Slow loris: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 418548186 by 71.232.157.47 (talk) how true |

→Taxonomy and phylogeny: add page numbers |

||

| (104 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

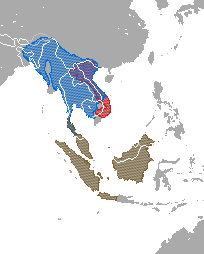

'''Slow lorises''' (genus ''Nycticebus'') are [[strepsirrhine]] [[primate]]s found in [[South Asia|South]] and [[Southeast Asia]]. They range from [[Northeast India]] to the southern [[Philippines]] and from the [[Yunnan]] province in China in the north to the island of [[Java]] in the south. There are currently five [[species]] recognized: [[Sunda slow loris]] (''N. coucang''), [[Bengal slow loris]] (''N. bengalensis''), [[pygmy slow loris]] (''N. pygmaeus''), [[Javan slow loris]] (''N. javanicus''), and the [[Bornean slow loris]] (''N. menagensis''). Slow lorises are most closely related to other [[Lorisidae|lorisids]], such as [[slender loris]]es, [[potto]]s, the [[false potto]], and [[angwantibo]]s. They are also closely related to the remaining [[Lorisiformes|lorisiforms]]—the various types of [[galago]]—as well as the [[lemur]]s of [[Madagascar]]. Their evolutionary history is unclear since their [[fossil record]] is patchy and [[molecular clock]] studies have given unclear or contradictory results. |

|||

The '''slow loris''' is any one of five species of [[loris]] classified in the genus '''''Nycticebus''''': [[Sunda Loris|Sunda Slow Loris]] (''Nycticebus coucang''), [[Bengal Slow Loris]] (''Nycticebus bengalensis''), [[Pygmy Slow Loris]] (''Nycticebus pygmaeus''), [[Javan Slow Loris]] (''Nycticebus javanicus''), and the [[Bornean Slow Loris]] (''Nycticebus menagensis''). These slow-moving [[Strepsirhini|strepsirhine]] [[primate]]s range from [[Borneo]] and the southern [[Philippines]] in [[Southeast Asia]], through [[Bangladesh]], [[Vietnam]], [[Indonesia]], [[India]] (North Eastern India, Bengal), southern [[China]] ([[Yunnan]] area), Sri Lanka and [[Thailand]]. They are hunted for their large eyes, which are prized for local [[traditional medicine]].<ref name=2006CITES/> They are also turned into a wine said to alleviate pain, or dried and smoked.<ref name=2007Black/> The Indonesian name, ''malu malu'', can be translated as "shy one".{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=393}} The pygmy species is listed as threatened by the [[U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=A06J |title=Lesser Slow loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus) |accessdate=16 May 2009 |publisher=[[U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service]] }}</ref> The [[IUCN Red List|International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species]] classifies the Javan Slow Loris as an endangered species and all other species of slow loris as vulnerable. |

|||

Like other living ("[[Crown group|crown]]") strepsirrhines, these [[Nocturnality|nocturnal]] primates have a reflective layer in their eye called a [[tapetum lucidum]], which enhances their night vision. They also have a [[rhinarium]] or "wet nose", which is a touch-based [[Sensory system|sense organ]]. Because of their close relation to lemurs and other lorisiforms, they also possess a [[toothcomb]], which is used in [[Personal grooming|personal]] and [[social grooming]]. Like nearly all [[prosimian]] ("pre-monkey") primates, they have a [[toilet-claw]], which is also used in grooming. Slow lorises have a round head, narrow snout, large eyes, and distinctive coloration patterns. Their arms and legs are nearly equal in length, and their [[Trunk (anatomy)|trunk]] is long, allowing them to twist and extend to nearby branches. The hands and feet of slow lorises have several adaptations that give them a pincer-like grip and enable them to grip branches for very long periods of time. |

|||

Slow lorises and possibly some of their closest relatives have a toxic bite—a rare trait among mammals. The toxin is produced by licking a gland on their arm, and the [[secretion]] mixes with its [[saliva]] to form the [[toxin]]. The toxin is also applied as a form of protection for their infants during grooming. Little is known about their social structure, but they are known to communicate by [[Territory (animal)|scent-marking]]. Males are highly territorial. Slow lorises reproduce slowly, and the infants are initially parked on branches or carried by either parent. They are [[omnivore]]s, eating small animals, fruit, [[Gum (botany)|tree gum]], and other vegetation. |

|||

All slow loris species are listed as either "[[Vulnerable species|Vulnerable]]" or "[[Endangered species|Endangered]]" on the [[IUCN Red List|International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species]] (IUCN Red List) and are threatened by the [[wildlife trade]] and [[habitat loss]]. Although their habit is rapidly disappearing and becoming [[Habitat fragmentation|fragmented]], making it nearly impossible for slow lorises to [[Biological dispersal|disperse]] between forest fragments, unsustainable demand from the [[exotic pet]] trade and [[traditional medicine]] has been the greatest cause for their decline. Despite local laws prohibiting the trade in slow lorises and slow loris products, as well as protection from international commercial trade under [[CITES#Appendix I|Appendix I]], slow lorises are openly sold in animal markets in Southeast Asia and smuggled to countries like Japan, where they are popularized as pets in videos posted on [[YouTube]]. Slow lorises have their teeth cut or pulled out for the pet trade, and often die from infection, blood loss, poor handling, or poor nutrition. |

|||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

The genus ''Nycticebus'', was named in 1812 by [[Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire]]{{Sfn|Groves|2005|pp=122–123}} for its [[Nocturnality|nocturnal]] behavior. The name derives from the Ancient Greek ''nycti-'' (νύξ, genitive form νυκτός), meaning "night" and ''cebus'' ({{polytonic|κῆβος}}) meaning "monkey".{{Sfn|Palmer|1904|p=465}} |

The genus ''Nycticebus'', was named in 1812 by [[Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire]]{{Sfn|Groves|2005|pp=122–123}} for its [[Nocturnality|nocturnal]] behavior. The name derives from the [[Ancient Greek]] ''nycti-'' (νύξ, genitive form νυκτός), meaning "night" and ''cebus'' ({{polytonic|κῆβος}}) meaning "monkey".{{Sfn|Palmer|1904|p=465}} |

||

The word "loris" was first used in 1765 by the French [[Natural history|naturalist]] [[Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon]] as a close equivalent to the Dutch name, ''loeris''. This [[etymology]] was later supported by the [[physician]] [[William Baird (physician)|William Baird]] in the 1820s, who noted that the Dutch word ''loeris'' signified "a clown."{{Sfn|Osman Hill|1953|pp=44–45}} |

|||

==Taxonomy and phylogeny== |

|||

{{Expand section|date=December 2010}} |

|||

==Evolutionary history== |

|||

Slow lorises are [[strepsirrhine]] primates, a group which includes [[lemur]]s, [[galago]]s, and lorises, and [[potto]]s. They are thought to have diverged from the other strepsirrhines in Asia, India (before it joined with Asia), or Africa.{{citation needed|date=January 2011}} |

|||

Slow lorises (genus ''Nycticebus'') are [[Strepsirrhini|strepsirrhine]] [[primate]]s and are related to other living [[Lorisiformes|lorisiforms]], such as [[slender loris]]es, [[potto]]s, [[false potto]]s, [[angwantibo]]s, and [[galago]]s, as well as the [[lemur]]s of [[Madagascar]].{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} The [[fossil record]] in both Asia and Africa is patchy, with most fossils dating back to the early [[Miocene]], approximately 20 million years ago.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=83}} The evolutionary origins of crown strepsirrhines have traditionally been unclear due to a lack of sufficient fossil evidence, and often contradictory [[molecular clock]], [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]], and [[Biogeography|biogeographic]] studies.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} However in 2003, teeth and jaw fragments dating to the Late Middle [[Eocene]] (''c.'' 40 million years ago) were found at the [[Lake Moeris|Birket Qarun Formation]] in the Egyptian [[Faiyum]] and were named ''[[Karanisia|Karanisia clarki]]''. This fossil species is the oldest specimen to posses a [[toothcomb]], a dental feature common among all living lorisiforms and lemurs, and has helped secure the evolutionary origins of the living ([[Crown group|crown]]) strepsirrhines in Africa.{{Sfn|Seiffert|Simons|Attia|2003|p=421}} One of the simplest models of lorisiform evolution suggests that they diverged first from the lemurs and then from each other in Africa, with one group of [[Lorisidae|lorisid]]s later migrating to Asia and evolving into the slender and slow lorises of today.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|pp=93–94}} Slow lorises are thought to have reached the islands of [[Sundaland]] during times of low sea level, when the [[Sunda shelf]] was exposed, creating a [[land bridge]] between the mainland and islands off the coast of Southeast Asia.{{Sfn|Groves|1971|p=52}} Molecular clock analysis suggests that slow lorises may have started [[speciation|evolving into distinct species]] about 6 million years ago.{{r|Lu2001}} |

|||

Although ''Karanisia'' has been cautiously placed with angwantibos (lorisoids from Africa, genus ''Arctocebus'') several other fossil species have been discovered in Asia that are more closely related to the slow lorises.{{Sfn|Seiffert|Simons|Attia|2003|p=423}} The fossil genus ''[[Nycticeboides]]'' dates from the late Miocene, and was found in Pakistan. Although it was comparable in size to the [[pygmy slow loris]] (''Nycticebus pygmaeus''), its teeth set it apart from living slow lorises.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=87}} In 1997, French paleontologists reported the discovery of a single tooth from a Miocene site in Thailand.{{Sfn|Mein|Ginsburg|1997|p=805}} The tooth most closely resembled living slow lorises, and based on this limited material, it was named [[? Nycticebus linglom|? ''Nycticebus linglom'']], using [[open nomenclature]] (the preceding "?") to indicate the tentative nature of the assignment.{{Sfn|Mein|Ginsburg|1997|p=806}} |

|||

Slow lorises are most closely related to the southeast Asian [[slender loris]]es and the [[Perodicticinae|pottos]] from Africa.{{citation needed|date=January 2011}} |

|||

The living slow lorises are generally considered to be most closely related to the slender lorises (genus ''Loris'') of [[India]], followed by the angwantibos, pottos, (genus ''Perodicticus''), and the [[false potto]] (genus ''Pseudopotto''), all from [[Central Africa|Central]] and [[West Africa]].{{Sfn|Seiffert|Simons|Attia|2003|p=423}} However, the relationship between the African lorises and the Asian lorises is complicated by biogeography, strong similarities in morphology (with both slender and robust body forms existing in both Africa and Asia), and significant differences in genetics.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} |

|||

===Taxonomy and phylogeny=== |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

|quote = ... it had the face of a bear, the hands of a monkey, [and] moved like a sloth ... |

|||

|source = American zoologist [[Dean Conant Worcester]], describing the Bornean Slow Loris in 1891.{{Sfn|Worcester|Bourns|1905|pp=683–684}} |

|||

|align = right |

|||

|quoted = 1 |

|||

}} |

|||

The first mention of a slow loris to appear in the scientific literature was written by Dutchman Arnout Vosmaer (1720–1799), who in 1770, described a specimen of ''Nycticebus coucang'' he had received two year earlier to which he gave the French name "le paresseuz pentadactyle du Bengale" ("the five-fingered sloth of Bengal"). The Dutch physician and naturalist [[Pieter Boddaert]] later questioned Vosmaer's decision to affiliate the animal with sloths, arguing instead that it was more closely aligned with the lorises of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Bengal.{{Sfn|Osman Hill|1952|p=45}} In 1794, Boddaert was the first to officially [[species description|describe]] a species of slow loris, under the name ''Tardigradus coucang''. Several species were described in the following years: ''Nycticebus bengalensis'' (originally ''Loris bengalensis'') by [[Bernard Germain de Lacépède]] in 1800; ''Nycticebus javanicus'' by [[Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire]] in 1812;{{Sfn|Saint-Hilaire|1812|p=164}} ''Nycticebus menagensis'' (originally ''Lemur menagensis'') by [[Richard Lydekker]] in 1893;{{Sfn|Lydekker|1893|pp=24–25}} and ''Nycticebus pygmaeus'' by [[John James Lewis Bonhote]] in 1907.<ref name=Nekaris2007/> Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire defined the genus ''Nycticebus'' in 1812, setting ''Nycticebus coucang'' (then called ''Tardigradus coucang'') as the [[type species]]. |

|||

In his influential 1952 book ''Primates: Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy'', the primatologist [[William Charles Osman Hill]] consolidated all the slow lorises in one [[species]], ''N. coucang''.{{Sfn|Osman Hill|1952|pp=156–163}} In 1971 [[Colin Groves]] recognized the [[Pygmy Slow Loris]] (''N. pygmaeus'') as a separate species,{{Sfn|Groves|1971|p=45}} and divided ''N. coucang'' into four [[subspecies]],{{Sfn|Groves|1971|pp=48–49}} while in 2001 Groves opined there were three species (''N. coucang'', ''N. pygmaeus'', and ''N. bengalensis''), and that ''N. coucang'' had three subspecies (''Nycticebus coucang'' coucang, ''N. c. menagensis'', and ''N. c. javanicus'').{{Sfn|Groves|2001|p=99}} Species differentiation was based largely on differences in morphology, such as size, fur color, and head markings.{{r|Chen_etal2006}} |

|||

{{cladogram|align=right|title= |

|||

|clade= |

|||

{{clade |

|||

|style=font-size:75%;line-height:75% |

|||

|label1= |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Nycticebus menagensis|N. menagensis]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1='''''N. bengalensis''''', ''[[Nycticebus coucang|N. coucang]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Nycticebus coucang|N. coucang]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Nycticebus coucang|N. coucang]]''* |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Nycticebus javanicus|N. javanicus]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Nycticebus pygmaeus|N. pygmaeus]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|caption=Phylogeny and relationships of ''N. coucang'' and related species based on [[mitochondrial DNA]] sequences.{{Sfn|Chen|Pan|Groves|Wang|2006|p=1196}} |

|||

}} |

|||

To help clarify species and subspecies boundaries, and to establish whether morphology-based classifications were consistent with evolutionary relationships, the [[phylogenetic]] relationships within the genus ''Nycticebus'' have been investigated by Chen and colleagues using [[Nucleic acid sequence|DNA sequences]] derived from the [[mitochondrial DNA|mitochondrial]] markers [[D-loop]] and [[cytochrome b|cytochrome ''b'']]. Previous [[molecular phylogenetics|molecular]] analyses using [[karyotype]]s,{{r|Cheng1993}} [[restriction enzyme]]s,{{r|Zhang1993}} and DNA sequences{{r|Wang1996}} were focused on understanding the relationships between species in the genus, not the phylogeny of the entire genus.{{r|Chen_etal2006}} Although the [[sample size]] was limited, Chen and colleagues' 2006 publication showed that the lineages of ''Nycticebus'' can be generally divided into ''N. pygmaeus''—which is deeply separated from the other species, and is thought to have been the first to diverge evolutionarily—and the other species. The analysis suggested that DNA sequences from some individuals of ''N. coucang'' and ''N. bengalensis'' apparently share a closer evolutionary relationship with each other than with members of their own species. The authors suggest that this result may be explained by [[Introgression|introgressive hybridization]], as the tested individuals of these two taxa originated from a region of [[Sympatric speciation|sympatry]] in southern Thailand; the precise origin of one of the ''N. coucang'' individuals was not known.{{r|Chen_etal2006}} This hypothesis was corroborated by a 2007 study that compared the variations in mitochondrial DNA sequences between ''N. bengalensis'' and ''N. coucang'', and suggested that there has been [[gene flow]] between the two species.{{r|Pan2007}} |

|||

==Distribution and diversity== |

==Distribution and diversity== |

||

Slow lorises are found in [[South Asia|South]] and [[Southeast Asia]]. Their collective range stretches from [[Northeast India]] through [[Indochina]], east to the [[Sulu Archipelago]] (the small, southern islands of the [[Philippines]]), and south to the island of [[Java]] (including the [[Borneo]], [[Sumatra]], and many small nearby islands). They are found in [[India]] ([[Assam]] province), [[China]] ([[Yunnan]] province), [[Laos]], [[Vietnam]], [[Cambodia]], [[Bangladesh]], [[Burma]], [[Thailand]], [[Malaysia]], the Philippines, and [[Indonesia]]. They have also been reported in [[Mindanao]], the eastern-most island of the Philippines, although they were likely [[introduced species|introduced]] there by humans.{{Sfn|Nowak|1999|p=57}} The Bengal slow loris has the largest distribution of all the slow lorises.<ref name=Swapna2008/> |

|||

{{Expand section|date=December 2010}} |

|||

Slow lorises are found only in South and Southeast Asia.{{citation needed|date=January 2011}} |

|||

Slow lorises range across [[Tropics|tropical]] and [[Subtropics|subtropical]] regions,<ref name=2006CITES/> are found in primary and secondary [[rainforest]]s, as well as [[bamboo]] groves, and [[mangrove]] forests.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=388}}{{Sfn|Nowak|1999|p=58}} They prefer forests with high, dense [[Canopy (biology)|canopies]],{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}}<ref name=2006CITES/> although some species have also be found in [[Disturbance (ecology)|disturbed habitats]], such as chocolate plantations and mixed-crop home gardens.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=388}} Due largely to their nocturnal behavior and the subsequent difficulties in accurately quantifying abundance, data about the population size or distribution patterns of slow lorises is limited. In general, encounter rates are low; a combined analysis of several field surveys conducted in South and Southeast Asia determined encounter rates ranging from as high as 0.74 lorises per kilometer for ''N. coucang'' to as low as 0.05 lorises per kilometer for ''N. pygmaeus''.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Nijman|2007|p=212}} |

|||

==Physical description== |

|||

[[File:Nycticebus pygmaeus 003.jpg|thumb|right|Slow lorises have large eyes for seeing at night.]] |

|||

Slow lorises have a round head and a less pointed snout than the [[slender loris]]es.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=80}} They have large eyes and good night vision. Their tails are either short or absent,{{Sfn|McGreal|2007a}} while their spine has an extra [[vertebra]], which allows them greater mobility when twisting and extending towards nearby branches.<ref name=2009Adam/> The [[intermembral index]] averages 89, meaning the front and back limbs are nearly equal in length. The second digit of the hand is short compared to the other digits, and its sturdy thumb helps to act like a clamp when digits three, four, and five grasp the opposite side of a tree branch. Both hands and feet provide a powerful grasp,{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=82}} which can be held for hours without losing sensation due to the presence of a [[Rete mirabile|retia mirabilia]] (network of capillaries), a trait shared among all members of the [[Loris|lorisine subfamily]].{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=80}} |

|||

==Description== |

|||

Slow lorises have an unusually low [[basal metabolic rate]]. This may be as little as 40% of the typical value for placental mammals of their size, comparable to that of [[sloth]]s. Since they consume a relatively high calorie diet that is available year round, it has been proposed that this slow metabolism is due primarily to the need to eliminate toxic compounds from their food. For example, slow lorises can feed on ''[[Gluta]]'' bark, which can be fatal to humans.<ref name=Wiens2007>{{cite journal | author = Wiens, F. ''et al.'' | year = 2007 | title = Fast food for slow lorises: is low metabolism related to secondary compounds in high-energy plant diet? | journal = Journal of Mammalogy | volume = 87 | issue = 4 | url=http://www.asmjournals.org/doi/full/10.1644/06-MAMM-A-007R1.1 | pages = 790–798 | doi = 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-007R1.1}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Smit.Faces of Lorises.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Coloration patterns around the eyes differ between the slender lorises (middle two) and the slow lorises (top and bottom).]] |

|||

Slow lorises have a round head{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=80}} because their [[skull]] is shorter from front to back compared to other prosimians.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=185}} Like other lorisids, its snout does not taper towards the front of the face as it does in lemurs. This makes the face less long and pointed.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=186}} Compared to the slender lorises, the snout of the slow loris is even less pointed.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=80}} A distinguishing feature of the slow loris skull is that the [[occipital bone]] is flattened and faces backward. The [[foramen magnum]] (hole through which the spinal cord enters) faces directly backward.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=186–187}} The brain of slow lorises has more folds (convolutions) than the brains of galagos.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=216}} |

|||

The ears are reduced in size,{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} sparsely covered in hair, and hidden in the fur.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} Similar to the slender lorises, the fur around and directly above the eyes is dark. Unlike the slender lorises, however, the white stripe that separates the eye rings and broadens both on the tip of the nose and on the forehead while also fading out on the forehead.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} Like other strepsirrhine primates, the nose and lip are covered by a moist skin called the [[rhinarium]] ("wet nose"), which is a sense organ.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=54}} |

|||

The eyes of slow lorises are forward-facing, which gives good depth-perception. Their eyes are large<ref name=2009Adam/> and possess a [[tapetum lucidum]], or reflective layer that improves low-light vision, but may also blur the images they see since the reflected light may interfere with the [[Ray (optics)|incoming light]].{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=457–458}} Slow lorises have [[Monochrome|monochromatic]] vision, meaning they see in shades of only one color. They lack the [[opsin]] gene that would allow them to detect short wavelength light, which includes the colors blue to green.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=464–465}} |

|||

The [[Dentition#Dental formula|dental formula]] of slow lorises is {{DentalFormula|upper=2.1.3.3|lower=2.1.3.3|total=36}}, meaning that on each side of its mouth it has two upper and lower [[incisor]]s, one upper and lower [[canine tooth]], three upper and lower [[premolar]]s, and three upper and lower [[Molar (tooth)|molars]], giving it a total of 36 permanent teeth.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=246}} Like all other crown strepsirrhines, their lower incisors and canine are procumbent (lie down and face outwards), forming a [[toothcomb]], which is used for [[Personal grooming|personal]] and [[social grooming]].{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=246}} |

|||

Slow lorises range in weight from as little as {{convert|265|g}} (Pygmy Slow Loris) to as much as {{convert|2100|g}} (Bengal Slow Loris).{{Sfn|Nekaris|Starr|Collins|2010|p=157}} Slow lorises have a stout body,{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} and their tail is greatly reduced and hidden beneath the dense fur.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}}{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} Their combined head and body length vary by species, with the smallest—the pygmy slow loris—measuring {{convert|18|to|21|cm|in|abbr=on}} and the Sunda slow loris measuring {{convert|27|to|38|cm|in|abbr=on}}.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} Their [[Trunk (anatomy)|trunk]] is longer than other prosimians{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=303}} because they have 15–16 [[thoracic vertebrae]] compared to 12–14 in other prosimians.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}} This gives them greater mobility when twisting and extending towards nearby branches.<ref name=2009Adam/> Their other [[vertebrae]] include seven [[cervical vertebrae]], six or seven [[lumbar vertebrae]], six or seven [[sacral vertebrae]], and seven to eleven [[caudal vertebrae]].{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}} |

|||

[[File:Nycticebus pygmaeus 003.jpg|thumb|right|The eyes of slow lorises are large and have a reflective layer, called a [[tapetum lucidum]], to help them see better at night.]] |

|||

Compared to galagos, which have longer legs than arms, slow lorises have arms and legs of nearly equal length.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} Their [[intermembral index]] (ratio of arm to leg length) averages 89, indicating their forelimbs are slightly shorter than their hindlimbs.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} Like the slender lorises, their arms are slightly longer than their body,{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}} however, the extremities of slow loris are more stout.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} |

|||

Slow lorises have a powerful grasp with both their hands and feet due to several specializations.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}}{{Sfn|Nowak|1999|p=58}} They can tightly grasp branches with little effort because of a special muscular arrangement in their hands and feet, where their thumb is nearly perpendicular (~180°) to the rest of the fingers and the [[hallux]] (big toe) ranges between being perpendicular to pointing slightly backwards.{{Sfn|Nowak|1999|p=58}}{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=348}}{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} They have a large [[flexor digitorum longus|flexor muscle]] of the toes that originates on the lower end of the [[thigh bone]], which helps impart a strong grasping ability to the hind limbs.<ref name=Forbes1896/> The second digit of the hand is short compared to the other digits,{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}} while on the foot, the fourth toe is the longest.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}} Their sturdy thumb helps to act like a clamp when digits three, four, and five grasp the opposite side of a tree branch.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=82}}{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} This gives their hands and feet a pincer-like appearance.{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} Their strong grip can be held for hours without losing sensation due to the presence of a [[Rete mirabile|retia mirabilia]] (network of capillaries), a trait shared among all members of the [[Loris|lorisine subfamily]].{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=80}}{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=348}}{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} Both slender and slow lorises have relatively short feet.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}} Like nearly all crown strepsirrhines, they have a [[toilet-claw]] or grooming claw on the second toe of each foot.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=94–95}}{{Sfn|Phillips|Walker|2002|p=91}} |

|||

Slow lorises have an unusually low [[basal metabolic rate]]. This may be as little as 40% of the typical value for placental mammals of their size, comparable to that of [[sloth]]s. Since they consume a relatively high-calorie diet that is available year round, it has been proposed that this slow metabolism is due primarily to the need to eliminate toxic compounds from their food. For example, slow lorises can feed on ''[[Gluta]]'' bark, which can be fatal to humans.{{Sfn|Wiens|Zitzmann|Hussein|2006}} |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

==Behavior and ecology== |

==Behavior and ecology== |

||

[[File:Captive N. bengalensis from Laos with 6-week baby.JPG|thumb|upright|left|alt=A small 6-week-old baby clings to its mothers back as she climbs vertically through the branches|Babies cling to the mother's back.]] |

|||

[[File:Nycticebus coucang 003.jpg|thumb|right|Slow lorises have a special network of capillaries in their hands and feet that allow them to cling to branches for hours without losing sensation.]] |

|||

Little is known about the social structure of slow lorises, but they generally spend most of the night foraging alone.<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/>{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} Slow lorises sleep during the day, usually alone but occasionally with other slow lorises.<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/> There is significant overlap between the home ranges of adults, and males may have larger home ranges than females.<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/>{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} In the absence of direct studies of slow lorises, Simon Bearder speculated that slow loris social behavior is similar to the potto, another slow moving nocturnal primate.{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=22}} Such a social system is distinguished by a lack of [[matriarchy]] and by factors that allow the slow loris to remain inconspicuous and minimize energy expenditure, by limiting vocal exchanges and alarm calls and by scent marking being the dominant form of communication.{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=22}} Vocalizations include an affiliative (friendly) call ''krik'', and a louder call resembling a crow's caw.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=387}} |

|||

Slow lorises can produce a [[secretion]] on their brachial [[gland]] (a gland on their arm) which when mixed with their saliva creates [[Volatility (chemistry)|volatile]], noxious [[toxin]] that is stored in the mouth. Before stashing their their offspring in a secure location, female slow lorises will lick their brachial gland, and then groom their young with their toothcomb, depositing the toxin on their fur. When threatened, slow lorises may also lick their brachial gland and bite their aggressors, delivering the toxin into the wound. Slow lorises are known to be reluctant to release their bite, which is likely to maximize the transfer of toxins. Animal dealers in Southeast Asia keep tanks of water nearby so that in case of a bite, they can submerge both their arm and the slow loris so that the animal will let go.{{Sfn|Alterman|1995|pp=422–423}} The toxin is similar to the allergen in cat [[dander]],{{Sfn|Hagey|Fry|Fitch-Snyder|2007}} and in tests, an [[African palm civet]] (''Nandinia binotata'') averted a sample.{{Sfn|Alterman|1995|pp=422–423}} Loris bites cause a painful swelling, but the toxin is mild and not fatal. The single case of human death reported in the scientific literature was believed to have resulted from [[anaphylactic shock]].{{Sfn|Wilde|1972}} Although the trait is rare among mammals, slow lorises may not be the only primates with this type of defense—the closely related pottos and slender lorises may share the trait.{{Sfn|Alterman|1995|pp=422–423}} |

|||

===Diet=== |

|||

Slow lorises are [[omnivores]], eating insects, [[arthropod]]s, small birds and reptiles, eggs, fruits, gums, nectar and other vegetation.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}}{{Sfn|Menon|2009|p=28}}<ref name=cons/> A 1984 study of the Sunda Slow Loris indicated that its diet consists of 71% fruit and gums and 29% insects and other animal prey.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}}{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=16}} A more detailed study of a different Sunda Slow Loris population in 2002 and 2003 showed very different dietary proportions. This study showed a diet consisting of 43.3% gum, 31.7% nectar, 22.5% fruit and just 2.5% [[anthropods]] and other animal prey.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} The most common dietary item was nectar from flowers of the Bertram palm (''[[Eugeissona tristis]]'').{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} The Sunda Slow Loris eats insects which other predators avoid due to their repugnant taste or smell.{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} Captive slow lorises eat a wide variety of foods including bananas and other fruits, rice, dog-food, raw horse meat, insects, lizards, freshly killed chicken, mice, young hamsters and milk formula that is made by mixing instant baby food with egg and honey.<ref name=cons/> Captive slow loris diets may be supplemented with cod-liver oil and bone meal.<ref name=cons/> |

|||

[[File:Nycticebus coucang 003.jpg|thumb|upright|right|Slow lorises have a special network of capillaries in their hands and feet that allow them to cling to branches for hours without losing sensation.]] |

|||

Preliminary results of studies on the Pygmy Slow Loris indicates that its diet consists primarily of gums and nectar (especially nectar from ''[[Saraca dives]]'' flowers, and that animal prey makes up 30%–40% of its diet.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}<ref name=primate/> However, one 2002 analysis of Pygmy Loris feces indicated that it contained 98% insect remains and just 2% plant remains.<ref name=cons>{{cite web|title=Nutrition of lorises and pottos|author=Schulze, H.|url=http://www.loris-conservation.org/database/captive_care/nutrition.html|publisher= |

|||

Studies suggest that slow lorises are [[polygynandry|polygynandrous]].{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2010|p=52}} Infants are either parked on branches while their parents find food or else are carried by one of the parents.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|p=83}} Due to their long [[gestation]]s (about six months), small litter sizes, low birth weights, long weaning times (three to six months),{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=384}} and long gaps between births, slow loris populations have one of the slowest growth rates among mammals of similar size.{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=22}} Pygmy slow lorises are likely to give birth to twins—from 50% to 100% of births, depending on the study; in contrast, this phenomenon is rare (3% occurrence) in Bengal slow lorises. Further, a seven-year study of captively-bred pygmy slow lorises revealed a skewed sex distribution, with 1.68 males born for every 1 female.<ref name=Pan2007/> |

|||

Loris and potto conservation database|accessdate=2011-01-03}}</ref> The Pygmy Slow Loris returns to the same gum feeding sites often and leaves conspicuous gouges on tree trunks when inducing the flow of exudates.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}<ref name=primate/> Captive Pygmy Slow Lorises also make characteristic gouge marks in wooden substrate.<ref name=cons/> It is not known how the [[Wiktionary:sympatry|sympatric]] Pygmy and Bengal Slow Loris partition their feeding niches.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} |

|||

===Diet=== |

|||

Slow lorises can eat while hanging upside down from a branch with both hands.{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} They spend about 20% of their nightly activities feeding.<ref name=primate/> |

|||

Slow lorises are [[omnivore]]s, eating insects, [[arthropod]]s, small birds and reptiles, eggs, fruits, [[gum (botany)|gums]], nectar and other vegetation.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}}{{Sfn|Menon|2009|p=28}}<ref name=nutrition/> A 1984 study of the Sunda Slow Loris indicated that its diet consists of 71% fruit and gums and 29% insects and other animal prey.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}}{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=16}} A more detailed study of a different Sunda slow loris population in 2002 and 2003 showed very different dietary proportions. This study showed a diet consisting of 43.3% gum, 31.7% nectar, 22.5% fruit and just 2.5% [[anthropods]] and other animal prey.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} The most common dietary item was nectar from flowers of the Bertram palm (''[[Eugeissona tristis]]'').{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} The Sunda slow loris eats insects which other predators avoid due to their repugnant taste or smell.{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} Captive slow lorises eat a wide variety of foods including bananas and other fruits, rice, dog-food, raw horse meat, insects, lizards, freshly killed chicken, mice, young hamsters and milk formula that is made by mixing instant baby food with egg and honey.<ref name=nutrition/> Captive slow loris diets may be supplemented with cod-liver oil and bone meal.<ref name=nutrition/> |

|||

Slow lorises can eat while hanging upside down from a branch with both hands.{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} They spend about 20% of their nightly activities feeding.<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/> Preliminary results of studies on the pygmy slow loris indicates that its diet consists primarily of gums and nectar (especially nectar from ''[[Saraca dives]]'' flowers), and that animal prey makes up 30%–40% of its diet.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/> However, one 2002 analysis of pygmy slow loris feces indicated that it contained 98% insect remains and just 2% plant remains.<ref name=nutrition/> The pygmy slow loris returns to the same gum feeding sites often and leaves conspicuous gouges on tree trunks when inducing the flow of exudates.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}}<ref name=PrimateInfoNet/> Slow lorises have been reported gouging for exudates from heights ranging from {{convert|1|m|abbr=on}} to as much as {{convert|12|m|abbr=on}}; the gouging process, whereby the loris repetitively bangs its toothcomb into the hard bark, may be noisy enough to be audible up to {{convert|10|m|abbr=on}} away. The marks remaining after gouging can be used by field workers to assess loris presence in an area.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Starr|Collins|Wilson|2010|p=159}} Captive pygmy slow lorises also make characteristic gouge marks in wooden substrates.<ref name=nutrition/> It is not known how the [[Wiktionary:sympatry|sympatric]] pygmy and Bengal slow loris partition their feeding niches.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2007|pp=28–33}} The plant gums, obtained typically from species in the family [[Fabaceae]] (peas), are high in [[carbohydrate]]s and [[lipid]]s, and can serve as a year-around source of food, or an emergency reserve when other preferred food items are scarce.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Starr|Collins|Wilson|2010|p=164}} Several anatomical adaptations present in slow lorises may enhance their ability to feed on exudates: a long narrow tongue to make it easier to reach gum stashed in cracks and crevices; a large [[caecum]] to help the animal digest [[polysaccharide|complex carbohydrates]]; and a short [[duodenum]].<ref name=Swapna2010/>{{Sfn|Nekaris|Starr|Collins|Wilson|2010|p=163}} |

|||

===Social systems=== |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

Little is known about the social structure of slow lorises, but they generally spend most of the night foraging alone.<ref name=primate>{{cite web|title=Slow loris ''Nycticebus''|url=http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/entry/slow_loris/taxon|publisher=National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin – Madison|accessdate=2010-12-17}}</ref>{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} Slow lorises sleep during the day, usually alone but occasionally with other slow lorises.<ref name=primate/> There is significant overlap between the home ranges of adults, and males may have larger home ranges than females.<ref name=primate/>{{Sfn|Rowe|1996|pp=16–17}} In the absence of direct studies of slow lorises, Simon Bearder speculated that slow loris social behavior is similar to the [[Potto]], another slow moving nocturnal primate.{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=22}} Such a social system is distinguished by a lack of [[matriarchy]] and by factors that allow the slow loris to remain inconspicuous and minimize energy expenditure, by limiting vocal exchanges and alarm calls and by scent marking being the dominant form of communication.{{Sfn|Bearder|1987|p=22}} |

|||

==Cultural references== |

|||

Beliefs about slow lorises and their use in traditional practices is deep-rooted and goes back at least 300 years, if not earlier based on oral traditions.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|pp=877–878}} In the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was reported that the people from the interior of the island of Borneo believed that slow lorises were the gatekeepers for the heavens and that each person had a personal slow loris waiting for them in the afterlife. More often, however, slow lorises are used in traditional medicine or to ward off evil.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}} The following passage from an early textbook about primates is indicative of the superstitions associated with slow lorises: <blockquote>Many strange powers are attributed to this animal by the natives of the countries it inhabits; there is hardly an event in life to man, woman or child, or even domestic animals, that may not be influenced for better or worse by the Slow Loris, alive or dead, or by any separate part of it, and apparently one cannot usually tell at the time, that one is under supernatural power. Thus a Malay may commit a crime he did not premeditate, and then find that an enemy had buried a particular part of a Loris under his threshold, which had, unknown to him, compelled him to act to his own disadvantage. ... [a Slow loris's] life is not a happy one, for it is continually seeing ghosts; that is why it hides its face in its hands.<ref name=Elliot1912/></blockquote> |

|||

In the [[Mondulkiri Province]] of Cambodia, hunters believe that lorises can heal their own broken bones immediately after falling from a branch in order to climb back up the tree, and that slow lorises have medicinal powers because they require more than one hit with a stick to die.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}} In the province of [[North Sumatra]], the slow loris is thought to bring good luck if it is buried under a house or a road.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}}<ref name=2009Adam/> In the same province, slow loris body parts were used to place curses on enemies.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}} In Java, it is thought that putting a piece of its skull in a water jug would make a husband more docile and submissive, just like a slow loris in the daytime. More recently, researchers have documented the belief that the consumption of loris meat was an aphrodisiac that improves "male power." The gall bladder of the Bengal slow loris has historically been used to make ink for tattoos by the village elders in [[Pursat Province|Pursat]] and [[Koh Kong Province]]s of Cambodia.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}} |

|||

===Predator avoidance=== |

|||

Slow lorises can produce a [[toxin]] which they mix with their saliva to use as protection against enemies. The toxin is similar to the allergen in cat [[dander]].{{Sfn|Hagey|Fry|Fitch-Snyder|2007}} Loris bites cause a painful swelling, but the toxin is mild and not fatal. Cases of human death have been due to [[anaphylactic shock]].{{Sfn|Wilde|1972}} |

|||

In the folklore of northern Thailand, the slow loris is considered venomous. This belief may have originated from the painful anaphylactic reactions that susceptible individuals experience when bitten by the animal.{{Sfn|Wilde|1972}} |

|||

===Reproduction=== |

|||

[[File:Captive N. bengalensis from Laos with 6-week baby.JPG|thumb|left|alt=A small 6-week-old baby clings to its mothers back as she climbs vertically through the branches|Babies cling to the mother's back.]] |

|||

Studies suggest that slow lorises are [[polygynandry|polygynandrous]].{{Sfn|Nekaris|Bearder|2010|p=52}} Infants are either parked on branches while their parents find food or else are carried by one of the parents.{{Sfn|Ankel-Simons|2007|pp=83}} |

|||

In Indonesia, slow lorises are called ''malu malu'' or "shy one" because they freeze and cover their face when spotted.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=393}} The [[Acehnese language|Acehnese]] name, ''buah angin'' ("wind monkey"), refers to their ability to "fleetingly but silently escape".{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=383}} |

|||

Due to their long [[gestation]]s, small litter sizes, low birth weights, long weaning times, and long gaps between births, slow loris populations have one of the slowest growth rates among mammals of similar size.{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=22}} |

|||

==Conservation== |

==Conservation== |

||

{{Main|Conservation of slow lorises}} |

{{Main|Conservation of slow lorises}} |

||

[[Image:Slow Loris Female.jpg|thumb|left|Slow lorises are popular in the [[exotic pet]] trade, which threatens wild populations.]] |

|||

{{Expand section|date=December 2010}} |

|||

The two greatest threats to slow lorises are [[deforestation]] and the [[wildlife trade]].{{Sfn|Fitch-Snyder|Livingstone|2008}} Slow lorises have lost a significant amount of habitat,{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=878}} with [[habitat fragmentation]] isolating small populations and obstructing [[biological dispersal]].<ref name=IUCN_N._javanicus/> However, despite the lost habitat, their decline is most closely associated with unsustainable trade, either as [[exotic pet]]s or for [[traditional medicine]].{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=878}} All species are listed either as "[[Vulnerable species|Vulnerable]]" or "[[Endangered species|Endangered]]" by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] (IUCN).<ref name=IUCN_N._javanicus/><ref name=IUCN_N._menagensis/><ref name=IUCN_N._coucang/><ref name=IUCN_N._bengalensis/><ref name=IUCN_N._pygmaeus/> When all five species were considered a single species, imprecise population data and their regular occurrence in Southeast Asian animal markets inaccurately suggested that slow lorises were common, resulting in a previous [[IUCN Red List]] assessment of "[[Least Concern]]" as recently as 2000.<ref name=IUCN_N._coucang/>{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=383}}{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=17}} Since 2007, all slow loris species are protected from commercial international trade under [[CITES#Appendix I|Appendix I]].{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=390}} Furthermore, local trade is illegal because every nation in which they occur naturally has laws protecting them.<ref name=2010NatGeoNewsWatch/> |

|||

Despite their CITES Appendix I status and local legal protection, slow lorises are still threatened by both local and international trade due to problems with enforcement.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}}{{Sfn|Nekaris|Munds|2010|p=390}} Additionally, surveys are needed to determine existing population densities and habitat viability for all species of slow loris. Connectivity between protected areas is important for slow lorises because they are not adapted to dispersing across the ground over large distances.{{Sfn|Thorn|Nijman|Smith|Nekaris|2009|p=295}} |

|||

[[Image:Slow Loris Female.jpg|thumb|right|Slow lorises, such as the Pygmy Loris (''Nycticebus pygmaeus''), are very popular in the [[exotic pet]] trade, which threatens wild populations.]] |

|||

Slow lorises are threatened by [[deforestation]], the [[exotic pet]] trade, and [[traditional medicine]].<ref name=pet>[http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/06/photogalleries/animal-pictures/ National Geographic News: Top 5 Winners, Losers of the New Animal Trade]</ref> All species are listed either as "[[Vulnerable species|Vulnerable]]" or "[[Endangered species|Endangered]]" by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] (IUCN). |

|||

Populations of slow loris species, such as the Bengal and Sunda slow loris, are not faring well in zoos. Of the 29 captive specimens in North American zoos in 2008, several are hybrids that cannot breed while most are past their reproductive years. The last captive birth for these species in North America was in 2001 in San Diego. Pygmy slow lorises are doing better in North American zoos. The population has grown to 74 animals between the time they were imported in the late 1980s and 2008, with most of them born at the [[San Diego Zoo]].{{Sfn|Fitch-Snyder|Livingstone|2008}} |

|||

The slow loris has become a popular but illegal pet, mostly in Japan, but also in the United States.<ref name=pet/> Its popularity has swelled due to popular [[YouTube]] videos showing them being tickled.<ref name=2009Adam/> |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

===Wildlife trade=== |

|||

Prior to the 1960, the hunting of slow lorises was sustainable,{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=878}} but due to growing demand, decreased supply, and the subsequent increased value of the marketed wildlife, slow lorises have been [[Overexploitation|overexploited]] and are in decline.{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=17}} With the use of modern technology, such as battery-powered search lights, slow lorises have become easier to hunt because of their [[Tapetum lucidum|eye shine]].{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=22}} Traditional medicine made from loris parts are thought to cure many diseases,{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=882}} and the demand for this medicine from wealthy urban areas has replaced the subsistence hunting traditionally performed in poor rural areas.{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=17}} A survey by primatologist Anna Nekaris ''et al''. (2010) showed that these belief systems were so strong that the majority of respondents expressed reluctance to consider alternatives to loris-based medicines.{{Sfn|Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010|p=17}} |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

|quote = Even the best breeding facilities have great difficulty breeding lorises, and those that do often have difficulty keeping them alive. It is so easy to get access to wild-caught lorises, it is highly doubtful that a seller who claims to have captive-bred ones is telling the truth. |

|||

|source = Primatologist Anna Nekaris, in 2009 discussing the misleading information posted on YouTube.<ref name=Hance2011/> |

|||

|align = left |

|||

|width = 25em |

|||

|quoted = 1 |

|||

}} |

|||

Slow lorises are sold locally at street markets, but are also sold internationally over the Internet and in pet stores.<ref name=2007Sakamoto/>{{Sfn|Navarro-Montes|Nekaris|Parish|2009}} They are especially popular or trendy in Japan, particularly among women.<ref name=2007Black/><ref name=2007Sakamoto/> The reasons for their popularity, according to the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society (JWCS), are that "they're easy to keep, they don't cry, they're small, and just very cute."<ref name=2007Black/> Because of their "cuteness", videos of pet slow lorises are some of the mostly frequently watched animal-related [[viral video]]s on [[YouTube]].<ref name=2009Adam/><ref name=Hance2011/> According to Nekaris, these videos are misunderstood by most people who watch them since most don't realize it is illegal to own them as pets and that the slow lorises in the videos are only docile because that is their defensive reaction to threatening situations.<ref name=Hance2011/> Despite frequent advertisements by pet shops in Japan, the [[World Conservation Monitoring Centre]] (WCMC) reported only a few dozen slow lorises were imported in 2006, suggesting frequent smuggling.<ref name=2006CITES/> Slow lorises are also smuggled to China, Taiwan, Europe, the United States, and Saudi Arabia for use as pets.<ref name=2007Black/>{{Sfn|Navarro-Montes|Nekaris|Parish|2009}} |

|||

[[File:Nycticebus tooth removal 01.jpg|thumb|right|alt=A small, young slow loris is gripped by its limbs while its front teeth are cut with fingernail cutter|Slow lorises have their front teeth cut or pulled before being sold as pets, a practice that often results in infection and death.]] |

|||

Even within their countries of origin, slow lorises are very popular pets,{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=883}} particularly in Indonesia.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=877}} They are seen as a "living toy" for children by local people or are bought out of pity by Western tourists or expatriates. Neither local nor foreign buyers usually know anything about these primates, their endangered status, or that the trade is illegal.{{Sfn|Sanchez|2008|p=10}} Furthermore, few know about their strong odor or their potentially lethal bite.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=884}} According to 59 monthly surveys and interviews with local traders taken during late 2000s, nearly a thousand locally sourced slow lorises exchanged hands in the Medan bird market in North Sumatra.{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=883}} |

|||

International trade usually results in a high mortality rate during transit, between 30% and 90%. Slow lorises also experience many health problems as a result of both local and international trade.<ref name=2007Black/> In order to give the impression that the primates are tame and appropriate pets for children,{{Sfn|McGreal|2008|p=8}} to protect people from their potentially toxic bite,<ref name=2010NatGeoNewsWatch/> or to deceive buyers into thinking the animal is a baby,<ref name=2007Black/> animal dealers either pull the front teeth with pliers or wire cutters or they cut them off with nail cutters.{{Sfn|Sanchez|2008|p=10}}<ref name=2009Adam/>{{Sfn|Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010|p=883}} This results in severe bleeding, which sometimes causes [[Shock (circulatory)|shock]] or death,<ref name=2009Adam/> and frequently leads to dental infection, which is fatal in 90% of all cases.{{Sfn|Sanchez|2008|p=10}}{{Sfn|McGreal|2008|p=8}} Without their teeth, the animals are no longer able to fend for themselves in the wild, and must remain in captivity for life.{{Sfn|Sanchez|2008|p=10}}{{Sfn|McGreal|2008|p=8}} The slow lorises found in animal markets are usually underweight and malnourished, and have had their fur dyed, which complicates species identification at rescue centers.{{Sfn|Navarro-Montes|Nekaris|Parish|2009}} As many as 95% of the slow lorises rescued from the markets die of dental infection or improper care.{{Sfn|McGreal|2008|p=8}} |

|||

As part of the trade, infants are pulled prematurely from their parents, leaving them unable to remove their own urine, feces, and oily skin secretions from their fur. Slow lorises have a special network of blood vessels in their hands and feet, which makes them vulnerable to cuts when pulled from the wire cages they are kept in.<ref name=2007Black/> Slow lorises are also very stress-sensitive and do not do well in captivity. Infection, stress, pneumonia, and poor nutrition lead to high death rates among pet lorises.{{Sfn|Sanchez|2008|p=10}} Common health problems seen in pet slow lorises include undernourishment, tooth decay, diabetes, obesity, and kidney failure.<ref name=Hance2011/> Pet owners also fail to provide proper care because they are usually sleeping when the nocturnal pet is awake.{{Sfn|McGreal|2008|p=8}}<ref name=Hance2011/> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= |

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= |

||

<ref name=Chen_etal2006>{{cite doi | 10.1007/s10764-006-9032-5}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Cheng1993>{{cite journal | last = Cheng | first1 = Z.P. | last2 = Zhang | first2 = Y.P. | last3 = Shi | first3 = L.M. | last4 = Liu | first4 = R.Q. | last5 = Wang | first5 = Y.X. | title = Studies on the chromosomes of genus ''Nycticebus'' | journal = Primates | year = 1993 | volume = 34 | issue = 1 | pages = 37–53 | doi = 10.1007/BF02381279}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="CITES">{{cite web | title = Appendices I, II and III | publisher = Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) | year = 2010 | url = http://www.cites.org/eng/app/Appendices-E.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> |

<ref name="CITES">{{cite web | title = Appendices I, II and III | publisher = Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) | year = 2010 | url = http://www.cites.org/eng/app/Appendices-E.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=2006CITES>{{cite conference | author = Management Authority of Cambodia | title = Notification to Parties: Consideration of Proposals for Amendment of Appendices I and II | date = 3–15 June 2007 | publisher = CITES | |

<ref name=2006CITES>{{cite conference | author = Management Authority of Cambodia | title = Notification to Parties: Consideration of Proposals for Amendment of Appendices I and II | date = 3–15 June 2007 | publisher = CITES | page = 31 | location = Netherlands | url = http://www.cites.org/eng/notif/2006/E052.pdf | format = PDF | accessdate = 8 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vacXUYZJ | archivedate = 8 January 2011}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=2009Adam>{{cite news | last = Adam | first = D. | title = The eyes may be cute but the elbows are lethal | newspaper = The Sydney Morning Herald | date = 9 July 2009 | url = http://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/the-eyes-may-be-cute-but-the-elbows-are-lethal-20090708-ddg8.html | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vb9EUVYe | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

<ref name=2009Adam>{{cite news | last = Adam | first = D. | title = The eyes may be cute but the elbows are lethal | newspaper = The Sydney Morning Herald | date = 9 July 2009 | url = http://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/the-eyes-may-be-cute-but-the-elbows-are-lethal-20090708-ddg8.html | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vb9EUVYe | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

||

| Line 90: | Line 174: | ||

<ref name=2007Black>{{cite news | last = Black | first = R. | title = Too cute for comfort | newspaper = BBC News | date = 8 June 2007 | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6731631.stm | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vcAx6E8j | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

<ref name=2007Black>{{cite news | last = Black | first = R. | title = Too cute for comfort | newspaper = BBC News | date = 8 June 2007 | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6731631.stm | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vcAx6E8j | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=IUCN_N._bengalensis>{{IUCN | id = 39758 | taxon = ''Nycticebus bengalensis'' | assessors = Streicher, U., Singh, M., Timmins, R.J. & Brockelman, W. | assessment_year = 2008 | version = 2010.4 | accessdate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

<ref name=IUCN_N._coucang>{{IUCN | id = 39759 | taxon = ''Nycticebus coucang'' | assessors = Nekaris, A. & Streicher, U. | assessment_year = 2008 | version = 2010.4 | accessdate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

===Literature cited=== |

|||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

<ref name=IUCN_N._javanicus>{{IUCN | id = 39761 | taxon = ''Nycticebus javanicus'' | assessors = Nekaris, A. & Shekelle, M. | assessment_year = 2008 | version = 2010.4 | accessdate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book | last = Ankel-Simons | first = F. | title = Primate Anatomy | edition = 3rd | publisher = Academic Press | year = 2007 |isbn = 0-12-372576-3 | ref = harv}} |

|||

<ref name=IUCN_N._menagensis>{{IUCN | id = 39760 | taxon = ''Nycticebus menagensis'' | assessors = Nekaris, A. & Streicher, U. | assessment_year = 2008 | version = 2010.4 | accessdate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Primate Societies|last1=Bearder|first1=Simon K.|chapter=Lorises, Bushbabies, and Tarsiers: Diverse Societies in Solitary Foragers|editors=Smuts, Barbara B.; Cheney, Dorothy L.; Seyfarth, Robert M.; Wrangham, Richard W. & Struhsaker, Thomas T|year=1987|publisher=The University of Chicago Press|isbn=0-226-76716-7 | ref = harv}} |

|||

<ref name=IUCN_N._pygmaeus>{{IUCN | id = 14941 | taxon = ''Nycticebus pygmaeus'' | assessors = Streicher, U., Ngoc Thanh,V., Nadler,T., Timmins, R.J. & Nekaris, A. | assessment_year = 2008 | version = 2010.4 | accessdate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* {{MSW3 Primates}} |

|||

<ref name=2010NatGeoNewsWatch>{{cite web | last = Braun | first = D. | title = Love potions threaten survival of lorises | publisher = National Geographic | year = 2010 | url = http://blogs.nationalgeographic.com/blogs/news/chiefeditor/2010/05/lorises-at-risk-from-illegal-trade.html | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vb6w7hxs | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* <!-- Hagey|Fry|Fitch-Snyder|2007 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/978-0-387-34810-0_12}} {{subscription}} |

|||

<ref name=2007Sakamoto>{{cite web | last = Sakamoto | first = Masayuki | title = Slow lorises fly so fast into Japan | year = 2007 | publisher = Japan Wildlife Conservation Society | url = http://www.jwcs.org/english/07.5.26%20Cop14%20Slow%20lorise%20report.pdf | format = PDF | accessdate = 26 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5w15o41GF | archivedate = 26 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Elliot1912>{{cite book | last1 = Elliot | first1 = Daniel Giraud | title = A Review of the Primates | volume = 1 | year = 1912 | publisher = American Museum of Natural History | location = New York, New York | pages = 30–31 | url = http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/10287437}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book|title=Mammals of India|last1=Menon|first1=Vivek|page=28|year=2009|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-14067-4}} |

|||

<ref name=Forbes1896>{{cite book | last1 = Forbes | first1 = Henry O. | title = A Hand-book to the Primates | year = 1896 | volume = 1 | location = London | publisher = E. Lloyd | page =34 | url = http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/10100678}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book | last1 = Nekaris | first1 = N.A.I. | last2 = Bearder | first2 = S.K. | chapter = Chapter 3: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness | year = 2007 | pages = 28–33 | title = Primates in Perspective | editor1-last = Campbell | editor1-first = C. | editor2-last = Fuentes | editor2-first = C.A. | editor3-last = MacKinnon | editor3-first = K. | editor4-last = P{anger | editor4-first = M. |editor5-last = Bearder | editor5-first = S. | editor5-last = Stumpf | editor5-first = R. | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = U.S.A. | isbn = 978-0195171334}} |

|||

<ref name=Hance2011>{{cite web | last = Hance | first = Jeremy | title = 'Cute' umbrella video of slow loris threatens primate | year = 2011 | publisher = mongabay.com | url = http://news.mongabay.com/2011/0313-hance_umbrella_loris.html | accessdate = 16 March 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5xElHShy2 | archivedate = 16 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book | last1 = Nekaris | first1 = N.A.I. | last2 = Bearder | first2 = S.K. | chapter = Chapter 4: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness | year=2010 | pages = 34–54 | title = Primates in Perspective | editor1-last = Campbell | editor1-first = C. | editor2-last = Fuentes | editor2-first = C.A. | editor3-last = MacKinnon | editor3-first = K. | editor4-last = Bearder | editor4-first = S. | editor5-last = Stumpf | editor5-first = R. | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = U.S.A. | isbn = 978-0195390438}} |

|||

<ref name=Lu2001>{{cite journal | last1 = Lu |first1 = X. M. | last2 = Wang | first2 = Y. X. | last3 = Zhang | last3 = Y. P. | title = Divergence and phylogeny of mitochondrial cytochrome ''b'' gene from species in genus ''Nycticebus'' | journal = Zoological Research | year = 2001 | volume= 22 | pages = 93–98 | language = Chinese | issn = 0254-5853}}</ref> |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Munds|2010 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3_22}} |

|||

<ref name=Nekaris2007>{{cite journal | last1 = Nekaris | first1 = K.A.I. | last2 = Jaffe | first2 = S. | title = Unexpected diversity of slow lorises (''Nycticebus spp.'') within the Javan pet trade: implications for slow loris taxonomy | journal = Contributions to Zoology | volume = 76 | number = 3 | year = 2007 | pages = 187–196 | url = http://www.djmt.nl/cgi/t/text/get-pdf?idno=m7603a04;c=ctz | format = PDF | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5vc6Jc13z | archivedate = 9 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* <!-- Palmer|1904 -->{{cite book | last = Palmer | first = T.S. | title = Index Generum Mammalium: A List of the Genera and Families of Mammals | year = 1904 | publisher = Washington: G.P.O. | url = http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/27792212 | oclc = 1912921 | ref = harv}} |

|||

<ref name=nutrition>{{cite web | last = Schulze | first = H. | title = Nutrition of lorises and pottos | url = http://www.loris-conservation.org/database/captive_care/nutrition.html | publisher = Loris and potto conservation database | date = 11 July 2008 | accessdate = 3 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

* {{cite book|title=The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates|last1=Rowe|first1=Noel|pages=16–17|year=1996|publisher=Pogonias Press|isbn=0-9648825-0-7}} |

|||

<ref name=Pan2007>{{cite doi|10.1007/s10764-007-9157-1}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=PrimateInfoNet>{{cite web | title = Slow loris ''Nycticebus'' | url = http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/entry/slow_loris/taxon | publisher = National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin – Madison | accessdate = 17 December 2010}}</ref> |

|||

* <!-- Wilde|1972 -->{{cite pmid | 5075669}} {{subscription}} |

|||

<ref name=Swapna2008>{{cite journal | last1 = Swapna | first1 = N. | last2 = Gupta | first2 = Atul | last3 = Radhakrishna | first3 = Sindhu | title = Distribution survey of Bengal Slow Loris ''Nycticebus bengalensis'' in Tripura, northeastern India | journal = Asian Primates Journal | year = 2008 | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 37–40 | url = http://www.primate-sg.org/PDF/APJ1.1.bengalensis.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Swapna2010>{{cite doi | 10.1002/ajp.20760}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Wang1996>{{cite journal | last1 = Wang | first1 = Wen | last2 = Su | first2 = Bing | last3 = Lan | first3 = Hong | last4 = Liu | first4 = Ruiqing | last5 = Zhu | first5 = Chunling | last6 = Nie | first6 = Wenhui | last7 =Chen | first7 = Yuze | last8 = Zhang | first8 = Yaping | title = Interspecific differentiation of the slow lorises (genus ''Nycticebus'') inferred from ribosomal DNA restriction maps | journal = Zoological Research | year = 1996 | volume = 17 | pages = 89–93}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Zhang1993>{{cite journal | last1 = Zhang | first1 = Y. P. | last2 = Cheng | first2 = Z. P. | last3 = Shi | first3 = L. M. | title = Phylogeny of the slow lorises (genus ''Nycticebus''): An approach using mitochondrial DNA restriction enzyme analysis | journal = International Journal of Primatology | year = 1993 | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 167–175 | doi = 10.1007/BF02196510}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

===Literature cited=== |

|||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

* <!-- Alterman|1995 -->{{cite book | last = Alterman | first = L. | year = 1995 | contribution = Toxins and toothcombs: potential allospecific chemical defenses in ''Nycticebus'' and ''Perodicticus'' | editor1-last = Alterman | editor1-first = L. | editor2-last = Doyle | editor2-first = G.A. | editor3-last = Izard | editor3-first = M.K | title = Creatures of the dark: the nocturnal prosimians | publisher = Plenum Press | pages = 413–424 | oclc = 33441731 | isbn = 978-0-306-45183-6 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Ankel-Simons|2007 -->{{cite book | last = Ankel-Simons | first = F. | title = Primate Anatomy | edition = 3rd | publisher = Academic Press | year = 2007 |isbn = 0-12-372576-3 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Bearder|1987 -->{{cite book | last = Bearder | first = Simon K. | title = Primate Societies | chapter = Lorises, Bushbabies, and Tarsiers: Diverse Societies in Solitary Foragers | editor1-last = Smuts | editor1-first = Barbara B. | editor2-last = Cheney | editor2-first = Dorothy L. | editor3-last = Seyfarth | editor3-first = Robert M. | editor4-last = Wrangham | editor4-first = Richard W. | editor5-last = Struhsaker | editor5-first = Thomas T | year = 1987 | publisher = The University of Chicago Press | isbn = 0-226-76716-7 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Chen|Pan|Groves|Wang|2006 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/s10764-006-9032-5}} |

|||

* <!-- Fitch-Snyder|Livingstone|2008 -->{{cite journal | last1 = Fitch-Snyder | first1 = H | last2 = Livingstone | first2 = K | title = Lorises: The Surprise Primate | journal = ZooNooz | year = 2008 | publisher = San Diego Zoo | issn = 0044-5282 | pages = 10–14 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Groves|2005 -->{{MSW3 Primates|id=12100112}} |

|||

* <!-- Groves|1971 -->{{cite book | contribution = Systematics of the genus ''Nycticebus'' | last1 = Groves | first1 = Colin P. | year = 1971 | title = Proceedings of the Third International Congress of Primatology | volume = 1 | location = Zürich, Switzerland | pages = 44–53 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Hagey|Fry|Fitch-Snyder|2007 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/978-0-387-34810-0_12}} {{subscription}} |

|||

* <!-- Lydekker|1893 -->{{cite journal | last = Lydekker | first = R. | title = Mammalia | journal = Zoological Record | year = 1893 | volume = 29 | pages = 55 pp | ref = harv |url = http://books.google.com/books?id=rrLlB6mBQOYC&pg=RA1-PA25}} |

|||

* <!-- McGreal|2008 -->{{cite journal | last = McGreal | first = S. | title = Vet Describes the Plight of Indonesia's Primates | journal = IPPL News | volume = 35 | number = 1 | year = 2008 | publisher = International Primate Protection League | issn = 1040-3027 | pages = 7–8 | url = http://www.ippl.org/newsletter/2000s/103_v35_nl_2008-05.pdf#page=7 | format = PDF | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- McGreal|2007a -->{{cite journal | last = McGreal | first = S. | title = Loris Confiscations Highlight Need for Protection | journal = IPPL News | volume = 34 | number = 1 | year = 2007a | publisher = International Primate Protection League | issn = 1040-3027 | page = 3 | url = http://www.ippl.org/newsletter/2000s/101_v34_n1_2007-04.pdf#page=3 | format = PDF | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Mein|Ginsburg|1997 -->{{fr}} {{cite journal | last1 = Mein | first1 = P. | last2 = Ginsburg | first2 = L. | year = 1997 | title = Les mammifères du gisement miocène inférieur de Li Mae Long, Thaïlande : systématique, biostratigraphie et paléoenvironnement | journal = Geodiversitas | volume = 19 | issue = 4 | pages = 783–844 | issn = 1280-9659 | ref = harv}} [http://www.webcitation.org/5vwR2fDm8 Abstract in French and English]. |

|||

* <!-- Menon|2009 -->{{cite book | title = Mammals of India | last = Menon | first = Vivek | year = 2009 | publisher = Princeton University Press | isbn = 978-0-691-14067-4 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Navarro-Montes|Nekaris|Parish|2009 -->{{cite journal | last1 = Navarro-Montes | first1 = Angelina | last2 = Nekaris | first2 = Anna | last3 = Parish | first3 = Tricia J. | title = Trade in Asian slow lorises (''Nycticebus''): using education workshops to counter an increase in illegal trade | journal = Living Forests | year = 2009 | issue = 15 | url = http://www.kfbglivingforests.org/content/issue15/feature1.php | accessdate = 26 January 2011 | archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5w1Asy2fc | archivedate = 26 January 2011 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Bearder|2010 -->{{cite book | last1 = Nekaris | first1 = N.A.I. | last2 = Bearder | first2 = S.K. | chapter = Chapter 4: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness | year = 2010 | pages = 34–54 | title = Primates in Perspective | editor1-last = Campbell | editor1-first = C. | editor2-last = Fuentes | editor2-first = C.A. | editor3-last = MacKinnon | editor3-first = K. | editor4-last = Bearder | editor4-first = S. | editor5-last = Stumpf | editor5-first = R. | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = U.S.A. | isbn = 978-0-195-39043-8 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Munds|2010 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3_22}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Shepherd|Starr|Nijman|2010 -->{{cite doi | 10.1002/ajp.20842}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Starr|Collins|2010 -->{{cite doi | 10.1007/978-1-4419-6661-2_8}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Bearder|2007 -->{{cite book | last1 = Nekaris | first1 = N.A.I. | last2 = Bearder | first2 = S.K. | chapter = Chapter 3: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness | year = 2007 | pages = 28–33 | title = Primates in Perspective | editor1-last = Campbell | editor1-first = C. | editor2-last = Fuentes | editor2-first = C.A. | editor3-last = MacKinnon | editor3-first = K. | editor4-last = P{anger | editor4-first = M. |editor5-last = Bearder | editor5-first = S. | editor5-last = Stumpf | editor5-first = R. | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = U.S.A. | isbn = 978-0-195-17133-4 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Nekaris|Nijman|2007 -->{{cite doi | 10.1159/000102316}} |

|||

* <!-- Nowak|1999 -->{{cite book | last = Nowak | first = R.M. | year = 1999 | publisher = Johns Hopkins University Press | title = Walker's Mammals of the World | edition = 6th | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=unODoWa7CM4C&printsec=frontcover | isbn = 0-8018-5789-9 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Osman Hill|1952 -->{{cite book | last = Osman Hill | first = W. C. | authorlink = William Charles Osman Hill | title = Primates: Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy. Strepsirhini | year = 1952 | location = Edinburgh, Scotland | publisher = Edinburgh University Press | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Osman Hill|1953 -->{{cite doi | 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1953.tb00153.x}} |

|||

* <!-- Palmer|1904 -->{{cite book | last = Palmer | first = T.S. | title = Index Generum Mammalium: A List of the Genera and Families of Mammals | year = 1904 | publisher = Washington: G.P.O. | url = http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/27792212 | oclc = 1912921 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Phillips|Walker|2002 -->{{cite book | last1 = Phillips | first1 = E.M. | last2 = Walker | first2 = A. | year = 2002 | chapter = Chapter 6: Fossil lorisoids | editor1-last = Hartwig | editor1-first = W.C. | title = The primate fossil record | publisher = Cambridge University Press | isbn = 978-0-521-66315-1 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Rowe|1996 -->{{cite book | last = Rowe | first = Noel | title = The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates | year = 1996 | publisher = Pogonias Press | isbn = 0-9648825-0-7 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Sanchez|2008 -->{{cite journal | last = Sanchez | first = K.L. | title = Indonesia's Slow Lorises Suffer in Trade | journal = IPPL News | volume = 35 | number = 2 | year = 2008 | publisher = International Primate Protection League | issn = 1040-3027 | page = 10 | url = http://www.ippl.org/newsletter/2000s/105_v35_n2_2008-09.pdf#page=10 | format = PDF | accessdate = 9 January 2011 | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Seiffert|Simons|Attia|2003 -->{{cite doi | 10.1038/nature01489}} |

|||

* <!-- Saint-Hilaire|1812 -->{{cite book | last1 = Saint-Hilaire | first1 = Étienne Geoffroy |journal = Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle | year = 1812 | title = Suite au Tableau des Quadrummanes. Seconde Famille. Lemuriens. Strepsirrhini | volume = 19 | page = 156–170 | url = http://www.archive.org/stream/annalesdumusum19mus#page/164/mode/2up | language = French | ref = harv}} |

|||

* <!-- Starr|Nekaris|Streicher|Leung|2010 -->{{cite doi | 10.3354/esr00285}} |

|||

* <!-- Thorn|Nijman|Smith|Nekaris|2009 -->{{cite doi | 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00535.x}} |

|||

* <!-- Wiens|Zitzmann|Hussein|2006 -->{{cite doi | 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-007R1.1}} |

|||

* <!-- Wilde|1972 -->{{cite pmid | 5075669}} |

|||

* <!-- Worcester|Bourns|1905 -->{{cite journal | last1 = Worcester | first1 = D. C. | last2 = Bourns | first2 = F. S. | year = 1905 | title = Letters from the Menage Scientific Expedition to the Philippine Islands | journal = Bulletin of the Minnesota Academy of Natural Sciences | volume = 4 | pages = 131–172 | ref = harv | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=FI0YAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA131}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

{{Refend}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wikispecies|Nycticebus|Slow loris}} |

|||

{{Commons category|Nycticebus|Slow loris}} |

|||

* [http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/entry/slow_loris Primate Fact Sheets: Slow loris (''Nycticebus'')] – Primate Info Net |

* [http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/entry/slow_loris Primate Fact Sheets: Slow loris (''Nycticebus'')] – Primate Info Net |

||

* [http://lemur.duke.edu/category/nocturnal-lemurs/slow-loris/ Slow Loris fact sheets] – Duke University, USA |

* [http://lemur.duke.edu/category/nocturnal-lemurs/slow-loris/ Slow Loris fact sheets] – Duke University, USA |

||

* [http://www.loris-conservation.org/ loris-conservation.org] – provides links to websites related to conservation of Asian lorises and African pottos |

* [http://www.loris-conservation.org/ loris-conservation.org] – provides links to websites related to conservation of Asian lorises and African pottos |

||

{{Lorisidae nav}} |

{{Lorisidae nav}} |

||

{{Subject bar | book = Slow loris | portal1 = Primates | portal2 = Asia | commons = y | commons-search = Category:Nycticebus | species = y | species-search = Nycticebus}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2010}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2010}} |

||

| Line 141: | Line 270: | ||

[[Category:Mammals of India]] |

[[Category:Mammals of India]] |

||

[[Category:Mammals of Malaysia]] |

[[Category:Mammals of Malaysia]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Mammals of Thailand]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Mammals of Cambodia]] |

||

[[Category:Mammals of Bangladesh]] |

[[Category:Mammals of Bangladesh]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Mammals of Borneo]] |

||

[[de:Plumploris]] |

[[de:Plumploris]] |

||

Revision as of 00:30, 17 March 2011

| Slow lorises[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sunda Slow Loris Nycticebus coucang | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Nycticebus E. Geoffroy, 1812

|

| Type species | |

| Tardigradus coucang Boddaert, 1785

| |

| Species | |

|

Nycticebus coucang | |

| |