal of Nutrition. pp. 2674–2679.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD002137/frame.html]

- ^ World Health Organization Disease-specific recommendations

- ^ Thijssen, Myriam A.M.A.; Hornstra, Gerard; Mensink, Ronald P. (2005). "Stearic, Oleic, and Linoleic Acids Have Comparable Effects on Markers of Thrombotic Tendency in Healthy Human Subjects". Journal of Nutrition. 135 (12): 2805. PMID 16317124.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19010900, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19010900instead. - ^ Trends in Intake of Energy, Protein, Carbohydrate, Fat, and Saturated Fat — United States, 1971–2000

- ^ Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M; et al. (2006). "Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee". Circulation. 114 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. PMID 16785338.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA; et al. (2004). "Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum" (PDF). Circulation. 109 (25): 3112–21. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. PMID 15226228.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005

- ^ World Health Organization Risk factor: lipids

- ^ World Health Organization Prevention: personal choices and actions

- ^ Saturated fats: what dietary intake? J Bruce German and Cora J Dillard, Am J Clin Nutr, 2004; 80:550–9

- ^ Koschinsky T, He CJ, Mitsuhashi T; et al. (1997). "Orally absorbed reactive glycation products (glycotoxins): an environmental risk factor in diabetic nephropathy". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (12): 6474–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.12.6474. PMC 21074. PMID 9177242.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 'Surprising' data: saturated fat may slow atherosclerotic progression in postmenopausal women, OB/GYN News, July 2004

- ^ Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB, Herrington DM (2004). "Dietary fats, carbohydrate, and progression of coronary atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80 (5): 1175–84. PMC 1270002. PMID 15531663.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease1

- ^ Lopes, Carla; Aro, Antti; Azevedo, Ana; Ramos, Elisabete; Barros, Henrique (2007). "Intake and adipose tissue composition of fatty acids and risk of myocardial infarction in a male portuguese community sample". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (2). New-York: Elsevier: 276–286.

- ^ Glew RH, Williams M, Conn CA; et al. (2001). "Cardiovascular disease risk factors and diet of Fulani pastoralists of northern Nigeria". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 74 (6pages=730–6). PMID 11722953.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saturated fat prevents coronary artery disease? An American paradox