Chinese whispers

| Genres | Children's games |

|---|---|

| Players | Three or more |

| Setup time | None |

| Playing time | User determined |

| Chance | Medium |

| Skills | Speaking, listening |

Chinese whispers (some Commonwealth English), or telephone (American English and Canadian English),[1] is an internationally popular children's game in which messages are whispered from person to person and then the original and final messages are compared.[2] This sequential modification of information is called transmission chaining in the context of cultural evolution research, and is primarily used to identify the type of information that is more easily passed on from one person to another.[3]

Players form a line or circle, and the first player comes up with a message and whispers it to the ear of the second person in the line. The second player repeats the message to the third player, and so on. When the last player is reached, they announce the message they just heard, to the entire group. The first person then compares the original message with the final version. Although the objective is to pass around the message without it becoming garbled along the way, part of the enjoyment is that, regardless, this usually ends up happening. Errors typically accumulate in the retellings, so the statement announced by the last player differs significantly from that of the first player, usually with amusing or humorous effect. Reasons for changes include anxiousness or impatience, erroneous corrections, or the difficult-to-understand mechanism of whispering.

The game is often played by children as a party game or on the playground. It is often invoked as a metaphor for cumulative error, especially the inaccuracies as rumours or gossip spread,[1] or, more generally, for the unreliability of typical human recollection.

Etymology[edit]

United Kingdom, Australian, and New Zealand usage[edit]

In the UK, Australia and New Zealand, the game is typically called "Chinese whispers"; in the UK, this is documented from 1964.[4][5]

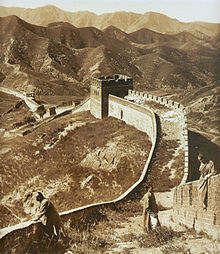

Various reasons have been suggested for naming the game after the Chinese, but there is no concrete explanation.[6] One suggested reason is a widespread British fascination with Chinese culture in the 18th and 19th centuries during the Enlightenment.[citation needed] Another theory posits that the game's name stems from the supposed confused messages created when a message was passed verbally from tower to tower along the Great Wall of China.[6]

Critics who focus on Western use of the word Chinese as denoting "confusion" and "incomprehensibility" look to the earliest contacts between Europeans and Chinese people in the 17th century, attributing it to a supposed inability on the part of Europeans to understand China's culture and worldview.[7] In this view, using the phrase "Chinese whispers" is taken as evidence of a belief that the Chinese language itself is not understandable.[8] Yunte Huang, a professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has said that: "Indicating inaccurately transmitted information, the expression 'Chinese Whispers' carries with it a sense of paranoia caused by espionage, counterespionage, Red Scare, and other war games, real or imaginary, cold or hot."[9] Usage of the term has been defended as being similar to other expressions such as "It's all Greek to me" and "Double Dutch".[10]

Alternative names[edit]

As the game is popular among children worldwide, it is also known under various other names depending on locality, such as Russian scandal,[11] whisper down the lane, broken telephone, operator, grapevine, gossip, secret message, the messenger game, and pass the message, among others.[1] In Turkey, this game is called kulaktan kulağa, which means "from (one) ear to (another) ear". In France, it is called téléphone arabe ("Arabic telephone") or téléphone sans fil ("wireless telephone").[12] In Germany the game is known as Stille Post ("quiet mail"). In Poland it is called głuchy telefon, meaning "deaf telephone". In Medici-era Florence it was called the "game of the ear".[13]

The game has also been known in English as Russian Scandal, Russian Gossip and Russian Telephone.[9]

In North America, the game is known under the name telephone.[14] Alternative names used in the United States include Broken Telephone, Gossip, and Rumors.[15] This North American name is followed in a number of languages where the game is known by the local language's equivalent of "broken telephone", such in Malaysia as telefon rosak, in Israel as telefon shavur (טלפון שבור), in Finland as rikkinäinen puhelin, and in Greece as halasmeno tilefono (χαλασμένο τηλέφωνο).

Game[edit]

The game has no winner: the entertainment comes from comparing the original and final messages. Intermediate messages may also be compared; some messages will become unrecognizable after only a few steps.

As well as providing amusement, the game can have educational value. It shows how easily information can become corrupted by indirect communication. The game has been used in schools to simulate the spread of gossip and its possible harmful effects.[16] It can also be used to teach young children to moderate the volume of their voice,[17] and how to listen attentively;[18] in this case, a game is a success if the message is transmitted accurately with each child whispering rather than shouting. It can also be used for older or adult learners of a foreign language, where the challenge of speaking comprehensibly, and understanding, is more difficult because of the low volume, and hence a greater mastery of the fine points of pronunciation is required.[19]

Notable games[edit]

In 2008 1,330 children and celebrities set a world record for the game of Chinese Whispers involving the most people. The game was held at the Emirates Stadium in London and lasted two hours and four minutes. Starting with "together we will make a world of difference", the phrase morphed into "we're setting a record" part way down the chain, and by the end had become simply "haaaaa". The previous record, set in 2006 by the Cycling Club of Chengdu, China, had involved 1,083 people.[20][21]

In 2017 a new world record was set for the largest game of Chinese Whispers in terms of the number of participants by schoolchildren in Tauranga, New Zealand. The chain involved 1,763 school children and other individuals and was held as part of Hearing Week 2017. The starting phrase was "Turn it down".[22] As of 2022 this remained the world record for the largest game of Chinese Whispers by number of participants according to the Guinness Book of Records.[23]

In 2012 a global game of Chinese Whispers was played spanning 237 individuals speaking seven different languages. Beginning in St Kilda Library in Melbourne, Australia, the starting phrase "Life must be lived as play" (a paraphrase of Plato) had become "He bites snails" by the time the game reached its end in Alaska 26 hours later.[24][25] In 2013, the Global Gossip Game had 840 participants and travelled to all 7 continents.[26]

Variants[edit]

A variant of Chinese Whispers is called Rumors. In this version of the game, when players transfer the message, they deliberately change one or two words of the phrase (often to something more humorous than the previous message). Intermediate messages can be compared. There is a second derivative variant, no less popular than Rumors, known as Mahjong Secrets (UK), or Broken Telephone (US), where the objective is to receive the message from the whisperer and whisper to the next participant the first word or phrase that comes to mind in association with what was heard. At the end, the final phrase is compared to the first in front of all participants.[citation needed]

The pen-and-paper game Telephone Pictionary (also known as Eat Poop You Cat[27]) is played by alternately writing and illustrating captions, the paper being folded so that each player can only see the previous participant's contribution.[28] The game was first implemented online by Broken Picture Telephone in early 2007.[29] Following the success of Broken Picture Telephone,[30] commercial boardgame versions Telestrations[27] and Cranium Scribblish were released two years later in 2009. Drawception, and other websites, also arrived in 2012.

A translation relay is a variant in which the first player produces a text in a given language, together with a basic guide to understanding, which includes a lexicon, an interlinear gloss, possibly a list of grammatical morphemes, comments on the meaning of difficult words, etc. (everything except an actual translation). The text is passed on to the following player, who tries to make sense of it and casts it into their language of choice, then repeating the procedure, and so on. Each player only knows the translation done by his immediate predecessor, but customarily the relay master or mistress collects all of them. The relay ends when the last player returns the translation to the beginning player.

Another variant of Chinese whispers is shown on Ellen's Game of Games under the name of Say Whaaat?. However, the difference is that the four players will be wearing earmuffs; therefore the players have to read their lips. A similar game, Shouting One Out, in which participants wearing noise-canceling headphones had to interpret the lip movements of the preceding player, appeared in multiple editions of the ITV2 panel game series Celebrity Juice.

The CBBC game show Copycats featured several rounds played in a Chinese whispers format, in which each player on a team in turn had to interpret and recreate the mimed actions, drawing or music performed by the preceding person in line, with the points value awarded based on how far down the line the correct starting prompt had travelled before mutating into something else.

A party game variant of telephone known as "wordpass" involves saying words out loud and saying a related word, until a word is repeated.[citation needed]

As a metaphor[edit]

Chinese whispers is used in a number of fields as a metaphor for imperfect data transmission over multiple iterations.[31] For example the British zoologist Mark Ridley in his book Mendel's demon used Chinese Whispers as an analogy for the imperfect transmission of genetic information across multiple generations.[32][33] In another example, Richard Dawkins used Chinese Whispers as a metaphor for infidelity in memetic replication, referring specifically to children trying to reproduce drawing of a Chinese junk in his essay Chinese Junk and Chinese Whispers.[34][35] It was used in the movie Tár to represent gossip circling within an orchestra.

See also[edit]

- Drawception

- Exquisite corpse

- Generation loss

- Mondegreen

- Pavement radio

- Snowball effect

- Round-trip translation

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Blackmore, Susan J. (2000). The Meme Machine. Oxford University Press. p. x. ISBN 0-19-286212-X.

The form and timing of the tic undoubtedly mutated over the generations, as in the childhood game of Chinese Whispers (Americans call it telephone)

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mesoudi, A.; Whiten, A. (2008). "The multiple roles of cultural transmission experiments in understanding human cultural evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1509): 3489–3501. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0129. PMC 2607337. PMID 18801720.

- ^ Martin, Gary. "Phrase Finder: Chinese Whispers". Phrase Finder. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Strahan, Lachlan (June 1992). "'THE LUCK OF A CHINAMAN': IMAGES OF THE CHINESE IN POPULAR AUSTRALIAN SAYINGS" (PDF). East Asian History (3). Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University: 71. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b Chu, Ben (2013). Chinese Whispers Why Everything You've Heard About China is Wrong. Orion. p. Introduction. ISBN 9780297868460. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Dale, Corinne H. (2004). Chinese Aesthetics and Literature: A Reader. New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 15–25. ISBN 0-7914-6022-3.

- ^ Ballaster, Rosalind (2005). Fabulous Orients: fictions of the East in England, 1662–1785. Oxford University Press. pp. 202–3. ISBN 0-19-926733-2.

The sinophobic name points to a centuries-old tradition in Europe of representing spoken Chinese as an incomprehensible and unpronounceable combination of sounds.

- ^ a b Huang, Yunte (Spring 2015). "Chinese Whispers". Verge: Studies in Global Asias. 1 (1): 66–69. doi:10.5749/vergstudglobasia.1.1.0066. JSTOR 10.5749/vergstudglobasia.1.1.0066. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "MasterChef contestant under fire for using old saying 'Chinese whispers'". Starts at 60. 3 June 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Gryski, Camilla (1998). Let's Play: Traditional Games of Childhood, p.36. Kids Can. ISBN 1550744976.

- ^ "Le téléphone arabe : règle du jeu, origine, variantes et idées de phrase". Jeux et Compagnie (in French). 2011-11-13. Archived from the original on 2012-09-29. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

Arabic telephone, or the wireless telephone, consists of having a sentence created by the first player and then recited aloud by the last player after circulating rapidly by word of mouth through a line of players. The interest of the game is to compare the final version of the sentence with its initial version. Indeed, with the possible errors of articulation, pronunciation, confusions between words and sounds, the final sentence can be completely different from the initial one.

- ^ Murphy, Caroline P. (2008). Murder of a Medici Princess. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 157. ISBN 9780199839896. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Jonsson, Emelie; Carroll, Joseph; Clasen, Mathias (2020). Evolutionary Perspectives on Imaginative Culture. Springer. p. 284. ISBN 9783030461904. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Lovis, William A. (31 December 2011). Information and Its Role in Hunter-Gatherer Bands. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781938770203. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Jackman, John; Wendy Wren (1999). "Skills Unit 8: the Chinese princess". Nelson English Bk. 2 Teachers' Resource Book. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-17-424605-6.

Play 'Chinese Whispers' to demonstrate how word-of-mouth messages or stories quickly become distorted

- ^ Collins, Margaret (2001). Because We're Worth It: Enhancing Self-esteem in Young Children. Sage. p. 55. ISBN 1-873942-09-5.

Explain that speaking quietly can be more effective in communication than shouting, although clarity is important. You could play "Chinese Whispers" to illustrate this!

- ^ Barrs, Kathie (1994). music works: music education in the classroom with children from five to nine years. Belair. p. 48. ISBN 0-947882-28-6.

Listening skills:...Play Chinese Whispers

- ^ For example, see Hill, op. cit.; or Morris, Peter; Alan Wesson (2000). Lernpunkt Deutsch.: students' book. Nelson Thornes. p. viii. ISBN 0-17-440267-8.

Simple games for practising vocabulary and/or numbers: ... Chinese Whispers: ...the final word is compared with the first to see how similar (or not!) it is.

- ^ "Chinese whisper record in London". Gulf News. 12 July 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ McKenna, Jemma (5 November 2008). "Whisper it loud: the record was broken". Third Sector. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Psst! Can we beat a world record?". Sun Live. 1 March 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Largest game of Telephone". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Smith, Helen M.; Banks, Peter B. (2017). "How dangerous conservation ideas can develop through citation errors". Australian Zoologist. 38 (3): 409. doi:10.7882/az.2014.047. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "The final results!". Global Gossip Game website. 15 November 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Global Gossip Game 2013 – final results". Global Gossip Game website. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Eat Poop You Cat: A silly, fun, and free party game". annarbor.com. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Jones, Myfanwy (4 November 2010). Parlour Games for Modern Families. Penguin Adult. ISBN 9781846143472 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Nektan Slots Games & Other Communication Games - Broken Picture Telephone". www.brokenpicturetelephone.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- ^ "Best of Casual Gameplay 2009 - Simple Idea Results (browser games) - Jay is games". jayisgames.com. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- ^ Boeck, Angelica (2022). "Africanisation of the European - vulnerability and de-colonisation". In Kidenda, Mary Clare; Kriel, Lize; Wagner, Ernst (eds.). Visual Cultures of Africa. Waxmann. p. 225. ISBN 9783830945239. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Turney, Jon (1 May 2001). "From angelic sex to sinful genes". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Ridley, Mark (2000). Mendel's demon : gene justice and the complexity of life. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 56. ISBN 0297646346. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Sterelny, Kim (May 2004). "Never Apologize, Always Explain". BioScience. 24 (5): 460–462. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0460:NAAE]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86360983.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2003). A devil's chaplain : selected essays. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 119. ISBN 0297829734. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

External links[edit]

- Broken Picture Telephone, an online game based on Chinese Whispers; recently re-activated

- Global Gossip Game, a game of gossip that passes from library to library around the world on International Games Day at local libraries

- The Misemotions Game Archived 2016-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, a variation of Chinese Whispers where participants have to properly convey emotions instead of text messages