Prussian education system

The Prussian education system refers to the system of education established in Prussia as a result of educational reforms in the late 18th and early 19th century, which has had widespread influence since. The Prussian education system was introduced as a basic concept in the late 18th century and was significantly enhanced after Prussia's defeat in the early stages of the Napoleonic Wars. The Prussian educational reforms inspired similar changes in other countries, and remain an important consideration in accounting for modern nation-building projects and their consequences.[1]

The term itself is not used in German literature, which refers to the primary aspects of the Humboldtian education ideal respectively as the Prussian reforms; however, the basic concept has led to various debates and controversies. Twenty-first century primary and secondary education in Germany and beyond still embodies the legacy of the Prussian education system.

Origin[edit]

The basic foundations of a generic Prussian primary education system were laid out by Frederick the Great with his Generallandschulreglement, a decree of 1763 which was written by Johann Julius Hecker. Hecker had already before (in 1748) founded the first teacher's seminary in Prussia. His concept of providing teachers with the means to cultivate mulberries for homespun silk, which was one of Frederick's favorite projects, found the King's favour.[2] It expanded the existing schooling system significantly and required that all young citizens, both girls and boys, be educated by mainly municipality-funded schools from the age of 5 to 13 or 14. Prussia was among the first countries in the world to introduce tax-funded and generally compulsory primary education.[3] In comparison, in France and Great Britain, compulsory schooling was not successfully enacted until the 1880s.[4]

The Prussian system consisted of an eight-year course of primary education, called Volksschule. It provided not only basic technical skills needed in a modernizing world (such as reading and writing), but also music (singing) and religious (Christian) education in close cooperation with the churches and tried to impose a strict ethos of duty, sobriety and discipline. Mathematics and calculus were not compulsory at the start, and taking such courses required additional payment by parents. Frederick the Great also formalized further educational stages, the Realschule and as the highest stage the gymnasium (state-funded secondary school), which served as a university-preparatory school.[5]

Construction of schools received some state support, but they were often built on private initiative. Friedrich Eberhard von Rochow, a member of the local gentry and former cavalry officer in Reckahn, Brandenburg, installed such a school. Von Rochow cooperated with Heinrich Julius Bruns (1746–1794), a talented teacher of modest background. The two installed a model school for rural education that attracted more than 1,200 notable visitors between 1777 and 1794.[6]

The Prussian system, after its modest beginnings, succeeded in reaching compulsory attendance, specific training for teachers, national testing for all students (both female and male students), a prescribed national curriculum for each grade and mandatory kindergarten.[7] Training of teachers was increasingly organized via private seminaries. Hecker had already in 1748 founded the first "Lehrerseminar", but the density and impact of the seminary system improving significantly until the end of the 18th century.[8] In 1810, Prussia introduced state certification requirements for teachers, which significantly raised the standard of teaching.[9] The final examination, Abitur, was introduced in 1788, implemented in all Prussian secondary schools by 1812 and extended to all of Germany in 1871. Passing the Abitur was a prerequisite to entering the learned professions and higher echelons of the civil service. The state-controlled Abitur remains in place in modern Germany.

The Prussian system had by the 1830s attained the following characteristics:[10]

- Free primary schooling, at least for poor citizens

- Professional teachers trained in specialized colleges

- A basic salary for teachers and recognition of teaching as a profession

- An extended school year to better involve children of farmers

- Funding to build schools

- Supervision at national and classroom level to ensure quality instruction

- Curriculum inculcating a strong national identity, involvement of science and technology

- Secular instruction (but with religion as a topic included in the curriculum)

The German states in the 19th century were world leaders in prestigious education and Prussia set the pace.[11][12] For boys free public education was widely available, and the gymnasium system for elite students was highly professionalized. The modern university system emerged from the 19th century German universities, especially Friedrich Wilhelm University (now named Humboldt University of Berlin). It pioneered the model of the research university with well-defined career tracks for professors.[13] The United States, for example, paid close attention to German models. Families focused on educating their sons. The traditional schooling for girls was generally provided by mothers and governesses. Elite families increasingly favoured Catholic convent boarding schools for their daughters. Prussia's Kulturkampf laws in the 1870s limited Catholic schools thus providing an opening for a large number of new private schools for girls.[14]

Outreach[edit]

The overall system was soon widely admired for its efficiency and reduction of illiteracy, and inspired education leaders in other German states and a number of other countries, including Japan and the United States.[15]

The underlying Humboldtian educational ideal of brothers Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt was about much more than primary education; it strived for academic freedom and the education of both cosmopolitan-minded and loyal citizens from the earliest levels. The Prussian system had strong backing in the traditional German admiration and respect for Bildung as an individual's drive to cultivate oneself from within.[16]

Drivers and hindrances[edit]

Major drivers for improved education in Prussia since the 18th century had a background in the middle and upper middle strata of society and were pioneered by the Bildungsbürgertum. The concept as such faced strong resistance both from the top, as major players in the ruling nobility feared increasing literacy among peasants and workers would raise unrest, and from the very poor, who preferred to use their children as early as possible for rural or industrial labor.[2]

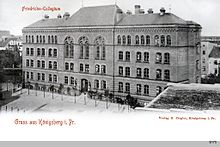

The system's proponents overcame such resistance with the help of foreign pressure and internal failures, after the defeat of Prussia in the early stages of the Napoleonic Wars. After the military blunder of Prussian drill and line formation against the levée en masse of the French revolutionary army in the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt in 1806, reformers and German nationalists urged for major improvements in education. In 1809 Wilhelm von Humboldt, having been appointed minister of education, promoted his idea of a generic education based on a neohumanist ideal of broad general knowledge, in full academic freedom without any determination or restriction by status, profession or wealth. Humboldt's Königsberger Schulplan [de] was one of the earliest white papers to lay out a reform of a country's educational system as a whole.[17] Humboldt's concept still forms the foundation of the contemporary German education system.[18] The Prussian system provided compulsory and basic schooling for everyone, but the significantly higher fees for attending gymnasium or a university imposed a high barrier between upper social strata and middle and lower social strata.[19]

Interaction with the German national movement[edit]

In 1807 Johann Gottlieb Fichte had urged a new form of education in his Addresses to the German Nation. While Prussian (military) drill in the times before had been about obedience to orders without any leeway, Fichte asked for shaping of the personality of students: "The citizens should be made able and willing to use their own minds to achieve higher goals in the framework of a future unified German nation state."[20] Fichte and other philosophers, such as the Brothers Grimm, tried to circumvent the nobility's resistance to a common German nation state via proposing the concept of a Kulturnation, nationhood without needing a state but based on a common language, musical compositions and songs, shared fairy tales and legends and a common ethos and educational canon.[21]

Various German national movement leaders engaged themselves in educational reform. For example, Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778–1852), dubbed the Turnvater, was the father of German gymnastics and a student fraternity leader and nationalist but failed in his nationalist efforts; between 1820 and 1842 Jahn's gymnastics movement was forbidden because of his proto-Nazi politics.[22] Later on, Jahn and others were successful in integrating physical education and sports into Prussian and overall German curricula and popular culture.[23]

By 1870, the Prussian system began to privilege High German as an official language against various ethnic groups (such as Poles, Sorbs and Danes) living in Prussia and other German states. Previous attempts to establish "Utraquism" schools (bilingual education) in the east of Prussia had been identified with high illiteracy rates there.[24]

Interaction with religion[edit]

Pietism, a reformist group within Lutheranism, forged a political alliance with the King of Prussia based on a mutual interest in breaking the dominance of the Lutheran state church. The Prussian Kings, Calvinists among Lutherans, feared the influence of the Lutheran state church and its close connections with the provincial nobility, while Pietists suffered from persecution by the Lutheran orthodoxy.

Bolstered by royal patronage, Pietism replaced the Lutheran church as the effective state religion by the 1760s. Pietist theology stressed the need for "inner spirituality" (Innerlichkeit [de]), to be found through the reading of Scripture. Consequently, Pietists helped form the principles of the modern public school system, including the stress on literacy, while more Calvinism-based educational reformers (English and Swiss) asked for externally oriented, utilitarian approaches and were critical of internally soul searching idealism.[25]

Prussia was able to leverage the Protestant Church as a partner and ally in the setup of its educational system. Prussian ministers, particularly Karl Abraham Freiherr von Zedlitz, sought to introduce a more centralized, uniform system administered by the state during the 18th century. The implementation of the Prussian General Land Law of 1794 was a major step toward this goal. However, there remains in Germany to the present a complicated system of burden sharing between municipalities and state administration for primary and secondary education. The various confessions still have a strong say, contribute religious instruction as a regular topic in schools and receive state funding to allow them to provide preschool education and kindergarten.

In comparison, the French and Austrian education systems faced major setbacks due to ongoing conflicts with the Catholic Church and its educational role.[4] The introduction of compulsory schooling in France was delayed till the 1880s.

Political and cultural role of teachers[edit]

Generations of Prussian and also German teachers, who in the 18th century often had no formal education and in the very beginning often were untrained former petty officers, tried to gain more academic recognition, training and better pay and played an important role in various protest and reform movements throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. Namely, the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states and the protests of 1968 saw a strong involvement of (future) teachers.[2] There is a long tradition of parody and ridicule, where teachers were being depicted in a janus-faced manner as either authoritarian drill masters or, on the other hand, poor wretches which were suffering the constant spite of pranking pupils, negligent parents and spiteful local authorities.[26]

A 2010 book title like "Germany, your teachers; why the future of our children is being decided in the classroom" shows the 18th and 19th century Enlightenment ideals of teachers[26] educating the nation about its most sacred and important issues.[27] The notion of Biedermeier, a petty bourgeois image of the age between 1830 and 1848, was coined on Samuel Friedrich Sauter, a school master and poet which had written the famous German song "Das arme Dorfschulmeisterlein" (The poor little schoolmaster).[26] Actually the 18th primary teachers income was a third of a parish priest[26] and teachers were being described as being as uppity as proverbially poor. However German notion of homeschooling was less than favorable, Germans deemed the school system as being necessary. E.g. Heinrich Spoerls 1933 "escapist masterpiece"[28] novel (and movie) Die Feuerzangenbowle tells the (till the present) popular story of a writer going undercover as a student at a small town school after his friends in Berlin tell him that he missed out on the best part of growing up by being homeschooled.

Spread to other countries[edit]

State-oriented mass educational systems were instituted in the 19th century in the rest of Europe. They have become an indispensable component of modern nation-states.[citation needed] Public education was widely institutionalized throughout the world and its development has a close link with nation-building, which often occurred in parallel. Such systems were put in place when the idea of mass education was not yet taken for granted.[29]

Examples[edit]

In Austria, Empress Maria Theresa had already made use of Prussian pedagogical methods in 1774 as a means to strengthen her hold over Austria.[30] The introduction of compulsory primary schooling in Austria based on the Prussian model had a powerful role, in establishing this and others modern nation states shape and formation.[30]

The Prussian reforms in education spread quickly through Europe, particularly after the French Revolution. The Napoleonic Wars first allowed the system to be enhanced after the 1806 crushing defeat of Prussia itself and then to spread in parallel with the rise and territorial gains of Prussia after the Vienna Congress. Heinrich Spoerl's son Alexander Spoerl's Memoiren eines mittelmäßigen Schülers (Memories of a Mediocre Student) describes and satirises the role of the formational systems in the Prussian Rhine Province during the early 20th century, in a famous novel of 1950, dedicated to Libertas Schulze-Boysen.

While the Russian Empire was among the most reactionary regimes with regard to common education, the German ruling class in Estonia and Latvia managed to introduce the system there under Russian rule.[31][32] The Prussian principles were adopted by the governments in Norway and Sweden to create the basis of the primary (grundskola) and secondary (gymnasium) schools across Scandinavia. Unlike in Prussia, the Swedish system aimed to expand even secondary schooling to the peasants and workers. As well in Finland, then a Russian grand duchy with a strong Swedish elite, the system was adopted. Education and the propagation of the national epic, the Kalevala, was crucial for the Finnish nationalist Fennoman movement. The Finnish language achieved equal legal status with Swedish in 1892.

France and the UK failed until the 1880s to introduce compulsory education, France due to conflicts between a radical secular state and the Catholic Church. In Scotland, local church-controlled schools were replaced by a state system in 1872. In England and Wales, the government started to subsidise schooling in 1833, various measures followed till a local School Boards were set up under the Forster Act of 1870, local School Boards providing free (taxpayer financed) and compulsory schooling were made universal in England and Wales by the Act of 1891, schooling having been made compulsory by the Act of 1880. However, both private schools and education by means other than schooling remained legal in the United Kingdom.

United States[edit]

Early 19th-century American educators were also fascinated by German educational trends. In 1818, John Griscom gave a favorable report of Prussian education. English translations were made of French philosopher Victor Cousin's work, Report on the State of Public Education in Prussia. Calvin E. Stowe, Henry Barnard, Horace Mann, George Bancroft and Joseph Cogswell all had a vigorous interest in German education. The Prussian approach was used for example in the Michigan Constitution of 1835, which fully embraced the Prussian system by introducing a range of primary schools, secondary schools, and the University of Michigan itself, all administered by the state and supported with tax-based funding. However, the concepts in the Prussian reforms of primordial education, Bildung and its close interaction of education, society and nation-building are in conflict with some aspects of American state-skeptical libertarian thinking.[33]

In 1843, Mann traveled to Germany to investigate how the educational process worked. Upon his return to the United States, he incorporated his experiences in his advocacy for the common school movement in Massachusetts. Mann persuaded his fellow modernizers, especially those in his Whig Party, to legislate tax-supported elementary public education in their states. New York state soon set up the same method in 12 different schools on a trial basis. Most northern states adopted one version or another of the system he established in Massachusetts, especially the program for "normal schools" to train professional teachers..[34]

Policy borrowing and exchange[edit]

The basic concept of a state-oriented and administered mass educational system is still not granted in the English-speaking world, where either the role of the state as such or the role of state control specifically in education faces still (respectively again) considerable skepticism.[29] The actual process of "policy borrowing" between different educational systems has been rather complex and differentiated.[35] Mann himself had stressed in 1844 that the US should copy the positive aspects of the Prussian system but not adopt Prussia's obedience to the authorities.[36] One of the important differences is that in the German tradition, there is stronger reference to the state as an important principle, as introduced for example by Hegel's philosophy of the state, which is in opposition to the Anglo-American contract-based idea of the state.[37]

Drill and serfdom[edit]

Early Prussian reformers took major steps to abandon both serfdom and the line formation as early as 1807 and introduced mission-type tactics in the Prussian military in the same year. The latter enlarged freedom in execution of overall military strategies and had a major influence in the German and Prussian industrial culture, which profited from the Prussian reformers' introduction of greater economic freedom. The mission-type concept, which was kept by later German armed forces, required a high level of understanding, literacy (and intense training and education) at all levels and actively invited involvement and independent decision making by the lower ranks. Its intense interaction with the Prussian education system has led to the proverbial statement, "The battles of Königgrätz (1866) and Sedan (1870) have been decided by the Prussian primary teacher".[38]

Legacy of the Prussian system after the end of the monarchy[edit]

In 1918, the Kingdom of Prussia became a republic. Socialist Konrad Haenisch, the first education minister (Kultusminister), denounced what he called the "demons of morbid subservience, mistrust, and lies" in secondary schools.[39] However, Haenisch's and other radical left approaches were rather short-lived. They failed to introduce an Einheitsschule, a one-size-fits-all unified secular comprehensive school, throughout Germany.[40]

The Weimarer Schulkompromiss [de] (Weimar educational compromise) of 1919 confirmed the tripartite Prussian system, ongoing church influence on education, and religion as a regular topic, and it allowed for peculiarities and individual influence of the German states, widely frustrating the ambitions of radical leftist educational reformers.[40] Still, Prussian educational expert Erich Hylla [de] (1887–1976) provided various studies (with titles such as "School of Democracy") of the US education system for the Prussian government in the 1920s.[36]

The Nazi government's 1933 Gleichschaltung did away with state's rights, church influence and democracy and tried to impose a unified totalitarian education system and a Nazi version of the Einheitsschule, with strong premilitary and antisemitic aspects.

Legacy of the Prussian System after 1945[edit]

After 1945, the Weimar educational compromise again set the tone for the reconstruction of the state-specific educational system as laid out in the Prussian model. In 1946 the US occupation forces failed completely in their attempt to install comprehensive and secular schooling in the US Occupation Zone. This approach had been endorsed by High Commissioner John J. McCloy and was led by the high-ranking progressive education reformer Richard Thomas Alexander,[41] but it faced determined German resistance.[41]

The fiercest defender of the originally Prussian tripartite concept and humanist educational tradition was archconservative Alois Hundhammer, a former Bavarian monarchist, devout Catholic enemy of the Nazis and (with regard to the individual statehood of Bavaria) firebrand anti-Prussian coauthor of the 1946 Constitution of Bavaria. Hundhammer, as soon as he was appointed Bavarian minister of Culture and Education, was quick to use the newly granted freedoms, attacking Alexander in radio speeches and raising rumors about Alexander's secularism, which led to parents' and teachers' associations expressing fears about a reduction in the quality of education.[42] Hundhammer involved Michael von Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich, to contact New York Cardinal Francis J. Spellman, who intervened with the US forces; the reform attempts were abolished as soon as 1948.[42]

Current debates referring to the Prussian legacy[edit]

The Prussian legacy of a mainly tripartite system of education with less comprehensive schooling and selection of children as early as the fourth grade has led to controversies that persist to the present.[43] It has been deemed to reflect 19th-century thinking along class lines.[44] One of the basic tenets of the specific Prussian system is expressed in the fact that education in Germany is, against the aim of the 19th-century national movement, not directed by the federal government. The individual states maintain Kulturhoheit (cultural predominance) on educational matters.

The Humboldt approach, a central pillar of the Prussian system and of German education to the present day, is still influential and being used in various discussions. The present German universities charge no or moderate tuition fees. The perceived lack of universities on the cutting edge in both research and education has been recently countered via the German Universities Excellence Initiative, which is mainly driven and funded at the federal level.

Germany still focuses on a broad Allgemeinbildung (both 'generic knowledge' and 'knowledge for the common people') and provides an internationally recognized in-depth dual-track vocational education system, but leaves educational responsibility to individual states. The country faces ongoing controversies about the Prussian legacy of a stratified tripartite educational system versus Comprehensive schooling and with regard to the interpretation of the PISA studies.[45] Some German PISA critics opposed its utilitarian "value-for-money" competence approach, as being in conflict with teaching freedom, while German proponents of the PISA assessment referred to the practical usability of Humboldt's approach and the Prussian educational system derived from it.[25]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ European Universities from the Enlightenment to 1914 R. D. Anderson 2004 ISBN 978-0-19-820660-6 DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206606.001.0001

- ^ a b c Volkmar Wittmütz Die preussische Elementarschule im 19. Jahrhundert Clio-online

- ^ James van Horn Melton, Absolutism and the Eighteenth-Century Origins of Compulsory Schooling in Prussia and Austria (2003)

- ^ a b Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal and David Strang, "Construction of the First Mass Education Systems in Nineteenth-Century Europe" Sociology of Education, Vol. 62, No. 4 (Oct., 1989), pp. 277-288 Published by: American Sociological Association

- ^ Christopher Clark, Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947 (2008) ch 7

- ^ Frank Tosch (Ed.): "'Er war ein Lehrer.' Heinrich Julius Bruns (1746–1794). Beiträge des Reckahner Kolloquiums anlässlich seines 200. Todestages." In: Hanno Schmitt und Frank Tosch (Ed.): Quellen und Studien zur Berlin-Brandenburgischen Bildungsgeschichte, Vol. 2, Potsdam 1995. ISSN 0946-8897 (Studies about the Prussian educational history, Colloquium in Reckahn on the bicentenary of Bruns 1995)

- ^ Ellwood Cubberley, The History of Education: Educational Practice and Progress Considered as a Phase of the Development and Spread of Western Civilization (1920) online

- ^ Absolutistischer Staat und Schulwirklichkeit in Brandenburg-Preussen Wolfgang Neugebauer Walter de Gruyter, 1 January 1985

- ^ John Franklin Brown (1911). The Training of Teachers for Secondary Schools in Germany and the United States. Macmillan. pp. 21–25.

- ^ An Economic History of the United States: From 1607 to the Present, Ronald Seavoy, Routledge, 18 October 2013

- ^ Karl A. Schleunes, "Enlightenment, reform, reaction: the schooling revolution in Prussia." Central European History 12.4 (1979): 315-342 online.

- ^ Charles E. McClelland, State, society, and university in Germany: 1700-1914 (1980).

- ^ Mitchell G. Ash, "Bachelor of What, Master of Whom? The Humboldt Myth and Historical Transformations of Higher Education in German‐Speaking Europe and the U.S." European Journal of Education 41.2 (2006): 245-267 online.

- ^ Aneta Niewęgłowska, "Secondary Schools for Girls in Western Prussia, 1807-1911." Acta Poloniae Historica 99 (2009): 137-160.

- ^ Jeismann, Karl-Ernst. "American observations concerning the Prussian educational system in the nineteenth century." in Henry Geitz and Jürgen Heideking, eds. German influences on education in the United States to 1917 (2006) pp. 21–41.

- ^ Japan and Germany under the U.S. Occupation: A Comparative Analysis of Post-War Education Reform, Masako Shibata, Lexington Books, 20 September 2005

- ^ Eduard Spranger: Wilhelm von Humboldt und die Reform des Bildungswesens, Reuther u. Reichard, Berlin 1910

- ^ Cubberley, 1920

- ^ Sagarra, p 179

- ^ Addresses to the German Nation, 1807. Second Address: "The General Nature of the New Education". Chicago and London, The Open Court Publishing Company, 1922, p. 21

- ^ Leo Wieland: Katalonien – Kulturnation ohne Staat. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 10. Oktober 2007

- ^ Sport and Physical Education in Germany Ken Hardman, Roland Naul Routledge, 26 July 2005

- ^ Goodbody, John (1982). The Illustrated History of Gymnastics. London: Stanley Paul & Co. ISBN 0-09-143350-9.

- ^ Sprachliche Minderheiten und nationale Schule in Preußen zwischen 1871 und 1933 (Language minorities in Prussia between 1871 and 1933) Ferdinand Knabe Waxmann Verlag

- ^ a b Was gehen uns »die anderen« an?: Schule und Religion in der Säkularität (Why care about the others, School systems in secular-minded societies) Henning Schluß, Michael Domsgen, Matthias Spenn, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 15 August 2012

- ^ a b c d Deutschland, deine Lehrer: Warum sich die Zukunft unserer Kinder im Klassenzimmer entscheidet (Germany, your teachers; why the future of our children is being decided in the classroom) Christine Eichel Karl Blessing Verlag, 31 March 2014

- ^ Das Schulmeisterlein – Aus dem Leben des Volksschullehrers im 19. Jahrhundert, Exhibition on 19th-century teaching in Lohr am Main school museum, 20 May 2012

- ^ Georg Seeßlen, 1994: Die Feuerzangenbowle In: epd Film 3/94.

- ^ a b Citizenship, Education and the Modern State, Kerry J. Kennedy, Psychology Press, 1997

- ^ a b Körper und Geist von Format – Über die Heranbildung eines nützlichen und gelehrigen Gesellschaftskörpers: Seit der Implementierung des staatlich organisierten Schulunterrichts 1774 in der monarchia austriaca Verena Lesnik-Schobesberger, Austrian Diploma thesis published BoD 2009

- ^ Cubberley, 1920

- ^ Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal, and David Strang, "Construction of the First Mass Education Systems in Nineteenth-Century Europe," Sociology of Education (1989) 62#4 pp. 277–288 in JSTOR

- ^ Wilhelm von Humboldt, Franz-Michael Konrad UTB, 21 July 2010

- ^ Mark Groen, "The Whig Party and the Rise of Common Schools, 1837–1854," American Educational History Journal Spring/Summer 2008, Vol. 35 Issue 1/2, pp 251–260

- ^ Phillips, David; Ochs, Kimberly (December 2004). "Researching policy borrowing: Some methodological challenges in comparative education". British Educational Research Journal. 30 (6): 773–784. doi:10.1080/0141192042000279495.

- ^ a b Democratizing Education and Educating Democratic Citizens: International and Historical Perspectives Leslie J. Limage Routledge, 8 October 2013

- ^ Hegel at Stanford.edu

- ^ See Thomas Nipperdey, Deutsche Geschichte 1866–1918, Volume Arbeitswelt und Bürgergeist.

- ^ Andrew Donsion, "The Teenagers' Revolution: Schülerräte in the Democratization and Right-Wing Radicalization of Germany, 1918–1923," Central European History (2011) 44#3 pp 420–446.

- ^ a b Peter Braune: Die gescheiterte Einheitsschule. Heinrich Schulz. Parteisoldat zwischen Rosa Luxemburg und Friedrich Ebert. Karl-Dietz-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-320-02056-0

- ^ a b James F. Tent, "American Influences on the German Educational System", in The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945–1968, edited by Detlef Junker, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Publications of the German Historical Institute, 2004), pp. 394-400.

- ^ a b Zeitgeschichte Opfer der Umstände, Der Spiegel article from 1983 referring to James F. Tent [de], Mission on the Rhine: reeducation and denazification in American-occupied Germany. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1982

- ^ "CESifo Group Munich – Home". Cesifo-group.de. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ "German school system reflects nineteenth century". Justlanded.com. 2007-06-19. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ PISA Under Examination: Changing Knowledge, Changing Tests, and Changing Schools, Miguel A. Pereyra, Hans-Georg Kotthoff, Robert Cowen Springer Science & Business Media, 24 March 2012

Further reading[edit]

- Albisetti, James C. "The Reform of Female Education in Prussia, 1899-1908: A Study in Compromise and Containment." German studies review 8.1 (1985): 11–41.

- Ash, Mitchell G. "Bachelor of What, Master of Whom? The Humboldt Myth and Historical Transformations of Higher Education in German‐Speaking Europe and the U.S." European Journal of Education 41.2 (2006): 245-267 online.

- Becker, Sascha O., and Ludger Woessmann. "Luther and the girls: Religious denomination and the female education gap in nineteenth‐century Prussia." Scandinavian Journal of Economics 110.4 (2008): 777-805.

- Cubberley, Ellwood Patterson. The History of Education: Educational Practice and Progress Considered as a Phase of the Development and Spread of Western Civilization (1920) online

- Herbst, Jurgen. "Nineteenth‐Century Schools between Community and State: The Cases of Prussia and the United States." History of Education Quarterly 42.3 (2002): 317–341.

- McClelland, Charles E. State, society, and university in Germany: 1700-1914 (1980)

- McClelland, Charles E. Berlin, the Mother of All Research Universities: 1860–1918 (2016)

- Müller, Detlef, Fritz Ringer, and Brian Simon, eds. The rise of the modern educational system: structural change and social reproduction 1870–1920 (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- Phillips, David. "Beyond travellers' tales: some nineteenth-century British commentators on education in Germany." Oxford Review of Education 26.1 (2000): 49–62.

- Ramsay, Paul. "Toiling together for social cohesion: International influences on the development of teacher education in the United States," Paedagogica Historica (2014) 50#1 pp 109–122.

- Ringer, Fritz. Education and Society in Modern Europe (1979); focus on Germany and France with comparisons to US and Britain

- Sagarra, Eda. A Social History of Germany, 1648–1914 (1977) online

- Schleunes, Karl A. "Enlightenment, reform, reaction: the schooling revolution in Prussia." Central European History 12.4 (1979): 315-342 online

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoglu, and David Strang. "Construction of the First Mass Education Systems in Nineteenth-Century Europe," Sociology of Education (1989) 62#4 pp. 277–288 in JSTOR

- Turner, R. Steven. "The growth of professorial research in Prussia, 1818 to 1848-causes and context." Historical studies in the physical sciences 3 (1971): 137–182.

- Van Horn Melton, James. Absolutism and the eighteenth-century origins of compulsory schooling in Prussia and Austria (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Primary sources[edit]

- Cubberley, Ellwood Patterson ed. Readings in the History of Education: A Collection of Sources and Readings to Illustrate the Development of Educational Practice, Theory, and Organization (1920) online pp 455–89, 634ff, 669ff