Sakhalin

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (March 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Russian Far East,[1] Northern Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 51°N 143°E / 51°N 143°E |

| Area | 72,492 km2 (27,989 sq mi)[2] |

| Area rank | 23rd |

| Highest elevation | 1,609 m (5279 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Lopatin |

| Administration | |

Russia[1] | |

| Federal subject | Sakhalin Oblast |

| Largest settlement | Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (pop. 174,203) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 489,638 (2019) |

| Pop. density | 6/km2 (16/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | majority Russians, some Nivkh, Orok, Ainu, Japanese & Sakhalin Koreans |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

Sakhalin (Russian: Сахалин, IPA: [səxɐˈlʲin]) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies 6.5 km (4.0 mi) off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Japan's Hokkaido. A marginal island of the West Pacific, Sakhalin divides the Sea of Okhotsk to its east from the Sea of Japan to its southwest. It is administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast and is the largest island of Russia,[3] with an area of 72,492 square kilometres (27,989 sq mi). The island has a population of roughly 500,000, the majority of whom are Russians. The indigenous peoples of the island are the Ainu, Oroks, and Nivkhs, who are now present in very small numbers.[4]

The island's name is derived from the Manchu word Sahaliyan (ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ). The Ainu people of Sakhalin paid tribute to the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties and accepted official appointments from them. Sometimes the relationship was forced but control from dynasties in China was loose for the most part.[5][6] Sakhalin was later claimed by both Russia and Japan over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. These disputes sometimes involved military conflicts and divisions of the island between the two powers. In 1875, Japan ceded its claims to Russia in exchange for the northern Kuril Islands. In 1905, following the Russo-Japanese War, the island was divided, with Southern Sakhalin going to Japan. Russia has held all of the island since seizing the Japanese portion in the final days of World War II in 1945, as well as all of the Kurils. Japan no longer claims any of Sakhalin, although it does still claim the southern Kuril Islands. Most Ainu on Sakhalin moved to Hokkaido, 43 kilometres (27 mi) to the south across the La Pérouse Strait, when Japanese civilians were displaced from the island in 1949.[7]

Etymology[edit]

Sakhalin has several names including Karafuto (Japanese: 樺太, Karafuto), Kuye (simplified Chinese: 库页岛; traditional Chinese: 庫頁島; pinyin: Kùyèdǎo), Sahaliyan (Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ), Bugata nā (Orok: Бугата на̄), Yh-mif (Nivkh: Ых-миф).

The Manchus called it "Sahaliyan ula angga hada" (Island at the Mouth of the Black River) ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᡠᠯᠠ ᠠᠩᡤᠠ

ᡥᠠᡩᠠ.[8] Sahaliyan, the word that has been borrowed in the form of "Sakhalin", means "black" in Manchu, ula means "river" and sahaliyan ula (ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᡠᠯᠠ, "Black River") is the proper Manchu name of the Amur River.

The Qing dynasty called Sakhalin ‘Kuyedao’ (‘the island of Ainu’) and the indigenous people paid tribute to the Chinese empire. However, there was no formalized border around the island. The Qing dynasty was a pre- modern or ‘world empire’ which did not place emphasis on demarcating borders in the manner of the modern ‘national empires’ of the nineteenth and early twentieth century (Yamamuro 2003: 90–97).[9]

— T. Nakayama

The island was also called "Kuye Fiyaka".[10] The word "Kuye" used by the Qing is "most probably related to kuyi, the name given to the Sakhalin Ainu by their Nivkh and Nanai neighbors."[11] When the Ainu migrated onto the mainland, the Chinese described a "strong Kui (or Kuwei, Kuwu, Kuye, Kugi, i.e. Ainu) presence in the area otherwise dominated by the Gilemi or Jilimi (Nivkh and other Amur peoples)."[12] Related names were in widespread use in the region, for example the Kuril Ainu called themselves koushi.[11]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the Neolithic Stone Age. Flint implements such as those found in Siberia have been found at Dui and Kusunai in great numbers, as well as polished stone hatchets similar to European examples, primitive pottery with decorations like those of the Olonets, and stone weights used with fishing nets. A later population familiar with bronze left traces in earthen walls and kitchen-middens on Aniva Bay.

Indigenous people of Sakhalin include the Ainu in the southern half, the Oroks in the central region, and the Nivkhs in the north.[13][page needed]

Yuan and Ming tributaries[edit]

After the Mongols conquered the Jin dynasty (1234), they suffered raids by the Nivkh and Udege peoples. In response, the Mongols established an administration post at Nurgan (present-day Tyr, Russia) at the junction of the Amur and Amgun rivers in 1263, and forced the submission of the two peoples.[14]

From the Nivkh perspective, their surrender to the Mongols essentially established a military alliance against the Ainu who had invaded their lands.[15] According to the History of Yuan, a group of people known as the Guwei (骨嵬; Gǔwéi, the Nivkh name for Ainu) from Sakhalin invaded and fought with the Jilimi (Nivkh people) every year. On 30 November 1264, the Mongols attacked the Ainu.[16] The Ainu resisted the Mongol invasions but by 1308 had been subdued. They paid tribute to the Mongol Yuan dynasty at posts in Wuliehe, Nanghar, and Boluohe.[17]

The Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) placed Sakhalin under its "system for subjugated peoples" (ximin tizhi). From 1409 to 1411 the Ming established an outpost called the Nurgan Regional Military Commission near the ruins of Tyr on the Siberian mainland, which continued operating until the mid-1430s. There is some evidence that the Ming eunuch Admiral Yishiha reached Sakhalin in 1413 during one of his expeditions to the lower Amur, and granted Ming titles to a local chieftain.[18]

The Ming recruited headmen from Sakhalin for administrative posts such as commander (指揮使; zhǐhuīshǐ), assistant commander (指揮僉事; zhǐhuī qiānshì), and "official charged with subjugation" (衛鎮撫; wèizhènfǔ). In 1431, one such assistant commander, Alige, brought marten pelts as tribute to the Wuliehe post. In 1437, four other assistant commanders (Zhaluha, Sanchiha, Tuolingha, and Alingge) also presented tribute. According to the Ming Veritable Records, these posts, like the position of headman, were hereditary and passed down the patrilineal line. During these tributary missions, the headmen would bring their sons, who later inherited their titles. In return for tribute, the Ming awarded them with silk uniforms.[17]

Nivkh women in Sakhalin married Han Chinese Ming officials when the Ming took tribute from Sakhalin and the Amur river region.[19][20]

Qing tributary[edit]

The Manchu Qing dynasty, which came to power in China in 1644, called Sakhalin "Kuyedao" (Chinese: 库页岛; pinyin: Kùyè dǎo; lit. 'island of the Ainu')[21][22][9] or "Kuye Fiyaka" (ᡴᡠᠶᡝ

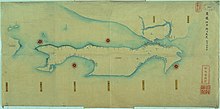

ᡶᡳᠶᠠᡴᠠ).[10] The Manchus called it "Sagaliyan ula angga hada" (Island at the Mouth of the Black River).[8] The Qing first asserted influence over Sakhalin after the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, which defined the Stanovoy Mountains as the border between the Qing and the Russian Empires. In the following year the Qing sent forces to the Amur estuary and demanded that the residents, including the Sakhalin Ainu, pay tribute. This was followed by several further visits to the island as part of the Qing effort to map the area. To enforce its influence, the Qing sent soldiers and mandarins across Sakhalin, reaching most parts of the island except the southern tip. The Qing imposed a fur-tribute system on the region's inhabitants.[23][24][20]

The Qing dynasty ruled these regions by imposing upon them a fur tribute system, just as had the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Residents who were required to pay tributes had to register according to their hala (ᡥᠠᠯᠠ, the clan of the father's side) and gashan (ᡤᠠᡧᠠᠨ, village), and a designated chief of each unit was put in charge of district security as well as the annual collection and delivery of fur. By 1750, fifty-six hala and 2,398 households were registered as fur tribute payers, – those who paid with fur were rewarded mainly with Nishiki silk brocade, and every year the dynasty supplied the chief of each clan and village with official silk clothes (mangpao, duanpao), which were the gowns of the mandarin. Those who offered especially large fur tributes were granted the right to create a familial relationship with officials of the Manchu Eight Banners (at the time equivalent to Chinese aristocrats) by marrying an official's adopted daughter. Further, the tribute payers were allowed to engage in trade with officials and merchants at the tribute location. By these policies, the Qing dynasty brought political stability to the region and established the basis for commerce and economic development.[24]

— Shiro Sasaki

The Qing dynasty established an office in Ningguta, situated midway along the Mudan River, to handle fur from the lower Amur and Sakhalin. Tribute was supposed to be brought to regional offices, but the lower Amur and Sakhalin were considered too remote, so the Qing sent officials directly to these regions every year to collect tribute and to present awards. By the 1730s, the Qing had appointed senior figures among the indigenous communities as "clan chief" (hala-i-da) or "village chief" (gasan-da or mokun-da). In 1732, 6 hala, 18 gasban, and 148 households were registered as tribute bearers in Sakhalin. Manchu officials gave tribute missions rice, salt, other necessities, and gifts during the duration of their mission. Tribute missions occurred during the summer months. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–95), a trade post existed at Delen, upstream of Kiji (Kizi) Lake, according to Rinzo Mamiya. There were 500–600 people at the market during Mamiya's stay there.[25][20]

Local native Sakhalin chiefs had their daughters taken as wives by Manchu officials as sanctioned by the Qing dynasty when the Qing exercised jurisdiction in Sakhalin and took tribute from them.[26][20]

Japanese exploration and colonization[edit]

In 1635 Matsumae Kinhiro, the second daimyō of Matsumae Domain in Hokkaidō, sent Satō Kamoemon and Kakizaki Kuroudo on an expedition to Sakhalin. One of the Matsumae explorers, Kodō Shōzaemon, stayed in the island in the winter of 1636 and sailed along the east coast to Taraika (now Poronaysk) in the spring of 1637.[27]

In an early colonization attempt, a Japanese settlement was established at Ōtomari on Sakhalin's southern end in 1679.[28] Cartographers of the Matsumae clan drew a map of the island and called it "Kita-Ezo" (Northern Ezo, Ezo being the old Japanese name for the islands north of Honshu).

In the 1780s the influence of the Japanese Tokugawa Shogunate on the Ainu of southern Sakhalin increased significantly. By the beginning of the 19th century, the Japanese economic zone extended midway up the east coast, to Taraika. With the exception of the Nayoro Ainu located on the west coast in close proximity to China, most Ainu stopped paying tribute to the Qing dynasty. The Matsumae clan was nominally in charge of Sakhalin, but they neither protected nor governed the Ainu there. Instead they extorted the Ainu for Chinese silk, which they sold in Honshu as Matsumae's special product. To obtain Chinese silk, the Ainu fell into debt, owing much fur to the Santan (Ulch people), who lived near the Qing office. The Ainu also sold the silk uniforms (mangpao, bufu, and chaofu) given to them by the Qing, which made up the majority of what the Japanese knew as nishiki and jittoku. As dynastic uniforms, the silk was of considerably higher quality than that traded at Nagasaki, and enhanced Matsumae prestige as exotic items.[23] Eventually the Tokugawa government, realizing that they could not depend on the Matsumae, took control of Sakhalin in 1807.[29]

Mogami's interest in the Sakhalin trade intensified when he learned that Yaenkoroaino, the above-mentioned elder from Nayoro, possessed a memorandum written in Manchurian, which stated that the Ainu elder was an official of the Qing state. Later surveys on Sakhalin by shogunal officials such as Takahashi Jidayú and Nakamura Koichiró only confirmed earlier observations: Sakhalin and Sóya Ainu traded foreign goods at trading posts, and because of the pressure to meet quotas, they fell into debt. These goods, the officials confirmed, originated at Qing posts, where continental traders acquired them during tributary ceremonies. The information contained in these types of reports turned out to be a serious blow to the future of Matsumae's trade monopoly in Ezo.[30]

— Brett L. Walker

Japan proclaimed sovereignty over Sakhalin in 1807, and in 1809 Mamiya Rinzō claimed that it was an island.[31]

European exploration[edit]

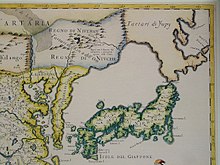

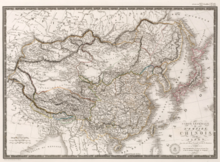

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The Dutch captain, however, was unaware that it was an island, and 17th-century maps usually showed these points (and often Hokkaido as well) as part of the mainland. As part of a nationwide Sino-French cartographic program, Jesuits Jean-Baptiste Régis, Pierre Jartoux, and Xavier Ehrenbert Fridelli joined a Chinese team visiting the lower Amur (known to them under its Manchu name, Sahaliyan Ula, "the Black River"), in 1709,[32] and learned of the existence of the nearby offshore island from the Nanai natives of the lower Amur.[33]

The Jesuits did not have a chance to visit the island, and the geographical information provided by the Nanai people and Manchus who had been to the island was insufficient to allow them to identify it as the land visited by de Vries in 1643. As a result, many 17th-century maps showed a rather strangely shaped Sakhalin, which included only the northern half of the island (with Cape Patience), while Cape Aniva, discovered by de Vries, and the "Black Cape" (Cape Crillon) were thought to form part of the mainland.[citation needed]

Only with the 1787 expedition of Jean-François de La Pérouse did the island began to resemble something of its true shape on European maps. Though unable to pass through its northern "bottleneck" due to contrary winds, La Perouse charted most of the Strait of Tartary, and islanders he encountered near today's Nevelskoy Strait told him that the island was called "Tchoka" (or at least that is how he recorded the name in French), and "Tchoka" appears on some maps thereafter.[34]

19th century[edit]

Russo-Japanese rivalry[edit]

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the Kuril Islands chain) in 1845, in the face of competing claims from Russia. In 1849, however, the Russian navigator Gennady Nevelskoy recorded the existence and navigability of the strait later given his name, and Russian settlers began establishing coal mines, administration facilities, schools, and churches on the island. In 1853–54, Nikolay Rudanovsky surveyed and mapped the island.[35]

In 1855, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimoda, which declared that nationals of both countries could inhabit the island: Russians in the north, and Japanese in the south, without a clearly defined boundary between. Russia also agreed to dismantle its military base at Ootomari. Following the Second Opium War, Russia forced China to sign the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Convention of Peking (1860), under which China lost to Russia all claims to territories north of Heilongjiang (Amur) and east of Ussuri.

In 1857, the Russians established a penal colony on Sakhalin.[36] The island remained under shared sovereignty until the signing of the 1875 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, in which Japan surrendered its claims in Sakhalin to Russia. In 1890 the author Anton Chekhov visited the penal colony on Sakhalin and published a memoir of his journey.[37]

Division along 50th parallel[edit]

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the Russo-Japanese War. In accordance with the Treaty of Portsmouth of 1905, the southern part of the island below the 50th parallel north reverted to Japan, while Russia retained the northern three-fifths. In 1920, during the Siberian Intervention, Japan again occupied the northern part of the island, returning it to the Soviet Union in 1925.

South Sakhalin was administered by Japan as Karafuto Prefecture (Karafuto-chō (樺太庁)), with the capital at Toyohara (today's Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk). A large number of migrants were brought in from Korea.[citation needed]

The northern, Russian, half of the island formed Sakhalin Oblast, with the capital at Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalinsky.[citation needed]

Whaling[edit]

Between 1848 and 1902, American whaleships hunted whales off Sakhalin.[38] They cruised for bowhead and gray whales to the north and right whales to the east and south.[39]

On June 7, 1855, the ship Jefferson (396 tons), of New London, was wrecked on Cape Levenshtern, on the northeastern side of the island, during a fog. All hands were saved as well as 300 barrels of whale oil.[40][41][42]

Second World War[edit]

In August 1945, after repudiating the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, the Soviet Union invaded southern Sakhalin, an action planned secretly at the Yalta Conference. The Soviet attack started on August 11, 1945, a few days before the surrender of Japan. The Soviet 56th Rifle Corps, part of the 16th Army, consisting of the 79th Rifle Division, the 2nd Rifle Brigade, the 5th Rifle Brigade and the 214 Armored Brigade,[43] attacked the Japanese 88th Infantry Division. Although the Soviet Red Army outnumbered the Japanese by three to one, they advanced only slowly due to strong Japanese resistance. It was not until the 113th Rifle Brigade and the 365th Independent Naval Infantry Rifle Battalion from Sovetskaya Gavan landed on Tōro, a seashore village of western Karafuto, on August 16 that the Soviets broke the Japanese defense line. Japanese resistance grew weaker after this landing. Actual fighting continued until August 21. From August 22 to August 23, most remaining Japanese units agreed to a ceasefire. The Soviets completed the conquest of Karafuto on August 25, 1945, by occupying the capital of Toyohara.[citation needed]

Of the approximately 400,000 people – mostly Japanese and Korean – who lived on South Sakhalin in 1944, about 100,000 were evacuated to Japan during the last days of the war. The remaining 300,000 stayed behind, some for several more years.[44]

While the vast majority of Sakhalin Japanese and Koreans were gradually repatriated between 1946 and 1950, tens of thousands of Sakhalin Koreans (and a number of their Japanese spouses) remained in the Soviet Union.[45][46]

No final peace treaty has been signed and the status of four neighboring islands remains disputed. Japan renounced its claims of sovereignty over southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Treaty of San Francisco (1951), but maintains that the four offshore islands of Hokkaido currently administered by Russia were not subject to this renunciation.[47] Japan granted mutual exchange visas for Japanese and Ainu families divided by the change in status. Recently, economic and political cooperation has gradually improved between the two nations despite disagreements.[48]

Recent history[edit]

On 1 September 1983, Korean Air Flight 007, a South Korean civilian airliner, flew over Sakhalin and was shot down by the Soviet Union, just west of Sakhalin Island, near the smaller Moneron Island. The Soviet Union claimed it was a spy plane; however, commanders on the ground realized it was a commercial aircraft. All 269 passengers and crew died, including a U.S. Congressman, Larry McDonald.[citation needed]

On 27 May 1995, the 7.0 Mw Neftegorsk earthquake shook the former Russian settlement of Neftegorsk with a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent). Total damage was $64.1–300 million, with 1,989 deaths and 750 injured. The settlement was not rebuilt.[citation needed]

Geography[edit]

Sakhalin is separated from the mainland by the narrow and shallow Strait of Tartary, which often freezes in winter in its narrower part, and from Hokkaido, Japan, by the Soya Strait or La Pérouse Strait. Sakhalin is the largest island in Russia, being 948 km (589 mi) long, and 25 to 170 km (16 to 106 mi) wide, with an area of 72,492 km2 (27,989 sq mi).[2] It lies at similar latitudes to England, Wales and Ireland.

Its orography and geological structure are imperfectly known. One theory is that Sakhalin arose from the Sakhalin Island Arc.[49] Nearly two-thirds of Sakhalin is mountainous. Two parallel ranges of mountains traverse it from north to south, reaching 600–1,500 m (2,000–4,900 ft). The Western Sakhalin Mountains peak in Mount Ichara, 1,481 m (4,859 ft), while the Eastern Sakhalin Mountains's highest peak, Mount Lopatin 1,609 m (5,279 ft), is also the island's highest mountain. Tym-Poronaiskaya Valley separates the two ranges. Susuanaisky and Tonino-Anivsky ranges traverse the island in the south, while the swampy Northern-Sakhalin plain occupies most of its north.[50]

Crystalline rocks crop out at several capes; Cretaceous limestones, containing an abundant and specific fauna of gigantic ammonites, occur at Dui on the west coast; and Tertiary conglomerates, sandstones, marls, and clays, folded by subsequent upheavals, are found in many parts of the island. The clays, which contain layers of good coal and abundant fossilized vegetation, show that during the Miocene period, Sakhalin formed part of a continent which comprised north Asia, Alaska, and Japan, and enjoyed a comparatively warm climate. The Pliocene deposits contain a mollusc fauna more Arctic than that which exists at the present time, indicating that the connection between the Pacific and Arctic Oceans was probably broader than it is now.

Main rivers: The Tym, 330 km (205 mi) long and navigable by rafts and light boats for 80 km (50 mi), flows north and northeast with numerous rapids and shallows, and enters the Sea of Okhotsk.[51] The Poronay flows south-southeast to the Gulf of Patience or Shichiro Bay, on the southeastern coast. Three other small streams enter the wide semicircular Aniva Bay or Higashifushimi Bay at the southern extremity of the island.

The northernmost point of Sakhalin is Cape of Elisabeth on the Schmidt Peninsula, while Cape Crillon is the southernmost point of the island.

Sakhalin has two smaller islands associated with it, Moneron Island and Ush Island. Moneron, the only land mass in the Tatar strait, 7.2 km (4.5 mi) long and 5.6 km (3.5 mi) wide, is about 24 nautical miles (44 km) west from the nearest coast of Sakhalin and 41 nmi (76 km) from the port city of Nevelsk. Ush Island is an island off of the northern coast of Sakhalin.

-

Sakhalin and its surroundings.

-

Velikan Cape, Sakhalin

-

Zhdanko Mountain Ridge

Demographics[edit]

According to the 1897 census, Sakhalin had a population of 28,113, of which 56.2% were Russians, 8.4% Ukrainians, 7.0% Nivkh, 5.8% Poles, 5.4% Tatars, 5.1% Ainu, 2.82% Oroks, 0.95% Germans, 0.81% Japanese, with the non-indigenous people living mainly from agriculture, or being convicts or exiles.[52] The majority of Nivkh, Ainu and Japanese lived from fishing or hunting, whereas the Oroks lived mainly by livestock breeding.[53] The Ainu, Japanese and Koreans lived almost exclusively in the southern part of the island.[54] Since 1925, many Poles fled Soviet Russian persecution in the north to the then Japanese south.[55]

In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic Russians, followed by about 30,000 Koreans (5.5%). Smaller minorities were the Ainu, Ukrainians, Tatars, Sakhas and Evenks. The native inhabitants currently consist of some 2,000 Nivkhs and 750 Oroks. The Nivkhs in the north support themselves by fishing and hunting. In 2008 there were 6,416 births and 7,572 deaths.[56]

The administrative center of the oblast, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, a city of about 175,000, has a large Korean minority, typically referred to as Sakhalin Koreans, who were forcibly brought by the Japanese during World War II to work in the coal mines. Most of the population lives in the southern half of the island, centered mainly around Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and two ports, Kholmsk and Korsakov (population about 40,000 each).

The 400,000 Japanese inhabitants of Sakhalin (including the Japanized indigenous Ainu) who had not already been evacuated during the war were deported following the invasion of the southern portion of the island by the Soviet Union in 1945 at the end of World War II.[57]

Climate[edit]

| Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Sea of Okhotsk ensures that Sakhalin has a cold and humid climate, ranging from humid continental (Köppen Dfb) in the south to subarctic (Dfc) in the centre and north. The maritime influence makes summers much cooler than in similar-latitude inland cities such as Harbin or Irkutsk, but makes the winters much snowier and a few degrees warmer than in interior East Asian cities at the same latitude. Summers are foggy with little sunshine.[58][failed verification]

Precipitation is heavy, owing to the strong onshore winds in summer and the high frequency of North Pacific storms affecting the island in the autumn. It ranges from around 500 millimetres (20 in) on the northwest coast to over 1,200 millimetres (47 in) in southern mountainous regions. In contrast to interior east Asia with its pronounced summer maximum, onshore winds ensure Sakhalin has year-round precipitation with a peak in the autumn.[50]

Flora and fauna[edit]

The whole of the island is covered with dense forests, mostly coniferous. The Yezo (or Yeddo) spruce (Picea jezoensis), the Sakhalin fir (Abies sachalinensis) and the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) are the chief trees; on the upper parts of the mountains are the Siberian dwarf pine (Pinus pumila) and the Kurile bamboo (Sasa kurilensis). Birches, both Siberian silver birch (Betula platyphylla) and Erman's birch (B. ermanii), poplar, elm, bird cherry (Prunus padus), Japanese yew (Taxus cuspidata), and several willows are mixed with the conifers; while farther south the maple, rowan and oak, as also the Japanese Panax ricinifolium, the Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense), the spindle (Euonymus macropterus) and the vine (Vitis thunbergii) make their appearance. The underwoods abound in berry-bearing plants (e.g. cloudberry, cranberry, crowberry, red whortleberry), red-berried elder (Sambucus racemosa), wild raspberry, and spiraea.

Brown bear, Eurasian river otter, red fox and sable are fairly numerous (as are reindeer in the north); rarely seen, but still present, is the elusive Sakhalin musk deer, a subspecies of Siberian musk deer. Smaller mammals include hare, squirrels, and various rodents (including rats and mice) nearly everywhere. The bird population is made-up of mostly the common eastern Siberian forms, but there are some endemic or near-endemic breeding species, notably the endangered Nordmann's greenshank (Tringa guttifer) and the Sakhalin leaf warbler (Phylloscopus borealoides). The rivers swarm with fish, especially species of salmon (Oncorhynchus). Numerous cetaceans visit the sea coast, including the critically endangered Western Pacific gray whale, for which the waters off of Sakhalin are their only known feeding ground, thus being a vitally important region for their population's longevity. Other cetaceans known to occur in this area are the North Pacific right whale, the bowhead whale, and the beluga whale, the latter two generally preferring icy waters and colder conditions to the north. All are potential prey species for the highly social killer whale, or orca. The once-common Japanese sea lion and Japanese sea otter, both hunted to extinction, formerly ranged from Japan's coastline to Sakhalin, Korea, Kamchatka, and the Yellow Sea; however, over-harvesting depleted their numbers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today, ringed seals and the giant Steller sea lion can be spotted around Sakhalin Island.

Transport[edit]

Sea[edit]

Transport, especially by sea, is an important segment of the economy. Nearly all the cargo arriving for Sakhalin (and the Kuril Islands) is delivered by cargo boats, or by ferries, in railway wagons, through the Vanino-Kholmsk train ferry from the mainland port of Vanino to Kholmsk. The ports of Korsakov and Kholmsk are the largest and handle all kinds of goods, while coal and timber shipments often go through other ports. In 1999, a ferry service was opened between the ports of Korsakov and Wakkanai, Japan, and operated through the autumn of 2015, when service was suspended.

For the 2016 summer season, this route will be served by a highspeed catamaran ferry from Singapore named Penguin 33. The ferry is owned by Penguin International Limited[59] and operated by Sakhalin Shipping Company.[60]

Sakhalin's main shipping company is Sakhalin Shipping Company, headquartered in Kholmsk on the island's west coast.

Rail[edit]

About 30% of all inland transport volume is carried by the island's railways, most of which are organized as the Sakhalin Railway (Сахалинская железная дорога), which is one of the 17 territorial divisions of the Russian Railways.

The Sakhalin Railway network extends from Nogliki in the north to Korsakov in the south. Sakhalin's railway has a connection with the rest of Russia via a train ferry operating between Vanino and Kholmsk.

The process of converting the railways from the Japanese 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge to the Russian 1,520 mm (4 ft 11+27⁄32 in) gauge began in 2004[61][62] and was completed in 2019.[63] The original Japanese D51 steam locomotives were used by the Soviet Railways until 1979.

Besides the main network run by the Russian Railways, until December 2006 the local oil company (Sakhalinmorneftegaz) operated a corporate narrow-gauge 750 mm (2 ft 5+1⁄2 in) line extending for 228 kilometers (142 mi) from Nogliki further north to Okha (Узкоколейная железная дорога Оха – Ноглики). During the last years of its service, it gradually deteriorated; the service was terminated in December 2006, and the line was dismantled in 2007–2008.[64]

-

A passenger train in Nogliki

-

A Japanese D51 steam locomotive outside the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Railway Station

Air[edit]

Sakhalin is connected by regular flights to Moscow, Khabarovsk, Vladivostok and other cities of Russia. Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Airport has regularly scheduled international flights to Hakodate, Japan, and Seoul and Busan, South Korea. There are also charter flights to the Japanese cities of Tokyo, Niigata, and Sapporo and to the Chinese cities of Shanghai, Dalian and Harbin. The island was formerly served by Alaska Airlines from Anchorage, Petropavlovsk, and Magadan.

Fixed links[edit]

The idea of building a fixed link between Sakhalin and the Russian mainland was first put forward in the 1930s. In the 1940s, an abortive attempt was made to link the island via a 10-kilometre-long (6 mi) undersea tunnel.[65] The project was abandoned under Premier Nikita Khrushchev. In 2000, the Russian government revived the idea, adding a suggestion that a 40-km (25 mile) long bridge could be constructed between Sakhalin and the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, providing Japan with a direct connection to the Eurasian railway network. It was claimed that construction work could begin as early as 2001. The idea was received skeptically by the Japanese government and appears to have been shelved, probably permanently, after the cost was estimated at as much as $50 billion.

In November 2008, Russian president Dmitry Medvedev announced government support for the construction of the Sakhalin Tunnel, along with the required regauging of the island's railways to Russian standard gauge, at an estimated cost of 300–330 billion roubles.[66]

In July 2013, Russian Far East development minister Viktor Ishayev proposed a railway bridge to link Sakhalin with the Russian mainland. He also again suggested a bridge between Sakhalin and Hokkaidō, which could potentially create a continuous rail corridor between Europe and Japan.[67] In 2018, president Vladimir Putin ordered a feasibility study for a mainland bridge project.[citation needed]

Economy[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

Sakhalin is a classic "primary sector of the economy" area, relying on oil and gas exports, coal mining, forestry, and fishing. Limited quantities of rye, wheat, oats, barley and vegetables grow there, although the growing season averages less than 100 days.[50]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent economic liberalization, Sakhalin has experienced an oil boom with extensive petroleum-exploration and mining by most large oil multinational corporations. The oil and natural- gas reserves contain an estimated 14 billion barrels (2.2 km3) of oil and 2,700 km3 (96 trillion cubic feet) of gas and are being developed under production-sharing agreement contracts involving international oil- companies like ExxonMobil and Shell.

In 1996, two large consortia, Sakhalin-I and Sakhalin-II, signed contracts to explore for oil and gas off the northeast coast of the island. The two consortia's pre-project estimate of costs were a combined US$21 billion on the two projects; costs had almost doubled to $37 billion as of September 2006, triggering Russian governmental opposition. The cost will include an estimated US$1 billion to upgrade the island's infrastructure: roads, bridges, waste management sites, airports, railways, communications systems, and ports. In addition, Sakhalin-III-through-VI are in various early stages of development.

The Sakhalin I project, managed by Exxon Neftegas, completed a production-sharing agreement (PSA) between the Sakhalin I consortium, the Russian Federation, and the Sakhalin government. Russia is in the process of building a 220 km (140 mi) pipeline across the Tatar Strait from Sakhalin Island to De-Kastri terminal on the Russian mainland. From De-Kastri, the resource will be loaded onto tankers for transport to East Asian markets, namely Japan, South Korea and China.

A second consortium, Sakhalin Energy Investment Company Ltd (Sakhalin Energy), is managing the Sakhalin II project. It has completed the first production-sharing agreement (PSA) with the Russian Federation. Sakhalin Energy will build two 800-km pipelines running from the northeast of the island to Prigorodnoye (Prigorodnoe) in Aniva Bay at the southern end. The consortium will also build, at Prigorodnoye, the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant to be built in Russia. The oil and gas are also bound for East Asian markets.

Sakhalin II has come under fire from environmental groups, namely Sakhalin Environment Watch, for dumping dredging material in Aniva Bay. These groups were also worried about the offshore pipelines interfering with the migration of whales off the island. The consortium has (as of January 2006[update]) rerouted the pipeline to avoid the whale migration. After a doubling in the projected cost, the Russian government threatened to halt the project for environmental reasons.[68] There have been suggestions[by whom?] that the Russian government is using the environmental issues as a pretext for obtaining a greater share of revenues from the project and/or forcing involvement by the state-controlled Gazprom. The cost overruns (at least partly due to Shell's response to environmental concerns), are reducing the share of profits flowing to the Russian treasury.[69][70][71][72]

In 2000, the oil-and-gas industry accounted for 57.5% of Sakhalin's industrial output. By 2006 it is expected[by whom?] to account for 80% of the island's industrial output. Sakhalin's economy is growing rapidly thanks to its oil-and-gas industry.

As of 18 April 2007[update], Gazprom had taken a 50% plus one share interest in Sakhalin II by purchasing 50% of Shell, Mitsui and Mitsubishi's shares.

In June 2021, it was announced that Russia aims to make Sakhalin Island carbon neutral by 2025.[73]

International partnerships[edit]

- Gig Harbor, Washington, United States

- Jeju Province, South Korea

Claimed by[edit]

- Russian Empire 18th Century to 1875

- Tokugawa Shogunate, Empire of Japan 1840–1875

- Qing dynasty, 1636–1872

See also[edit]

- List of islands of Russia

- Ryugase Group – a geological formation on the island

- Winter storms of 2009–10 in East Asia

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "Sakhalin Island | island, Russia". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Islands by Land Area". Island Directory. United Nations Environment Program. February 18, 1998. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Ros, Miquel (January 2, 2019). "Russia's Far East opens up to visitors". CNN Travel. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Sakhalin Regional Museum: The Indigenous Peoples". Sakh.com. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Gan, Chunsong (2019). A Concise Reader of Chinese Culture. Springer. p. 24. ISBN 9789811388675.

- ^ Westad, Odd (2012). Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750. Basic Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780465029365.

- ^ Reid, Anna (2003). The Shaman's Coat: A Native History of Siberia. New York: Walker & Company. pp. 148–150. ISBN 0-8027-1399-8.

- ^ a b Narangoa 2014, p. 295.

- ^ a b Nakayama 2015, p. 20.

- ^ a b Schlesinger 2017, p. 135.

- ^ a b Hudson 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Zgusta 2015, p. 64.

- ^ Gall, Timothy L. (1998). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0-7876-0552-2.

- ^ Nakamura 2010, p. 415; Stephan 1971, p. 21.

- ^ Zgusta 2015, p. 96.

- ^ Nakamura 2010, p. 415.

- ^ a b Walker 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry (2002) [2001]. Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. Seattle, Wash: University of Washington Press. pp. 158–161. ISBN 0-295-98124-5. Retrieved June 16, 2010. Link is to partial text.

- ^ (Sei Wada, ‘The Natives of the Lower reaches of the Amur as Represented in Chinese Records’, Memoirs of the Research Department of Toyo Bunko, no. 10, 1938, pp. 40‒102) (Shina no kisai ni arawaretaru Kokuryuko karyuiki no dojin 支那の記載に現はれたる黒龍江下流域の土人( The natives on the lower reaches of the Amur river as represented in Chinese records), Tõagaku 5, vol . 1, Sept. 1939.) Wada, ‘Natives of the Lower Reaches of the Amur River’, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (November 15, 2020). "Indigenous Diplomacy: Sakhalin Ainu (Enchiw) in the Shaping of Modern East Asia (Part 1: Traders and Travellers)". Japan Focus: The Asia-Pacific Journal. 18 (22).

- ^ Smith 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Kim 2019, p. 81.

- ^ a b Walker 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Sasaki 1999, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Sasaki 1999, p. 87.

- ^ (Shiro Sasaki, ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities Between the Russian and Chinese Empires’, Senri Ethnological Studies, vol. 92, 2016, pp. 161‒193.) Sasaki, ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities’, p. 173.

- ^ 秋月俊幸『日露関係とサハリン島:幕末明治初年の領土問題』筑摩書房、1994年、34頁(Akizuki Toshiyuki, Nich-Ro kankei to Saharintō : Bakumatsu Meiji shonen no ryōdo mondai (Japanese–Russian Relations and Sakhalin Island: Territorial Dispute in the Bakumatsu and First Meiji Years), (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo Publishers Ltd), p. 34. ISBN 4480856684)

- ^ "Time Table of Sakhalin Island". Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Sasaki 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Walker 2006, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Lower, Arthur (1978). Ocean of Destiny: A concise History of the North Pacific, 1500–1978. UBC. p. 75. ISBN 9780774843522.

- ^ Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1736). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique, et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise, enrichie des cartes générales et particulieres de ces pays, de la carte générale et des cartes particulieres du Thibet, & de la Corée; & ornée d'un grand nombre de figures & de vignettes gravées en tailledouce. Vol. 1. La Haye: H. Scheurleer. p. xxxviii. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1736). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique, et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise, enrichie des cartes générales et particulieres de ces pays, de la carte générale et des cartes particulieres du Thibet, & de la Corée; & ornée d'un grand nombre de figures & de vignettes gravées en tailledouce. Vol. 4. La Haye: H. Scheurleer. pp. 14–16. Retrieved June 16, 2010. The people whose name the Jesuits recorded as Ke tcheng ta tse ("Hezhen Tatars") lived, according to the Jesuits, on the Amur below the mouth of the Dondon River, and were related to the Yupi ta tse ("Fishskin Tatars") living on the Ussuri and the Amur upstream from the mouth of the Dondon. The two groups might thus be ancestral of the Ulch and Nanai people known to latter ethnologists; or, the "Ke tcheng" might in fact be Nivkhs.

- ^ La Pérouse, Jean François de Galaup, comte de (1831). de Lesseps, Jean Baptiste (ed.). Voyage de Lapérouse, rédigé d'après ses manuscrits, suivi d'un appendice renfermant tout ce que l'on a découvert depuis le naufrage, et enrichi de notes par m. de Lesseps. pp. 259–266.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Началось исследование Южного Сахалина под руководством лейтенанта Николая Васильевича Рудановского" [Study of South Sakhalin Started under Lieutenant Nikolay Vasilievich Rudanovsky] (in Russian). President Library of Russia. October 18, 1853. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

"I made my trips around Sakhalin Island in autumn and winter ...": reports of Lieutenant N. V. Rudanovskiy. 1853–1854

- ^

Burkhardt, Frederick; Secord, James A., eds. (2015). The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. Vol. 23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 9781316473184. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

The Russians had established a penal colony in northern Sakhalin in 1857 [...].

- ^ "Chekhov's trip to Sakhalin puts lockdown in perspective". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Mary and Susan, of Stonington, Aug. 10–31, 1848, Nicholson Whaling Collection; Charles W. Morgan, of New Bedford, Aug. 30–Sep. 5, 1902, G. W. Blunt White Library (GBWL).

- ^ Eliza Adams, of Fairhaven, Aug. 4–6, 1848, Old Dartmouth Historical Society; Erie, of Fairhaven, July 26 – Aug. 29, 1852, NWC; Sea Breeze, of New Bedford, July 8–10, 1874, GBWL.

- ^ William Wirt, of New Bedford, June 13, 1855, Nicholson Whaling Collection.

- ^ The Friend (Vol. IV, No. 9, September 29, 1855, pp. 68, 72, Honolulu)

- ^ Starbuck, Alexander (1878). History of the American Whale Fishery from Its Earliest Inception to the year 1876. Castle. ISBN 1-55521-537-8.

- ^ 16th Army, 2nd Far Eastern Front, Soviet Far East Command, 09.08,45[permanent dead link]

- ^ Forsyth, James (1994) [1992]. A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 354. ISBN 0-521-47771-9.

- ^ Ginsburgs, George (1983). The Citizenship Law of the USSR. Law in Eastern Europe No. 25. The Hague: Martinis Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 320–325. ISBN 90-247-2863-0.

- ^ Sandford, Daniel, "Sakhalin memories: Japanese stranded by war in the USSR", BBC, 3 August 2011.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan: Foreign Policy > Others > Japanese Territory > Northern Territories

- ^ Japan and Russia want to finally end World War II, agree it is 'abnormal' not to, CSMonitor.com. April 29, 2013.

- ^ Ivanov, Andrey (March 27, 2003). "18 The Far East". In Shahgedanova, Maria (ed.). The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia. Oxford Regional Environments. Vol. 3. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 428–429. ISBN 978-0-19-823384-8. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Ivlev, A. M. Soils of Sakhalin. New Delhi: Indian National Scientific Documentation Centre, 1974. Pages 9–28.

- ^ Тымь – an article in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. (In Russian, retrieved 21 June 2020.)

- ^ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской империи, 1897 г. (in Russian). Vol. LXXVII. 1904. pp. 34–37, 56–63.

- ^ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской империи, 1897 г. Vol. LXXVII. pp. 64–65.

- ^ Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской империи, 1897 г. Vol. LXXVII. pp. 36–37.

- ^ Winiarz, Adam (1994). "Książka polska w koloniach polskich na Dalekim Wschodzie (1897–1949)". Czasopismo Zakładu Narodowego im. Ossolińskich (in Polish). Vol. 5. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 66.

- ^ Сахалин становится островом близнецов? [Sakhalin is an island of twins?] (in Russian). Восток Медиа [Vostok Media]. February 13, 2009. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Carson, Cameron, "Karafuto 1945: An examination of the Japanese under Soviet rule and their subsequent expulsion" (2015). Honors Theses. Western Michigan University.

- ^ Sakhalin Hydrometeorological Service, accessed 19 April 2011

- ^ Penguin International Limited

- ^ Sakhalin Shipping Company Archived July 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sakhalin Railways". JSC Russian Railways. 2007. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Dickinson, Rob. "Steam and the Railways of Sakhalin Island". International Steam Page. Archived from the original on February 17, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Gauge conversion

- ^ Bolashenko, Serguei (Болашенко, С.) (July 6, 2006). Узкоколейная железная дорога Оха – Ноглики [Okha-Nogliki narrow-gauge railway]. САЙТ О ЖЕЛЕЗНОЙ ДОРОГЕ (in Russian). Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Moscow Times (July 7, 2008). "Railway a Gauge of Sakhalin's Future". The RZD-Partner. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Президент России хочет остров Сахалин соединить с материком [President of Russia wants to join Sakhalin Island to the mainland] (in Russian). PrimaMedia. November 19, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Minister Proposes 7km Bridge to Sakhalin Island". RIA Novosti. The Moscow Times. July 19, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ "Russia Threatens To Halt Sakhalin-2 Project Unless Shell Cleans Up". Terra Daily. Agence France-Presse. September 26, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (September 19, 2006). "Russia Halts Pipeline, Citing River Damage". The New York Times. p. C.11. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Cynical in Sakhalin". Financial Times. London. September 26, 2006. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- ^ "A deal is a deal". The Times. London. September 22, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "CEO delivers message at Sakhalin's first major energy conference" (Press release). Sakhalin Energy. September 27, 2006. Archived from the original on November 1, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2010. Citations for the date: "Sakhalin II: Laying the Base for Future Arctic Developments in Russia" (Press release). Sakhalin Energy. September 27, 2006. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010. "Media Archives 2006". Sakhalin Energy. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Russia aims to make Sakhalin island carbon neutral by 2025". Reuters. June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

Works cited[edit]

- Hudson, Mark J. (1999). Ruins of identity: ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824864194.

- Kim, Loretta E. (2019), Ethnic Chrysalis, Harvard University Asia Center

- Nakamura, Kazuyuki (2010). "Kita kara no mōko shūrai wo meguru shōmondai" 「北からの蒙古襲来」をめぐる諸問題 [Several questions around "the Mongol attack from the north"]. In Kikuchi, Toshihiko (ed.). Hokutō Ajia no rekishi to bunka 北東アジアの歴史と文化 [A history and cultures of Northeast Asia] (in Japanese). Hokkaido University Press. ISBN 9784832967342.

- Nakamura, Kazuyuki (2012). "Gen-Mindai no shiryō kara mieru Ainu to Ainu bunka" 元・明代の史料にみえるアイヌとアイヌ文化 [The Ainu and Ainu culture from historical records of the Yuan and Ming]. In Katō, Hirofumi; Suzuki, Kenji (eds.). Atarashii Ainu shi no kōchiku : senshi hen, kodai hen, chūsei hen 新しいアイヌ史の構築 : 先史編・古代編・中世編 (in Japanese). Hokkaido University. pp. 138–145.

- Nakayama, Taisho (2015), Japanese Society on Karafuto, Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese Border: Karafuto / Sakhalin, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-315-75268-6 – via Google Books

- Narangoa, Li (2014), Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590–2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231160704

- Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017), A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule, Stanford University Press, ISBN 9781503600683

- Smith, Norman, ed. (2017), Empire and Environment in the Making of Manchuria, University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 9780774832908

- Sasaki, Shiro (1999), Trading Brokers and Partners with China, Russia, and Japan, In W. W. Fitzhugh and C. O. Dubreuil (eds.) Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, Arctic Study Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

- Stephan, John (1971). Sakhalin: a history. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198215509.

- Tanaka, Sakurako (Sherry) (2000). The Ainu of Tsugaru : the indigenous history and shamanism of northern Japan (Thesis). The University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0076926.

- Trekhsviatskyi, Anatolii (2007). "At the far edge of the Chinese Oikoumene: Mutual relations of the indigenous population of Sakhalin with the Yuan and Ming dynasties". Journal of Asian History. 41 (2): 131–155. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41933457.

- Walker, Brett L. (2006). The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590–1800. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24834-1.

- Zgusta, Richard (2015). The peoples of Northeast Asia through time : precolonial ethnic and cultural processes along the coast between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004300439. OCLC 912504787.

Further reading[edit]

- Anton Chekhov, A Journey to Sakhalin (1895), including:

- Saghalien [or Sakhalin] Island (1891–1895)

- Across Siberia

- C. H. Hawes, In the Uttermost East (London, 1903). (quoted in EB1911, see below)

- Ajay Kamalakaran, Sakhalin Unplugged (Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, 2006)

- Ajay Kamalakaran, Globetrotting for Love and Other Stories from Sakhalin Island (Times Group Books, 2017)

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). p. 54.

- John J. Stephan, Sakhalin: A History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971.

External links[edit]

- Map of the Sakhalin Hydrocarbon Region – at Blackbourn Geoconsulting

- TransGlobal Highway – Proposed Sakhalin–Hokkaidō Friendship Tunnel

- Steam and the Railways of Sakhalin

- Maps of Ezo, Sakhalin and Kuril Islands from 1854