The Wave (2008 film)

| The Wave | |

|---|---|

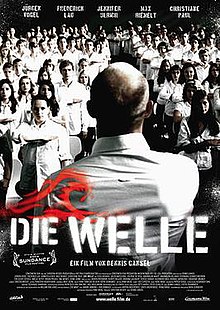

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Dennis Gansel |

| Screenplay by | Dennis Gansel Peter Thorwarth |

| Based on | "The Third Wave" (recount of the original Third Wave experiment)[1] by Ron Jones The Wave by Todd Strasser |

| Produced by | Rat Pack Filmproduktion Christian Becker |

| Starring | Jürgen Vogel Frederick Lau Max Riemelt Jennifer Ulrich |

| Music by | Heiko Maile |

| Distributed by | Constantin Film Verleih |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Budget | €5 million [citation needed] |

| Box office | €32,350,637[2] |

The Wave (German: Die Welle) is a 2008 German socio-political thriller film directed by Dennis Gansel and starring Jürgen Vogel, Frederick Lau, Jennifer Ulrich and Max Riemelt in the leads. It is based on Ron Jones' social experiment The Third Wave and Todd Strasser's novel The Wave. The film was produced by Christian Becker for Rat Pack Filmproduktion. The movie was successful in German cinemas, and 2.3 million people watched it in the first ten weeks after its release.

In the film, a history teacher starts an experiment in manipulation of the masses, while trying to teach his class about autocracy. The students unwittingly start embracing fascism.

Plot[edit]

A history teacher, Rainer Wenger, is forced to teach a class on autocracy, despite being an anarchist and wanting to teach the class on anarchy. When his students, the third generation after the Second World War,[3] do not believe that a dictatorship could be established in modern Germany, he starts an experiment to demonstrate how easily the masses can be manipulated. He begins by demanding that all students address him as "Herr Wenger", as opposed to Rainer,[4] and places students with poor grades beside students with good grades — purportedly so they can learn from one another and become better as a whole. When speaking, they must stand and give short, direct answers. Wenger shows his students the effect of marching together in the same rhythm, motivating them by suggesting that they are superior to the anarchy class, which is below them. Wenger suggests a uniform of a white shirt and jeans, to remove class distinction and further unite the group. A student in the class named Mona argues it will remove individuality, but she is dismissed. Another student in the class named Karo shows up to class without the uniform and is ostracized. The students decide among themselves they need a name, deciding on "Die Welle" (The Wave). Karo suggests another name, but she is the only person in the class who votes for it.

The group is shown to grow closer together, and former bullies Sinan and Bomber are shown to reform, protecting Tim, the class outcast, from a pair of anarchists demanding he sell them drugs. Sinan also creates a distinctive logo for the group, while Bomber creates a salute. Tim becomes very attached to the group, having finally become an accepted member of a social group. He burns all of his brand-name clothes, after a discussion about how large corporations do not take responsibility for their actions. Karo and Mona protest the actions of the group, and Mona, disgusted with how her classmates are embracing fascism, leaves the project group. Her other classmates do not see the connection with fascism and continue attending the class. The members of The Wave begin spray-painting their logo around town at night, having parties where only Wave members are allowed to attend, and ostracizing and tormenting anyone not in their group.

When Tim and his group of new friends are confronted by a group of angry punks (including those that Tim faced previously), Tim pulls a Walther PP pistol, causing them to back down. Tim explains to his shocked friends that the pistol only fires blanks. Tim later shows up at Wenger's house, offering to be his bodyguard. Although he declines his offer, Wenger still invites Tim in for dinner; this puts further strain on his already tense relationship with his wife, Anke, who thinks his experiment has gone too far. Wenger finally asks Tim to leave his house, only to find the next morning that Tim had slept outside on his doorstep. Anke, upset upon learning this, tells Wenger to stop the experiment immediately. Wenger accuses her of being jealous and insults her dependency on pills. Shocked, Anke leaves him, saying the Wave has made him into a terrible person.

Karo continues her opposition to the Wave, earning the anger of many in the group, who ask her boyfriend, Marco, to do something about it. A water polo competition is due to happen later that day, and Wenger asks the Wave to show up in support of the team. Karo and Mona, denied entry to the competition by members of The Wave, sneak in another way in order to distribute anti-Wave fliers. Members of the Wave notice this and scramble to retrieve the papers before anybody reads them. In the chaos, Sinan starts a fight with an opposing team member, with the two almost drowning each other as a result. Members of the Wave in the stands begin to violently shove one another. After the match, Marco confronts Karo and accuses her of causing the fight. She replies that the Wave has brainwashed him completely. He slaps Karo, causing her to get a nosebleed. Unsettled by his own behaviour, Marco approaches Wenger and asks him to stop the project. Wenger seemingly agrees and calls a rally for the Wave members for the following day in the school's auditorium.

Once in the rally, Wenger has the doors locked and begins whipping the students into a fervour. When Marco protests, Wenger calls him a traitor and orders the students to bring him to the stage for punishment. However, Wenger turns out to have been acting and was using this meeting to test the students and to see how extreme the Wave has become. Wenger declares that he is disbanding the Wave, but Dennis argues that they should try to salvage the good parts of the movement. Wenger points out there is no way to remove the negative elements of fascism. Seeing the movement falling apart right in front of his very eyes, Tim suffers a mental breakdown and pulls out a gun, refusing to accept the Wave is over as he does not want to lose all that he's gained. When Bomber says the gun only fires blanks and tries to take it, Tim shoots him, revealing it has live rounds. When Tim asks why he shouldn't shoot Wenger too, Wenger says that without him, there would be no one to lead the Wave and it would just die anyway. Utterly consumed by despair, Tim abruptly shoots himself in the head, preferring to commit suicide than go on living without the movement.

Horrified, Wenger cradles his corpse and looks on at how his actions have resulted in his whole class being scarred for the rest of their lives. The film ends with Wenger being arrested by the police and driven away, Bomber being taken away to the hospital, and Marco and Karo being re-united; the final shot shows Wenger in the back of a police car, staring blankly into the camera, a look of distress on his face.

Cast[edit]

- Jürgen Vogel as Rainer Wenger, the main character and teacher who started the experiment with his class.

- Frederick Lau as Tim, an insecure and mentally unstable boy having problems with his family. At the beginning of the film he is pictured as a drug dealer until The Wave project starts. Then he becomes a committed member and finds new friends.

- Max Riemelt as Marco, a strong boy, who plays in Wenger's water polo team. He is Karo's boyfriend.

- Jennifer Ulrich as Karo, a diligent and intelligent student. She protests against The Wave and because of this, she has intense rows with Marco and her friends.

- Cristina do Rego as Lisa, a shy girl who becomes more self-confident thanks to The Wave. She is best friends with Karo, but later they have an argument when Karo protests against The Wave.

- Christiane Paul as Anke Wenger, the wife of Rainer who teaches in the same school but leaves him after seeing how much damage The Wave is affecting both the school and their students.

- Elyas M'Barek as Sinan, a student of Turkish descent and member of the water-polo team. He is Bomber's best friend. Elyas M'Barek had earlier appeared in Gansel's film Mädchen, Mädchen.

- Maximilian Vollmar as Bomber, a bully who reforms thanks to The Wave and befriends Tim.

- Maximilian Mauff as Kevin, an upper-class student who clashes with The Wave at first until he joins the group for social reasons as he loses his status.

- Jacob Matschenz as Dennis, a student who comes from the GDR. He becomes a member of The Wave, like most of his classmates.

- Ferdinand Schmidt-Modrow as Ferdi

- Tim Oliver Schultz as Jens

- Amelie Kiefer as Mona

- Odine Johne as Maja

- Fabian Preger as Kaschi

- Tino Mewes as Schädel

- Maxwell Richter as Anarchist

- Liv Lisa Fries as Laura

- Alexander Held as Tim's father

- Johanna Gastdorf as Tim's mother

- Dennis Gansel as Martin

- Maren Kroymann as Dr. Kohlhage

Background[edit]

The Wave is not the only movie to convert a social experiment conducted in the United States into a fictionalized plot. The Stanford prison experiment of 1971 was adapted for the 2001 production Das Experiment by Oliver Hirschbiegel, and the 2015 production directed by Kyle Patrick Alvarez, The Stanford Prison Experiment. Gansel's Wave is based on teacher Ron Jones's "Third Wave" experiment, which took place at a Californian school in 1967. Because his students did not understand how something like National Socialism could even happen, he founded a totalitarian, strictly-organized "movement" with harsh punishments that was led by him autocratically. The intricate sense of community led to a wave of enthusiasm not only from his own students, but also from students from other classes who joined the program later. Jones later admitted to having enjoyed having his students as followers. To eliminate the upcoming momentum, Jones aborted the project on the fifth day and showed the students the parallels towards the Nazi youth movements.[5][6]

In 1976, Jones published a narrative based on those experiences titled The Third Wave, which was made into a television movie of the same title in 1981. In the same year, author Todd Strasser, writing under the pen-name "Morton Rhue", published his book "The Wave" (a novelization of the television movie), which was published in Germany in 1984 and has since enjoyed great success as a school literature text. It has sold a total of over 2.5 million copies.[5][6][7] Furthermore, the 1981 movie is available at almost all public media centers.[7][8] The story has also influenced many plays and role plays worldwide.[5][6]

The screenplay is based on an article written by Ron Jones in which he talks about the experiment and how he remembers it. The rights to the story which belonged to Sony were given over to Dennis Gansel for the production of a German movie.[9] As a consequence, Todd Strasser, whose novel popularized the material in Germany, and the publisher Ravensburg, did not receive direct revenues from the film project.[10] Gansel was working on the book for one year until he asked Peter Thorwarth to join him as a co-author. The screenplay moves the experiment, which was carried out in California in the 1960s, to present day Germany. The specific location is never mentioned explicitly as it stands for Germany as a whole.

Gansel explained that he did not intend to reenact Jones’ experiment, but rather show how it would be carried out in present-day Germany. He said the movie is not an adaption and that he changed characters, dialogues as well as the beginning and ending of the movie.[9] This also includes subsidiary aspects such as the football team which was turned into a water polo team in the German version whose coach, as opposed to the original, is the teacher himself. The major difference, however, concerns the physical violence and the bloody end which became part of the movie. Nonetheless, Gansel claimed in an interview that it was extremely important to him to ensure that his movie would not differ as much from the experiment as Strasser's book. Thereby he described Jones, who supported the film project as a counselor, as a "living certificate" of authenticity and that the ending was inspired by the Emsdetten school shooting.[11] He claimed that Jones does not like the way the characters in Strasser's novel are depicted.[12] The former teacher commented that Gansel's movie gave an "incredibly convincing" account of the actual experiment.[6]

According to Gansel, representatives of the Bavarian film-funding agency which were initially inquired to fund the film project declined because they compared it to Strasser's novel. Furthermore, they criticized that the teacher lacked a clear anti-authoritarian position in the submitted script. The entire project was jeopardized and the first film-funding agency to grant financial aid was the Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg. Afterwards, the German Federal Film Board (FFA) and the German Federal Film Fund (DFFF) as well as other co-producers decided to subsidize the project. Constantin Film also became one of the sponsors and further managed the film's distribution. The overall budget of the movie amounts to 4.5 million euros and the movie was shot within 38 days.

Themes and concepts[edit]

Gansel’s concept[edit]

According to Dennis Gansel, German students have grown tired of the topic concerning the Third Reich. Gansel himself had felt an oversaturation during his schooldays and had developed an emotional connection to this chapter of German history only after watching the film Schindler's List.[9] One difference between the experiment conducted at the time in the United States and today's Germany he saw in the fact that the American students had asked themselves quite horrified how there could even exist something like the concentration camps. His film, however, was made on the premise that people felt immune to the possibility of a repetition of history as a result of the intensive study of National Socialism and its mechanisms. “Therein lies the great danger. It is an interesting fact that we always believe that what happens to others would never happen to us. We blame others, for example the less educated or the East Germans, etc. However, in the Third Reich the house caretaker was just as fascinated by the movement as was the intellectual.”[13]

The small town the movie is set in is prosperous and does not show any salient social or economic problems and the teacher practices a liberal lifestyle. Gansel is convinced that the plot gains a broader psychological validity by the choice of such a location. “Everyone thinks they would have been Anne Franks and Sophie Scholls in Nazi Germany. In my opinion this is complete nonsense. I would say that biographies of resistance rather originate in coincidences,” claims Gansel. He then explains that, for example, Karo's political awareness and opposition arise out of vanity: she does not like the white shirt.[14] In the past Gansel had been sure that he would have been part of the resistance but while working on The Wave he realized how “non-politically” the conversion of people took place.[9] He remarks that every human being has the need for belonging to a group.

He says he does not believe that films are capable of having a greater political impact on the viewers and that a film can only influence people who were already sensitized to the topic presented. In his opinion films can at best stimulate discussions, but to be able to do that they have to be really entertaining. “In Germany there has always existed the great misunderstanding that politics in the world of cinema were synonymous with boredom,” says Gansel. He claims that in between high-brow cinema, as films by Christian Petzold, and the entertaining comedies by Til Schweiger there was a vast gap in Germany, which urgently had to be filled.[14] He made the film in a way that should have a “seductive effect” on the viewers to make them interested in The Wave and by doing so show the powerful attraction such a movement can have.[9][14] He chose Jürgen Vogel as the leading actor because he wanted someone he himself would have liked to have as a teacher, for Vogel brought with him real life experience and a certain kind of authority. In Gansel's own schooldays it had been these kind of teachers whom he had trusted the most. Gansel, whose grandfather had been a Wehrmacht officer, also announced that this film would be the first and last one concerning the topic of the Third Reich in his career as a director.[9]

Formal realisation[edit]

Teacher Wenger's casual manner at the beginning of the film contributes to the expectation of a comedy.[15][16] Reviewers have noted a similarity to American films that deal with competent teachers who evoke the capability of disadvantaged students, such as Dead Poets Society[17] or U.S. high school films that assign a particular adolescent type to every character.[10] Gansel focuses less on mental motivation processes of the individual characters but rather on the resulting sense of community.[18] His script co-author Thorwarth emphasized that it is necessary to define the characters very clearly in order to retain the common thread despite the variety. The film is structured by five days of the project week. At this, the beginning of every new day of the week is marked by an insert.[15]

The narrative style doesn't keep the audience at distance, so that it can reflect on the things that happened, but rather lets them experience the occurrences; so the plot is narrated linearly. Similar experiences of various characters, for instance, scenes in which students tell their parents about their day at school, are realized as cross-cutting and thus demonstrate the range of different perceptions of the day. The film is narrated from the perspective of a third person, although particular scenes provide individual characters' subjective points of view. An example for this is the scene in which Karo is in the schoolhouse at night, or the scene at the end when Wenger is arrested by the police and driven away. While on the one hand Wenger is filmed in low angle shot and sings rock music in the opening sequence, on the other hand he seems depressed in this last scene. "Slow motion shots reflect [his] tormenting self-reproaches." The change to the subjective view of the thoughtful character corresponds to the dramatic composition throughout the film. This change is meant to initiate reflections on the part of the audience.[15] Gansel justifies the drastic end with the necessity of shocking the audience after the length of the film, of providing a counter-statement and of taking up a stance.[14] A critic assumed that in this country you can't say Adolf without having consequences. So triggering off fascism involves a couple of dead persons.[17]

Throughout the film high and low angle shots are used in order to express the balance of power, those at the “top” and those at the “bottom”. At some parts, the film utilizes stylistic devices of the Nazi weekly reviews, which recorded Hitler's speeches. An example for this is the closing speech of Wenger. In this scene the camera is placed close behind him, at the level of his nape, and so offers a view of the geometrically arranged crowd of students.[15] Other scenes are based on pop culture. Especially the film clip in which the Wave-supporters spray their logo on buildings, is staged in the style of a music video.[15][19] This logo is designed as "a jagged tsunami wave in a similar way to Manga comics."[19] There is a high frequency and abrupt manner of film editing. There is fast, even rapid camera work and the rock music, that accompanies many of the scenes, is often characterized as impulsive.[7][20][21]

Reception[edit]

German criticism of Die Welle was extremely divided. Solely the opinions on the actors were always the same. “From the first scene on, the sympathetic guy tears the audience on his side”,[19] it was reported about Jürgen Vogel, he was transforming the moral ambiguity of his figure into a “mercurial energy”.[22] He played his role realistically,[20] was “credible”[7] or the ideal cast.[16] For the young actors the most frequently used word was “convincing”,[7][20][23] while the 18-year-old Frederick Lau in his role as the outcast Tim received special highlighting.[19][23] In contrast to the praise for the actors, many critics demurred on the figures, developed by the screenplay. They criticized that the psychological developments are missed out, Wenger and the other figures are partially constructed by cliches,[20] or defined by “something model-like”,[7] they also argued that the figures are “slightly oversubscribed stereotypes”[24] or “placeholders”.[10] According to the lack of depth in their motives and emotions, they seem to be distanced, the critics argued further, especially Karo's transformation from the enthusiastic participant to the aggressive opponent is not comprehensible.[23] The critics don't see a stringent necessity for the students, why they should join the movement at all, because their commitment to conformity is not imaginable in West Germany today. The movie, according to the critics, therefore often seems “very pedagogically prescribing: you know, what is meant, but you don’t really believe it.”[25] The critics add, that the pretended serfdom of the Wave-supporters is also undermined by celebrating and tagging excessively.[23] Why the teacher, established as an authority person, becomes a victim of his own staged role play, “remains puzzling“, the critics claim. Because Gansel attributes a position as a left-winger and former squatter to him, he involuntarily provides further evidence for the Götz Aly's thesis, that the 68er Bewegung have further developed the authoritarian body of thought of the Nazis of 1933, they argued critically.[18] But the character‘s composition was also defended: “The categorization is rather necessary here, because it shows the vulnerability of entirely different people for one and the same idea.“[26]

There was also disagreement about the staging. The movie was exciting, disturbing and fascinating,[21] and deals with a difficult plot as exciting entertainment, some critics pointed out.[27] For a mainstream movie "The Wave“ was often "pleasantly rough and snotty“, they reported.[19] Other critics accused the movie of being conventionally staged, similar to a Tatort-police procedural TV series,[25] or let off steam about the "graffiti-scenes and a nearly never-ending escalating party scene."[23]

Jones was complimentary of the film, praising its accuracy to the real-life events (despite the changed ending) that he felt the television film and Strasser's book missed. He noted that although the ending deviates from what happened, its depiction of a "what-if" scenario for the Wave getting out of the teacher's control was closer to what he felt would happen to a true fascist movement even if its leader renounced it.[28]

Soundtrack[edit]

The soundtrack of the film was released on 25 May 2008 through EMI Germany, and contains tracks by The Subways, Kilians, Johnossi, Digitalism and The Hives, as well as a cover version of the classic Ramones' track "Rock 'n' Roll High School" made for the film by the German punk band EL*KE. Jan Plewka wrote and recorded a song for the film, Was Dich So Verändert Hat, in both a German and English version. The German version ended up in the film but the English version is available on an international version of the soundtrack. The title-song "Garden Of Growing Hearts" was performed by Berlin band Empty Trash. The original film score was composed by Heiko Maile, a member of the band Camouflage.

- "Intro" – Jürgen Vogel & Tim Oliver Schultz

- "Rock'n'Roll Highschool" – EL*KE

- "Rock & Roll Queen" (Album Version) – The Subways

- "Execution Song" – Johnossi

- "Fight The Start" – Kilians

- "Garden Of Growing Hearts" (Radio Edit) – Empty Trash

- "Spending My Time" – Orange But Green

- "Short Life Of Margott" – Kilians

- "Everything Is Under Control" – Coldcut

- "Bored" – Ronda Ray featuring Markie J

- "Homzone" – Digitalism

- "Move It!" – Ronda Ray Featuring Trevor Jackson

- "Nightlite" (feat. Bajka) – Bonobo

- "Was Dich So Verändert Hat" – Jan Plewka

- "Arrested" – Heiko Maile

- "Power Control" – Ronda Ray Featuring Trevor Jackson

- "Climbing Up the Tower" – Heiko Maile

- "Sending Out an SMS" – Heiko Maile

- "Swimming" – Heiko Maile

- "White Shirts" – Heiko Maile

- "Dark School" – Heiko Maile

Differences from the 1981 film[edit]

In the 1981 film and its novelization, the action takes place in the fictitious Gordon High School, which in turn is based on a series of events at a school in Palo Alto, California. The names were changed to sound German, but the characters are similar. For example, Rainer Wenger, Karo, Marco, Mona, and Tim correspond to Ben Ross, Laurie Saunders, David Collins, Andrea, and Robert Billings. The outsider theme was expanded by introducing three new characters: Sinan who is Turkish, Kevin the aggressive bully, and Dennis from East Germany who is mocked as "Ossi". The 1981 film's ending, where there is no violence and the teacher is not arrested, is much tamer than the ending of Die Welle and is more accurate to the real-world events that inspired both films.

Box-office success and awards[edit]

When the movie was released the publisher Die Broschüre provided schools with material to help teachers "to prepare the visit to the movie theater“ as well as "reviewing it afterwards“. Furthermore, an official novel corresponding to the movie, written by Kerstin Winter, was published. The Wave was released with 279[29] copies in Germany on 13 March 2008. One day later it was first screened in Austrian movie theaters. Overall the movie attracted 2.5 million German viewers. [46]

The Wave received an award for the Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Frederick Lau) and the Bronze Lola in the category Best Feature Film at the German Film Awards in 2008 (Deutscher Filmpreis). Furthermore, Ueli Christen was nominated in the category Best Editing. In the same minute lead actor Jürgen Vogel was nominated in the category Best Actor at the European Film Awards 2008. Moreover, The Wave was screened at the Sundance Film Festival in the World Cinema - Dramatic section without receiving an award. The movie was also shortlisted for an Oscar nomination in the category Best Foreign Language Film, but lost out to The Baader Meinhof Complex.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jones, Ron (1972). "The Third Wave". Archived from the original on 24 February 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2016., and Jones, Ron (1976). "The Third Wave". The Wave Home. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Die Welle (The Wave) (2008)". boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ Jeff Dawson ...salutes a hit German film ... Sunday Times 31 Aug 2008

- ^ Note: This is actually the usual way for German students to address teachers. In itself, it is not specifically authoritarian; in this case, it means that Rainer Wenger had before been a highly unusually informal teacher who changes that policy now.

- ^ a b c Christa Hanetseder: Lehrer gegen Vorurteile. Zwei Experimente mit unerwarteter Dynamik In: ph akzente Nr. 4/2008, S. 16

- ^ a b c d Irene Jung: Keiner kann sagen, er hätte von nichts gewusst. In: Hamburger Abendblatt, 10. März 2008, S. 3

- ^ a b c d e f Ina Hochreuther: Die Schule und die Diktatur In: Stuttgarter Zeitung, 13. März 2008, S. 32

- ^ Ekkehard Knörrer: Der Mensch ist eben auch nur eine Ratte im Labor In: taz, 12. März 2008, S. 15

- ^ a b c d e f Dennis Gansel im Gespräch mit dem Hamburger Abendblatt, 10. März 2008, S. 3: „An den psychologischen Mechanismen hat sich nichts geändert“

- ^ a b c Daniel Kothenschulte: Der freie Wille In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 13. März 2008, S. 33

- ^ "Dennis Gansel riding on the crest of the wave". 4 February 2013.

- ^ Dennis Gansel im Gespräch mit Cinema, Nr. 4/2008, S. 36

- ^ Dennis Gansel im Gespräch mit Der Standard, 11. Februar 2008, S. 28: Faschismus ist für alle anziehend

- ^ a b c d Dennis Gansel im Gespräch mit den Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 10. März 2008, S. 12: „Widerstandsbiografien entstehen aus Zufällen“

- ^ a b c d e Ulrich Steller: Kapitel Filmische Mittel in: Die Welle. Materialien für den Unterricht. Hrsg. von Vera Conrad, München 2008. Abrufbar auf der offiziellen Seite des Filmverleihs Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Maximilian Probst: Macht durch Handeln! In: Die Zeit, 13. März 2008

- ^ a b Tobias Kniebe: Der Faschist in uns Archived 26 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 12. März 2008

- ^ a b Harald Pauli: Lass den Nazi raus! In: Focus, 10. März 2008, S. 68

- ^ a b c d e Christoph Cadenbach: Wie Schüler sich freudestrahlend in Faschisten verwandeln In: Spiegel Online, 10. März 2008

- ^ a b c d Ulrich Sonnenschein: Die Welle In: epd Film, März 2008, S. 46

- ^ a b Heiko Rosner: Das Ende der Unschuld In: Cinema, Nr. 4/2008, S. 34–36

- ^ Andreas Kilb: Auf Wiedersehen, Kinder In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 13. März 2008, S. 36

- ^ a b c d e Eva Maria Schlosser: Das Experiment entgleist In: Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 13. März 2008, S. 20

- ^ Julia Teichmann: Macht, Gemeinschaft, Disziplin In: Berliner Zeitung, 12. März 2008, S. 27

- ^ a b Sebastian Handke: Die Weißwäscher In: Der Tagesspiegel, 13. März 2008, S. 31

- ^ Gebhard Hölzl: Die Welle. In: Fränkische Nachrichten, 13. März 2008.

- ^ Mike Beilfuß: Die Welle In: film-dienst Nr. 6/2008, S. 53

- ^ "DIE WELLE - Interview: Ron Jones (Original Lehrer) eng / ger sub". YouTube. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Spiegel Online, 17. März 2008: Hu! Horton hört die Kassen klingeln

External links[edit]

- The Wave at IMDb

- The Wave at AllMovie

- The Wave Home Website with story history, FAQ, links, etc. by original Wave students

- guardian.co.uk Article