History of the Ryukyu Islands

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

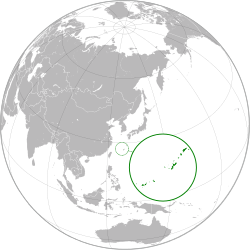

This article is about the history of the Ryukyu Islands southwest of the main islands of Japan.

| History of Ryukyu |

|---|

|

Etymology[edit]

The name "Ryūkyū" originates from Chinese writings.[1][2] The earliest references to "Ryūkyū" write the name as 琉虬 and 流求 (pinyin: Liúqiú; Jyutping: Lau4kau4) in the Chinese history Book of Sui in 607. It is a descriptive name, meaning "glazed horn-dragon".

The origin of the term "Okinawa" remains unclear, although "Okinawa" (Okinawan: Uchinaa) as a term was used in Okinawa. There was also a divine woman named "Uchinaa" in the book Omoro Sōshi, a compilation of ancient poems and songs from Okinawa Island. This suggests the presence of a divine place named Okinawa. The Chinese monk Jianzhen, who traveled to Japan in the mid-8th century CE to promote Buddhism, wrote "Okinawa" as 阿児奈波 (anjenaʒpa).[3] The Japanese map series Ryukyu Kuniezu labeled the island as 悪鬼納 (Wokinaha) in 1644. The current Chinese characters (kanji) for Okinawa (沖縄) were first written in the 1702 version of Ryukyu Kuniezu.

Early history[edit]

Prehistoric period[edit]

The ancestry of the modern-day Ryukyuan people is disputed. One theory claims that the earliest inhabitants of these islands crossed a prehistoric land bridge from modern-day China, with later additions of Austronesians, Micronesians, and Japanese merging with the population.[4] The time when human beings appeared in Okinawa remains unknown. The earliest human bones were those of Yamashita Cave Man, about 32,000 years ago, followed by Pinza-Abu Cave Man, Miyakojima, about 26,000 years ago and Minatogawa Man, about 18,000 years ago. They probably came through China and were once considered to be the direct ancestors of those living in Okinawa. No stone tools were discovered with them. For the following 12 000 years, no trace of archaeological sites was discovered after the Minatogawa man site.[citation needed][5]

Okinawa midden culture[edit]

Okinawa midden culture or shell heap culture is divided into the early shell heap period corresponding to the Jōmon period of Japan and the latter shell heap period corresponding to the Yayoi period of Japan. However, the use of Jōmon and Yayoi of Japan is questionable in Okinawa. In the former, it was a hunter-gatherer society, with wave-like opening Jōmon pottery. In the latter part of Jōmon period, archaeological sites moved near the seashore, suggesting the engagement of people in fishery. In Okinawa, rice was not cultivated during the Yayoi period but began during the latter period of shell-heap age. Shell rings for arms made of shells obtained in the Sakishima Islands, namely Miyakojima and Yaeyama islands, were imported by Japan. In these islands, the presence of shell axes, 2500 years ago, suggests the influence of a southeastern-Pacific culture.[citation needed][6][7]

Mythology, the Shunten Dynasty and the Eiso Dynasty[edit]

The first history of Ryukyu was written in Chūzan Seikan ("Mirrors of Chūzan"), which was compiled by Shō Shōken (1617–75), also known as Haneji Chōshū. The Ryukyuan creation myth is told, which includes the establishment of Tenson as the first king of the islands and the creation of the Noro, female priestesses of the Ryukyuan religion. The throne was usurped from one of Tenson's descendants by a man named Riyu. Chūzan Seikan then tells the story of a Japanese samurai, Minamoto no Tametomo (1139–70), who fought in the Hogen Rebellion of 1156 and fled first to Izu Island and then to Okinawa. He had relations with the sister of the Aji of Ōzato and sired Shunten, who then led a popular rebellion against Riyu and established his own rule at Urasoe Castle. Most historians, however, discount the Tametomo story as a revisionist history that is intended to legitimize Japanese domination over Okinawa.[8] Shunten's dynasty ended in the third generation when his grandson, Gihon, abdicated, went into exile, and was succeeded by Eiso, who began a new royal lineage. The Eiso dynasty continued for five generations.

Gusuku period[edit]

Gusuku is the term used for the distinctive Okinawan form of castles or fortresses. Many gusukus and related cultural remains in the Ryukyu Islands have been listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites under the title Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu. After the midden culture, agriculture started about the 12th century, with the center moving from the seashore to higher places. This period is called the gusuku period. There are three perspectives regarding the nature of gusukus: 1) a holy place, 2) dwellings encircled by stones, 3) a castle of a leader of people. In this period, porcelain trade between Okinawa and other countries became busy, and Okinawa became an important relay point in eastern-Asian trade. Ryukyuan kings, such as Shunten and Eiso, were considered to be important governors. In 1272, Kublai Khan ordered Ryukyu to submit to Mongol suzerainty, but King Eiso refused. In 1276, the Mongol envoys returned, but were driven off the island by the Ryukyuans.[9]

Three-Kingdom period[edit]

The Three-Kingdom period, also known as the Sanzan period (三山時代, Sanzan-jidai) (Three Mountains), lasted from 1322 until 1429. There was a gradual consolidation of power under the Shō family. Shō Hashi (1372–1439) conquered Chūzan, the middle kingdom, in 1404 and made his father, Shō Shishō, the king. He conquered Hokuzan, the northern kingdom, in 1416 and conquered the southern kingdom, Nanzan, in 1429, thereby unifying the three kingdoms into a single Ryukyu Kingdom.[citation needed] Shō Hashi was then recognized as the ruler of the Ryukyu Kingdom (or Liuqiu Kingdom in Chinese) by the Ming dynasty Emperor of China, who presented him a red lacquerware plaque known as the Chūzan Tablet.[10] Although independent, the kings of the Ryukyu Kingdom paid tribute to the rulers of China.

Ryukyu Kingdom[edit]

Ryukyu Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1429–1879 | |||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Ishinagu nu uta" (石投子之歌)[11] | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Shuri | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ryukyuan (native languages), Classical Chinese, Classical Japanese | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups | Ryukyuan | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Ryukyuan religion, Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| King (國王) | |||||||||||||||||

• 1429–1439 | Shō Hashi | ||||||||||||||||

• 1477–1526 | Shō Shin | ||||||||||||||||

• 1587–1620 | Shō Nei | ||||||||||||||||

• 1848–1879 | Shō Tai | ||||||||||||||||

| Sessei (摂政) | |||||||||||||||||

• 1666–1673 | Shō Shōken | ||||||||||||||||

| Regent (國師) | |||||||||||||||||

• 1751–1752 | Sai On (Sai Un) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Shuri cabinet (首里王府), Sanshikan (三司官) | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Unification | 1429 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 April 1609 | |||||||||||||||||

• Reorganized into Ryukyu Domain | 1872 | ||||||||||||||||

| 27 March 1879 | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Ryukyuan, Chinese, and Japanese mon coins[12] | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Japan | ||||||||||||||||

1429–1609[edit]

In 1429 King Shō Hashi completed the unification of the three kingdoms and founded a single Ryukyu Kingdom with its capital at Shuri Castle.[citation needed] Shō Shin (尚真) (1465–1526; r. 1477–1526) became the third king of the Second Sho Dynasty - his reign has been described[by whom?] as the "Great Days of Chūzan", a period of great peace and relative prosperity. He was the son of Shō En, the founder of the dynasty, by Yosoidon, Shō En's second wife, often referred to as the queen-mother. He succeeded his uncle, Shō Sen'i, who was forced[by whom?] to abdicate in his favor. Much of the foundational organization of the kingdom's administration and economy stemmed from developments which occurred during Shō Shin's reign. The reign of Shō Shin also saw the expansion of the kingdom's control over several of the outlying Ryukyu Islands, such as Miyako-jima and Ishigaki Island.[citation needed]

Many Chinese moved to Ryukyu to serve the government or to engage in business during this period. In 1392, during the Hongwu Emperor's reign, the Ming dynasty Chinese had sent 36 Chinese families from Fujian at the request of the Ryukyuan King to manage oceanic dealings in the kingdom. Many Ryukyuan officials descended from these Chinese immigrants, being born in China or having Chinese grandfathers.[13] They assisted the Ryukyuans in advancing their technology and diplomatic relations.[14][15][16]

Satsuma domination, 1609–1871[edit]

The invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom by the Shimazu clan of Japan's Satsuma Domain took place in April 1609. Three thousand men and more than one hundred war-junks sailed from Kagoshima at the southern tip of Kyushu. The invaders defeated the Ryukyuans in the Amami Islands, then at Nakijin Castle on Okinawa Island. The Satsuma samurai made a second landing near Yomitanzan and marched overland to Urasoe Castle, which they captured. Their war-junks attempted to take the port city of Naha, but were defeated by the Ryūkyūan coastal defences. Finally Satsuma captured Shuri Castle,[17] the Ryukyuan capital, and King Shō Nei. Only at this point did the King famously tell his army that "nuchidu takara" (life is a treasure), and they surrendered.[18] Many priceless cultural treasures were looted and taken to Kagoshima. As a result of the war, the Amami Islands were ceded to Satsuma in 1611; the direct rule of Satsuma over the Amami Islands started in 1613.

After 1609 the Ryukyuan kings became vassals of Satsuma. Though recognized as an independent kingdom,[19] the islands were occasionally also referred to[by whom?] as being a province of Japan.[20] The Shimazu introduced a policy banning sword ownership by commoners. This led to the development of the indigenous Okinawan martial arts, which utilize domestic items as weapons.[citation needed] This period of effective outside control also featured the first international matches of Go, as Ryukyuan players came to Japan to test their skill. This occurred in 1634, 1682, and 1710.[21][22]

In the 17th century the Ryukyu kingdom thus became both a tributary of China and a vassal of Japan. Because China would not make a formal trade agreement unless a country was a tributary state, the kingdom served as a convenient loophole for Japanese trade with China. When Japan officially closed foreign trade, the only exceptions for foreign trade were with the Dutch through Nagasaki, with the Ryukyu Kingdom through the Satsuma Domain, and with Korea through Tsushima.[23] Perry's "Black Ships", official envoys from the United States, came in 1853.[24] In 1871, the Mudan incident occurred, in which fifty-four Ryukyuans were killed in Taiwan. They had wandered into the central part of Taiwan after their ship was wrecked.

Ryukyu Domain, 1872–1879[edit]

In 1872 the Ryukyu Kingdom was reconfigured as a feudal domain (han).[25] The people were described[by whom?] as appearing to be a "connecting link" between the Chinese and Japanese.[26] After the Taiwan Expedition of 1874, Japan's role as the protector of the Ryukyuan people was acknowledged[by whom?]; but the fiction of the Ryukyu Kingdom's independence was partially maintained until 1879.[27] In 1878 the islands were listed as a "tributary" to Japan. The largest island was listed as "Tsju San", meaning "middle island". Others were listed as Sannan in the south and Sanbok in the North Nawa. The main port was listed as "Tsju San". It was open to foreign trade.[26] Agricultural produce included tea, rice, sugar, tobacco, camphor, fruits, and silk. Manufactured products included cotton, paper, porcelain, and lacquered ware.[26]

Okinawa Prefecture, 1879–1937[edit]

In 1879, Japan declared its intention to annex the Ryukyu Kingdom. China protested and asked former U.S. President Ulysses Grant, then on a diplomatic tour of Asia, to intercede. One option considered involved Japan annexing the islands from Amami Island north, China annexing the Miyako and Yaeyama islands, and the central islands remaining an independent Ryukyu Kingdom. When the negotiation eventually failed, Japan annexed the entire Ryukyu archipelago.[28] Thus, the Ryukyu han was abolished and replaced by Okinawa Prefecture by the Meiji government. The monarchy in Shuri was abolished and the deposed king Shō Tai (1843–1901) was forced to relocate to Tokyo. In compensation, he was made a marquis in the Meiji system of peerage.[29]

Hostility against mainland Japan increased in the Ryukyus immediately after its annexation to Japan in part because of the systematic attempt on the part of mainland Japan to eliminate the Ryukyuan culture, including the language, religion, and cultural practices. Japan introduced public education that permitted only the use of standard Japanese while shaming students who used their own language by forcing them to wear plaques around their necks proclaiming them "dialect speakers". This increased the number of Japanese language speakers on the islands, creating a link with the mainland. When Japan became the dominant power of the Far East, many Ryukyuans were proud of being citizens of the Empire. However, there was always an undercurrent of dissatisfaction for being treated as second class citizens.[citation needed]

Okinawa and World War II[edit]

In the years leading up to World War II, the Japanese government sought to reinforce national solidarity in the interests of militarization. In part, they did so by means of conscription, mobilization, and nationalistic propaganda. Many of the people of the Ryukyu Islands, despite having spent only a generation as full Japanese citizens, were interested in proving their value to Japan in spite of prejudice expressed by mainland Japanese people.[30]

In 1943, during World War II, the US president asked its ally, the Republic of China, if it would lay claim to the Ryukyus after the war.[31] "The President then referred to the question of the Ryukyu Islands and enquired more than once whether China would want the Ryukyus. The Generalissimo replied that China would be agreeable to joint occupation of the Ryukyus by China and the United States and, eventually, joint administration by the two countries under the trusteeship of an international organization."[32] On March 23, 1945, the United States began its attack on the island of Okinawa, the final outlying islands, prior to the expected invasion of mainland Japan.

Battle of Okinawa: April 1 – June 22, 1945[edit]

The Battle of Okinawa was one of the last major battles of World War II,[33] claiming the lives of an estimated 120,000 combatants. The Ryukyus were the only inhabited part of Japan to experience a land battle during World War II. In addition to the Japanese military personnel who died in the Battle for Okinawa, well over one third of the civilian population, which numbered approximately 300,000 people, were killed. Many important documents, artifacts, and sites related to Ryukyuan history and culture were also destroyed, including the royal Shuri Castle.[34] Americans had expected the Okinawan people to welcome them as liberators but the Japanese had used propaganda to make the Okinawans fearful of Americans. As a result, some Okinawans joined militias and fought along Japanese. This was a major cause of the civilian casualties, as Americans could not distinguish between combatants and civilians.[citation needed]

Due to fears concerning their fate during and after the invasion, the Okinawan people hid in caves and in family tombs. Several mass deaths occurred, such as in the "Cave of the Virgins", where many Okinawan school girls committed suicide by jumping off cliffs for fear of rape. Similarly, whole families committed suicide or were killed by near relatives in order to avoid suffering what they believed would be a worse fate at the hands of American forces; for instance, on Zamami Island at Zamami Village, almost everyone living on the island committed suicide two days after Americans landed.[35] The Americans had made plans to safeguard the Okinawans;[36] their fears were not unfounded, as killing of civilians and destruction of civilian property did take place; for example, on Aguni Island, 90 residents were killed and 150 houses were destroyed.[37]

As the fighting intensified, Japanese soldiers hid in caves with civilians, further increasing civilian casualties. Additionally, Japanese soldiers shot Okinawans who attempted to surrender to Allied Forces. America utilized Nisei Okinawans in psychological warfare, broadcasting in Okinawan, leading to the Japanese belief that Okinawans who did not speak Japanese were spies or disloyal to Japan, or both. These people were often killed as a result. As food became scarce, some civilians were killed over small amounts of food. "At midnight, soldiers would wake up Okinawans and take them to the beach. Then they chose Okinawans at random and threw hand grenades at them."[attribution needed][38]

Massive casualties in the Yaeyama Islands caused the Japanese military to force people to evacuate from their towns to the mountains, even though malaria was prevalent there. Fifty-four percent of the island's population died due to starvation and disease. Later, islanders unsuccessfully sued the Japanese government. Many military historians believe that the ferocity of the Battle of Okinawa led directly to the American decision to use the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A prominent holder of this view is Victor Davis Hanson, who states it explicitly in his book Ripples of Battle: "because the Japanese on Okinawa, including native Okinawans, were so fierce in their defense (even when cut off, and without supplies), and because casualties were so appalling, many American strategists looked for an alternative means to subdue mainland Japan, other than a direct invasion."[39]

Princess Lilies[edit]

After the beginning of World War II, the Japanese military conscripted school girls (15 to 16 years old) to join a group known as the Princess Lilies (Hime-yuri) and to go to the battle front as nurses. There were seven girls' high schools in Okinawa at the time of World War II. The board of education, made up entirely of mainland Japanese, required the girls' participation. The Princess Lilies were organized at two of them, and a total of 297 students and teachers eventually joined the group. Teachers, who insisted that the students be evacuated to somewhere safe, were accused of being traitors.[citation needed]

Most of the girls were put into temporary clinics in caves to take care of injured soldiers. With a severe shortage of food, water and medicine, 211 of the girls died while trying to care for the wounded soldiers.[citation needed] The Japanese military had told these girls that, if they were taken as prisoners, the enemy would rape and kill them; the military gave hand grenades to the girls to allow them to commit suicide rather than be taken as prisoners. One of the Princess Lilies explained: "We had a strict imperial education, so being taken prisoner was the same as being a traitor. We were taught to prefer suicide to becoming a captive."[38] Many students died saying, "Tennō Heika Banzai", which means "Long live the Emperor".

Post-war occupation[edit]

After the war, the islands were occupied by the United States and were initially governed by the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands from 1945 to 1950 when it was replaced by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands from 1950 which also established the Government of the Ryukyu Islands in 1952. The Treaty of San Francisco which went into effect in 1952, officially ended wartime hostilities. However, ever since the battle of Okinawa, the presence of permanent American bases has created friction between Okinawans and the U.S. military. During the occupation, American military personnel were exempt from domestic jurisdiction since Okinawa was an occupied territory of the United States.

Effective U.S. control continued even after the end of the occupation of Japan as a whole in 1952. The United States dollar was the official currency used, and cars drove on the right, American-style, as opposed to on the left as in Japan. The islands switched to driving on the left in 1978, six years after they were returned to Japanese control. The U.S. used their time as occupiers to build large army, air force, navy, and marine bases on Okinawa.

On November 21, 1969, a Joint Communique was issued by President Nixon and Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, with the US president agreeing to return the Ryukyus to Japan in 1972. U.S. President Richard Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Satō later signed the Okinawa Reversion Agreement in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1971.[40] The U.S. reverted the islands to Japan on May 15, 1972, setting back a Ryūkyū independence movement that had emerged. Under terms of the agreement, the U.S. retained its rights to bases on the island as part of the 1952 Treaty to protect Japan, but those bases were to be nuclear-free. The United States military still controls about 19% of the island, making the 30,000 American servicemen a dominant feature in island life. While the Americans provide jobs to the locals on base, and in tourist venues, and pay rent on the land, widespread personal relationships between U.S. servicemen and Okinawan women remain controversial in Okinawan society. Okinawa remains Japan's poorest prefecture.

Agent Orange controversy[edit]

Evidence suggests that the US military's Project 112 tested biochemical agents on US marines in Okinawa in the 1960s.[41] Later, suggestions were made that the US may have stored and used Agent Orange at its bases and training areas on the island.[42][43] In at least one location where Agent Orange was reportedly used, there have been incidences of leukemia among locals, one of the listed effects of Agent Orange exposure. Drums that were unearthed in 2002 in one of the reported disposal locations were seized by the Okinawa Defense Bureau, an agency of Japan's Ministry of Defense, which has not issued a report on what the drums contained.[44] The United States denies that Agent Orange was ever present on Okinawa.[45] Thirty US military veterans claim that they saw Agent Orange on the island. Three of them have been awarded related disability benefits by the US Veteran's administration. The locations of suspected Agent Orange contamination include Naha port, Higashi, Camp Schwab, and Chatan.[46][47] In May 2012, it was claimed that the US transport ship USNS Schuyler Otis Bland (T-AK-277) had transported herbicides to Okinawa on 25 April 1962. The defoliant might have been tested in Okinawa's northern area between Kunigami and Higashi by the US Army's 267th Chemical Service Platoon to assess its potential usefulness in Vietnam.[48] A retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel, Kris Roberts, told The Japan Times that his base maintenance team unearthed leaking barrels of unknown chemicals at Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in 1981.[49] In 2012 a US Army environmental assessment report, published in 2003, was discovered which stated that 25,000 55-gallon drums of Agent Orange had been stored on Okinawa before being taken to Johnston Atoll for disposal.[50] In February 2013, an internal US DoD investigation concluded that no Agent Orange had been transported to, stored, or used on Okinawa. No veterans or former base workers were interviewed for the investigation.[51]

Prosecution under Status of Forces Agreement[edit]

After Okinawa reunited with Japan in 1972, Japan immediately signed a treaty with the U.S. so that the American military could stay in Okinawa. The legal agreement remained the same. If American military personnel were accused of a crime in Okinawa, the US military retained jurisdiction to try them as part of the U.S.–Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) if the victim were another American or if the offense were committed during the execution of official duties. This is routine for military service people stationed in foreign countries.

In 1995, two Marines and a sailor kidnapped and raped a 12-year-old girl, and, under the SOFA with the U.S., local police and prosecutors were unable to get access to the troops until they were able to prepare an indictment. What angered many Okinawans in this instance was that the suspects were not handed over to Japanese police until after they had been formally indicted in an Okinawan court, although they were apprehended by American military law enforcement authorities the day after the rape and confined in a navy brig until then.[citation needed] In the Michael Brown Okinawa assault incident, a US Marine officer was convicted of attempted indecent assault and destruction of private property involving a local resident of Filipino descent who worked at Camp Courtney.[52]

In February, 2008, a U.S. Marine was arrested for allegedly raping a 14-year-old Japanese girl in Okinawa,[53] and a member of the U.S. Army was suspected of raping a Filipino woman in Okinawa.[54] U.S. Ambassador Thomas Schieffer flew to Okinawa and met with Okinawa governor Hirokazu Nakaima to express U.S. concern over the cases and offer cooperation in the investigation.[55] U.S. Forces Japan designated February 22 as a Day of Reflection for all U.S. military facilities in Japan, setting up a Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Task Force in an effort to prevent similar incidents.[56]

Planned development of American bases[edit]

Base-related revenue makes up 5% of the total economy. If the U.S. vacated the land, it is claimed[who?] that the island would be able to generate more money from tourism by the increased land available for development.[57] In the 1990s, a Special Actions Committee was set up to prepare measures to ease tensions, most notably the return of approximately 50 square kilometres (19 sq mi) to the Japanese state.[citation needed]

Other complaints are that the military bases disrupt the lives of the Okinawan people; the American military occupy more than a fifth of the main island. The biggest and most active air force base in east Asia, Kadena Air Base, is based on the island; the islanders complain the base produces large amounts of noise and is dangerous in other ways. In 1959 a jet fighter crashed into a school on the island, killing 17 children and injuring 121. On August 13, 2004, a U.S. military helicopter crashed into Okinawa International University, injuring the three crew members on board. The U.S. military arrived on scene first then physically barred local police from participating in the investigation of the crash. The US did not allow local authorities to examine the scene until six days after the crash.[58][59][60][61][62] In a similar manner, unexploded ordnance from WWII continues to be a danger, especially in sparsely-populated areas where it may have lain undisturbed or been buried.[63]

Notable people[edit]

- Isamu Chō was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army known for his support of ultranationalist politics and involvement in a number of attempted military and right-wing coup d'etats in pre-World War II Japan.

- Takuji Iwasaki was a Japanese meteorologist, biologist, ethnologist historian.

- Uechi Kanbun was the founder of Uechi-ryū, one of the primary karate styles of Okinawa.

- Ōta Minoru was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, and the final commander of the Japanese naval forces defending the Oroku Peninsula during the Battle of Okinawa.

- Akira Shimada was a governor of Okinawa Prefecture. He was sent to Okinawa in 1945 and died in the battle.

- Mitsuru Ushijima was the Japanese general at the Battle of Okinawa, during the final stages of World War II.

- Kentsū Yabu was a prominent teacher of Shōrin-ryū karate in Okinawa from the 1910s until the 1930s, and was among the first people to demonstrate karate in Hawaii.

- Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., an American Lieutenant-General, was killed during the closing days of the Battle of Okinawa by enemy artillery fire, making him the highest-ranking US military officer to have been killed by enemy fire during World War II.

- Ernest Taylor Pyle was an American journalist who wrote as a roving correspondent for the Scripps Howard newspaper chain from 1935 until his death in combat during World War II. He died in Ie Jima, Okinawa.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Minamijima Fudoki Chimei-gaisetsu Okinawa, Higashionna Kanjun, p.16 in Japanese

- ^ The transition of Okinawa and Ryukyu Ryukyu-Shimpo-Sha, 2007, in Japanese

- ^ http://lodel.ehess.fr/crlao/docannexe.php?id=1227 [bare URL]

- ^ An Austronesian Presence in Southern Japan: Early Occupation in the Yaeyama Islands Archived February 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Glenn R. Summerhayes and Atholl Anderson, Department of Anthropology, Otago University, retrieved November 22, 2009

- ^ Toshiaki, Arashiro (2001), High School History of Ryukyu, Okinawa, Toyo Kikaku, pp. 10–11, ISBN 4-938984-17-2 in which 3 more sites in Okinawa are described. Coral islands favor the preservation of olden human bones.

- ^ Toshiaki 2001, pp. 12, 20.

- ^ Ito, Masami, "Between a rock and a hard place", Japan Times, May 12, 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Tze May Loo, Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa's Incorporation into Modern Japan (New York: Lexington Books, 2014), 94-96.

- ^ George H. Kerr, Okinawa: History of an Island People (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1958), 51.

- ^ Kerr, George (October 2000). Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0-80482087-5.

- ^ Arben Anthony Saavedra, Fernando Inafuku (April 21, 2019). National Anthem of the Ryukyu Kingdom 琉球王国国歌 (YouTube) (in Okinawan). Okinawa. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Ryuukyuuan coins". Luke Roberts at the Department of History – University of California at Santa Barbara. 24 October 2003. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The eunuchs in the Ming dynasty (ill. ed.). SUNY Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-7914-2687-4. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Schottenhammer, Angela (2007). Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The East Asian maritime world 1400–1800: its fabrics of power and dynamics of exchanges. East Asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East Asian maritime history. Vol. 4 (ill. ed.). Otto Harrassowitz. p. xiii. ISBN 978-3-447-05474-4. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Gang Deng (1999). Maritime sector, institutions, and sea power of premodern China. Contributions in economics and economic history. Vol. 212 (ill. ed.). Greenwood. p. 125. ISBN 0-313-30712-1. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Hendrickx, Katrien (2007). The Origins of Banana-fibre Cloth in the Ryukyus, Japan (ill. ed.). Leuven University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-90-5867-614-6. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ Okinawa Prefectural reserve cultural assets center (2015). "首里城跡". sitereports.nabunken.go.jp. Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. The Samurai Capture a King: Okinawa 1609. 2009.

- ^ Smits, Gregory (1999). Visions of Ryūkyū: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics, p. 28.

- ^ Toby, Ronald P. (1991). State and Diplomacy in Early Modern Japan: Asia and the development of the Tokugawa bakufu, pp. 45–46, citing manuscripts at the Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo: "Ieyasu granted the Shimazu clan the right to "rule" over Ryukyu… [and] contemporary Japanese even referred to the Shimazu clan as 'lords of four provinces', which could only mean that they were including the Ryukyu Kingdom in their calculations. However, this does not mean that Ryūkyū ceased to be a foreign country or that relations between Naha and Edo ceased thereby to be foreign relations."

- ^ Sensei's Library: Ryukyuan players

- ^ Go – Feature: Go in old Okinawa, MindZine Archived March 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hamashita Takeshi, "The Intra-Regional System in East Asia in Modern Times", in Network Power: Japan and Asia, ed. P. Katzenstein & T. Shiraishi (1997), 115.

- ^ "Okinawa, Commodore Perry, and the Lew Chew Raid". III publishing (World wide web log). March 8, 2010.

- ^ Lin, Man-houng. "The Ryukyus and Taiwan in the East Asian Seas: A Longue Durée Perspective," Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. October 27, 2006, transl. & abridged from Academia Sinica Weekly, No. 1084. August 24, 2006.

- ^ a b c Ross/Globe Vol. IV: Loo-Choo, 1878.

- ^ Goodenough, Ward H. GEORGE H. KERR. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Pp. xviii, 542. Rut land, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1958. $6.75 Book Review: "George H. Kerr. Okinawa: the History of an Island People…," The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, May 1959, Vol. 323, No. 1, p. 165.

- ^ The Demise of the Ryukyu Kingdom: Western Accounts and Controversy. Ed by Eitetsu Yamagushi and Yoko Arakawa. Ginowan-City, Okinawa: Yonushorin, 2002.

- ^ Papinot, Edmond. (2003). Nobiliare du Japon – Sho, p. 56 (PDF@60); Papinot, Jacques Edmond Joseph. (1906). Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie du Japon. retrieved 2012-11-7.

- ^ Kerr pp. 459–64

- ^ Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943 p. 324 Chinese Summary Record.

- ^ "Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, The Conferences at Cairo and Tehran, 1943 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Okinawa Prefectural reserve cultural assets center (2015). "沖縄県の戦争遺跡". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ The Age of Shuri Castle, Wonder Okinawa.

- ^ Geruma Island[permanent dead link], Wonder Okinawa.

- ^ Appleman, Roy E. (2000) [1948]. "Chapter I: Operation Iceberg". Okinawa:The Last Battle. The United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-11. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Aguni Island Archived November 13, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Wonder Okinawa.

- ^ a b Moriguchi, 1992.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis, (October 12, 2004). "Ripples of Battle: How Wars of the Past Still Determine How We Fight, How We Live, and How We Think", Anchor, October 12, 2004, ISBN 978-0-38572194-3

- ^ "Wwma.net".

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "'Were we marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?'", Japan Times, 4 December 2012, p. 14

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Evidence for Agent Orange on Okinawa", Japan Times, April 12, 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Agent Orange buried at beach strip?", Japan Times, 30 November 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Agent Orange buried on Okinawa, vet says", Japan Times, August 13, 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Okinawa vet blames cancer on defoliant", Japan Times, August 24, 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Vets win payouts over Agent Orange use on Okinawa Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 14 February 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "U.S. vet pries lid off Agent Orange denials", Japan Times, 15 April 2012.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Agent Orange 'tested in Okinawa'", Japan Times, 17 May 2012, p. 3

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "Agent Orange at base in '80s: U.S. vet", Japan Times, 15 June 2012, p. 1

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "25,000 barrels of Agent Orange kept on Okinawa, U.S. Army document says", Japan Times, 7 August 2012, p. 12

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "As evidence of Agent Orange in Okinawa stacks up, U.S. sticks with blanket denial", Japan Times, 4 June 2013, p. 13

- ^ Selden, Mark (July 13, 2004). "Marine Major Convicted of Molestation on Okinawa". Znet. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ "Anger spreads through Okinawa", The Japan Times, Feb. 14, 2008

- ^ Japan probes new allegations of rape linked to U.S. military, CNN.com Asia, February 20, 2008

- ^ "U.S. envoy visits Okinawa" Archived February 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, CNN.com Asia, February 13, 2008

- ^ "U.S. imposes curfew on Okinawa forces", The Japan Times, February 21, 2008

- ^ Mitchell, Jon, "What awaits Okinawa 40 years after reversion? Archived July 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 13 May 2012, p. 7

- ^ "No Fly Zone English Home". noflyzone.homestead.com.

- ^ ZNet |Japan|Anger Explodes as a U.S. Army Helicopter Crash at Okinawa International University Archived May 8, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carol, Joe, "Futenma divides Okinawa's expats" Japan Times, June 8, 2010.

- ^ Kyodo News, "Bad memories of U.S. bases linger", Japan Times, April 29, 2010.

- ^ Takahara, Kanako, "Missing pin caused copter crash: report", Japan Times, October 6, 2004.

- ^ MACHINAMI : Ie Island

References[edit]

- Appleman, Roy E. et al. (1947), Okinawa: The Last Battle Archived November 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (LOC 49–45742), the 1945 battle

- Feifer, George (1992), Tennozan (ISBN 0-395-70066-3)

- Kerr, George H. (1958). Okinawa: the History of an Island People. Rutland, VT: Charles Tuttle. OCLC 722356

- ––– (1953). Ryukyu Kingdom and Province before 1945. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council. OCLC 5455582

- Matsuda, Mitsugu (2001), Ryūkyū ōtō-shi 1609–1872-nen 琉球王統史 1609-1872年 [The Government of the Kingdom of Ryukyu, 1609–1872] (in Japanese, ISBN 4-946539-16-6).

- Rabson, Steve (1996), Assimilation Policy in Okinawa: Promotion, Resistance, and "Reconstruction" Archived June 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Japan Policy Research Institute.

- Ross, J.M. ed. (1878). "Globe Encyclopaedia of Universal Information", Vol. IV, Edinburgh-Scotland, Thomas C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works, retrieved from Google Books 2009-03-18;

- Toshiaki, Arashiro (2001). Kōtō gakkō Ryūkyū Okinawa-shi 高等学校琉球・沖縄史 [High School History of Ryukyu and Okinawa], Toyokikaku (in Japanese, ISBN 4-938984-17-2).

- Okinawa Encyclopedia (3 volumes in Japanese), Okinawa Times, 1983.

Further reading[edit]

- John McLeod (1818), "(Lewchew)", Voyage of His Majesty's ship Alceste, along the coast of Corea to the island of Lewchew (2nd ed.), London: J. Murray

External links[edit]

- A collection of essays miscellaneous historical topics

- (in Japanese)沖縄の歴史情報(ORJ) Many Ryukyu historical texts.

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Many documents, including original and singular translations, concerning post-WWII Okinawa

- Wonder Okinawa, a comprehensive site run by the Okinawa Prefectural Government

- Information concerning UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Ryukyu Islands

- Early Ryukyuan History as described by the Chinese

- Ryukyuan coins information and pictures concerning minting and circulation

- Brief History of the Uchinanchu (Okinawans) Archived August 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine