Groupthink

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Cohesiveness, or the desire for cohesiveness, in a group may produce a tendency among its members to agree at all costs.[1] This causes the group to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation.[2][3]

Groupthink is a construct of social psychology but has an extensive reach and influences literature in the fields of communication studies, political science, management, and organizational theory,[4] as well as important aspects of deviant religious cult behaviour.[5][6]

Overview[edit]

Groupthink is sometimes stated to occur (more broadly) within natural groups within the community, for example to explain the lifelong different mindsets of those with differing political views (such as "conservatism" and "liberalism" in the U.S. political context[7] or the purported benefits of team work vs. work conducted in solitude).[8] However, this conformity of viewpoints within a group does not mainly involve deliberate group decision-making, and might be better explained by the collective confirmation bias of the individual members of the group. [citation needed]

The term was coined in 1952 by William H. Whyte Jr.[9] Most of the initial research on groupthink was conducted by Irving Janis, a research psychologist from Yale University.[10] Janis published an influential book in 1972, which was revised in 1982.[11][12] Janis used the Bay of Pigs disaster (the failed invasion of Castro's Cuba in 1961) and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 as his two prime case studies. Later studies have evaluated and reformulated his groupthink model.[13][14]

Groupthink requires individuals to avoid raising controversial issues or alternative solutions, and there is loss of individual creativity, uniqueness and independent thinking. The dysfunctional group dynamics of the "ingroup" produces an "illusion of invulnerability" (an inflated certainty that the right decision has been made). Thus the "ingroup" significantly overrates its own abilities in decision-making and significantly underrates the abilities of its opponents (the "outgroup"). Furthermore, groupthink can produce dehumanizing actions against the "outgroup". Members of a group can often feel under peer pressure to "go along with the crowd" for fear of "rocking the boat" or of how their speaking out will be perceived by the rest of the group. Group interactions tend to favor clear and harmonious agreements and it can be a cause for concern when little to no new innovations or arguments for better policies, outcomes and structures are called to question. (McLeod). Groupthink can often be referred to as a group of “yes men”[citation needed] because group activities and group projects in general make it extremely easy to pass on not offering constructive opinions.

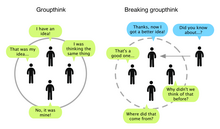

Some methods that have been used to counteract group think in the past is selecting teams from more diverse backgrounds, and even mixing men and women for groups (Kamalnath). Groupthink can be considered by many to be a detriment to companies, organizations and in any work situations. Most positions that are senior level need individuals to be independent in their thinking. There is a positive correlation found between outstanding executives and decisiveness (Kelman). Groupthink also prohibits an organization from moving forward and innovating if no one ever speaks up and says something could be done differently.

Antecedent factors such as group cohesiveness, faulty group structure, and situational context (e.g., community panic) play into the likelihood of whether or not groupthink will impact the decision-making process.

History[edit]

William H. Whyte Jr. derived the term from George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, and popularized it in 1952 in Fortune magazine:

Groupthink being a coinage – and, admittedly, a loaded one – a working definition is in order. We are not talking about mere instinctive conformity – it is, after all, a perennial failing of mankind. What we are talking about is a rationalized conformity – an open, articulate philosophy which holds that group values are not only expedient but right and good as well.[9][15]

Groupthink was Whyte's diagnosis of the malaise affecting both the study and practice of management (and, by association, America) in the 1950s. Whyte was dismayed that employees had subjugated themselves to the tyranny of groups, which crushed individuality and were instinctively hostile to anything or anyone that challenged the collective view.[16]

American psychologist Irving Janis (Yale University) pioneered the initial research on the groupthink theory. He does not cite Whyte, but coined the term again by analogy with "doublethink" and similar terms that were part of the newspeak vocabulary in the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. He initially defined groupthink as follows:

I use the term groupthink as a quick and easy way to refer to the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action. Groupthink is a term of the same order as the words in the newspeak vocabulary George Orwell used in his dismaying world of 1984. In that context, groupthink takes on an invidious connotation. Exactly such a connotation is intended, since the term refers to a deterioration in mental efficiency, reality testing and moral judgments as a result of group pressures.[10]: 43

He went on to write:

The main principle of groupthink, which I offer in the spirit of Parkinson's Law, is this: "The more amiability and esprit de corps there is among the members of a policy-making ingroup, the greater the danger that independent critical thinking will be replaced by groupthink, which is likely to result in irrational and dehumanizing actions directed against outgroups".[10]: 44

Janis set the foundation for the study of groupthink starting with his research in the American Soldier Project where he studied the effect of extreme stress on group cohesiveness. After this study he remained interested in the ways in which people make decisions under external threats. This interest led Janis to study a number of "disasters" in American foreign policy, such as failure to anticipate the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (1941); the Bay of Pigs Invasion fiasco (1961); and the prosecution of the Vietnam War (1964–67) by President Lyndon Johnson. He concluded that in each of these cases, the decisions occurred largely because of groupthink, which prevented contradictory views from being expressed and subsequently evaluated.

After the publication of Janis' book Victims of Groupthink in 1972,[11] and a revised edition with the title Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes in 1982,[12] the concept of groupthink was used[by whom?] to explain many other faulty decisions in history. These events included Nazi Germany's decision to invade the Soviet Union in 1941, the Watergate scandal and others. Despite the popularity of the concept of groupthink, fewer than two dozen studies addressed the phenomenon itself following the publication of Victims of Groupthink, between the years 1972 and 1998.[4]: 107 This was surprising considering how many fields of interests it spans, which include political science, communications, organizational studies, social psychology, management, strategy, counseling, and marketing. One can most likely explain this lack of follow-up in that group research is difficult to conduct, groupthink has many independent and dependent variables, and it is unclear "how to translate [groupthink's] theoretical concepts into observable and quantitative constructs".[4]: 107–108

Nevertheless, outside research psychology and sociology, wider culture has come to detect groupthink in observable situations, for example:

- " [...] critics of Twitter point to the predominance of the hive mind in such social media, the kind of groupthink that submerges independent thinking in favor of conformity to the group, the collective"[17]

- "[...] leaders often have beliefs which are very far from matching reality and which can become more extreme as they are encouraged by their followers. The predilection of many cult leaders for abstract, ambiguous, and therefore unchallengeable ideas can further reduce the likelihood of reality testing, while the intense milieu control exerted by cults over their members means that most of the reality available for testing is supplied by the group environment. This is seen in the phenomenon of 'groupthink', alleged to have occurred, notoriously, during the Bay of Pigs fiasco."[18]

- "Groupthink by Compulsion [...] [G]roupthink at least implies voluntarism. When this fails, the organization is not above outright intimidation. [...] In [a nationwide telecommunications company], refusal by the new hires to cheer on command incurred consequences not unlike the indoctrination and brainwashing techniques associated with a Soviet-era gulag."[19]

Symptoms[edit]

To make groupthink testable, Irving Janis devised eight symptoms indicative of groupthink:[20]

Type I: Overestimations of the group — its power and morality

- Illusions of invulnerability creating excessive optimism and encouraging risk taking.

- Unquestioned belief in the morality of the group, causing members to ignore the consequences of their actions.

Type II: Closed-mindedness

- Rationalizing warnings that might challenge the group's assumptions.

- Stereotyping those who are opposed to the group as weak, evil, biased, spiteful, impotent, or stupid.

Type III: Pressures toward uniformity

- Self-censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus.

- Illusions of unanimity among group members, silence is viewed as agreement.

- Direct pressure to conform placed on any member who questions the group, couched in terms of "disloyalty".

- Mindguards— self-appointed members who shield the group from dissenting information.

When a group exhibits most of the symptoms of groupthink, the consequences of a failing decision process can be expected: incomplete analysis of the other options, incomplete analysis of the objectives, failure to examine the risks associated with the favored choice, failure to reevaluate the options initially rejected, poor information research, selection bias in available information processing, failure to prepare for a back-up plan.[11]

Causes[edit]

Irving Janis identified three antecedent conditions to groupthink:[11]: 9

- High group cohesiveness: Cohesiveness is the main factor that leads to groupthink. Groups that lack cohesiveness can of course make bad decisions, but they do not experience groupthink. In a cohesive group, members avoid speaking out against decisions, avoid arguing with others, and work towards maintaining friendly relationships in the group. If cohesiveness gets to such a level that there are no longer disagreements between members, then the group is ripe for groupthink.

- Deindividuation: Group cohesiveness becomes more important than individual freedom of expression.

- Illusions of unanimity: Members perceive falsely that everyone agrees with the group's decision; silence is seen as consent. Janis noted that the unity of group members was mere illusion. Members may disagree with the organizations' decision, but go along with the group for many reasons, such as maintaining their group status and avoiding conflict with managers or workmates. Such members think that suggesting opinions contrary to others may lead to isolation from the group.

- Structural faults: The group is organized in ways that disrupt the communication of information, or the group carelessly makes decisions.

- Insulation of the group: This can promote the development of unique, inaccurate perspectives on issues the group is dealing with, which can then lead to faulty solutions to the problem.

- Lack of impartial leadership: Leaders control the group discussion, by planning what will be discussed, allowing only certain questions to be asked, and asking for opinions of only certain people in the group. Closed-style leadership is when leaders announce their opinions on the issue before the group discusses the issue together. Open-style leadership is when leaders withhold their opinion until a later time in the discussion. Groups with a closed-style leader are more biased in their judgments, especially when members had a high degree of certainty.

- Lack of norms requiring methodological procedures.

- Homogeneity of members' social backgrounds and ideology.

- Situational context:

- Highly stressful external threats: High-stake decisions can create tension and anxiety; group members may cope with this stress in irrational ways. Group members may rationalize their decision by exaggerating the positive consequences and minimizing the possible negative consequences. In attempt to minimize the stressful situation, the group decides quickly and allows little to no discussion or disagreement. Groups under high stress are more likely to make errors, lose focus of the ultimate goal, and use procedures that members know have not been effective in the past.

- Recent failures: These can lead to low self-esteem, resulting in agreement with the group for fear of being seen as wrong.

- Excessive difficulties in decision-making tasks.

- Time pressures: Group members are more concerned with efficiency and quick results than with quality and accuracy. Time pressures can also lead group members to overlook important information.

- Moral dilemmas.[clarification needed]

Although it is possible for a situation to contain all three of these factors, all three are not always present even when groupthink is occurring. Janis considered a high degree of cohesiveness to be the most important antecedent to producing groupthink, and always present when groupthink was occurring; however, he believed high cohesiveness would not always produce groupthink. A very cohesive group abides with all group norms; but whether or not groupthink arises is dependent on what the group norms are. If the group encourages individual dissent and alternative strategies to problem solving, it is likely that groupthink will be avoided even in a highly cohesive group. This means that high cohesion will lead to groupthink only if one or both of the other antecedents is present, situational context being slightly more likely than structural faults to produce groupthink.[21]

A 2018 study found that absence of a tenured Project leader can also create conditions for groupthink to prevail. Presence of an ‘experienced’ project manager can reduce the likelihood of groupthink by taking steps like critically analysing ideas, promoting open communication, encouraging diverse perspectives, and raising team awareness of groupthink symptoms. [22]

It was found that among people who have Bicultural identity, those with highly integrated Bicultural identity as opposed to less integrated were more prone to groupthink.[23] In another 2022 study in Tanzania, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions come into play. It was observed that in high power distance societies, individuals are hesitant to voice dissent, deferring to leaders' preferences in making decisions. Furthermore, as Tanzania is a collectivist society, community interests supersede those of individuals. The combination of high power distance & collectivism creates optimal conditions for groupthink to occur.[24]

Prevention[edit]

As observed by Aldag and Fuller (1993), the groupthink phenomenon seems to rest on a set of unstated and generally restrictive assumptions:[25]

- The purpose of group problem solving is mainly to improve decision quality

- Group problem solving is considered a rational process.

- Benefits of group problem solving:

- variety of perspectives

- more information about possible alternatives

- better decision reliability

- dampening of biases

- social presence effects

- Groupthink prevents these benefits due to structural faults and provocative situational context

- Groupthink prevention methods will produce better decisions

- An illusion of well-being is presumed to be inherently dysfunctional.

- Group pressures towards consensus lead to concurrence-seeking tendencies.

It has been thought that groups with the strong ability to work together will be able to solve dilemmas in a quicker and more efficient fashion than an individual. Groups have a greater amount of resources which lead them to be able to store and retrieve information more readily and come up with more alternative solutions to a problem. There was a recognized downside to group problem solving in that it takes groups more time to come to a decision and requires that people make compromises with each other. However, it was not until the research of Janis appeared that anyone really considered that a highly cohesive group could impair the group's ability to generate quality decisions. Tight-knit groups may appear to make decisions better because they can come to a consensus quickly and at a low energy cost; however, over time this process of decision-making may decrease the members' ability to think critically. It is, therefore, considered by many to be important to combat the effects of groupthink.[21]

According to Janis, decision-making groups are not necessarily destined to groupthink. He devised ways of preventing groupthink:[11]: 209–215

- Leaders should assign each member the role of "critical evaluator". This allows each member to freely air objections and doubts.

- Leaders should not express an opinion when assigning a task to a group.

- Leaders should absent themselves from many of the group meetings to avoid excessively influencing the outcome.

- The organization should set up several independent groups, working on the same problem.

- All effective alternatives should be examined.

- Each member should discuss the group's ideas with trusted people outside of the group.

- The group should invite outside experts into meetings. Group members should be allowed to discuss with and question the outside experts.

- At least one group member should be assigned the role of devil's advocate. This should be a different person for each meeting.

The devil's advocate in a group may provide questions and insight which contradict the majority group in order to avoid groupthink decisions.[26] A study by Ryan Hartwig confirms that the devil's advocacy technique is very useful for group problem-solving.[27] It allows for conflict to be used in a way that is most-effective for finding the best solution so that members will not have to go back and find a different solution if the first one fails. Hartwig also suggests that the devil's advocacy technique be incorporated with other group decision-making models such as the functional theory to find and evaluate alternative solutions. The main idea of the devil's advocacy technique is that somewhat structured conflict can be facilitated to not only reduce groupthink, but to also solve problems.

Diversity of all kinds is also instrumental in preventing groupthink. Individuals with varying backgrounds, thought, professional & life experiences etc. can offer unique perspectives & challenge assumptions.[28][29] In a 2004 study, a diverse team of problem-solver outperformed a team consisting of best problem solvers as they start to think alike.[30]

Psychological safety, emphasized by Edmondson & Lei[31] and Hirak et al.[32], is crucial for effective group performance. It involves creating an environment that encourages learning and removes barriers perceived as threats by team members. Edmondson et al.[33] demonstrated variations in psychological safety based on work type, hierarchy, and leadership effectiveness, highlighting its importance in employee development and fostering a culture of learning within organizations.[34]

A similar term to groupthink is the Abilene paradox, another phenomenon that is detrimental when working in groups. When organizations fall into the Abilene paradox, they take actions in contradiction to what their perceived goals may be and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve.[35] Failure to communicate desires or beliefs can cause the Abilene paradox.

Examples[edit]

The Watergate scandal is an example of this.[citation needed] Before the scandal had occurred, a meeting took place where they discussed the issue. One of Nixon's campaign aides was unsure if he should speak up and give his input. If he had voiced his disagreement with the group's decision, it is possible that the scandal could have been avoided.[citation needed]

After the Bay of Pigs invasion fiasco, President John F. Kennedy sought to avoid groupthink during the Cuban Missile Crisis using "vigilant appraisal".[12]: 148–153 During meetings, he invited outside experts to share their viewpoints, and allowed group members to question them carefully. He also encouraged group members to discuss possible solutions with trusted members within their separate departments, and he even divided the group up into various sub-groups, to partially break the group cohesion. Kennedy was deliberately absent from the meetings, so as to avoid pressing his own opinion.

Cass Sunstein reports that introverts can sometimes be silent in meetings with extroverts; he recommends explicitly asking for each person's opinion, either during the meeting or afterwards in one-on-one sessions. Sunstein points to studies showing groups with a high level of internal socialization and happy talk are more prone to bad investment decisions due to groupthink, compared with groups of investors who are relative strangers and more willing to be argumentative. To avoid group polarization, where discussion with like-minded people drives an outcome further to an extreme than any of the individuals favored before the discussion, he recommends creating heterogeneous groups which contain people with different points of view. Sunstein also points out that people arguing a side they do not sincerely believe (in the role of devil's advocate) tend to be much less effective than a sincere argument. This can be accomplished by dissenting individuals, or a group like a Red Team that is expected to pursue an alternative strategy or goal "for real".[36]

Empirical findings and meta-analysis[edit]

Testing groupthink in a laboratory is difficult because synthetic settings remove groups from real social situations, which ultimately changes the variables conducive or inhibitive to groupthink.[37] Because of its subjective nature, researchers have struggled to measure groupthink as a complete phenomenon, instead frequently opting to measure its particular factors. These factors range from causal to effectual[clarification needed] and focus on group and situational aspects.[38][39]

Park (1990) found that "only 16 empirical studies have been published on groupthink", and concluded that they "resulted in only partial support of his [Janis's] hypotheses".[40]: 230 Park concludes, "despite Janis' claim that group cohesiveness is the major necessary antecedent factor, no research has shown a significant main effect of cohesiveness on groupthink."[40]: 230 Park also concludes that research does not support Janis' claim that cohesion and leadership style interact to produce groupthink symptoms.[40] Park presents a summary of the results of the studies analyzed. According to Park, a study by Huseman and Drive (1979) indicates groupthink occurs in both small and large decision-making groups within businesses.[40] This results partly from group isolation within the business. Manz and Sims (1982) conducted a study showing that autonomous work groups are susceptible to groupthink symptoms in the same manner as decisions making groups within businesses.[40][41] Fodor and Smith (1982) produced a study revealing that group leaders with high power motivation create atmospheres more susceptible to groupthink.[40][42] Leaders with high power motivation possess characteristics similar to leaders with a "closed" leadership style—an unwillingness to respect dissenting opinion. The same study indicates that level of group cohesiveness is insignificant in predicting groupthink occurrence. Park summarizes a study performed by Callaway, Marriott, and Esser (1985) in which groups with highly dominant members "made higher quality decisions, exhibited lowered state of anxiety, took more time to reach a decision, and made more statements of disagreement/agreement".[40]: 232 [43] Overall, groups with highly dominant members expressed characteristics inhibitory to groupthink. If highly dominant members are considered equivalent to leaders with high power motivation, the results of Callaway, Marriott, and Esser contradict the results of Fodor and Smith. A study by Leana (1985) indicates the interaction between level of group cohesion and leadership style is completely insignificant in predicting groupthink.[40][44] This finding refutes Janis' claim that the factors of cohesion and leadership style interact to produce groupthink. Park summarizes a study by McCauley (1989) in which structural conditions of the group were found to predict groupthink while situational conditions did not.[14][40] The structural conditions included group insulation, group homogeneity, and promotional leadership. The situational conditions included group cohesion. These findings refute Janis' claim about group cohesiveness predicting groupthink.

Overall, studies on groupthink have largely focused on the factors (antecedents) that predict groupthink. Groupthink occurrence is often measured by number of ideas/solutions generated within a group, but there is no uniform, concrete standard by which researchers can objectively conclude groupthink occurs.[37] The studies of groupthink and groupthink antecedents reveal a mixed body of results. Some studies indicate group cohesion and leadership style to be powerfully predictive of groupthink, while other studies indicate the insignificance of these factors. Group homogeneity and group insulation are generally supported as factors predictive of groupthink.

Case studies[edit]

Politics and military[edit]

Groupthink can have a strong hold on political decisions and military operations, which may result in enormous wastage of human and material resources. Highly qualified and experienced politicians and military commanders sometimes make very poor decisions when in a suboptimal group setting. Scholars such as Janis and Raven attribute political and military fiascoes, such as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the Vietnam War, and the Watergate scandal, to the effect of groupthink.[12][45] More recently, Dina Badie argued that groupthink was largely responsible for the shift in the U.S. administration's view on Saddam Hussein that eventually led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States.[46] After the September 11 attacks, "stress, promotional leadership, and intergroup conflict" were all factors that gave rise to the occurrence of groupthink.[46]: 283 Political case studies of groupthink serve to illustrate the impact that the occurrence of groupthink can have in today's political scene.

Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis[edit]

The United States Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961 was the primary case study that Janis used to formulate his theory of groupthink.[10] The invasion plan was initiated by the Eisenhower administration, but when the Kennedy administration took over, it "uncritically accepted" the plan of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).[10]: 44 When some people, such as Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Senator J. William Fulbright, attempted to present their objections to the plan, the Kennedy team as a whole ignored these objections and kept believing in the morality of their plan.[10]: 46 Eventually Schlesinger minimized his own doubts, performing self-censorship.[10]: 74 The Kennedy team stereotyped Fidel Castro and the Cubans by failing to question the CIA about its many false assumptions, including the ineffectiveness of Castro's air force, the weakness of Castro's army, and the inability of Castro to quell internal uprisings.[10]: 46

Janis argued the fiasco that ensued could have been prevented if the Kennedy administration had followed the methods to preventing groupthink adopted during the Cuban Missile Crisis, which took place just one year later in October 1962. In the latter crisis, essentially the same political leaders were involved in decision-making, but this time they learned from their previous mistake of seriously under-rating their opponents.[10]: 76

Pearl Harbor[edit]

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, is a prime example of groupthink. A number of factors such as shared illusions and rationalizations contributed to the lack of precaution taken by U.S. Navy officers based in Hawaii. The United States had intercepted Japanese messages and they discovered that Japan was arming itself for an offensive attack somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. Washington took action by warning officers stationed at Pearl Harbor, but their warning was not taken seriously. They assumed that the Empire of Japan was taking measures in the event that their embassies and consulates in enemy territories were usurped.

The U.S. Navy and Army in Pearl Harbor also shared rationalizations about why an attack was unlikely. Some of them included:[12]: 83, 85

- "The Japanese would never dare attempt a full-scale surprise assault against Hawaii because they would realize that it would precipitate an all-out war, which the United States would surely win."

- "The Pacific Fleet concentrated at Pearl Harbor was a major deterrent against air or naval attack."

- "Even if the Japanese were foolhardy to send their carriers to attack us [the United States], we could certainly detect and destroy them in plenty of time."

- "No warships anchored in the shallow water of Pearl Harbor could ever be sunk by torpedo bombs launched from enemy aircraft."

Space Shuttle Challenger disaster[edit]

On January 28, 1986, the US launched the space shuttle Challenger. This was to be monumental for NASA, as a high school teacher was among the crew and was to be the first American civilian in space. NASA's engineering and launch teams rely on group work, and in order to launch the shuttle the team members must affirm each system is functioning nominally. The Thiokol engineers who designed and built the Challenger's rocket boosters warned that the temperature for the day of the launch could result in total failure of the vehicles and deaths of the crew.[47] The launch resulted in disaster and grounded space shuttle flights for nearly three years.

The Challenger case was subject to a more quantitatively oriented test of Janis's groupthink model performed by Esser and Lindoerfer, who found clear signs of positive antecedents to groupthink in the critical decisions concerning the launch of the shuttle.[48] The day of the launch was rushed for publicity reasons. NASA wanted to captivate and hold the attention of America. Having civilian teacher Christa McAuliffe on board to broadcast a live lesson, and the possible mention by president Ronald Reagan in the State of the Union address, were opportunities NASA deemed critical to increasing interest in its potential civilian space flight program. The schedule NASA set out to meet was, however, self-imposed. It seemed incredible to many that an organization with a perceived history of successful management would have locked itself into a schedule it had no chance of meeting.[49]

Corporate world[edit]

In the corporate world, ineffective and suboptimal group decision-making can negatively affect the health of a company and cause a considerable amount of monetary loss.

Swissair[edit]

Aaron Hermann and Hussain Rammal illustrate the detrimental role of groupthink in the collapse of Swissair, a Swiss airline company that was thought to be so financially stable that it earned the title the "Flying Bank".[50] The authors argue that, among other factors, Swissair carried two symptoms of groupthink: the belief that the group is invulnerable and the belief in the morality of the group.[50]: 1056 In addition, before the fiasco, the size of the company board was reduced, subsequently eliminating industrial expertise. This may have further increased the likelihood of groupthink.[50]: 1055 With the board members lacking expertise in the field and having somewhat similar background, norms, and values, the pressure to conform may have become more prominent.[50]: 1057 This phenomenon is called group homogeneity, which is an antecedent to groupthink. Together, these conditions may have contributed to the poor decision-making process that eventually led to Swissair's collapse.

Marks & Spencer and British Airways[edit]

Another example of groupthink from the corporate world is illustrated in the United Kingdom-based companies Marks & Spencer and British Airways. The negative impact of groupthink took place during the 1990s as both companies released globalization expansion strategies. Researcher Jack Eaton's content analysis of media press releases revealed that all eight symptoms of groupthink were present during this period. The most predominant symptom of groupthink was the illusion of invulnerability as both companies underestimated potential failure due to years of profitability and success during challenging markets. Up until the consequence of groupthink erupted they were considered blue chips and darlings of the London Stock Exchange. During 1998–1999 the price of Marks & Spencer shares fell from 590 to less than 300 and that of British Airways from 740 to 300. Both companies had previously been prominently featured in the UK press and media for more positive reasons, reflecting national pride in their undeniable sector-wide performance.[51]

Sports[edit]

Recent literature of groupthink attempts to study the application of this concept beyond the framework of business and politics. One particularly relevant and popular arena in which groupthink is rarely studied is sports. The lack of literature in this area prompted Charles Koerber and Christopher Neck to begin a case-study investigation that examined the effect of groupthink on the decision of the Major League Umpires Association (MLUA) to stage a mass resignation in 1999. The decision was a failed attempt to gain a stronger negotiating stance against Major League Baseball.[52]: 21 Koerber and Neck suggest that three groupthink symptoms can be found in the decision-making process of the MLUA. First, the umpires overestimated the power that they had over the baseball league and the strength of their group's resolve. The union also exhibited some degree of closed-mindedness with the notion that MLB is the enemy. Lastly, there was the presence of self-censorship; some umpires who disagreed with the decision to resign failed to voice their dissent.[52]: 25 These factors, along with other decision-making defects, led to a decision that was suboptimal and ineffective.

Recent developments[edit]

Ubiquity model[edit]

Researcher Robert Baron (2005) contends that the connection between certain antecedents which Janis believed necessary has not been demonstrated by the current collective body of research on groupthink. He believes that Janis' antecedents for groupthink are incorrect, and argues that not only are they "not necessary to provoke the symptoms of groupthink, but that they often will not even amplify such symptoms".[53] As an alternative to Janis' model, Baron proposed a ubiquity model of groupthink. This model provides a revised set of antecedents for groupthink, including social identification, salient norms, and low self-efficacy.

General group problem-solving (GGPS) model[edit]

Aldag and Fuller (1993) argue that the groupthink concept was based on a "small and relatively restricted sample" that became too broadly generalized.[25] Furthermore, the concept is too rigidly staged and deterministic. Empirical support for it has also not been consistent. The authors compare groupthink model to findings presented by Maslow and Piaget; they argue that, in each case, the model incites great interest and further research that, subsequently, invalidate the original concept. Aldag and Fuller thus suggest a new model called the general group problem-solving (GGPS) model, which integrates new findings from groupthink literature and alters aspects of groupthink itself.[25]: 534 The primary difference between the GGPS model and groupthink is that the former is more value neutral and more political.[25]: 544

Reexamination[edit]

Later scholars have re-assessed the merit of groupthink by reexamining case studies that Janis originally used to buttress his model. Roderick Kramer (1998) believed that, because scholars today have a more sophisticated set of ideas about the general decision-making process and because new and relevant information about the fiascos have surfaced over the years, a reexamination of the case studies is appropriate and necessary.[54] He argues that new evidence does not support Janis' view that groupthink was largely responsible for President Kennedy's and President Johnson's decisions in the Bay of Pigs Invasion and U.S. escalated military involvement in the Vietnam War, respectively. Both presidents sought the advice of experts outside of their political groups more than Janis suggested.[54]: 241 Kramer also argues that the presidents were the final decision-makers of the fiascos; while determining which course of action to take, they relied more heavily on their own construals of the situations than on any group-consenting decision presented to them.[54]: 241 Kramer concludes that Janis' explanation of the two military issues is flawed and that groupthink has much less influence on group decision-making than is popularly believed.

Groupthink, while it is thought to be avoided, does have some positive effects. Choi and Kim[55] found that group identity traits such as believing in the group's moral superiority, were linked to less concurrence seeking, better decision-making, better team activities, and better team performance. This study also showed that the relationship between groupthink and defective decision making was insignificant. These findings mean that in the right circumstances, groupthink does not always have negative outcomes. It also questions the original theory of groupthink.

Reformulation[edit]

Scholars are challenging the original view of groupthink proposed by Janis. Whyte (1998) argues that a group's collective efficacy, i.e. confidence in its abilities, can lead to reduced vigilance and a higher risk tolerance, similar to how groupthink was described.[56] McCauley (1998) proposes that the attractiveness of group members might be the most prominent factor in causing poor decisions.[57] Turner and Pratkanis (1991) suggest that from social identity perspective, groupthink can be seen as a group's attempt to ward off potentially negative views of the group.[6] Together, the contributions of these scholars have brought about new understandings of groupthink that help reformulate Janis' original model.

Sociocognitive theory[edit]

According to a theory many of the basic characteristics of groupthink – e.g., strong cohesion, indulgent atmosphere, and exclusive ethos – are the result of a special kind of mnemonic encoding (Tsoukalas, 2007). Members of tightly knit groups have a tendency to represent significant aspects of their community as episodic memories and this has a predictable influence on their group behavior and collective ideology, as opposed to what happens when they are encoded as semantic memories (which is common in formal and more loose group formations).[58]

See also[edit]

- Abilene paradox

- Amity-enmity complex

- Asch conformity experiments

- Bandwagon effect

- Collective intelligence

- Collective narcissism

- Democratic centralism

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Echo chamber (media)

- Emotional contagion

- False consensus effect

- Filter bubble

- Group flow

- Group polarization

- Group-serving bias

- Groupshift

- Herd behaviour

- Homophily

- In-group favoritism

- Individualism

- Lollapalooza effect

- Mass psychology

- Moral Man and Immoral Society

- No soap radio

- Mob rule

- Organizational dissent

- Positive psychology (relevantly, its criticism)

- Preference falsification

- Realistic conflict theory

- Risky shift

- Scapegoating

- Social comparison theory

- Solidarity

- Spiral of silence

- System justification

- Team error

- Tone policing

- Three men make a tiger

- Tuckman's stages of group development

- Vendor lock-in

- Wishful thinking

- Woozle effect

- Diversity

References[edit]

- ^ Leadership Glossary: Essential Terms for the 21st Century. 2015-06-18.

- ^ "Organisational behaviour - Docsity". www.docsity.com. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ^ "Groupthink". Ethics Unwrapped. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ^ a b c Turner, M. E.; Pratkanis, A. R. (1998). "Twenty-five years of groupthink theory and research: lessons from the evaluation of a theory" (PDF). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2–3): 105–115. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2756. PMID 9705798. S2CID 15074397. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-19.

- ^ Wexler, Mark N. (1995). "Expanding the groupthink explanation to the study of contemporary cults". Cultic Studies Journal. 12 (1): 49–71. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ^ a b Turner, M.; Pratkanis, A. (1998). "A social identity maintenance model of groupthink". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2–3): 210–235. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2757. PMID 9705803.

- ^ Sherman, Mark (March 2011), "Does liberal truly mean open-minded?", Psychology Today

- ^ Cain, Susan (January 13, 2012). "The rise of the new groupthink". New York Times..

- ^ a b Whyte, W. H. Jr. (March 1952). "Groupthink". Fortune. pp. 114–117, 142, 146.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Janis, I. L. (November 1971). "Groupthink" (PDF). Psychology Today. 5 (6): 43–46, 74–76. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d e Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink: a Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-14002-1.

- ^ a b c d e Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-31704-5.

- ^ 't Hart, P. (1998). "Preventing groupthink revisited: Evaluating and reforming groups in government". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2–3): 306–326. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2764. PMID 9705806.

- ^ a b McCauley, C. (1989). "The nature of social influence in groupthink: Compliance and internalization". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57 (2): 250–260. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.250.

- ^ Safire, William (August 8, 2004). "Groupthink". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

If the committee's other conclusions are as outdated as its etymology, we're all in trouble. 'Groupthink' (one word, no hyphen) was the title of an article in Fortune magazine in March 1952 by William H. Whyte Jr. ... Whyte derided the notion he argued was held by a trained elite of Washington's 'social engineers.'

- ^ Pol, O., Bridgman, T., & Cummings, S. (2022). The forgotten ‘immortalizer’: Recovering William H Whyte as the founder and future of groupthink research. Human Relations, 75(8): 1615-1641. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00187267211070680

- ^

Cross, Mary (2011-06-30). Bloggerati, Twitterati: How Blogs and Twitter are Transforming Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO (published 2011). p. 62. ISBN 9780313384844. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

[...] critics of twitter point to the predominance of the hive mind in such social media, the kind of groupthink that submerges independent thinking in favor of conformity to the group, the collective.

- ^

Taylor, Kathleen (2006-07-27). Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control. Oxford University Press (published 2006). p. 42. ISBN 9780199204786. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

[...] leaders often have beliefs which are very far from matching reality and which can become more extreme as they are encouraged by their followers. The predilection of many cult leaders for abstract, ambiguous, and therefore unchallengeable ideas can further reduce the likelihood of reality testing, while the intense milieu control exerted by cults over their members means that most of the reality available for testing is supplied by the group environment. This is seen in the phenomenon of 'groupthink', alleged to have occurred, notoriously, during the Bay of Pigs fiasco.

- ^

Jonathan I., Klein (2000). Corporate Failure by Design: Why Organizations are Built to Fail. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 145. ISBN 9781567202977. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

Groupthink by Compulsion [...] [G]roupthink at least implies voluntarism. When this fails, the organization is not above outright intimidation. [...] In [a nationwide telecommunications company], refusal by the new hires to cheer on command incurred consequences not unlike the indoctrination and brainwashing techniques associated with a Soviet-era gulag.

- ^ Cook K., The Theory of Groupthink Applied to Nanking, Stanford University, accessed 12 December 2020

- ^ a b Hart, Paul't (1991). "Irving L. Janis' "Victims of Groupthink"". Political Psychology. 12 (2): 247–278. doi:10.2307/3791464. JSTOR 3791464. S2CID 16128437.

- ^ Reaves, J. A. (2018). ".A Study of Groupthink in Project Teams". Available from ABI/INFORM Collection; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global Closed Collection. (2030111073).

- ^ Mok, Aurelia; Morris, Michael W. (November 2010). "An upside to bicultural identity conflict: Resisting groupthink in cultural ingroups". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 46 (6): 1114–1117. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.020. ISSN 0022-1031.

- ^ Tarmo, Crecencia Godfrey; Issa, Faisal H. (2021-01-01). "An analysis of groupthink and decision making in a collectivism culture: the case of a public organization in Tanzania". International Journal of Public Leadership. 18 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1108/IJPL-08-2020-0072. ISSN 2056-4929.

- ^ a b c d Aldag, R. J.; Fuller, S. R. (1993). "Beyond fiasco: A reappraisal of the groupthink phenomenon and a new model of group decision processes" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 113 (3): 533–552. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.533. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-18.

- ^ Aamodt, M. G. (2016). Group behavior, terms, and conflict. Industrial/organizational psychology: An applied approach (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- ^ Hartwig, R. (2007), Facilitating problem solving: A case study using the devil’s advocacy technique, Conference Papers - National Communication Association, published in Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal, Number 10, 2010, pp 17-32, accessed 2 November 2021

- ^ Fernandez, Claudia Plaisted (November 2007). "Creating Thought Diversity". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 13 (6): 670–671. doi:10.1097/01.phh.0000296146.09918.30. ISSN 1078-4659. PMID 17984724.

- ^ Cleary, Michelle; Lees, David; Sayers, Jan (2019-06-10). "Leadership, Thought Diversity, and the Influence of Groupthink". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 40 (8): 731–733. doi:10.1080/01612840.2019.1604050. ISSN 0161-2840. PMID 31180270.

- ^ Hong, Lu; Page, Scott E. (2004-11-08). "Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (46): 16385–16389. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403723101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 528939. PMID 15534225.

- ^ Edmondson, Amy C.; Lei, Zhike (2014-03-21). "Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct". Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 1 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305. ISSN 2327-0608.

- ^ Hirak, Reuven; Peng, Ann Chunyan; Carmeli, Abraham; Schaubroeck, John M. (February 2012). "Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures". The Leadership Quarterly. 23 (1): 107–117. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009. ISSN 1048-9843.

- ^ Edmondson, Amy C.; Higgins, Monica; Singer, Sara; Weiner, Jennie (2016-01-02). "Understanding Psychological Safety in Health Care and Education Organizations: A Comparative Perspective". Research in Human Development. 13 (1): 65–83. doi:10.1080/15427609.2016.1141280. ISSN 1542-7609.

- ^ Reaves, J. A. (2018). "A Study of Groupthink in Project Teams". Available from ABI/INFORM Collection; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global Closed Collection. (2030111073).

- ^ Harvey, Jerry B. (1974). "The abilene paradox: The management of agreement". Organizational Dynamics. 3 (1): 63–80. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(74)90005-9. ISSN 0090-2616.

- ^ "Gauging Group Dynamics". January 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Flowers, M.L. (1977). "A laboratory test of some implications of Janis's groupthink hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 35 (12): 888–896. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.12.888.

- ^ Schafer, M.; Crichlow, S. (1996). "Antecedents of groupthink: a quantitative study". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 40 (3): 415–435. doi:10.1177/0022002796040003002. S2CID 146163100.

- ^ Cline, R. J. W. (1990). "Detecting groupthink: Methods for observing the illusion of unanimity". Communication Quarterly. 38 (2): 112–126. doi:10.1080/01463379009369748.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Park, W.-W. (1990). "A review of research on groupthink" (PDF). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 3 (4): 229–245. doi:10.1002/bdm.3960030402. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-09.

- ^ Manz, C. C.; Sims, H. P. (1982). "The potential for "groupthink" in autonomous work groups". Human Relations. 35 (9): 773–784. doi:10.1177/001872678203500906. S2CID 145529591.

- ^ Fodor, Eugene M.; Smith, Terry, Jan 1982, The power motive as an influence on group decision making, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 42(1), 178–185. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.178

- ^ Callaway, Michael R.; Marriott, Richard G.; Esser, James K., Oct 1985, Effects of dominance on group decision making: Toward a stress-reduction explanation of groupthink, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 49(4), 949–952. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.49.4.949

- ^ Carrie, R. Leana (1985). A partial test of Janis' Groupthink Model: Effects of group cohesiveness and leader behavior on defective decision making, "Journal of Management", vol. 11(1), 5–18. doi: 10.1177/014920638501100102

- ^ Raven, B. H. (1998). "Groupthink: Bay of Pigs and Watergate reconsidered". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2/3): 352–361. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2766. PMID 9705808.

- ^ a b Badie, D. (2010). "Groupthink, Iraq, and the War on Terror: Explaining US policy shift toward Iraq". Foreign Policy Analysis. 6 (4): 277–296. doi:10.1111/j.1743-8594.2010.00113.x. S2CID 18013781.

- ^ "CW Communications: Comparison of AM and FMD. Middleton, Introduction to Statistical Communication Theory, McGraw Hill Book Company, New York, 1960 and, J. L. Lawson and G. E. Uhlenbeck, Threshold Signals, McGraw Hill Book Company, New York, 1950, contain extensive discussions of both AM and FM.", Communication Systems and Techniques, IEEE, 2009, doi:10.1109/9780470565292.ch3, ISBN 978-0-470-56529-2

- ^ Hart, Paul't (June 1991). "Irving L. Janis' Victims of Groupthink". Political Psychology. 12 (2): 247–278. doi:10.2307/3791464. ISSN 0162-895X. JSTOR 3791464.

- ^ "Recovery after Challenger", Space Shuttle Columbia, Springer Praxis Books in Space Exploration, Praxis, 2005, pp. 99–146, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-73972-4_3, ISBN 978-0-387-21517-4

- ^ a b c d Hermann, A.; Rammal, H. G. (2010). "The grounding of the "flying bank"". Management Decision. 48 (7): 1051. doi:10.1108/00251741011068761.

- ^ Eaton, Jack (2001). "Management communication: the threat of groupthink". Corporate Communications. 6 (4): 183–192. doi:10.1108/13563280110409791.

- ^ a b Koerber, C. P.; Neck, C. P. (2003). "Groupthink and sports: An application of Whyte's model". International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 15: 20–28. doi:10.1108/09596110310458954.

- ^ Baron, R. (2005). "So right it's wrong: Groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group decision making". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 37: 35. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(05)37004-3. ISBN 9780120152377.

- ^ a b c Kramer, R. M. (1998). "Revisiting the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam decisions 25 years later: How well has the groupthink hypothesis stood the test of time?". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2/3): 236–71. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2762. PMID 9705804.

- ^ Choi, Jin Nam; Kim, Myung Un (1999). "The organizational application of groupthink and its limitations in organizations". Journal of Applied Psychology. 84 (2): 297–306. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.2.297. ISSN 1939-1854.

Interestingly, several groupthink symptoms (i.e., group identity), such as the illusion of invulnerability, belief in inherent group morality, and illusion of unanimity, produced unexpected results: (a) negative correlations with concurrence seeking and defective decision making and (b) positive correlations with both internal and external team activities and with reported team performance.

- ^ Whyte, G. (1998). "Recasting Janis's Groupthink model: The key role of collective efficacy in decision fiascoes". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2/3): 185–209. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2761. PMID 9705802.

- ^ McCauley, C. (1998). "Group dynamics in Janis's theory of groupthink: Backward and forward". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2/3): 142–162. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2759. PMID 9705800.

- ^ Tsoukalas, I. (2007). "Exploring the microfoundations of group consciousness". Culture and Psychology. 13 (1): 39–81. doi:10.1177/1354067x07073650. S2CID 144625304.

Further reading[edit]

Articles[edit]

- Baron, R. S. (2005). "So right it's wrong: groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group decision making". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 37: 219–253. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37004-3. ISBN 9780120152377.

- Ferraris, C.; Carveth, R. (2003). "NASA and the Columbia disaster: Decision-making by groupthink?" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2003 Association for Business Communication Annual Convention. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- Esser, J. K. (1998). "Alive and well after 25 years: a review of groupthink research" (PDF). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 73 (2–3): 116–141. doi:10.1006/obhd.1998.2758. PMID 9705799. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-18.

- Hogg, M. A.; Hains, S. C. (1998). "Friendship and group identification: A new look at the role of cohesiveness in groupthink". European Journal of Social Psychology. 28 (3): 323–341. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199805/06)28:3<323::AID-EJSP854>3.0.CO;2-Y.

- Klein, D. B.; Stern, C. (Spring 2009). "Groupthink in academia: Majoritarian departmental politics and the professional pyramid". The Independent Review: A Journal of Political Economy (Independent Institute). 13 (4): 585–600.

- Mullen, B.; Anthony, T.; Salas, E.; Driskell, J. E. (1994). "Group cohesiveness and quality of decision making: An integration of tests of the groupthink hypothesis". Small Group Research. 25 (2): 189–204. doi:10.1177/1046496494252003. S2CID 143659013.

- Moorhead, G.; Ference, R.; Neck, C. P. (1991). "Group decision fiascoes continue: Space Shuttle Challenger and a revised groupthink framework" (PDF). Human Relations. 44 (6): 539–550. doi:10.1177/001872679104400601. S2CID 145804327. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-07.

- O'Connor, M. A. (Summer 2003). "The Enron board: The perils of groupthink". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 71 (4): 1233–1320. SSRN 1791848.

- Packer, D. J. (2009). "Avoiding groupthink: Whereas weakly identified members remain silent, strongly identified members dissent about collective problems" (PDF). Psychological Science. 20 (5): 546–548. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02333.x. PMID 19389133. S2CID 26310448.

- Rose, J. D. (Spring 2011). "Diverse perspectives on the groupthink theory: A literary review" (PDF). Emerging Leadership Journeys. 4 (1): 37–57.

- Tetlock, P. E. (1979). "Identifying victims of groupthink from public statements of decision makers" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37 (8): 1314–1324. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.8.1314.

- Tetlock, P. E.; Peterson, R. S.; McGuire, C.; Chang, S. J.; Feld, P. (1992). "Assessing political group dynamics: A test of the groupthink model" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 63 (3): 403–425. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.403.

- Turner, M. E.; Pratkanis, A. R.; Probasco, P.; Leve, C. (1992). "Threat, cohesion, and group effectiveness: Testing a social identity maintenance perspective on groupthink" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 63 (5): 781–796. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.5.781. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-23. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- Whyte, G. (1989). "Groupthink reconsidered". Academy of Management Review. 14 (1): 40–56. doi:10.2307/258190. JSTOR 258190.

Books[edit]

- Janis, Irving L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-14002-1.

- Janis, Irving L.; Mann, L. (1977). Decision making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-916190-8.

- Kowert, P. (2002). Groupthink or Deadlock: When do Leaders Learn from their Advisors?. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5250-6.

- Martin, Everett Dean, The Behavior of Crowds, A Psychological Study, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1920.

- Nemeth, Charlan (2018). In Defense of Troublemakers: The Power of Dissent in Life and Business. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465096299.

- Schafer, M.; Crichlow, S. (2010). Groupthink versus High-Quality Decision Making in International Relations. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14888-7.

- Sunstein, Cass R.; Hastie, Reid (2014). Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter. Harvard Business Review Press.

- 't Hart, P. (1990). Groupthink in Government: a Study of Small Groups and Policy Failure. Amsterdam; Rockland, MA: Swets & Zeitlinger. ISBN 90-265-1113-2.

- 't Hart, P.; Stern, E. K.; Sundelius, B. (1997). Beyond Groupthink: Political Group Dynamics and Foreign Policy-Making. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-09653-2.