Melting pot

A melting pot is a monocultural metaphor for a heterogeneous society becoming more homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative being a homogeneous society becoming more heterogeneous through the influx of foreign elements with different cultural backgrounds, possessing the potential to create disharmony within the previous culture. It can also create a harmonious hybridized society known as cultural amalgamation. In the United States, the term is often used to describe the cultural integration of immigrants to the country.[1] A related concept has been defined as "cultural additivity."[2]

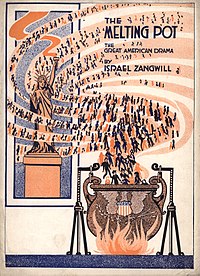

The melting-together metaphor was in use by the 1780s.[3][4] The exact term "melting pot" came into general usage in the United States after it was used as a metaphor describing a fusion of nationalities, cultures and ethnicities in Israel Zangwill's 1908 play of the same name.

The desirability of assimilation and the melting pot model has been rejected by proponents of multiculturalism,[5][6] who have suggested alternative metaphors to describe the current American society, such as a salad bowl, or kaleidoscope, in which different cultures mix, but remain distinct in some aspects.[7][8][9] The melting pot continues to be used as an assimilation model in vernacular and political discourse along with more inclusive models of assimilation in the academic debates on identity, adaptation and integration of immigrants into various political, social and economic spheres.[10]

Use of the term[edit]

The concept of immigrants "melting" into the receiving culture is found in the writings of J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur. In his Letters from an American Farmer (1782) Crèvecœur writes, in response to his own question, "What then is the American, this new man?" that the American is one who "leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the government he obeys, and the new rank he holds. He becomes an American by being received in the broad lap of our great Alma Mater. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labors and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world."[citation needed]

In 1845, Ralph Waldo Emerson, alluding to the development of European civilization out of the medieval Dark Ages, wrote in his private journal of America as the Utopian product of a culturally and racially mixed "smelting pot", but only in 1912 were his remarks first published.[citation needed]

A magazine article in 1876 used the metaphor explicitly:

The fusing process goes on as in a blast-furnace; one generation, a single year even—transforms the English, the German, the Irish emigrant into an American. Uniform institutions, ideas, language, the influence of the majority, bring us soon to a similar complexion; the individuality of the immigrant, almost even his traits of race and religion, fuse down in the democratic alembic like chips of brass thrown into the melting pot.[11]

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner also used the metaphor of immigrants melting into one American culture. In his essay The Significance of the Frontier in American History, he referred to the "composite nationality" of the American people, arguing that the frontier had functioned as a "crucible" where "the immigrants were Americanized, liberated and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics".[citation needed]

In his 1905 travel narrative The American Scene, Henry James discusses cultural intermixing in New York City as a "fusion, as of elements in solution in a vast hot pot".[12]

United States[edit]

Multiracial influences on culture[edit]

White Americans long regarded some elements of African-American culture quintessentially "American", while at the same time treating African Americans as second-class citizens. White appropriation, stereotyping and mimicking of black culture played an important role in the construction of an urban popular culture in which European immigrants could express themselves as Americans, through such traditions as blackface, minstrel shows and later in jazz and in early Hollywood cinema, notably in The Jazz Singer (1927).[13]

Analyzing the "racial masquerade" that was involved in creation of a white "melting pot" culture through the stereotyping and imitation of black and other non-white cultures in the early 20th century, historian Michael Rogin has commented: "Repudiating 1920s nativism, these films [Rogin discusses The Jazz Singer, Old San Francisco (1927), Whoopee! (1930), King of Jazz (1930) celebrate the melting pot. Unlike other racially stigmatized groups, white immigrants can put on and take off their mask of difference. But the freedom promised immigrants to make themselves over points to the vacancy, the violence, the deception, and the melancholy at the core of American self-fashioning".[13]

Ethnicity in films[edit]

This trend towards greater acceptance of ethnic and racial minorities was evident in popular culture in the combat films of World War II, starting with Bataan (1943). This film celebrated solidarity and cooperation between Americans of all races and ethnicities through the depiction of a multiracial American unit. At the time blacks and Japanese in the armed forces were still segregated, while Chinese and Indians were in integrated units.

Historian Richard Slotkin sees Bataan and the combat genre that sprang from it as the source of the "melting pot platoon", a cinematic and cultural convention symbolizing in the 1940s "an American community that did not yet exist", and thus presenting an implicit protest against racial segregation. However, Slotkin points out that ethnic and racial harmony within this platoon is predicated upon racist hatred for the Japanese enemy: "the emotion which enables the platoon to transcend racial prejudice is itself a virulent expression of racial hatred...The final heat which blends the ingredients of the melting pot is rage against an enemy which is fully dehumanized as a race of 'dirty monkeys.'" He sees this racist rage as an expression of "the unresolved tension between racialism and civic egalitarianism in American life".[14]

Olympic Games[edit]

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City strongly revived the melting pot image, returning to a bedrock form of American nationalism and patriotism. The reemergence of Olympic melting pot discourse was driven especially by the unprecedented success of African Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans in events traditionally associated with Europeans and white North Americans such as speed skating and the bobsled.[15] The 2002 Winter Olympics was also a showcase of American religious freedom and cultural tolerance of the history of Utah's large majority population of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well representation of Muslim Americans and other religious groups in the U.S. Olympic team.[16][17]

Melting pot and cultural pluralism[edit]

In Henry Ford's Ford English School (established in 1914), the graduation ceremony for immigrant employees involved symbolically stepping off an immigrant ship and passing through the melting pot, entering at one end in costumes designating their nationality and emerging at the other end in identical suits and waving American flags.[18][19]

In response to the pressure exerted on immigrants to culturally assimilate and also as a reaction against the denigration of the culture of non-Anglo white immigrants by Nativists, intellectuals on the left, such as Horace Kallen in Democracy Versus the Melting-Pot (1915), and Randolph Bourne in Trans-National America (1916), laid the foundations for the concept of cultural pluralism. This term was coined by Kallen.[20]

In the United States, where the term melting pot is still commonly used, the ideas of cultural pluralism and multiculturalism have, in some circles, taken precedence over the idea of assimilation.[21][22][23] Alternate models where immigrants retain their native cultures such as the "salad bowl"[24] or the "symphony"[21] are more often used by sociologists to describe how cultures and ethnicities mix in the United States. Mayor David Dinkins, when referring to New York City, described it as "not a melting pot, but a gorgeous mosaic...of race and religious faith, of national origin and sexual orientation – of individuals whose families arrived yesterday and generations ago..."[25]

Since the 1960s, much research in Sociology and History has disregarded the melting pot theory for describing interethnic relations in the United States and other countries.[21][22][23]

Whether to support a melting-pot or multicultural approach has developed into an issue of much debate within some countries. For example, the French and British governments and populace are currently debating whether Islamic cultural practices and dress conflict with their attempts to form culturally unified countries.[26]

Use in other regions[edit]

Israel[edit]

Today the reaction to this doctrine is ambivalent; some say that it was a necessary measure in the founding years, while others claim that it amounted to cultural oppression.[27] Others argue that the melting pot policy did not achieve its declared target: for example, the persons born in Israel are more similar from an economic point of view to their parents than to the rest of the population.[28]

Southeast Asia[edit]

The term has been used to describe a number of countries in Southeast Asia. Given the region's location and importance to trade routes between China and the Western world, certain countries in the region have become ethnically diverse.[29] In Vietnam, a relevant phenomenon is "tam giáo đồng nguyên", meaning the co-existence and co-influence of three major religious teaching schools (Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism), which shows a process defined as "cultural addivity".[30]

In popular culture[edit]

- Animated educational series Schoolhouse Rock! has a song entitled "The Great American Melting Pot".[31]

Quotations[edit]

Man is the most composite of all creatures.... Well, as in the old burning of the Temple at Corinth, by the melting and intermixture of silver and gold and other metals a new compound more precious than any, called Corinthian brass, was formed; so in this continent—asylum of all nations—the energy of Irish, Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Cossacks, and all the European tribes—of the Africans, and of the Polynesians—will construct a new race, a new religion, a new state, a new literature, which will be as vigorous as the new Europe which came out of the smelting-pot of the Dark Ages, or that which earlier emerged from the Pelasgic and Etruscan barbarism.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, journal entry, 1845, first published 1912 in Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson with Annotations, Vol. IIV, 116

These good people are future 'Yankees.' By next year they will be wearing the clothes of their new country, and by the following year they will be speaking its language. Their children will grow up and will no longer even remember the mother country. America is the melting pot in which all the nations of the world come to be fused into a single mass and cast in a uniform mold.

— Ernest Duvergier de Hauranne, English translation entitled "A Frenchman in Lincoln’s America" [Volume 1] (Lakewood Classics, 1974), 240-41, of "Huit Mois en Amérique: Lettres et Notes de Voyage, 1864-1865" (1866).

No reverberatory effect of The Great War has caused American public opinion more solicitude than the failure of the 'melting-pot.' The discovery of diverse nationalistic feelings among our great alien population has come to most people as an intense shock.

— Randolph Bourne, "Trans-National America", in Atlantic Monthly, 118 (July 1916), 86–97

Blacks, Chinese, Puerto Ricans, etcetera, could not melt into the pot. They could be used as wood to produce the fire for the pot, but they could not be used as material to be melted into the pot.[32]

— Eduardo-Bonilla Silva, Race: The Power of an Illusion

See also[edit]

- Cultural amalgamation

- Cultural assimilation

- Cultural diversity

- Cultural pluralism

- Ethnic group

- Hyphenated American

- Interculturalism

- Lusotropicalism

- More Irish than the Irish themselves

- Multiculturalism in Canada

- Multicultural media in Canada

- Nation-building

- Race of the future

- Racial integration

- Social integration

- Transculturation

- Zhonghua minzu

References[edit]

- ^ United States Bureau of the Census (1995). Celebrating our nation's diversity: a teaching supplement for grades K–12. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census. pp. 1–. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2018). "Cultural additivity: behavioural insights from the interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in folktales". Palgrave Communications. 4 (1): 143. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0189-2. S2CID 54444540.

- ^ p. 50 See "..whether assimilation ought to be seen as an egalitarian or hegemonic process, ...two viewpoints are represented by the melting-pot and Anglo-conformity models, respectively" Jason J. McDonald (2007). American Ethnic History: Themes and Perspectives. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-0748616343. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Larry A. Samovar; Richard E. Porter; Edwin R. McDaniel (2011). Intercultural Communication: A Reader. Cengage Learning. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-0495898313. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Joachim Von Meien (2007). The Multiculturalism vs. Integration Debate in Great Britain. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3638766470. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Eva Kolb (2009). The Evolution of New York City's Multiculturalism: Melting Pot or Salad Bowl: Immigrants in New York from the 19th Century Until the End of the Gilded Age. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3837093032. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Lawrence H. Fuchs (1990). The American Kaleidoscope: Race, Ethnicity, and the Civic Culture. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-0819562500. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Tamar Jacoby (2004). Reinventing The Melting Pot: The New Immigrants And What It Means To Be American. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465036356. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Jason J. McDonald (2007). American Ethnic History: Themes and Perspectives. ISBN 978-0813542270

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 457. ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ Titus Munson Coan, "A New Country", The Galaxy Volume 0019, Issue 4 (April 1875), p. 463 online

- ^ James, Henry (1968). The American Scene. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0861550188., p. 116

- ^ a b Rogin, Michael (December 1992). "Making America Home: Racial Masquerade and Ethnic Assimilation in the Transition to Talking Pictures" (PDF). The Journal of American History. 79 (3). Organization of American Historians: 1050–77. doi:10.2307/2080798. JSTOR 2080798. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ Slotkin, Richard (Fall 2001). "Unit Pride: Ethnic Platoons and the Myths of American Nationality". American Literary History. 13 (9). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 469–98. doi:10.1093/alh/13.3.469. S2CID 143996198. Archived from the original on 2011-11-30. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Mark Dyerson, "'America's Athletic Missionaries': Political Performance, Olympic Spectacle and the Quest for an American National Culture, 1896–1912," International Journal of the History of Sport 2008 25(2): 185–203; Dyerson, "Return to the Melting Pot: An Old American Olympic Story," International Journal of the History of Sport 2008 25(2): 204–23

- ^ Ethan R. Yorgason (2093). Transformation of the Mormon culture region. pp. 1, 190 [ISBN missing]

- ^ W. Paul Reeve and Ardis E. Parshall, eds. (2010). Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 318 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Ford English School". Automobile in American Life and Society. Dearborn: University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Immigration". University of Nancy. Archived from the original on 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Noam Pianko, "'The True Liberalism of Zionism': Horace Kallen, Jewish Nationalism, and the Limits of American Pluralism," American Jewish History, December 2008, Vol. 94, Issue 4, pp. 299–329,

- ^ a b c Milton, Gordon (1964). Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195008960.

- ^ a b Adams, J.Q.; Strother-Adams, Pearlie (2001). Dealing with Diversity. Chicago: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co. ISBN 078728145X.

- ^ a b Glazer, Nathan; Moynihan, Daniel P. (1970). Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians and Irish of New York City (2nd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 026257022X.

- ^ Millet, Joyce. "Understanding American Culture: From Melting Pot to Salad Bowl". Cultural Savvy. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "David Dinkins: "A Mayor's Life: Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic"". Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. 1945-04-12. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Cowell, Alan (2006-10-15). "Islamic schools at heart of British debate on integration". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Liphshiz, Cnaan (May 9, 2008). "Melting pot' approach in the army was a mistake, says IDF absorption head". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Yitzhaki, Shlomo and Schechtman, Edna The "Melting Pot": A Success Story? Journal of Economic Inequality, Vol; 7, No. 2, June 2009, pp. 137–51. Earlier version by Schechtman, Edna and Yitzhaki, Shlomo Archived 2013-11-09 at the Wayback Machine, Working Paper No. 32, Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, Nov. 2007, i + 30 pp.

- ^ Kumar, Sree; Siddique, Sharon (2008). Southeast Asia: The Diversity Dilemma. Select Publishing. ISBN 978-9814022385.

- ^ Napier, Nancy K.; Pham, Hiep-Hung; Nguyen, Ha; Nguyen, Hong Kong; Ho, Manh-Toan; Vuong, Thu-Trang; Cuong, Nghiem Phu Kien; Bui, Quang-Khiem; Nhue, Dam; La, Viet-Phuong; Ho, Tung; Vuong, Quan Hoang (March 4, 2018). "'Cultural additivity' and how the values and norms of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism co-exist, interact, and influence Vietnamese society: A Bayesian analysis of long-standing folktales, using R and Stan". CEB WP No.18/015 (Centre Emile Bernheim, Université Libre de Bruxelles). arXiv:1803.06304. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3134541. S2CID 88505467. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ "The Great American Melting Pot". School House Rock. Archived from the original on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Episode 3: The House We Live In (transcript)", Race: The Power of an Illusion, archived from the original on 16 September 2009, retrieved 5 Feb 2009

External links[edit]

- Booth, William (February 22, 1998). "One Nation, Indivisible: Is It History?". Myth of the Melting Pot: America's Racial and Ethnic Divide (story series). The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "Homepage". The Melting Pot NYC. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2017.