Ed Vaizey

The Lord Vaizey of Didcot | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2020 | |

| Minister of State for Culture and the Digital Economy[a] | |

| In office 14 May 2010 – 15 July 2016 | |

| Prime Minister | David Cameron |

| Preceded by | Siôn Simon |

| Succeeded by | Matt Hancock |

| Shadow Minister for Culture, Media and Sport | |

| In office 7 November 2006 – 6 May 2010 | |

| Leader | David Cameron |

| Preceded by | Malcolm Moss |

| Succeeded by | Gloria De Piero |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| Assumed office 10 September 2020 Life peerage | |

| Member of Parliament for Wantage | |

| In office 5 May 2005 – 6 November 2019 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Jackson |

| Succeeded by | David Johnston |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 June 1968 St Pancras, London, England |

| Political party | Conservative[b] |

| Spouse | Alex Holland |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Merton College, Oxford |

| Website | vaizey |

Edward Henry Butler Vaizey, Baron Vaizey of Didcot, PC (born 5 June 1968) is a British politician, media columnist, political commentator and barrister who was Minister for Culture, Communications and Creative Industries from 2010 to 2016. A member of the Conservative Party, he was Member of Parliament (MP) for Wantage from 2005 to 2019.

Early life[edit]

Vaizey was born in June 1968 in St Pancras, London.[1] He is the son of the late John Vaizey, a Labour (later Conservative) life peer, and the art historian Marina Vaizey (The Lady Vaizey CBE). His father's family is from South London. His mother's family, of Polish Jewish descent, is from New York City. He spent part of his childhood in Berkshire. He was educated at St Paul's School, London before reading history at Merton College, Oxford. Elected Librarian of the Oxford Union, he graduated with an upper second class degree. After leaving university, Vaizey worked for the Conservative MPs Kenneth Clarke and Michael Howard as an adviser on employment and education issues. He practised as a barrister for several years, in family law and child care.[2][3]

Personal life[edit]

Vaizey dated and proposed marriage to businesswoman and current UK MP Esther McVey.[4][5][6][7] He then dated and married Solicitor, Alexandra Mary-Jane Holland b.1970[8] on the 17 September 2005, in the chapel of the House of Commons.[9] Michael Gove was his Best Man and the wedding reception was held nearby at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in The Mall, London.[10][11][12][13] The couple share two children, Joseph and Martha.[14]

Political career[edit]

Vaizey first stood for Parliament at the 1997 general election, when he was the Conservative Party candidate for Bristol East. In the 2001 general election, he acted as an election aide to Iain Duncan Smith. He unsuccessfully stood at the 2002 local elections for the safe Labour ward of Harrow Road (based around the area of that name) in the City of Westminster.[15]

He is regarded as a moderniser within the Conservative Party, contributing in both policy and image terms. He was a speechwriter for Michael Howard, the then Leader of the Conservative Party, until December 2004, and editor of the Blue Books series which looked into new approaches to Conservative policy in areas such as health and transport.

Vaizey was one of Michael Howard's inner circle of advisers and a member of a group of Young Conservatives somewhat disparagingly referred to as the "Notting Hill Set" along with David Cameron—elected party leader in December 2005—George Osborne, Michael Gove, Nicholas Boles and Rachel Whetstone. Like Gove and Boles, he is a fellow of the Henry Jackson Society, and also a vice-chairman of Conservative Friends of Poland.[16]

Member of Parliament[edit]

In 2002, Vaizey was selected by Wantage Conservative Association to be its candidate for the 2005 general election to succeed the sitting MP, Robert Jackson, who subsequently crossed the floor to Labour. Vaizey won a two-thirds majority in the final ballot of members and was elected as MP in that election, receiving 22,394 votes. His majority was 8,017 over the Liberal Democrats; this represented 43% of the voters and a 1.9% swing from the Liberal Democrats to the Conservatives.

When first elected to the House of Commons, Vaizey became a member of the Standing Committee on the Consumer Credit Bill. Before being appointed to the Opposition frontbench he was a member of the Modernisation and Environmental Audit Select Committees and was Deputy Chairman of the Conservative's Globalisation and Global Poverty Policy Group.

In November 2006, Vaizey was appointed to the Conservative frontbench as a Shadow Minister for Culture, overseeing Arts and Broadcasting policy.

In the 2010 general election he received a vote of 29,284, which was 52% of the votes cast, winning an increased majority of 13,457. While the Conservative Party was in negotiations with the Lib Dems in the days after 6 May 2010, Vaizey was appearing regularly on television putting forward the Conservative viewpoint. In the 2015 general election Vaizey increased his majority to 21,749. In the 2017 general election Vaizey's majority was reduced but his share of the vote increased to 54.2%.

Vaizey was one of the group of 21 MPs who had the Conservative Whip removed in September 2019, sitting as an independent politician until having the whip restored on 29 October 2019. On 6 November 2019 Vaizey announced his decision not to stand for re-election in the 2019 general election.[17]

Ministerial career[edit]

In 2010, Vaizey was appointed as Minister for Culture, Communications and Creative Industries. with responsibilities in the Departments for Culture, Media and Sport and for Business, Innovation and Skills.[18] Vaizey was the longest serving Minister of Culture since the post was created in 1964, serving a total of 2,255 days, exceeding the total set by the first incumbent, Jennie Lee, by 186 days.[19][20]

Upon leaving office, over 150 senior figures from the arts and creative industries wrote to the Daily Telegraph to express their thanks for his service as Minister for Culture and the Digital Economy.[20] In 2011 he was mistakenly informed that he was to be Trade Minister, a post actually intended for Ed Davey.[21]

Vaizey supported continued membership of the European Union in the 2016 referendum and is supportive of the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom).[22]

As a minister, Vaizey upheld the policy of free entry to the UK's national museums.[23] Towards the end of his tenure, the Treasury introduced tax credits for theatre, orchestras and museums.[24] Vaizey also secured £150 million in capital funding from the Treasury to help reform museum storage.[25]

He oversaw the separation of English Heritage into two arms – a regulator, now known as Historic England, and a charity, English Heritage.[26] Vaizey also held responsibility for the creative industries and ensured the continuance of the film tax credits, as well as the introduction of tax credits for video games, television and visual effects.[27] As a result, the film industry became the second highest contributor to growth in the service sector in 2017, growing by 72.4% since 2014, compared to European growth of 8.5%. During his tenure, the creative industries grew at three times the rate of the UK economy as a whole.[28] He was dismissed as a minister by Theresa May on 14 July 2016, and returned to the backbenches.[29] He was appointed a member of the Privy Council in July 2016.

Expenses claims[edit]

On 18 May 2009, The Daily Telegraph reported that receipts submitted by Vaizey show that he ordered a £467 sofa, a £544 chair, a £280.50 low table and a £671 table in February 2007 from Oka, a furniture shop run by Annabel Astor. The Commons Fees Office initially rejected the claim as the receipt said that the furniture was due to be delivered to Vaizey's home address in West London, but was later paid when Vaizey advised the Fees Office that the furniture was intended for his second home at his Wantage constituency. Vaizey told The Daily Telegraph that he and his wife "had it delivered to London because we would be in to collect it and we were driving down with it".[30]

When these claims became public, Vaizey said that he had repaid the cost of the Oka furniture and the antique chair which he had bought with taxpayers' money: "I accept that the £300 armchair was an antique item and therefore that claim should not have been made. I also accept that the Oka items could be deemed as being of higher quality than necessary. I have paid back both these claims. I have not claimed for any other furniture bought for my constituency home at any time before or since."[30] Vaizey has described himself as "relatively affluent".[31]

In November 2011, it was further reported that Vaizey had submitted expenses claims of 8p for a 350-yard car journey and 16p for a 700-yard journey.[32]

Peerage[edit]

It was announced on 31 July 2020 that Vaizey was to be raised to the peerage in the 2019 Dissolution Honours.[33] He was created Baron Vaizey of Didcot, of Wantage in the County of Oxfordshire in the afternoon of 1 September.[34][35]

He made his maiden speech in the House of Lords on 21 September 2020.

Media career[edit]

Vaizey has been a regular commentator for the Conservative Party in the broadcast and news media. He wrote regular comment pieces for The Guardian between 1998 and 2005 and has contributed articles to The Sunday Times, The Times and The Daily Telegraph. He briefly wrote editorials for the Evening Standard. Vaizey is also a regular broadcaster, having appeared on Fi Glover's and Edwina Currie's shows on BBC Radio 5 Live, as a regular panelist on Channel 5's The Wright Stuff, BBC Radio 4's Despatch Box and Westminster Hour, and occasionally presented People and Politics on the BBC World Service. Vaizey is a regular contributor on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, and since December 2022, Vaizey has been a regular presenter on Times Radio.

On 24 September 2010, Vaizey was named tenth in the 2010 Guardian Film Power 100 list.[36] He played a cameo role as an Oxfordshire MP in the 2012 film Tortoise in Love.[37]

Other work[edit]

Subsequent to leaving office as Minister for Culture, Communications and Creative Industries, Vaizey became a trustee of the National Youth Theatre and the international charity BritDoc, which supports long-form documentary making, both of which roles are unpaid.[38] Vaizey is also a trustee of London Music Masters, a charity which provides children from disadvantaged backgrounds access to a high quality music education.[39]

He was appointed the unpaid chairman of Creative Fuse NE, a programme overseen by five universities in North East England to look at the importance of fusing creativity and technology.[38]

Vaizey took a role with LionTree Advisors who paid a salary of £50,000 for one day's work per week. The Advisory Committee on Business Appointments approved his application to work for the investment bank, which specialises in media and technology mergers and acquisitions, despite Vaizey's having met the firm on "official business" three times in his final months as minister.[40]

He is a past president of the Old Pauline Club, the alumni association of St Paul's School which he attended as a pupil.[41][42]

Bibliography[edit]

- A Blue Tomorrow – New Visions for Modern Conservatives (2001) (ed. with Michael Gove and Nicholas Boles). ISBN 1-84275-027-5

- Blue Book on Health: Conservative Visions for Health Policy (2002) ISBN 1-84275-043-7

- Blue Book on Transport: Conservative Visions for Transport Policy (ed with Michael McManus) (2002) ISBN 1-84275-044-5

- Blue Book on Education (ed with Michael McManus) (2003)

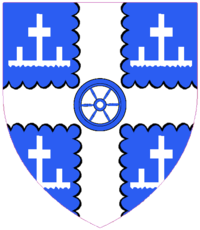

Arms[edit]

|

|

Notes[edit]

- ^ Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Culture, Communications and Creative Industries (2010–2014).

- ^ Whip suspended from 3 September to 29 October 2019.

References[edit]

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Londoner's Diary: Will Fifa farce put a strain on royal relations?". Evening Standard. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Debrett's People of Today

- ^ "You probably won't have heard of them ... but they're the Tory future". The Independent. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ https://www.pressreader.com/. Retrieved 20 December 2023 – via PressReader.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Esther McVey: I want children but no one has wound up my biological clock". The Telegraph. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Midgley, Dominic (17 July 2014). "Esther McVey's ambition: The ex-TV presenter is now striding into Davi". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Alexandra Mary Jane VAIZEY personal appointments - Find and update company information - GOV.UK". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "MP fixes date to tie the knot". Oxford Mail. 19 July 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "The two Davids unite. Now the third must decide". The Telegraph. 18 September 2005. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Solicitors Law Society".

- ^ "ICA | ICA – Institute of Contemporary Arts". www.ica.art. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "ICA | Venue Hire". www.ica.art. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "MP celebrates second child". Oxford Mail. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Local Elections Archive Project — Harrow Road Ward". www.andrewteale.me.uk. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Conservative Friends of Poland website Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vaizey, Ed [@edvaizey] (6 November 2019). "After much reflection I have decided not to stand at the next election" (Tweet). Retrieved 6 November 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Ed Vaizey". GOV.UK.

- ^ Snow, Georgia (12 January 2016). "Ed Vaizey becomes UK's longest serving arts minister". thestage.co.uk. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Letters: Saluting Ed Vaizey, a true friend to the creative industries". The Telegraph. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Burrell, Ian (27 September 2012). "Ed Vaizey: 'I was once made Minister for Trade – for about half an hour'". The Independent. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Dixon, Anabelle (9 November 2017). "40 Brexit troublemakers to watch: Ed Vaizey". POLITICO. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (4 January 2014). "Conservatives rule out museum entry charges after 2015 election". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Voting record - Ed Vaizey MP, Wantage". TheyWorkForYou. mySociety. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "UK government's first white paper in over half a century". artmediaagency.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "All change at English heritage". cgms.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Stuart, Keith (15 July 2015). "Ed Vaizey – video games are as important to British culture as cinema". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (26 July 2017). "UK film industry on a roll as it helps keep economy growing". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Asthana, Anushka (5 October 2017). "MPs will want Theresa May to quit, says former minister Ed Vaizey". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ a b Hope, Christopher (18 May 2009). "Ed Vaizey had £2,000 furniture delivered to 'wrong address'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ "www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk". Archived from the original on 9 April 2011.

- ^ "MP claimed 8p for car journey". The Oxford Times. 5 November 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Dissolution Peerages 2019" (PDF). GOV.UK. 31 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Lord Vaizey of Didcot". UK Parliament. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Crown Office". The London Gazette. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter; Kermode, Mark (24 September 2010). "Film Power 100: the full list". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Village film Tortoise In Love gets London premiere". BBC News. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Ed Vaizey: Profile". TheyWorkForYou. mySociety. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Ed Vaizey MP – London Music Masters – Learning".

- ^ "Digital dividend". Private Eye. London: Pressdram Ltd. 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Committees". Old Pauline Club. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Welcome from the President". Old Pauline Club. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage. 1985.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Profile Archived 3 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine at the Conservative Party

- Wantage and Didcot Conservatives

- Profile at Parliament of the United Kingdom

- Contributions in Parliament at Hansard

- Voting record at Public Whip

- Record in Parliament at TheyWorkForYou

- Video game industry interview with Ed Vaizey, Bruceongames, 27 July 2009

- Art interview with Ed Vaizey, Artforums.co.uk, 15 December 2009

- 1968 births

- Alumni of Merton College, Oxford

- British male journalists

- British special advisers

- Conservative Party (UK) life peers

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- Independent members of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

- English barristers

- English people of American descent

- English people of Jewish descent

- Government ministers of the United Kingdom

- Living people

- Members of the Middle Temple

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People from Berkshire

- People from Wantage

- Politicians from Essex

- People educated at Colet Court

- People educated at St Paul's School, London

- The Guardian journalists

- The Sunday Times people

- The Times people

- UK MPs 2005–2010

- UK MPs 2010–2015

- UK MPs 2015–2017

- UK MPs 2017–2019

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- Sons of life peers

- Children of peers and peeresses created life peers