Metcalfe's law

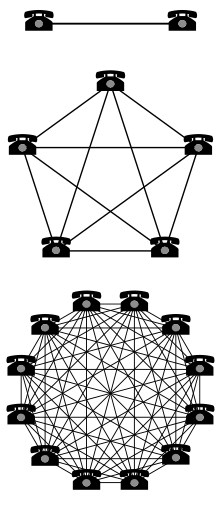

Metcalfe's law states that the financial value or influence of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system (n2). The law is named after Robert Metcalfe and was first proposed in 1980, albeit not in terms of users, but rather of "compatible communicating devices" (e.g., fax machines, telephones).[1] It later became associated with users on the Ethernet after a September 1993 Forbes article by George Gilder.[2]

Network effects[edit]

Metcalfe's law characterizes many of the network effects of communication technologies and networks such as the Internet, social networking and the World Wide Web. Former Chairman of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission Reed Hundt said that this law gives the most understanding to the workings of the present-day Internet.[3] Mathematically, Metcalfe's Law shows that the number of unique possible connections in an -node connection can be expressed as the triangular number , which is asymptotically proportional to .

The law has often been illustrated using the example of fax machines: a single fax machine on its own is useless, but the value of every fax machine increases with the total number of fax machines in the network, because the total number of people with whom each user may send and receive documents increases.[4] This is common illustration to explain Network effect. Thus, in any social networks, the greater the number of users with the service, the more valuable the service becomes to the community.

History and derivation[edit]

Metcalfe's law was conceived in 1983 in a presentation to the 3Com sales force.[5] It stated V would be proportional to the total number of possible connections, or approximately n-squared.

The original incarnation was careful to delineate between a linear cost (Cn), non-linear growth(n2) and a non-constant proportionality factor affinity (A). The break-even point point where costs are recouped is given by:

There may be diseconomies of network scale that eventually drive values down with increasing size. So, if V=A*n2, it could be that A (for “affinity,” value per connection) is also a function of n and heads down after some network size, overwhelming n2.

Growth of n[edit]

Network size, and hence value, does not grow unbounded but is constrained by practical limitations such as infrastructure, access to technology, and bounded rationality such as Dunbar's number. It is almost always the case that user growth n reaches a saturation point. With technologies, substitutes, competitors and technical obsolescence constrain growth of n. Growth of n is typically assumed to follow a sigmoid function such as a logistic curve or Gompertz curve.

Density[edit]

A is also governed by the connectivity or density of the network topology. In an undirected network, every edge connects two nodes such that there are 2m nodes per edge. The proportion of nodes in actual contact are given by .

The maximum possible number of edges in a simple network (i.e. one with no multi-edges or self-edges) is . Therefore the density ρ of a network is the faction of those edges that are actually present is:

which for large networks is approximated by .[7]

Limitations[edit]

Metcalfe's law assumes that the value of each node is of equal benefit.[3] If this is not the case, for example because one fax machine serves 60 workers in a company, the second fax machine serves half of that, the third one third, and so on, then the relative value of an additional connection decreases. Likewise, in social networks, if users that join later use the network less than early adopters, then the benefit of each additional user may lessen, making the overall network less efficient if costs per users are fixed.

Modified models[edit]

Within the context of social networks, many, including Metcalfe himself, have proposed modified models in which the value of the network grows as rather than .[8][3] Reed[non sequitur] and Andrew Odlyzko have sought out possible relationships to Metcalfe's Law in terms of describing the relationship of a network and one can read about how those are related. Tongia and Wilson also examine the related question of the costs to those excluded.[9]

Validation in data[edit]

For more than 30 years, there was little concrete evidence in support of the law. Finally, in July 2013, Dutch researchers analyzed European Internet-usage patterns over a long-enough time[specify] and found proportionality for small values of and proportionality for large values of .[10] A few months later, Metcalfe himself provided further proof by using Facebook's data over the past 10 years to show a good fit for Metcalfe's law.[11]

In 2015, Zhang, Liu, and Xu parameterized the Metcalfe function in data from Tencent and Facebook. Their work showed that Metcalfe's law held for both, despite differences in audience between the two sites (Facebook serving a worldwide audience and Tencent serving only Chinese users). The functions for the two sites were and respectively.[12] One of the earliest mentions of the Metcalfe Law in the contest of Bitcoin was by a Reddit post by Santostasi in 2014. He compared the observed generalized Metcalfe behavior for Bitcoin to the Zipf's Law and the theoretical Metcalfe result [13]. The Metcalfe's Law is a critical component of Santostasi's Bitcoin Power Law Theory. [14]. In a working paper, Peterson linked time-value-of-money concepts to Metcalfe value using Bitcoin and Facebook as numerical examples of the proof,[15] and in 2018 applied Metcalfe's law to Bitcoin, showing that over 70% of variance in Bitcoin value was explained by applying Metcalfe's law to increases in Bitcoin network size.[16]

In a 2024 interview, mathematician Terrence Tao emphasized the importance of universality and networking within the mathematics community, for which he cited the Metcalfe's Law. Tao believes that a larger audience leads to more connections, which ultimately results in positive developments within the community. For this, he cited Metcalfe's law to support this perspective. Tao further stated, "my whole career experience has been sort of the more connections equals just better stuff happening".[17]

See also[edit]

- Anti-rival good

- Beckstrom's law

- List of eponymous laws

- Matching (graph theory)

- Matthew effect

- Pareto principle

- Reed's law

- Sarnoff's law

References[edit]

- ^ Simeonov, Simeon (26 July 2006). "Metcalfe's Law: more misunderstood than wrong?". HighContrast: Innovation & venture capital in the post-broadband era.

- ^ Shapiro, Carl; Varian, Hal R. (1999). Information Rules. Harvard Business Press. ISBN 9780875848631.

- ^ a b c Briscoe, Bob; Odlyzko, Andrew; Tilly, Benjamin (July 2006). "Metcalfe's Law is Wrong". IEEE Spectrum. 43 (7): 34–39. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2006.1653003. S2CID 45462851. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Tongia, Rahul; Wilson, E. J. (8 April 2011). "Network Theory| The Flip Side of Metcalfe's Law: Multiple and Growing Costs of Network Exclusion". International Journal of Communication.

- ^ Metcalfe, Bob (December 2013). "Metcalfe's Law after 40 Years of Ethernet". Computer. 46 (12): 26–31. doi:10.1109/MC.2013.374. ISSN 1558-0814. S2CID 206448593.

- ^ Metcalfe, Robert (18 August 2006). "Guest Blogger Bob Metcalfe: Metcalfe's Law Recurses down the Long Tail of Social Networks". VC Mike's Blog.

- ^ Newman, Mark E. J. (2019). "Mathematics of Networks" in Networks. Oxford University Press. pp. 126–128. ISBN 9780198805090.

- ^ "Guest Blogger Bob Metcalfe: Metcalfe's Law Recurses Down the Long Tail of Social Networks". 18 August 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Tongia, Rahul; Wilson, Ernest (September 2007). "The Flip Side of Metcalfe's Law: Multiple and Growing Costs of Network Exclusion". International Journal of Communication. 5: 17. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ Madureira, António; den Hartog, Frank; Bouwman, Harry; Baken, Nico (2013). "Empirical validation of Metcalfe's law: How Internet usage patterns have changed over time". Information Economics and Policy. 25 (4): 246–256. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2013.07.002.

- ^ Metcalfe, Bob (2013). "Metcalfe's law after 40 years of Ethernet". IEEE Computer. 46 (12): 26–31. doi:10.1109/MC.2013.374. S2CID 206448593.

- ^ Zhang, Xing-Zhou; Liu, Jing-Jie; Xu, Zhi-Wei (2015). "Tencent and Facebook Data Validate Metcalfe's Law". Journal of Computer Science and Technology. 30 (2): 246–251. doi:10.1007/s11390-015-1518-1. S2CID 255158958.

- ^ "Bitcoin compared with Metcalfe's and Zipf's law". 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ "The Bitcoin Power Law Theory". 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Peterson, Timothy (2019). "Bitcoin Spreads Like a Virus". Working Paper. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3356098. S2CID 159240517.

- ^ Peterson, Timothy (2018). "Metcalfe's Law as a Model for Bitcoin's Value". Alternative Investment Analyst Review. 7 (2): 9–18. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3078248. S2CID 158572041.

- ^ Strogatz, Steven (1 February 2024). "What Makes for 'Good' Mathematics?". Quanta Magazine.

Further reading[edit]

- Smith, David; Skelley, C. A. (Summer 2006). "Globalization Transformation" (PDF). Tennessee Business Magazine. pp. 17–19.

External links[edit]

- A Group Is Its Own Worst Enemy. Clay Shirky's keynote speech on Social Software at the O'Reilly Emerging Technology conference, Santa Clara, April 24, 2003. The fourth of his "Four Things to Design For" is: "And, finally, you have to find a way to spare the group from scale. Scale alone kills conversations, because conversations require dense two-way conversations. In conversational contexts, Metcalfe's law is a drag."