Slow loris

| Slow lorises[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sunda Slow Loris Nycticebus coucang | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Nycticebus E. Geoffroy, 1812

|

| Type species | |

| Tardigradus coucang Boddaert, 1785

| |

| Species | |

|

Nycticebus coucang | |

| |

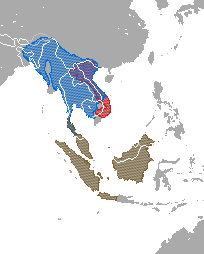

| Distribution of Nycticebus spp. red = N. pygmaeus; blue = N. bengalensis; brown = N. coucang, N. javanicus, & N. menagensis | |

The slow loris is any one of five species of loris classified in the genus Nycticebus: Sunda Slow Loris (Nycticebus coucang), Bengal Slow Loris (Nycticebus bengalensis), Pygmy Slow Loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus), Javan Slow Loris (Nycticebus javanicus), and the Bornean Slow Loris (Nycticebus menagensis). These slow-moving strepsirhine primates range from Borneo and the southern Philippines in Southeast Asia, through Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, India (North Eastern India, Bengal), southern China (Yunnan area), Sri Lanka and Thailand. They are hunted for their large eyes, which are prized for local traditional medicine.[3] They are also turned into a wine said to alleviate pain, or dried and smoked.[4] The Indonesian name, malu malu, can be translated as "shy one".[5] The pygmy species is listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[6] The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species classifies the Javan Slow Loris as an endangered species and all other species of slow loris as vulnerable.

Etymology

The genus Nycticebus, was named in 1812 by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire[1] for its nocturnal behavior. The name derives from the Ancient Greek nycti- (νύξ, genitive form νυκτός), meaning "night" and cebus (κῆβος) meaning "monkey".[7]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2010) |

Slow lorises are strepsirrhine primates, a group which includes lemurs, galagos, and lorises, and pottos. They are thought to have diverged from the other strepsirrhines in Asia, India (before it joined with Asia), or Africa.[citation needed]

Slow lorises are most closely related to the southeast Asian slender lorises and the pottos from Africa.[citation needed]

Distribution and diversity

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2010) |

Slow lorises are found only in South and Southeast Asia.[citation needed]

Physical description

Slow lorises have a round head and a less pointed snout than the slender lorises.[8] They have large eyes and good night vision. Their tails are either short or absent,[9] while their spine has an extra vertebra, which allows them greater mobility when twisting and extending towards nearby branches.[10] The intermembral index averages 89, meaning the front and back limbs are nearly equal in length. The second digit of the hand is short compared to the other digits, and its sturdy thumb helps to act like a clamp when digits three, four, and five grasp the opposite side of a tree branch. Both hands and feet provide a powerful grasp,[11] which can be held for hours without losing sensation due to the presence of a retia mirabilia (network of capillaries), a trait shared among all members of the lorisine subfamily.[8]

Slow lorises have an unusually low basal metabolic rate. This may be as little as 40% of the typical value for placental mammals of their size, comparable to that of sloths. Since they consume a relatively high calorie diet that is available year round, it has been proposed that this slow metabolism is due primarily to the need to eliminate toxic compounds from their food. For example, slow lorises can feed on Gluta bark, which can be fatal to humans.[12]

Behavior and ecology

Diet

Slow lorises are omnivores, eating insects, arthropods, small birds and reptiles, eggs, fruits, gums, nectar and other vegetation.[13][14][15][16] A 1984 study of the Sunda Slow Loris indicated that its diet consists of 71% fruit and gums and 29% insects and other animal prey.[13][14][17] A more detailed study of a different Sunda Slow Loris population in 2002 and 2003 showed very different dietary proportions. This study showed a diet consisting of 43.3% gum, 31.7% nectar, 22.5% fruit and just 2.5% anthropods and other animal prey.[13] The most common dietary item was nectar from flowers of the Bertram palm (Eugeissona tristis).[13] The Sunda Slow Loris eats insects which other predators avoid due to their repugnant taste or smell.[14] Captive slow lorises eat a wide variety of foods including bananas and other fruits, rice, dog-food, raw horse meat, insects, lizards, freshly killed chicken, mice, young hamsters and milk formula that is made by mixing instant baby food with egg and honey.[16] Captive slow loris diets may be supplemented with cod-liver oil and bone meal.[16]

Preliminary results of studies on the Pygmy Slow Loris indicates that its diet consists primarily of gums and nectar (especially nectar from Saraca dives flowers, and that animal prey makes up 30%–40% of its diet.[13][18] However, one 2002 analysis of Pygmy Loris feces indicated that it contained 98% insect remains and just 2% plant remains.[16] The Pygmy Slow Loris returns to the same gum feeding sites often and leaves conspicuous gouges on tree trunks when inducing the flow of exudates.[13][18] Captive Pygmy Slow Lorises also make characteristic gouge marks in wooden substrate.[16] It is not known how the sympatric Pygmy and Bengal Slow Loris partition their feeding niches.[13]

Slow lorises can eat while hanging upside down from a branch with both hands.[14] They spend about 20% of their nightly activities feeding.[18]

Social systems

Little is known about the social structure of slow lorises, but they generally spend most of the night foraging alone.[18][14] Slow lorises sleep during the day, usually alone but occasionally with other slow lorises.[18] There is significant overlap between the home ranges of adults, and males may have larger home ranges than females.[18][14] In the absence of direct studies of slow lorises, Simon Bearder speculated that slow loris social behavior is similar to the Potto, another slow moving nocturnal primate.[19] Such a social system is distinguished by a lack of matriarchy and by factors that allow the slow loris to remain inconspicuous and minimize energy expenditure, by limiting vocal exchanges and alarm calls and by scent marking being the dominant form of communication.[19]

Predator avoidance

Slow lorises can produce a toxin which they mix with their saliva to use as protection against enemies. The toxin is similar to the allergen in cat dander.[20] Loris bites cause a painful swelling, but the toxin is mild and not fatal. Cases of human death have been due to anaphylactic shock.[21]

Reproduction

Studies suggest that slow lorises are polygynandrous.[22] Infants are either parked on branches while their parents find food or else are carried by one of the parents.[23]

Due to their long gestations, small litter sizes, low birth weights, long weaning times, and long gaps between births, slow loris populations have one of the slowest growth rates among mammals of similar size.[24]

Conservation

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2010) |

Slow lorises are threatened by deforestation, the exotic pet trade, and traditional medicine.[25] All species are listed either as "Vulnerable" or "Endangered" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The slow loris has become a popular but illegal pet, mostly in Japan, but also in the United States.[25] Its popularity has swelled due to popular YouTube videos showing them being tickled.[10]

References

- ^ a b Groves 2005, pp. 122–123.

- ^ "Appendices I, II and III" (PDF). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). 2010.

- ^ Management Authority of Cambodia (3–15 June 2007). Notification to Parties: Consideration of Proposals for Amendment of Appendices I and II. Netherlands: CITES. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Black, R. (8 June 2007). "Too cute for comfort". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Nekaris & Munds 2010, p. 393.

- ^ "Lesser Slow loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Palmer 1904, p. 465.

- ^ a b Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 80.

- ^ McGreal 2007a.

- ^ a b Adam, D. (9 July 2009). "The eyes may be cute but the elbows are lethal". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 82.

- ^ Wiens, Zitzmann & Hussein 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nekaris & Bearder 2007, pp. 28–33.

- ^ a b c d e f Rowe 1996, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Menon 2009, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Schulze, H. "Nutrition of lorises and pottos". Loris and potto conservation database. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Bearder 1987, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f "Slow loris Nycticebus". National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin – Madison. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b Bearder 1987, p. 22.

- ^ Hagey, Fry & Fitch-Snyder 2007.

- ^ Wilde 1972.

- ^ Nekaris & Bearder 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 83.

- ^ Starr et al. 2010, p. 22.

- ^ a b National Geographic News: Top 5 Winners, Losers of the New Animal Trade

Literature cited

- Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-372576-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Bearder, Simon K. (1987). "Lorises, Bushbabies, and Tarsiers: Diverse Societies in Solitary Foragers". Primate Societies. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76716-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 111–184. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34810-0_12, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1007/978-0-387-34810-0_12instead. (subscription required)

- McGreal, S. (2007a). "Loris Confiscations Highlight Need for Protection" (PDF). IPPL News. 34 (1). International Primate Protection League: 3. ISSN 1040-3027. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Menon, Vivek (2009). Mammals of India. Princeton University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-691-14067-4.

- Nekaris, N.A.I.; Bearder, S.K. (2007). "Chapter 3: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, C.A.; MacKinnon, K.; P{anger, M.; Stumpf, R. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. U.S.A.: Oxford University Press. pp. 28–33. ISBN 978-0195171334.

- Nekaris, N.A.I.; Bearder, S.K. (2010). "Chapter 4: The Lorisiform Primates of Asia and Mainland Africa: Diversity Shrouded in Darkness". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, C.A.; MacKinnon, K.; Bearder, S.; Stumpf, R. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. U.S.A.: Oxford University Press. pp. 34–54. ISBN 978-0195390438.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3_22, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3_22instead.

- Palmer, T.S. (1904). Index Generum Mammalium: A List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. Washington: G.P.O. OCLC 1912921.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Rowe, Noel (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. Pogonias Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.3354/esr00285, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.3354/esr00285instead.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-007R1.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-007R1.1instead.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 5075669, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 5075669instead. (subscription required)

External links

- Primate Fact Sheets: Slow loris (Nycticebus) – Primate Info Net

- Slow Loris fact sheets – Duke University, USA

- loris-conservation.org – provides links to websites related to conservation of Asian lorises and African pottos