Cyrus the Great

| Cyrus the Great 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire | |

| Reign | 550–530 BC |

| Predecessor | Empire established |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| King of Persia | |

| Reign | 559–530 BC |

| Predecessor | Cambyses I |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| King of Media | |

| Reign | 549–530 BC |

| Predecessor | Astyages |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| King of Lydia | |

| Reign | 547–530 BC |

| Predecessor | Croesus |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| King of Babylon | |

| Reign | 539–530 BC |

| Predecessor | Nabonidus |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| Born | c. 600 BC[2] Anshan, Persis (present-day Fars Province, Iran) |

| Died | 4 December 530 BC[3] (aged 70) Pasargadae, Persis |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Cassandane |

| Issue |

|

| House | Teispid |

| Father | Cambyses I |

| Mother | Mandane of Media |

Cyrus II of Persia (Old Persian: 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 Kūruš; c. 600–530 BC),[a] commonly known as Cyrus the Great,[4] was the founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire.[5] Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Median Empire and embracing all of the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East,[5] expanding vastly and eventually conquering most of West Asia and much of Central Asia to create what would soon become the largest polity in human history at the time.[5] Widely considered the world's first superpower, the Achaemenid Empire's largest territorial extent was achieved under Darius the Great, whose rule stretched from the Balkans (Eastern Bulgaria–Paeonia and Thrace–Macedonia) and the rest of Southeast Europe in the west to the Indus Valley in the east.

After conquering the Median empire, Cyrus led the Achaemenids to conquer the Lydian Empire and eventually the Neo-Babylonian Empire. He also led an expedition into Central Asia, which resulted in major military campaigns that were described as having brought "into subjection every nation without exception";[6] Cyrus allegedly died in battle with the Massagetae, a nomadic Eastern Iranian tribal confederation, along the Syr Darya in December 530 BC.[7][b] However, Xenophon of Athens claimed that Cyrus did not die fighting and had instead returned to the city of Persepolis, which served as the Achaemenid ceremonial capital.[8] He was succeeded by his son Cambyses II, whose campaigns into North Africa led to the conquests of Egypt, Nubia, and Cyrenaica during his short rule.

To the Greeks, he was known as Cyrus the Elder (Greek: Κῦρος ὁ Πρεσβύτερος Kŷros ho Presbýteros). Cyrus was particularly renowned among contemporary scholars because of his habitual policy of respecting peoples' customs and religions in the lands that he conquered.[9] He was influential in developing the system of a central administration at Pasargadae to govern the Achaemenid Empire's border satraps, which worked for the profit of both rulers and subjects.[5][10] Following the Achaemenid conquest of Babylon, Cyrus issued the Edict of Restoration, in which he authorized and encouraged the return of the Jewish people to what had been the Kingdom of Judah, officially ending the Babylonian captivity. He is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and left a lasting legacy on Judaism due to his role in facilitating the return to Zion, a migratory event in which the Jews returned to the Land of Israel following Cyrus' establishment of Yehud Medinata and subsequently rebuilt the Temple in Jerusalem, which had been destroyed by the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem. According to Chapter 45:1 of the Book of Isaiah,[11] Cyrus was anointed by the Jewish God for this task as a biblical messiah; he is the only non-Jewish figure to be revered in this capacity.[12]

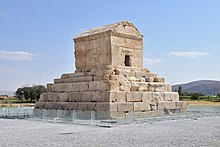

In addition to his influence on the traditions of both the Eastern world and the Western world, Cyrus is also recognized for his achievements in human rights, politics, and military strategy. The Achaemenid Empire's prestige in the ancient world would eventually extend as far west as Athens, where upper-class Greeks adopted aspects of the culture of the ruling Persian class as their own.[13] As the founder of the first Persian empire, Cyrus played a crucial role in defining the national identity of the Iranian nation; the Achaemenid Empire was instrumental in spreading the ideals of Zoroastrianism as far east as China.[14][15][16] He remains a cult figure in modern-day Iran, with the Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae serving as a spot of reverence for millions of the country's citizens.[17]

Etymology[edit]

The name Cyrus is a Latinized form derived from the Greek-language name Κῦρος (Kỹros), which itself was derived from the Old Persian name Kūruš.[18][19] The name and its meaning have been recorded within ancient inscriptions in different languages. The ancient Greek historians Ctesias and Plutarch stated that Cyrus was named from the Sun (Kuros), a concept which has been interpreted as meaning "like the Sun" (Khurvash) by noting its relation to the Persian noun for Sun, khor, while using -vash as a suffix of likeness.[20] Karl Hoffmann has suggested a translation based on the meaning of an Indo-European root "to humiliate", and accordingly, the name "Cyrus" means "humiliator of the enemy in verbal contest".[19] Another possible Iranian derivation would mean "the young one, child", similar to Kurdish kur ("son, little boy") or Ossetian i-gur-un ("to be born") and kur (young bull).[21] In the Persian language and especially in Iran, Cyrus' name is spelled as کوروش (Kūroš, [kuːˈɾoʃ]).[22] In the Bible, he is referred to in the Hebrew language as Koresh (כורש).[23] Some pieces of evidence suggest that Cyrus is Kay Khosrow, a legendary Persian king of the Kayanian dynasty and a character in Shahnameh, a Persian epic.[24]

Some scholars, however, believe that neither Cyrus nor Cambyses were Iranian names, proposing that Cyrus was Elamite[25] in origin and that the name meant "he who bestows care" in the extinct Elamite language.[26] One reason is that, while Elamite names may end in -uš, no Elamite texts spell the name this way — only Kuraš.[21] Meanwhile, Old Persian did not allow names to end in -aš, so it would make sense for Persian speakers to change an original Kuraš into the more grammatically correct form Kuruš.[21] Elamite scribes, on the other hand, would not have had a reason to change an original Kuraš into Kuruš, since both forms were acceptable.[21] Therefore, Kuraš probably represents the original form.[21] Another scholarly opinion is that Kuruš was a name of Indo-Aryan origin, in honour of the Indo-Aryan Kuru and Kamboja mercenaries from eastern Afghanistan and Northwest India that helped in the conquest of the Middle East.[27][28] [c]

Dynastic history[edit]

The Persian domination and kingdom in the Iranian plateau started as an extension of the Achaemenid dynasty, who expanded their earlier dominion possibly from the 9th century BC onward. The eponymous founder of the dynasty was Achaemenes (from Old Persian Haxāmaniš). Achaemenids are "descendants of Achaemenes", as Darius the Great, the ninth king of the dynasty, traced his ancestry to him, declaring "for this reason, we are called Achaemenids". Achaemenes built the state of Parsumash in the southwest of Iran and was succeeded by Teispes, who took the title "King of Anshan" after seizing the city Anshan and enlarging his kingdom further to include Pars proper.[32] Ancient documents[33] mention that Teispes had a son called Cyrus I, who also succeeded his father as "king of Anshan". Cyrus I had a full brother whose name is recorded as Ariaramnes.[5]

In 600 BC, Cyrus I was succeeded by his son, Cambyses I, who reigned until 559 BC. Cyrus II "the Great" was a son of Cambyses I, who had named his son after his father, Cyrus I.[34] There are several inscriptions of Cyrus the Great and later kings that refer to Cambyses I as the "great king" and "king of Anshan". Among these are some passages in the Cyrus cylinder where Cyrus calls himself "son of Cambyses, great king, king of Anshan". Another inscription (from CM's) mentions Cambyses I as a "mighty king" and "an Achaemenian", which according to the bulk of scholarly opinion was engraved under Darius and considered as a later forgery by Darius.[35][36] However, Cambyses II's maternal grandfather Pharnaspes is named by historian Herodotus as "an Achaemenian".[37] Xenophon's account in his Cyropædia names Cambyses's wife as Mandane and mentions Cambyses as king of Iran (ancient Persia). These agree with Cyrus's own inscriptions, as Anshan and Parsa were different names for the same land. These also agree with other non-Iranian accounts, except on one point from Herodotus which states that Cambyses was not a king but a "Persian of good family".[38] However, in some other passages, Herodotus' account is wrong also on the name of the son of Chishpish, which he mentions as Cambyses but according to modern scholars, should be Cyrus I.[39]

The traditional view based on archaeological research and the genealogy given in the Behistun Inscription and by Herodotus[5] holds that Cyrus the Great was an Achaemenid. However, M. Waters has suggested that Cyrus is unrelated to the Achaemenids or Darius the Great, and that his family was of Teispid and Anshanite origin instead of Achaemenid.[40]

Early life[edit]

Cyrus was born to Cambyses I, King of Anshan, and Mandane, daughter of Astyages, King of Media, during the period of 600–599 BC.

By his own account, generally believed now to be accurate, Cyrus was preceded as king by his father Cambyses I, grandfather Cyrus I, and great-grandfather Teispes.[42] Cyrus married Cassandane[citation needed] who was an Achaemenian and the daughter of Pharnaspes who bore him two sons, Cambyses II and Bardiya along with three daughters, Atossa, Artystone, and Roxane.[citation needed] Cyrus and Cassandane were known to love each other very much – Cassandane said that she found it more bitter to leave Cyrus than to depart her life.[43] After her death, Cyrus insisted on public mourning throughout the kingdom.[44] The Nabonidus Chronicle states that Babylonia mourned Cassandane for six days (identified as 21–26 March 538 BC).[45] After his father's death, Cyrus inherited the Persian throne at Pasargadae, which was a vassal of Astyages. The Greek historian Strabo has said that Cyrus was originally named Agradates[26] by his step-parents. It is possible that, when reuniting with his original family, following the naming customs, Cyrus's father, Cambyses I, named him Cyrus after his grandfather, who was Cyrus I.[citation needed] There is also an account by Strabo that claimed Agradates adopted the name Cyrus after the Cyrus river near Pasargadae.[26]

Mythology[edit]

Herodotus gave a mythological account of Cyrus's early life. In this account, Astyages had two prophetic dreams in which a flood, and then a series of fruit-bearing vines, emerged from his daughter Mandane's pelvis, and covered the entire kingdom. These were interpreted by his advisers as a foretelling that his grandson would one day rebel and supplant him as king. Astyages summoned Mandane, at the time pregnant with Cyrus, back to Ecbatana to have the child killed. His general Harpagus delegated the task to Mithradates, one of the shepherds of Astyages, who raised the child and passed off his stillborn son to Harpagus as the dead infant Cyrus.[46] Cyrus lived in secrecy, but when he reached the age of 10, during a childhood game, he had the son of a nobleman beaten when he refused to obey Cyrus' commands. As it was unheard of for the son of a shepherd to commit such an act, Astyages had the boy brought to his court, and interviewed him and his adoptive father. Upon the shepherd's confession, Astyages sent Cyrus back to Persia to live with his biological parents.[47] However, Astyages summoned the son of Harpagus, and in retribution, chopped him to pieces, roasted some portions while boiling others, and tricked his adviser into eating his child during a large banquet. Following the meal, Astyages's servants brought Harpagus the head, hands and feet of his son on platters, so he could realize his inadvertent cannibalism.[48]

Rise and military campaigns[edit]

Median Empire[edit]

Cyrus the Great succeeded to the throne in 559 BC following his father's death; however, Cyrus was not yet an independent ruler. Like his predecessors, Cyrus had to recognize Median overlordship. Astyages, last king of the Median Empire and Cyrus's grandfather, may have ruled over the majority of the Ancient Near East, from the Lydian frontier in the west to the lands of the Parthians and Persians in the east.[citation needed]

According to the Nabonidus Chronicle, Astyages launched an attack against Cyrus, "king of Ansan". According to the historian Herodotus, it is known that Astyages placed Harpagus in command of the Median army to conquer Cyrus. However, Harpagus contacted Cyrus and encouraged his revolt against Media, before eventually defecting along with several of the nobility and a portion of the army. This mutiny is confirmed by the Nabonidus Chronicle. The Chronicle suggests that the hostilities lasted for at least three years (553–550 BC), and the final battle resulted in the capture of Ecbatana. This was described in the paragraph that preceded the entry for Nabonidus's year 7, which detailed Cyrus's victory and the capture of his grandfather.[49] According to the historians Herodotus and Ctesias, Cyrus spared the life of Astyages and married his daughter, Amytis. This marriage pacified several vassals, including the Bactrians, Parthians, and Saka.[50] Herodotus notes that Cyrus also subdued and incorporated Sogdia into the empire during his military campaigns of 546–539 BC.[51][52]

With Astyages out of power, all of his vassals (including many of Cyrus's relatives) were now under his command. His uncle Arsames, who had been the king of the city-state of Parsa under the Medes, therefore would have had to give up his throne. However, this transfer of power within the family seems to have been smooth, and it is likely that Arsames was still the nominal governor of Parsa under Cyrus's authority—more a Prince or a Grand Duke than a King.[53] His son, Hystaspes, who was also Cyrus's second cousin, was then made satrap of Parthia and Phrygia. Cyrus the Great thus united the twin Achaemenid kingdoms of Parsa and Anshan into Persia proper. Arsames lived to see his grandson become Darius the Great, Shahanshah of Persia, after the deaths of both of Cyrus's sons.[54] Cyrus's conquest of Media was merely the start of his wars.[55]

Lydian Empire and Asia Minor[edit]

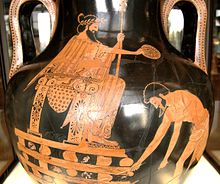

The exact dates of the Lydian conquest are unknown, but it must have taken place between Cyrus's overthrow of the Median kingdom (550 BC) and his conquest of Babylon (539 BC). It was common in the past to give 547 BC as the year of the conquest due to some interpretations of the Nabonidus Chronicle, but this position is currently not much held.[56] The Lydians first attacked the Achaemenid Empire's city of Pteria in Cappadocia. The king of Lydia Croesus besieged and captured the city enslaving its inhabitants. Meanwhile, the Persians invited the citizens of Ionia who were part of the Lydian kingdom to revolt against their ruler. The offer was rebuffed, and thus Cyrus levied an army and marched against the Lydians, increasing his numbers while passing through nations in his way. The Battle of Pteria was effectively a stalemate, with both sides suffering heavy casualties by nightfall. Croesus retreated to Sardis the following morning.[57]

While in Sardis, Croesus sent out requests for his allies to send aid to Lydia. However, near the end of the winter, before the allies could unite, Cyrus the Great pushed the war into Lydian territory and besieged Croesus in his capital, Sardis. Shortly before the final Battle of Thymbra between the two rulers, Harpagus advised Cyrus the Great to place his dromedaries in front of his warriors; the Lydian horses, not used to the dromedaries' smell, would be very afraid. The strategy worked; the Lydian cavalry was routed. Cyrus defeated and captured Croesus. Cyrus occupied the capital at Sardis, conquering the Lydian kingdom in 546 BC.[57] According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great spared Croesus's life and kept him as an advisor, but this account conflicts with some translations of the contemporary Nabonidus Chronicle which interpret that the king of Lydia was slain.[58]

Before returning to the capital, Commagene was incorporated into Persia in 546 BC.[59] Later, a Lydian named Pactyas was entrusted by Cyrus the Great to send Croesus's treasury to Persia. However, soon after Cyrus's departure, Pactyas hired mercenaries and caused an uprising in Sardis, revolting against the Persian satrap of Lydia, Tabalus. Cyrus sent Mazares, one of his commanders, to subdue the insurrection but demanded that Pactyas be returned alive. Upon Mazares's arrival, Pactyas fled to Ionia, where he had hired more mercenaries. Mazares marched his troops into the Greek country and subdued the cities of Magnesia and Priene. The fate of Pactyas is unknown, but after capture, he was probably sent to Cyrus and put to death after being tortured.[60]

Mazares continued the conquest of Asia Minor but died of unknown causes during his campaign in Ionia. Cyrus sent Harpagus to complete Mazares's conquest of Asia Minor. Harpagus captured Lycia, Aeolia and Caria, using the technique of building earthworks to breach the walls of besieged cities, a method unknown to the Greeks. He ended his conquest of the area in 542 BC and returned to Persia.[61]

Eastern Campaigns[edit]

After the conquest of Lydia, Cyrus campaigned in the east between around 545 BC to 540 BC. Cyrus first tried to conquer Gedrosia, however he was decisively defeated and departed Gedrosia.[62] Gedrosia was most likely conquered during the reign of Darius I. After the failed attempt to conquer Gedrosia, Cyrus attacked the regions of Bactria, Arachosia, Sogdia, Saka, Chorasmia, Margiana and other provinces in the east. In 533 BC, Cyrus the Great crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and collected tribute from the Indus cities. Thus, Cyrus probably had established vassal states in western India.[63] Cyrus then returned with his army to Babylon due to the unrest taking place in and around Babylon.

Neo-Babylonian Empire[edit]

By the year 540 BC, Cyrus captured Elam and its capital, Susa.[64] The Nabonidus Chronicle records that, prior to the battle(s), the king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Nabonidus, had ordered cult statues from outlying Babylonian cities to be brought into the capital, suggesting that the conflict had begun possibly in the winter of 540 BC.[65] Just before October 539 BC, Cyrus fought the Battle of Opis in or near the strategic riverside city of Opis on the Tigris, north of Babylon. The Babylonian army was routed, and on 10 October, Sippar was seized without a battle, with little to no resistance from the populace.[66] It is probable that Cyrus engaged in negotiations with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation.[67] Nabonidus, who had retreated to Sippar following his defeat at Opis, fled to Borsippa.[68]

Around[69] 12 October,[70] Persian general Gubaru's troops entered Babylon, again without any resistance from the Babylonian armies, and detained Nabonidus.[71] Herodotus explains that to accomplish this feat, the Persians, using a basin dug earlier by the Babylonian queen Nitokris to protect Babylon against Median attacks, diverted the Euphrates river into a canal so that the water level dropped "to the height of the middle of a man's thigh", which allowed the invading forces to march directly through the river bed to enter at night.[72] Shortly thereafter, Nabonidus returned from Borsippa and surrendered to Cyrus.[73] On 29 October, Cyrus entered the city of Babylon.[74]

Prior to Cyrus's invasion of Babylon, the Neo-Babylonian Empire had conquered many kingdoms. In addition to Babylonia, Cyrus probably incorporated its sub-national entities into his Empire, including Syria, Judea, and Arabia Petraea, although there is no direct evidence to support this assumption.[3][75]

After taking Babylon, Cyrus the Great proclaimed himself "king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four corners of the world" in the famous Cyrus Cylinder, an inscription on a cylinder that was deposited in the foundations of the Esagila temple dedicated to the chief Babylonian god, Marduk. The text of the cylinder denounces Nabonidus as impious and portrays the victorious Cyrus as pleasing the god Marduk. It describes how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples, and restored temples and cult sanctuaries. Although some have asserted that the cylinder represents a form of human rights charter, historians generally portray it in the context of a long-standing Mesopotamian tradition of new rulers beginning their reigns with declarations of reforms.[76]

Cyrus the Great's dominions composed the largest empire the world had ever seen to that point.[77] At the end of Cyrus's rule, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from Asia Minor in the west to the Indus River in the east.[3]

Death[edit]

The details of Cyrus's death vary by account. Ctesias, in his Persica, has the longest account, which says Cyrus met his death while putting down resistance from the Derbices infantry, aided by other Scythian archers and cavalry, plus Indians and their war-elephants. According to him, this event took place northeast of the headwaters of the Syr Darya.[78] The account of Herodotus from his Histories provides the second-longest detail, in which Cyrus met his fate in a fierce battle with the Massagetae, a Scythian tribal confederation from the southern deserts of Khwarezm and Kyzyl Kum in the southernmost portion of the Eurasian Steppe regions of modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, following the advice of Croesus to attack them in their own territory.[79] The Massagetae were related to the Scythians in their dress and mode of living; they fought on horseback and on foot. In order to acquire her realm, Cyrus first sent an offer of marriage to their ruler, the empress Tomyris, a proposal she rejected.[citation needed]

He then commenced his attempt to take Massagetae territory by force (c. 529 BC),[81] beginning by building bridges and towered war boats along his side of the river Oxus, or Amu Darya, which separated them. Sending him a warning to cease his encroachment (a warning which she stated she expected he would disregard anyway), Tomyris challenged him to meet her forces in honorable warfare, inviting him to a location in her country a day's march from the river, where their two armies would formally engage each other. He accepted her offer, but, learning that the Massagetae were unfamiliar with wine and its intoxicating effects, he set up and then left camp with plenty of it behind, taking his best soldiers with him and leaving the least capable ones.[citation needed]

The general of Tomyris's army, Spargapises, who was also her son, and a third of the Massagetian troops, killed the group Cyrus had left there and, finding the camp well stocked with food and the wine, unwittingly drank themselves into inebriation, diminishing their capability to defend themselves when they were then overtaken by a surprise attack. They were successfully defeated, and, although he was taken prisoner, Spargapises committed suicide once he regained sobriety. Upon learning of what had transpired, Tomyris denounced Cyrus's tactics as underhanded and swore vengeance, leading a second wave of troops into battle herself. Cyrus the Great was ultimately killed, and his forces suffered massive casualties in what Herodotus referred to as the fiercest battle of his career and the ancient world. When it was over, Tomyris ordered the body of Cyrus brought to her, then decapitated him and dipped his head in a vessel of blood in a symbolic gesture of revenge for his bloodlust and the death of her son.[79][82] However, some scholars question this version, mostly because even Herodotus admits this event was one of many versions of Cyrus's death that he heard from a supposedly reliable source who told him no one was there to see the aftermath.[83]

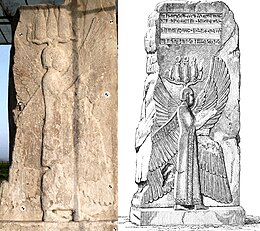

Herodotus also recounts that Cyrus saw in his sleep the oldest son of Hystaspes (Darius I) with wings upon his shoulders, shadowing with the one wing Asia, and with the other wing Europe.[84] Archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan explains this statement by Herodotus and its connection with the four winged bas-relief figure of Cyrus the Great in the following way:[84]

Herodotus therefore, as I surmise, may have known of the close connection between this type of winged figure and the image of Iranian majesty, which he associated with a dream prognosticating the king's death before his last, fatal campaign across the Oxus.

Muhammad Dandamayev says that Persians may have taken Cyrus's body back from the Massagetae, unlike what Herodotus claimed.[3]

According to the Chronicle of Michael the Syrian (AD 1166–1199) Cyrus was killed by his wife Tomyris, queen of the Massagetae (Maksata), in the 60th year of Jewish captivity.[85]

An alternative account from Xenophon's Cyropaedia contradicts the others, claiming that Cyrus died peacefully at his capital.[86] The final version of Cyrus's death comes from Berossus, who only reports that Cyrus met his death while warring against the Dahae archers northwest of the headwaters of the Syr Darya.[87]

Burial[edit]

Cyrus the Great's remains may have been interred in his capital city of Pasargadae, where today a limestone tomb (built around 540–530 BC[88]) still exists, which many believe to be his. Strabo and Arrian give nearly identical descriptions of the tomb, based on the eyewitness report of Aristobulus of Cassandreia, who at the request of Alexander the Great visited the tomb twice.[89] Though the city itself is now in ruins, the burial place of Cyrus the Great has remained largely intact, and the tomb has been partially restored to counter its natural deterioration over the centuries. According to Plutarch, his epitaph read:

O man, whoever you are and wherever you come from, for I know you will come, I am Cyrus who won the Persians their empire. Do not therefore begrudge me this bit of earth that covers my bones.[90]

Cuneiform evidence from Babylon proves that Cyrus died around December 530 BC,[91] and that his son Cambyses II had become king. Cambyses continued his father's policy of expansion, and captured Egypt for the Empire, but soon died after only seven years of rule. He was succeeded either by Cyrus's other son Bardiya or an impostor posing as Bardiya, who became the sole ruler of Persia for seven months, until he was killed by Darius the Great.[92]

The translated ancient Roman and Greek accounts give a vivid description of the tomb both geometrically and aesthetically; the tomb's geometric shape has changed little over the years, still maintaining a large stone of quadrangular form at the base, followed by a pyramidal succession of smaller rectangular stones, until after a few slabs, the structure is curtailed by an edifice, with an arched roof composed of a pyramidal shaped stone, and a small opening or window on the side, where the slenderest man could barely squeeze through.[93]

Within this edifice was a golden coffin, resting on a table with golden supports, inside of which the body of Cyrus the Great was interred. Upon his resting place, was a covering of tapestry and drapes made from the best available Babylonian materials, utilizing fine Median worksmanship; below his bed was a fine red carpet, covering the narrow rectangular area of his tomb.[93] Translated Greek accounts describe the tomb as having been placed in the fertile Pasargadae gardens, surrounded by trees and ornamental shrubs, with a group of Achaemenian protectors called the "Magi", stationed nearby to protect the edifice from theft or damage.[93][94]

Years later, in the chaos created by Alexander the Great's invasion of Persia and after the defeat of Darius III, Cyrus the Great's tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by the manner in which the tomb was treated, and questioned the Magi and put them to court.[93] On some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more about his attempt to undermine their influence and his show of power in his newly conquered empire, than a concern for Cyrus's tomb.[95] However, Alexander admired Cyrus, from an early age reading Xenophon's Cyropaedia, which described Cyrus's heroism in battle and governance as a king and legislator.[96] Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus to improve the tomb's condition and restore its interior.[93] Despite his admiration for Cyrus the Great, and his attempts at renovation of his tomb, Alexander had, six years previously (330 BC), sacked Persepolis, the opulent city that Cyrus may have chosen the site for, and either ordered its burning as an act of pro-Greek propaganda or set it on fire during drunken revels.[97]

The edifice has survived the test of time, through invasions, internal divisions, successive empires, regime changes, and revolutions. The last prominent Persian figure to bring attention to the tomb was Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (Shah of Iran) the last official monarch of Persia, during his celebrations of 2,500 years of monarchy. Just as Alexander the Great before him, the Shah of Iran wanted to appeal to Cyrus's legacy to legitimize his own rule by extension.[98] The United Nations recognizes the tomb of Cyrus the Great and Pasargadae as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[88]

Legacy[edit]

British historian Charles Freeman suggests that "In scope and extent his achievements [Cyrus] ranked far above that of the Macedonian king, Alexander, who was to demolish the [Achaemenid] empire in the 320s but fail to provide any stable alternative."[99] Cyrus has been a personal hero to many people, including Thomas Jefferson, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and David Ben-Gurion.[100]

The achievements of Cyrus the Great throughout antiquity are reflected in the way he is remembered today. His own nation, the Iranians, have regarded him as "The Father", the very title that had been used during the time of Cyrus himself, by the many nations that he conquered, as according to Xenophon:[101]

And those who were subject to him, he treated with esteem and regard, as if they were his own children, while his subjects themselves respected Cyrus as their "Father" ... What other man but 'Cyrus', after having overturned an empire, ever died with the title of "The Father" from the people whom he had brought under his power? For it is plain fact that this is a name for one that bestows, rather than for one that takes away!

The Babylonians regarded him as "The Liberator", as they were offended by their previous ruler, Nabonidus, for committing sacrilege.[102]

The Book of Ezra narrates a story of the first return of exiles in the first year of Cyrus, in which Cyrus proclaims: "All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD, the God of heaven, given me; and He hath charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah."(Ezra 1:2)

Cyrus was distinguished equally as a statesman and as a soldier. Due in part to the political infrastructure he created, the Achaemenid Empire endured long after his death.[citation needed]

The rise of Persia under Cyrus's rule had a profound impact on the course of world history. Iranian philosophy, literature and religion all played dominant roles in world events for the next millennium. Despite the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century AD by the Islamic Caliphate, Persia continued to exercise enormous influence in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, and was particularly instrumental in the growth and expansion of Islam.[citation needed]

Many of the Iranian dynasties following the Achaemenid Empire and their kings saw themselves as the heirs to Cyrus the Great and have claimed to continue the line begun by Cyrus.[103][104] However, there are different opinions among scholars whether this is also the case for the Sassanid Dynasty.[105]

Alexander the Great was himself infatuated with and admired Cyrus the Great, from an early age reading Xenophon's Cyropaedia, which described Cyrus's heroism in battle and governance and his abilities as a king and a legislator.[96] During his visit to Pasargadae he ordered Aristobulus to decorate the interior of the sepulchral chamber of Cyrus's tomb.[96]

Cyrus's legacy has been felt even as far away as Iceland[106] and colonial America. Many of the thinkers and rulers of Classical Antiquity as well as the Renaissance and Enlightenment era,[107] and the forefathers of the United States of America sought inspiration from Cyrus the Great through works such as Cyropaedia. Thomas Jefferson, for example, owned two copies of Cyropaedia, one with parallel Greek and Latin translations on facing pages showing substantial Jefferson markings that signify the amount of influence the book has had on drafting the United States Declaration of Independence.[108][109][110]

According to Professor Richard Nelson Frye, Cyrus—whose abilities as conqueror and administrator Frye says are attested by the longevity and vigor of the Achaemenid Empire—held an almost mythic role among the Persian people "similar to that of Romulus and Remus in Rome or Moses for the Israelites", with a story that "follows in many details the stories of hero and conquerors from elsewhere in the ancient world."[111] Frye writes, "He became the epitome of the great qualities expected of a ruler in antiquity, and he assumed heroic features as a conqueror who was tolerant and magnanimous as well as brave and daring. His personality as seen by the Greeks influenced them and Alexander the Great, and, as the tradition was transmitted by the Romans, may be considered to influence our thinking even now."[111]

His rule was studied and admired by many of the great leaders, such as Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar and Thomas Jefferson.[112]

Religion and philosophy[edit]

Pierre Briant wrote that given the poor information we have, "it seems quite reckless to try to reconstruct what the religion of Cyrus might have been."[113] It is also debated whether he was a practitioner of Zoroastrianism or whether Zoroastrianism only becomes involved with the imperial religion of the Achaemenid empire after him. The evidence in favor of it comes from some of the names of members of Cyrus' family, and similarities between the description of Cyrus in Isaiah 40–48 and the Gathas.[114] Against the thesis is how Cyrus treated local polytheistic cults, acknowledging their gods and providing funding for the establishment of their temples and other holy sites, as well as a possible late-date for the activity of the Iranian prophet Zoroaster, who founded Zoroastrianism.[115]

The policies of Cyrus with respect to treatment of minority religions are documented in many historical accounts, particularly Babylonian texts and Jewish sources.[116] Cyrus had a general policy of religious tolerance throughout his vast empire. Whether this was a new policy or the continuation of policies followed by the Babylonians and Assyrians (as Lester Grabbe maintains)[117] is disputed. He brought peace to the Babylonians and is said to have kept his army away from the temples and restored the statues of the Babylonian gods to their sanctuaries.[9]

The Cyrus Cylinder was composed in the name of Cyrus with him as the first-person speaker. The Cylinder is highly religious and is framed around the interventions of the god Marduk. It is Marduk who is praised in the outset of the text, whose direct intervention is thought to be responsible for what happened in recent history, and it is Marduk who summons Cyrus for the purpose of righting the wrongs of his predecessor, Nabonidus.[118] Furthermore, Cyrus offers respect not only to the cult of Marduk but also to local cults.[119] Information about religion and ritual during the reign of Cyrus is also available from the Cyropaedia of Xenophon, the Histories of Herodotus, and inscriptions, though these were written in later periods and so must be used carefully. Reliable information may come from the funerary customs around the tomb of Cyrus which indicates a privileged cult honoring Mithra.[120]

Jewish texts[edit]

The treatment of the Jews by Cyrus during their exile in Babylon after Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Jerusalem is reported in the Bible. Cyrus is represented positively and as an agent of Yahweh, even though he is said to "not know" Yahweh (Isaiah 45:4–5).[121]

The Jewish Bible's Ketuvim ends in Second Chronicles with the decree of Cyrus, which returned the exiles to the Promised Land from Babylon along with a commission to rebuild the temple.[122]

Thus saith Cyrus, king of Persia: All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD, the God of heaven given me; and He hath charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whosoever there is among you of all His people – the LORD, his God, be with him – let him go there. — (2 Chronicles 36:23)

This edict is also fully reproduced in the Book of Ezra.

In the first year of King Cyrus, Cyrus the king issued a decree: "Concerning the house of God at Jerusalem, let the temple, the place where sacrifices are offered, be rebuilt and let its foundations be retained, its height being 60 cubits and its width 60 cubits; with three layers of huge stones and one layer of timbers. And let the cost be paid from the royal treasury. Also let the gold and silver utensils of the house of God, which Nebuchadnezzar took from the temple in Jerusalem and brought to Babylon, be returned and brought to their places in the temple in Jerusalem; and you shall put them in the house of God." — (Ezra 6:3–5)

The Jews honored him as a dignified and righteous king. In one Biblical passage, Isaiah refers to him as Messiah (lit. "His anointed one") (Isaiah 45:1), making him the only gentile to be so referred. Elsewhere in Isaiah, God is described as saying, "I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free, but not for a price or reward, says God Almighty." (Isaiah 45:13) As the text suggests, Cyrus did ultimately release the nation of Israel from its exile without compensation or tribute. These particular passages (Isaiah 40–55, often referred to as Deutero-Isaiah) are believed by most modern critical scholars to have been added by another author toward the end of the Babylonian exile (c. 536 BC).[123]

Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, relates the traditional view of the Jews regarding the prediction of Cyrus in Isaiah in his Antiquities of the Jews, book 11, chapter 1:[124]

In the first year of the reign of Cyrus, which was the seventieth from the day that our people were removed out of their own land into Babylon, God commiserated the captivity and calamity of these poor people, according as he had foretold to them by Jeremiah the prophet, before the destruction of the city, that after they had served Nebuchadnezzar and his posterity, and after they had undergone that servitude seventy years, he would restore them again to the land of their fathers, and they should build their temple, and enjoy their ancient prosperity. And these things God did afford them; for he stirred up the mind of Cyrus, and made him write this throughout all Asia: "Thus saith Cyrus the king: Since God Almighty hath appointed me to be king of the habitable earth, I believe that he is that God which the nation of the Israelites worship; for indeed he foretold my name by the prophets, and that I should build him a house at Jerusalem, in the country of Judea." This was known to Cyrus by his reading the book which Isaiah left behind him of his prophecies; for this prophet said that God had spoken thus to him in a secret vision: "My will is, that Cyrus, whom I have appointed to be king over many and great nations, send back my people to their own land, and build my temple." This was foretold by Isaiah one hundred and forty years before the temple was demolished. Accordingly, when Cyrus read this, and admired the Divine power, an earnest desire and ambition seized upon him to fulfill what was so written; so he called for the most eminent Jews that were in Babylon, and said to them, that he gave them leave to go back to their own country, and to rebuild their city Jerusalem, and the temple of God, for that he would be their assistant, and that he would write to the rulers and governors that were in the neighborhood of their country of Judea, that they should contribute to them gold and silver for the building of the temple, and besides that, beasts for their sacrifices.

While Cyrus is praised in the Tanakh (Isaiah 45:1–6 and Ezra 1:1–11), there was Jewish criticism of him after he was lied to by the Cuthites, who wanted to halt the building of the Second Temple. They accused the Jews of conspiring to rebel, so Cyrus in turn stopped the construction, which would not be completed until 515 BC, during the reign of Darius I.[125][126]

According to the Bible, it was King Artaxerxes who was convinced to stop the construction of the temple in Jerusalem. (Ezra 4:7–24)

The historical nature of this decree has been challenged. Professor Lester L Grabbe argues that there was no decree but that there was a policy that allowed exiles to return to their homelands and rebuild their temples. He also argues that the archaeology suggests that the return was a "trickle", taking place over perhaps decades, resulting in a maximum population of perhaps 30,000.[127] Philip R. Davies called the authenticity of the decree "dubious", citing Grabbe and adding that arguing against "the authenticity of Ezra 1.1–4 is J. Briend, in a paper given at the Institut Catholique de Paris on 15 December 1993, who denies that it resembles the form of an official document but reflects rather biblical prophetic idiom."[128] Mary Joan Winn Leith believes that the decree in Ezra might be authentic and along with the Cylinder that Cyrus, like earlier rulers, was through these decrees trying to gain support from those who might be strategically important, particularly those close to Egypt which he wished to conquer. She also wrote that "appeals to Marduk in the cylinder and to Yahweh in the biblical decree demonstrate the Persian tendency to co-opt local religious and political traditions in the interest of imperial control."[129]

Some modern Muslims have suggested that the Quranic figure of Dhu al-Qarnayn is a representation of Cyrus the Great, but the scholarly consensus is that he is a development of legends concerning Alexander the Great.[130]

Politics and management[edit]

Cyrus founded the empire as a multi-state empire governed by four capital states; Pasargadae, Babylon, Susa and Ecbatana. He allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in each state, in the form of a satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A 'satrap' (governor) was the vassal king, who administered the region, a 'general' supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a 'state secretary' kept the official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the satrap as well as the central government.[citation needed]

During his reign, Cyrus maintained control over a vast region of conquered kingdoms, achieved through retaining and expanding the satrapies. Further organization of newly conquered territories into provinces ruled by satraps was continued by Cyrus's successor, Darius the Great. Cyrus's empire was based on tribute and conscripts from the many parts of his realm.[131]

Through his military savvy, Cyrus created an organized army including the Immortals unit, consisting of 10,000 highly trained soldiers.[132] He also formed an innovative postal system throughout the empire, based on several relay stations called Chapar Khaneh.[133]

Cyrus's conquests began a new era in the age of empire building, where a vast superstate, comprising many dozens of countries, races, religions, and languages, were ruled under a single administration headed by a central government. This system lasted for centuries, and was retained both by the invading Seleucid dynasty during their control of Persia, and later Iranian dynasties including the Parthians and Sasanians.[134]

Cyrus has been known for his innovations in building projects; he further developed the technologies that he found in the conquered cultures and applied them in building the palaces of Pasargadae. He was also famous for his love of gardens; the recent excavations in his capital city has revealed the existence of the Pasargadae Persian Garden and a network of irrigation canals. Pasargadae was a place for two magnificent palaces surrounded by a majestic royal park and vast formal gardens; among them was the four-quartered wall gardens of "Paradisia" with over 1000 meters of channels made out of carved limestone, designed to fill small basins at every 16 meters and water various types of wild and domestic flora. The design and concept of Paradisia were exceptional and have been used as a model for many ancient and modern parks, ever since.[135]

The English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne penned a discourse entitled The Garden of Cyrus in 1658 in which Cyrus is depicted as an archetypal "wise ruler" – while the Protectorate of Cromwell ruled Britain.[citation needed]

"Cyrus the elder brought up in Woods and Mountains, when time and power enabled, pursued the dictate of his education, and brought the treasures of the field into rule and circumscription. So nobly beautifying the hanging Gardens of Babylon, that he was also thought to be the author thereof."[citation needed]

Cyrus's standard, described as a golden eagle mounted upon a "lofty shaft", remained the official banner of the Achaemenids.[136]

Cyrus Cylinder[edit]

One of the few surviving sources of information that can be dated directly to Cyrus's time is the Cyrus Cylinder (Persian: استوانه کوروش), a document in the form of a clay cylinder inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform. It had been placed in the foundations of the Esagila (the temple of Marduk in Babylon) as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest in 539 BC. It was discovered in 1879 and is kept today in the British Museum in London.[137]

The text of the cylinder denounces the deposed Babylonian king Nabonidus as impious and portrays Cyrus as pleasing to the chief god Marduk. It describes how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples and restored temples and cult sanctuaries.[138] Although not mentioned specifically in the text, the repatriation of the Jews from their "Babylonian captivity" has been interpreted as part of this general policy.[139]

In the 1970s, the Shah of Iran adopted the Cyrus cylinder as a political symbol, using it "as a central image in his celebration of 2500 years of Iranian monarchy",[140] and asserting that it was "the first human rights charter in history".[141] This view has been disputed by some as "rather anachronistic" and tendentious,[142] as the modern concept of human rights would have been quite alien to Cyrus's contemporaries and is not mentioned by the cylinder.[143][144] The cylinder has, nonetheless, become seen as part of Iran's cultural identity.[140]

The United Nations has declared the relic to be an "ancient declaration of human rights" since 1971, approved by then Secretary General Sithu U Thant, after he "was given a replica by the sister of the Shah of Iran".[145] The British Museum describes the cylinder as "an instrument of ancient Mesopotamian propaganda" that "reflects a long tradition in Mesopotamia where, from as early as the third millennium BC, kings began their reigns with declarations of reforms."[76] The cylinder emphasizes Cyrus's continuity with previous Babylonian rulers, asserting his virtue as a traditional Babylonian king while denigrating his predecessor.[146]

Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum, has stated that the cylinder was "the first attempt we know about running a society, a state with different nationalities and faiths – a new kind of statecraft."[147] He explained that "It has even been described as the first declaration of human rights, and while this was never the intention of the document – the modern concept of human rights scarcely existed in the ancient world – it has come to embody the hopes and aspirations of many."[148]

Currency denomination[edit]

The use of the name Kuruş as a currency denomination for coinage goes back to the 6th century BC, dating to the time of the Croeseid, the world's first gold coin, originally minted by King Croesus of Lydia. The Croeseid was later continued to be minted and spread in a wide geographical area by Cyrus the Great (Old Persian: 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 Kūruš), the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, who defeated King Croesus and conquered Lydia with the Battle of Thymbra in 547 BC. Cyrus (Kūruš) made the Croeseid the standard gold coin of his vast empire, using the same lion and bull design, but with a reduced weight (8.06 grams, instead of the standard 10.7 grams of the original version issued by King Croesus) due to the need for larger amounts of these coins, for a much larger population.

Titles[edit]

His regal titles in full were The Great King, King of Persia, King of Anshan, King of Media, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad, and King of the Four Corners of the World. The Nabonidus Chronicle notes the change in his title from "King of Anshan" to "King of Persia". Assyriologist François Vallat wrote that "When Astyages marched against Cyrus, Cyrus is called 'King of Anshan", but when Cyrus crosses the Tigris on his way to Lydia, he is 'King of Persia.' The coup therefore took place between these two events."[150]

Family tree[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also[edit]

- 2016 Cyrus the Great Revolt

- Kay Bahman

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- List of people known as the Great

Notes[edit]

- ^ Image:

- ^ Cyrus's date of death can be deduced from the last two references to his own reign (a tablet from Borsippa dated to 12 August and the final from Babylon 12 September 530 BC) and the first reference to the reign of his son Cambyses (a tablet from Babylon dated to 31 August and or 4 September), but an undocumented tablet from the city of Kish dates the last official reign of Cyrus to 4 December 530 BC; see R.A. Parker and W.H. Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology 626 B.C. – A.D. 75, 1971.

- ^ Kuraš is also attested as an Elamite name before Cyrus's lifetime.[21]

References[edit]

- ^ Curzon, George Nathaniel (2018). Persia and the Persian Question. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-108-08085-9. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Ilya Gershevitch, ed. (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran: The Median and Achaemenian periods. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Dandamayev 1993, pp. 516–521.

- ^ Xenophon, Anabasis I. IX; see also M. A. Dandamaev "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b c d e f Schmitt (1983) Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty)

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History IV Chapter 3c. p. 170. The quote is from the Greek historian Herodotus.

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. p. 63.

- ^ Bassett, Sherylee R. (1999). "The Death of Cyrus the Younger". The Classical Quarterly. 49 (2): 473–483. doi:10.1093/cq/49.2.473. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 639872. PMID 16437854.

- ^ a b Dandamayev Cyrus (iii. Cyrus the Great) Cyrus's religious policies.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. IV p. 42. See also: G. Buchaman Gray and D. Litt, The foundation and extension of the Persian empire, Chapter I in The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. IV, 2nd edition, published by The University Press, 1927. p. 15. Excerpt: The administration of the empire through satrap, and much more belonging to the form or spirit of the government, was the work of Cyrus ...

- ^ Jona Lendering (2012). "Messiah – Roots of the concept: From Josiah to Cyrus". livius.org. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ The Biblical Archaeology Society (BAS) (24 August 2015). "Cyrus the Messiah". bib-arch.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Margaret Christina Miller (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-521-60758-2. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis; Sarah Stewart (2005). Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B. Tauris. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84511-062-8. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2020.[verification needed]

- ^ Amelie Kuhrt (3 December 2007). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-134-07634-5. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Shabnam J. Holliday (2011). Defining Iran: Politics of Resistance. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-4094-0524-5. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Llewellyn-Jones 2017, p. 67.

- ^ Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Cyrus (name)". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ a b Schmitt 2010, p. 515.

- ^ ; Plutarch, Artaxerxes 1. 3 classics.mit.edu Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine; Photius, Epitome of Ctesias' Persica 52 livius.org Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Tavernier, Jan (2007). Iranica in the Achaemenid Period (ca. 550-330 B.C.). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 528–9. ISBN 9789042918337. OCLC 167407632.

- ^ (Dandamaev 1989, p. 71)

- ^ Tait 1846, p. 342-343.

- ^ Al-Biruni (1879) [1000]. The Chronology of Ancient Nations. Translated by Sachau, C. Edward. p. 152.

- ^ D.T.Potts, Birth of the Persian Empire, Vol. I, ed. Curtis & Stewart, I.B.Tauris-British Museum, London, ç2005, p.13-22

- ^ a b c Waters 2014, p. 171.

- ^ Eric G. L. Pinzelli (2022). Masters of Warfare Fifty Underrated Military Commanders from Classical Antiquity to the Cold War. Pen and Sword Military. p. 3. ISBN 9781399070157.

- ^ The Modern Review Volume 89. the University of Michigan. 1951.

which should really be "Kurush", an Indo-aryan name (cf. "Kuru" of the Mahabharata legend). Thus Cambyses was really "Kambujiya"

- ^ Max Mallowan p. 392. and p. 417

- ^ Kuhrt 2013, p. 177.

- ^ Stronach, David (2003). "HERZFELD, ERNST ii. HERZFELD AND PASARGADAE". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ (Schmitt 1983) under i. The clan and dynasty.

- ^ e. g. Cyrus Cylinder Fragment A. ¶ 21.

- ^ Schmitt, R. "Iranian Personal Names i.-Pre-Islamic Names". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 4.

Naming the grandson after the grandfather was a common practice among Iranians.

- ^ Visual representation of the divine and the numinous in early Achaemenid Iran: old problems, new directions; Mark A. Garrison, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas; last revision: 3 March 2009, see page: 11 Archived 26 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Briant 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Waters 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Dandamev, M. A. (1990). "Cambyses". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. ISBN 0-7100-9132-X. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ (Dandamaev 1989, p. 9)

- ^ Waters 2004, p. 97.

- ^ "Pasargadae, Palace P - Livius". www.livius.org. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Amélie Kuhrt, The Ancient Near East: c. 3000–330 BC, Routledge Publishers, 1995, p.661, ISBN 0-415-16762-0

- ^ Benjamin G. Kohl; Ronald G. Witt; Elizabeth B. Welles (1978). The Earthly republic: Italian humanists on government and society. Manchester University Press ND. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7190-0734-7. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Kuhrt 2013, p. 106.

- ^ Grayson 1975, p. 111.

- ^ Herodotus, p. 1.95.

- ^ Herodotus, p. 1.107-21.

- ^ Stories of the East From Herodotus, pp. 79–80

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Briant 2002, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Antoine Simonin. (8 Jan 2012). "Sogdiana Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Kirill Nourzhanov, Christian Bleuer (2013), Tajikistan: a Political and Social History, Canberra: Australian National University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-1-925021-15-8.

- ^ Jack Martin Balcer (1984). Sparda by the bitter sea: imperial interaction in western Anatolia. Scholars Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-89130-657-3. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ A. Sh. Sahbazi, "Arsama", in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 21 edited by Hugh Chrisholm, b1911, pp. 206–07

- ^ Rollinger, Robert, "The Median "Empire", the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 B.C. Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine"; Lendering, Jona, "The End of Lydia: 547? Archived 6 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ a b Herodotus, The Histories, Book I Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 440 BC. Translated by George Rawlinson.

- ^ Croesus Archived 30 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine: Fifth and last king of the Mermnad dynasty.

- ^ "Syria - Urartu 612-501".

- ^ The life and travels of Herodotus, Volume 2, by James Talboys Wheeler, 1855, pp. 271–74

- ^ Herodotus, A. Barguet. L'Enquête (in French). Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. pp. 111–124.

- ^ Ancient India, by Vidya Dhar Mahajan, 2019, pp. 203

- ^ Chronology of the Ancient World, by H. E. L. Mellersh, 1994

- ^ Tavernier, Jan. "Some Thoughts in Neo-Elamite Chronology" (PDF). p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ^ Kuhrt, Amélie. "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes", in The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV – Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, pp. 112–38. Ed. John Boardman. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-521-22804-2

- ^ Nabonidus Chronicle, 14 Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tolini, Gauthier, Quelques éléments concernant la prise de Babylone par Cyrus, Paris. "Il est probable que des négociations s'engagèrent alors entre Cyrus et les chefs de l'armée babylonienne pour obtenir une reddition sans recourir à l'affrontement armé." p. 10 Archived 8 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- ^ Bealieu, Paul-Alain (1989). The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 536–539 B.C. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 230. ISBN 0-300-04314-7.

- ^ The date depends on when exactly the lunar month was deemed to have begun.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Nabonidus Chronicle, 15–16 Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Potts, Daniel (1996). Mesopotamian civilization: the material foundations. Cornell University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-8014-3339-9. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Bealieu, Paul-Alain (1989). The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 536–539 B.C. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-300-04314-7.

- ^ Nabonidus Chronicle, 18 Archived 26 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Briant 2002, pp. 44–49.

- ^ a b "British Museum Website, The Cyrus Cylinder". Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Kuhrt 1995, p. 647.

- ^ A history of Greece, Volume 2, By Connop Thirlwall, Longmans, 1836, p. 174

- ^ a b "Ancient History Sourcebook: Herodotus: Queen Tomyris of the Massagetai and the Defeat of the Persians under Cyrus". Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T. (2012). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-107-01652-1. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Tomyris, Queen of the Massagetae, Defeats Cyrus the Great in Battle Archived 29 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Herodotus, The Histories

- ^ Nino Luraghi (2001). The historian's craft in the age of Herodotus. Oxford University Press US. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-924050-0. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ a b Ilya Gershevitch, ed. (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran: The Median and Achaemenian periods, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–98. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Michael the Syrian. Chronicle of Michael the Great, Patriarch of the Syrians – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Xenophon, Cyropaedia VII. 7; M.A. Dandamaev, "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, p. 250. See also H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg "Cyropaedia Archived 17 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, on the reliability of Xenophon's account.

- ^ A political history of the Achaemenid empire, By M.A. Dandamaev, Brill, 1989, p. 67.

- ^ a b UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2006). "Pasargadae". Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 15.3.7; Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri 6.29

- ^ Life of Alexander, 69, in Plutarch: The Age of Alexander, translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert (Penguin Classics, 1973), p. 326.; similar inscriptions give Arrian and Strabo.

- ^ Cyrus's date of death can be deduced from the last reference to his own reign (a tablet from Borsippa dated to 12 Augustus 530) and the first reference to the reign of his son Cambyses (a tablet from Babylon dated to 31 August); see R.A. Parker and W.H. Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology 626 B.C. – A.D. 75, 1971.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. "Behistun Inscription". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e ((grk.) Lucius Flavius Arrianus), (en.) Arrian (trans.), Charles Dexter Cleveland (1861). A compendium of classical literature:comprising choice extracts translated from Greek and Roman writers, with biographical sketches. Biddle. p. 313. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson (1906). Persia past and present. The Macmillan Company. p. 278.

tomb of cyrus the great.

- ^ Ralph Griffiths; George Edward Griffiths (1816). The Monthly review. 1816. p. 509.

Cyrus influence on persian identity.

- ^ a b c Ulrich Wilcken (1967). Alexander the Great. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-393-00381-9.

Alexander admiration of cyrus.

- ^ John Maxwell O'Brien (1994). Alexander the Great: the invisible enemy. Psychology Press. pp. 100–01. ISBN 978-0-415-10617-7. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ James D. Cockcroft (1989). Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55546-847-7.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the Cyrus legacy.

- ^ Freeman 1999: p. 188

- ^ "The Cyrus cylinder: Diplomatic whirl". The Economist. 23 March 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Xenophon (1855). The Cyropaedia. H.G. Bohn.

cyropaedia.

- ^ Cardascia, G., Babylon under Achaemenids, in Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye (1963). The Heritage of Persia. World Pub. Co.

- ^ Cyrus Kadivar (25 January 2002). "We are Awake". The Iranian.

- ^ E. Yarshater, for example, rejects that Sassanids remembered Cyrus, whereas R.N. Frye do propose remembrance and line of continuity: See A. Sh. Shahbazi, Early Sassanians' Claim to Achaemenid Heritage, Namey-e Iran-e Bastan, Vol. 1, No. 1 pp. 61–73; M. Boyce, "The Religion of Cyrus the Great" in A. Kuhrt and H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, eds., Achaemenid History III. Method and Theory, Leiden, 1988, p. 30; and The History of Ancient Iran, by Frye p. 371; and the debates in Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, et al. The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Persia: New Light on the Parthian and Sasanian Empires, Published by I. B. Tauris in association with the British Institute of Persian Studies, 1998, ISBN 1-86064-045-1, pp. 1–8, 38–51.

- ^ Jakob Jonson: "Cyrus the Great in Icelandic epic: A literary study". Acta Iranica. 1974: 49–50

- ^ Nadon, Christopher (2001), Xenophon's Prince: Republic and Empire in the Cyropaedia, Berkeley: UC Press, ISBN 0-520-22404-3

- ^ "Cyrus and Jefferson: Did they speak the same language?". www.payvand.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Cyrus Cylinder: How a Persian monarch inspired Jefferson". BBC News. 11 March 2013. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Boyd, Julian P. "The Papers of Thomas Jefferson". Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Cyrus II Encyclopædia Britannica 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online". Original.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 December 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cyrus the Great Biography |". Biography Online. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (2014). "Achaemenid Religion". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ^ Shannon, Avram (2007). "The Achaemenid Kings and the Worship of Ahura Mazda: Proto-Zoroastrianism in the Persian Empire". Studia Antiqua. 5 (2): 79–85.

- ^ Crompton, Samuel Willard (2008). Cyrus the Great. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7910-9636-9.

- ^ Oded Lipschitz; Manfred Oeming, eds. (2006). "The "Persian Documents" in the Book of Ezra: Are They Authentic?". Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period. Eisenbrauns. p. 542. ISBN 978-1-57506-104-7.

- ^ Finkel 2013, p. 23–24.

- ^ Finkel 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Briant 2002, p. 93–96.

- ^ Lind, Millard (1990). Monotheism, power, justice: collected Old Testament essays. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-936273-16-7.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 2 Chronicles 36 - New Living Translation". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ Simon John De Vries: From old Revelation to new: a tradition-historical and redaction-critical study of temporal transitions in prophetic prediction Archived 8 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing 1995, ISBN 978-0-8028-0683-3, p. 126

- ^ Josephus, Flavius. The Antiquities of the Jews, Book 11, Chapter 1 [1] Archived 20 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Goldwurm, Hersh (1982). History of the Jewish People: The Second Temple Era. ArtScroll. pp. 26, 29. ISBN 0-89906-454-X.

- ^ Schiffman, Lawrence (1991). From text to tradition: a history of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing. pp. 35, 36. ISBN 978-0-88125-372-6.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud: A History of the Persian Province of Judah v. 1. T & T Clark. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-567-08998-4. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Philip R. Davies (1995). John D Davies (ed.). Words Remembered, Texts Renewed: Essays in Honour of John F.A. Sawyer. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-85075-542-5. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Winn Leith, Mary Joan (2001) [1998]. "Israel among the Nations: The Persian Period". In Michael David Coogan (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World (Google Books). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-19-513937-2. LCCN 98016042. OCLC 44650958. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ Toorawa 2011, p. 8.

- ^ John Curtis; Julian Reade; Dominique Collon (1995). Art and empire. The Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1140-7. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Pierre Briant

- ^ Herodotus, Herodotus, trans. A.D. Godley, vol. 4, book 8, verse 98, pp. 96–97 (1924).

- ^ Wilcox, Peter; MacBride, Angus (1986). Rome's Enemies: Parthians And Sassanid Persians. Osprey Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 0-85045-688-6.

- ^ Persepolis Recreated, Publisher: NEJ International Pictures; 1ST edition (2005) ISBN 978-964-06-4525-3

- ^ Alireza Shapur Shahbazi (15 December 1994), "DERAFŠ" Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 3, pp. 312–315.

- ^ H.F. Vos, "Archaeology of Mesopotamia", p. 267 in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. ISBN 0-8028-3781-6

- ^ "The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures". Vol. 1. Ed. James B. Pritchard. Princeton University Press, 1973.

- ^ "British Museum: Cyrus Cylinder". British Museum. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ a b British Museum explanatory notes, "Cyrus Cylinder": In Iran, the cylinder has appeared on coins, banknotes and stamps. Despite being a Babylonian document it has become part of Iran's cultural identity."

- ^ Neil MacGregor, "The whole world in our hands", in Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice, pp. 383–84, ed. Barbara T. Hoffman. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-85764-3

- ^ Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran, p. 39. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30731-8 (restricted online copy, p. 39, at Google Books)

- ^ John Curtis, Nigel Tallis, Beatrice Andre-Salvini. Forgotten Empire, p. 59. University of California Press, 2005. (restricted online copy, p. 59, at Google Books)

- ^ See also Amélie Kuhrt, "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes", in The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV – Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, p. 124. Ed. John Boardman. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-521-22804-2

- ^ The telegraph (16 July 2008). "Cyrus Cylinder". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Hekster, Olivier; Fowler, Richard (2005). Imaginary kings: royal images in the ancient Near East, Greece and Rome. Vol. Oriens et occidens 11. Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-515-08765-0.

- ^ Barbara Slavin (6 March 2013). "Cyrus Cylinder a Reminder of Persian Legacy of Tolerance". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (24 February 2013). "A 2,600-year-old icon of freedom comes to the United States". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Classical Numismatic Group

- ^ François Vallat (2013). Perrot, Jean (ed.). The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. I.B.Tauris. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-84885-621-9. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "Family Tree of Darius the Great" (JPG). Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

Bibliography[edit]

Ancient sources[edit]

- The Nabonidus Chronicle of the Babylonian Chronicles

- The Verse account of Nabonidus

- The Prayer of Nabonidus (one of the Dead Sea scrolls)

- The Cyrus Cylinder

- Herodotus (The Histories)

- Ctesias (Persica)

- The biblical books of Isaiah, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah

- Flavius Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews)

- Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War)

- Plato (Laws (dialogue))

- Xenophon (Cyropaedia)

- Quintus Curtius Rufus (Library of World History)

- Plutarch (Plutarch's Lives)

- Fragments of Nicolaus of Damascus

- Arrian (Anabasis Alexandri)

- Polyaenus (Stratagems in War)

- Justin (Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine) (in English)

- Polybius (The Histories (Polybius))

- Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica)

- Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae)

- Strabo (History)

- Quran (Dhul-Qarnayn, Al-Kahf)

Modern sources[edit]

- Boardman, John, ed. (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History IV: Persia, Greece, and the Western Mediterranean, C. 525–479 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22804-2.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1–1196. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Cardascia, G (1988). "Babylon under Achaemenids". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 3. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-939214-78-4. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Church, Alfred J. (1881). Stories of the East From Herodotus. London: Seeley, Jackson & Halliday.

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A political history of the Achaemenid empire. Leiden: Brill. p. 373. ISBN 90-04-09172-6.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (1993). "Cyrus iii. Cyrus II The Great". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 516–521. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- Finkel, Irving (2013). The Cyrus Cylinder: The Great Persian Edict from Babylon. I.B. Tauris.

- Freeman, Charles (1999). The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-7139-9224-7.

- Frye, Richard N. (1962). The Heritage of Persia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 1-56859-008-3

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran: Vol. 2; The Median and Achaemenian periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20091-1.

- Grayson (1975), Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). "13". The Ancient Near East: c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge. p. 647. ISBN 0-415-16763-9.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (2013). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-01694-3. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2017). "The Achaemenid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BC - 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0-692-86440-1. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Moorey, P.R.S. (1991). The Biblical Lands, VI. New York: Peter Bedrick Books . ISBN 0-87226-247-2

- Olmstead, A. T. (1948). History of the Persian Empire [Achaemenid Period]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-62777-2

- Palou, Christine; Palou, Jean (1962). La Perse Antique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1983). "Achaemenid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 3. London: Routledge. Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2010). CYRUS i. The Name. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Tait, Wakefield (1846). The Presbyterian review and religious journal. Oxford University. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Toorawa, Shawkat M. (2011). "Islam". In Allen, Roger (ed.). Islam; A Short Guide for the Faithful. Eerdmans. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8028-6600-4. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Waters, Matt (2004). "Cyrus and the Achaemenids". Iran. 42. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 91–102. doi:10.2307/4300665. JSTOR 4300665. (registration required)

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–272. ISBN 978-1-107-65272-9. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Ball, Charles James (1899). Light from the East: Or the witness of the monuments. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Beckman, Daniel (2018). "The Many Deaths of Cyrus the Great". Iranian Studies. 51 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/00210862.2017.1337503. S2CID 164674586.

- Bengtson, Hermann. The Greeks and The Persians: From the Sixth Century to the Fourth Century. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969.

- Bickermann, Elias J. (September 1946). "The Edict of Cyrus in Ezra 1". Journal of Biblical Literature. 65 (3): 249–75. doi:10.2307/3262665. JSTOR 3262665.

- Cannadine, David; Price, Simon (1987). Rituals of royalty : power and ceremonial in traditional societies (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33513-2.