Substitution cipher

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encrypting in which units of plaintext are replaced with the ciphertext, in a defined manner, with the help of a key; the "units" may be single letters (the most common), pairs of letters, triplets of letters, mixtures of the above, and so forth. The receiver deciphers the text by performing the inverse substitution process to extract the original message.

Substitution ciphers can be compared with transposition ciphers. In a transposition cipher, the units of the plaintext are rearranged in a different and usually quite complex order, but the units themselves are left unchanged. By contrast, in a substitution cipher, the units of the plaintext are retained in the same sequence in the ciphertext, but the units themselves are altered.

There are a number of different types of substitution cipher. If the cipher operates on single letters, it is termed a simple substitution cipher; a cipher that operates on larger groups of letters is termed polygraphic. A monoalphabetic cipher uses fixed substitution over the entire message, whereas a polyalphabetic cipher uses a number of substitutions at different positions in the message, where a unit from the plaintext is mapped to one of several possibilities in the ciphertext and vice versa.

The first ever published description of how to crack simple substitution ciphers was given by Al-Kindi in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages written around 850 CE. The method he described is now known as frequency analysis.

Types[edit]

Simple[edit]

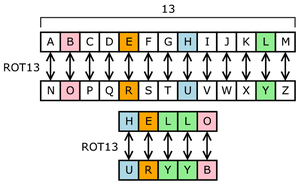

Substitution of single letters separately—simple substitution—can be demonstrated by writing out the alphabet in some order to represent the substitution. This is termed a substitution alphabet. The cipher alphabet may be shifted or reversed (creating the Caesar and Atbash ciphers, respectively) or scrambled in a more complex fashion, in which case it is called a mixed alphabet or deranged alphabet. Traditionally, mixed alphabets may be created by first writing out a keyword, removing repeated letters in it, then writing all the remaining letters in the alphabet in the usual order.

Using this system, the keyword "zebras" gives us the following alphabets:

| Plaintext alphabet | ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ |

|---|---|

| Ciphertext alphabet | ZEBRASCDFGHIJKLMNOPQTUVWXY |

A message

flee at once. we are discovered!

enciphers to

SIAA ZQ LKBA. VA ZOA RFPBLUAOAR!

Usually the ciphertext is written out in blocks of fixed length, omitting punctuation and spaces; this is done to disguise word boundaries from the plaintext and to help avoid transmission errors. These blocks are called "groups", and sometimes a "group count" (i.e. the number of groups) is given as an additional check. Five-letter groups are often used, dating from when messages used to be transmitted by telegraph:

SIAAZ QLKBA VAZOA RFPBL UAOAR

If the length of the message happens not to be divisible by five, it may be padded at the end with "nulls". These can be any characters that decrypt to obvious nonsense, so that the receiver can easily spot them and discard them.

The ciphertext alphabet is sometimes different from the plaintext alphabet; for example, in the pigpen cipher, the ciphertext consists of a set of symbols derived from a grid. For example:

Such features make little difference to the security of a scheme, however – at the very least, any set of strange symbols can be transcribed back into an A-Z alphabet and dealt with as normal.

In lists and catalogues for salespeople, a very simple encryption is sometimes used to replace numeric digits by letters.

| Plaintext digits | 1234567890 |

|---|---|

| Ciphertext alphabets | MAKEPROFIT [1] |

Example: MAT would be used to represent 120.

Security[edit]

Although the traditional keyword method for creating a mixed substitution alphabet is simple, a serious disadvantage is that the last letters of the alphabet (which are mostly low frequency) tend to stay at the end. A stronger way of constructing a mixed alphabet is to generate the substitution alphabet completely randomly.

Although the number of possible substitution alphabets is very large (26! ≈ 288.4, or about 88 bits), this cipher is not very strong, and is easily broken. Provided the message is of reasonable length (see below), the cryptanalyst can deduce the probable meaning of the most common symbols by analyzing the frequency distribution of the ciphertext. This allows formation of partial words, which can be tentatively filled in, progressively expanding the (partial) solution (see frequency analysis for a demonstration of this). In some cases, underlying words can also be determined from the pattern of their letters; for example, attract, osseous, and words with those two as the root are the only common English words with the pattern ABBCADB. Many people solve such ciphers for recreation, as with cryptogram puzzles in the newspaper.

According to the unicity distance of English, 27.6 letters of ciphertext are required to crack a mixed alphabet simple substitution. In practice, typically about 50 letters are needed, although some messages can be broken with fewer if unusual patterns are found. In other cases, the plaintext can be contrived to have a nearly flat frequency distribution, and much longer plaintexts will then be required by the cryptanalyst.

Nomenclator[edit]

One once-common variant of the substitution cipher is the nomenclator. Named after the public official who announced the titles of visiting dignitaries, this cipher uses a small code sheet containing letter, syllable and word substitution tables, sometimes homophonic, that typically converted symbols into numbers. Originally the code portion was restricted to the names of important people, hence the name of the cipher; in later years, it covered many common words and place names as well. The symbols for whole words (codewords in modern parlance) and letters (cipher in modern parlance) were not distinguished in the ciphertext. The Rossignols' Great Cipher used by Louis XIV of France was one.

Nomenclators were the standard fare of diplomatic correspondence, espionage, and advanced political conspiracy from the early fifteenth century to the late eighteenth century; most conspirators were and have remained less cryptographically sophisticated. Although government intelligence cryptanalysts were systematically breaking nomenclators by the mid-sixteenth century, and superior systems had been available since 1467, the usual response to cryptanalysis was simply to make the tables larger. By the late eighteenth century, when the system was beginning to die out, some nomenclators had 50,000 symbols.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, not all nomenclators were broken; today, cryptanalysis of archived ciphertexts remains a fruitful area of historical research.

Homophonic[edit]

An early attempt to increase the difficulty of frequency analysis attacks on substitution ciphers was to disguise plaintext letter frequencies by homophony. In these ciphers, plaintext letters map to more than one ciphertext symbol. Usually, the highest-frequency plaintext symbols are given more equivalents than lower frequency letters. In this way, the frequency distribution is flattened, making analysis more difficult.

Since more than 26 characters will be required in the ciphertext alphabet, various solutions are employed to invent larger alphabets. Perhaps the simplest is to use a numeric substitution 'alphabet'. Another method consists of simple variations on the existing alphabet; uppercase, lowercase, upside down, etc. More artistically, though not necessarily more securely, some homophonic ciphers employed wholly invented alphabets of fanciful symbols.

The book cipher is a type of homophonic cipher, one example being the Beale ciphers. This is a story of buried treasure that was described in 1819–21 by use of a ciphered text that was keyed to the Declaration of Independence. Here each ciphertext character was represented by a number. The number was determined by taking the plaintext character and finding a word in the Declaration of Independence that started with that character and using the numerical position of that word in the Declaration of Independence as the encrypted form of that letter. Since many words in the Declaration of Independence start with the same letter, the encryption of that character could be any of the numbers associated with the words in the Declaration of Independence that start with that letter. Deciphering the encrypted text character X (which is a number) is as simple as looking up the Xth word of the Declaration of Independence and using the first letter of that word as the decrypted character.

Another homophonic cipher was described by Stahl[2][3] and was one of the first[citation needed] attempts to provide for computer security of data systems in computers through encryption. Stahl constructed the cipher in such a way that the number of homophones for a given character was in proportion to the frequency of the character, thus making frequency analysis much more difficult.

Francesco I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, used the earliest known example of a homophonic substitution cipher in 1401 for correspondence with one Simone de Crema.[4][5]

Mary, Queen of Scots, while imprisoned by Elizabeth I, during the years from 1578 to 1584 used homophonic ciphers with additional encryption using a nomenclator for frequent prefixes, suffixes, and proper names while communicating with her allies including Michel de Castelnau.[6]

Polyalphabetic[edit]

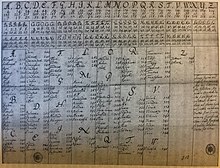

The work of Al-Qalqashandi (1355-1418), based on the earlier work of Ibn al-Durayhim (1312–1359), contained the first published discussion of the substitution and transposition of ciphers, as well as the first description of a polyalphabetic cipher, in which each plaintext letter is assigned more than one substitute.[7] Polyalphabetic substitution ciphers were later described in 1467 by Leone Battista Alberti in the form of disks. Johannes Trithemius, in his book Steganographia (Ancient Greek for "hidden writing") introduced the now more standard form of a tableau (see below; ca. 1500 but not published until much later). A more sophisticated version using mixed alphabets was described in 1563 by Giovanni Battista della Porta in his book, De Furtivis Literarum Notis (Latin for "On concealed characters in writing").

In a polyalphabetic cipher, multiple cipher alphabets are used. To facilitate encryption, all the alphabets are usually written out in a large table, traditionally called a tableau. The tableau is usually 26×26, so that 26 full ciphertext alphabets are available. The method of filling the tableau, and of choosing which alphabet to use next, defines the particular polyalphabetic cipher. All such ciphers are easier to break than once believed, as substitution alphabets are repeated for sufficiently large plaintexts.

One of the most popular was that of Blaise de Vigenère. First published in 1585, it was considered unbreakable until 1863, and indeed was commonly called le chiffre indéchiffrable (French for "indecipherable cipher").

In the Vigenère cipher, the first row of the tableau is filled out with a copy of the plaintext alphabet, and successive rows are simply shifted one place to the left. (Such a simple tableau is called a tabula recta, and mathematically corresponds to adding the plaintext and key letters, modulo 26.) A keyword is then used to choose which ciphertext alphabet to use. Each letter of the keyword is used in turn, and then they are repeated again from the beginning. So if the keyword is 'CAT', the first letter of plaintext is enciphered under alphabet 'C', the second under 'A', the third under 'T', the fourth under 'C' again, and so on. In practice, Vigenère keys were often phrases several words long.

In 1863, Friedrich Kasiski published a method (probably discovered secretly and independently before the Crimean War by Charles Babbage) which enabled the calculation of the length of the keyword in a Vigenère ciphered message. Once this was done, ciphertext letters that had been enciphered under the same alphabet could be picked out and attacked separately as a number of semi-independent simple substitutions - complicated by the fact that within one alphabet letters were separated and did not form complete words, but simplified by the fact that usually a tabula recta had been employed.

As such, even today a Vigenère type cipher should theoretically be difficult to break if mixed alphabets are used in the tableau, if the keyword is random, and if the total length of ciphertext is less than 27.67 times the length of the keyword.[8] These requirements are rarely understood in practice, and so Vigenère enciphered message security is usually less than might have been.

Other notable polyalphabetics include:

- The Gronsfeld cipher. This is identical to the Vigenère except that only 10 alphabets are used, and so the "keyword" is numerical.

- The Beaufort cipher. This is practically the same as the Vigenère, except the tabula recta is replaced by a backwards one, mathematically equivalent to ciphertext = key - plaintext. This operation is self-inverse, whereby the same table is used for both encryption and decryption.

- The autokey cipher, which mixes plaintext with a key to avoid periodicity.

- The running key cipher, where the key is made very long by using a passage from a book or similar text.

Modern stream ciphers can also be seen, from a sufficiently abstract perspective, to be a form of polyalphabetic cipher in which all the effort has gone into making the keystream as long and unpredictable as possible.

Polygraphic[edit]

In a polygraphic substitution cipher, plaintext letters are substituted in larger groups, instead of substituting letters individually. The first advantage is that the frequency distribution is much flatter than that of individual letters (though not actually flat in real languages; for example, 'TH' is much more common than 'XQ' in English). Second, the larger number of symbols requires correspondingly more ciphertext to productively analyze letter frequencies.

To substitute pairs of letters would take a substitution alphabet 676 symbols long (). In the same De Furtivis Literarum Notis mentioned above, della Porta actually proposed such a system, with a 20 x 20 tableau (for the 20 letters of the Italian/Latin alphabet he was using) filled with 400 unique glyphs. However the system was impractical and probably never actually used.

The earliest practical digraphic cipher (pairwise substitution), was the so-called Playfair cipher, invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1854. In this cipher, a 5 x 5 grid is filled with the letters of a mixed alphabet (two letters, usually I and J, are combined). A digraphic substitution is then simulated by taking pairs of letters as two corners of a rectangle, and using the other two corners as the ciphertext (see the Playfair cipher main article for a diagram). Special rules handle double letters and pairs falling in the same row or column. Playfair was in military use from the Boer War through World War II.

Several other practical polygraphics were introduced in 1901 by Felix Delastelle, including the bifid and four-square ciphers (both digraphic) and the trifid cipher (probably the first practical trigraphic).

The Hill cipher, invented in 1929 by Lester S. Hill, is a polygraphic substitution which can combine much larger groups of letters simultaneously using linear algebra. Each letter is treated as a digit in base 26: A = 0, B =1, and so on. (In a variation, 3 extra symbols are added to make the basis prime.) A block of n letters is then considered as a vector of n dimensions, and multiplied by a n x n matrix, modulo 26. The components of the matrix are the key, and should be random provided that the matrix is invertible in (to ensure decryption is possible). A mechanical version of the Hill cipher of dimension 6 was patented in 1929.[9]

The Hill cipher is vulnerable to a known-plaintext attack because it is completely linear, so it must be combined with some non-linear step to defeat this attack. The combination of wider and wider weak, linear diffusive steps like a Hill cipher, with non-linear substitution steps, ultimately leads to a substitution–permutation network (e.g. a Feistel cipher), so it is possible – from this extreme perspective – to consider modern block ciphers as a type of polygraphic substitution.

Mechanical[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

Between around World War I and the widespread availability of computers (for some governments this was approximately the 1950s or 1960s; for other organizations it was a decade or more later; for individuals it was no earlier than 1975), mechanical implementations of polyalphabetic substitution ciphers were widely used. Several inventors had similar ideas about the same time, and rotor cipher machines were patented four times in 1919. The most important of the resulting machines was the Enigma, especially in the versions used by the German military from approximately 1930. The Allies also developed and used rotor machines (e.g., SIGABA and Typex).

All of these were similar in that the substituted letter was chosen electrically from amongst the huge number of possible combinations resulting from the rotation of several letter disks. Since one or more of the disks rotated mechanically with each plaintext letter enciphered, the number of alphabets used was astronomical. Early versions of these machine were, nevertheless, breakable. William F. Friedman of the US Army's SIS early found vulnerabilities in Hebern's rotor machine, and GC&CS's Dillwyn Knox solved versions of the Enigma machine (those without the "plugboard") well before WWII began. Traffic protected by essentially all of the German military Enigmas was broken by Allied cryptanalysts, most notably those at Bletchley Park, beginning with the German Army variant used in the early 1930s. This version was broken by inspired mathematical insight by Marian Rejewski in Poland.

As far as is publicly known, no messages protected by the SIGABA and Typex machines were ever broken during or near the time when these systems were in service.

One-time pad[edit]

One type of substitution cipher, the one-time pad, is unique. It was invented near the end of World War I by Gilbert Vernam and Joseph Mauborgne in the US. It was mathematically proven unbreakable by Claude Shannon, probably during World War II; his work was first published in the late 1940s. In its most common implementation, the one-time pad can be called a substitution cipher only from an unusual perspective; typically, the plaintext letter is combined (not substituted) in some manner (e.g., XOR) with the key material character at that position.

The one-time pad is, in most cases, impractical as it requires that the key material be as long as the plaintext, actually random, used once and only once, and kept entirely secret from all except the sender and intended receiver. When these conditions are violated, even marginally, the one-time pad is no longer unbreakable. Soviet one-time pad messages sent from the US for a brief time during World War II used non-random key material. US cryptanalysts, beginning in the late 40s, were able to, entirely or partially, break a few thousand messages out of several hundred thousand. (See Venona project)

In a mechanical implementation, rather like the Rockex equipment, the one-time pad was used for messages sent on the Moscow-Washington hot line established after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In modern cryptography[edit]

Substitution ciphers as discussed above, especially the older pencil-and-paper hand ciphers, are no longer in serious use. However, the cryptographic concept of substitution carries on even today. From an abstract perspective, modern bit-oriented block ciphers (e.g., DES, or AES) can be viewed as substitution ciphers on a large binary alphabet. In addition, block ciphers often include smaller substitution tables called S-boxes. See also substitution–permutation network.

In popular culture[edit]

- Sherlock Holmes breaks a substitution cipher in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men". There, the cipher remained undeciphered for years if not decades; not due to its difficulty, but because no one suspected it to be a code, instead considering it childish scribblings.

- The Standard Galactic Alphabet, the writing system in the Commander Keen video games and in Minecraft.

- The Al Bhed language in Final Fantasy X is actually a substitution cipher, although it is pronounced phonetically (i.e. "you" in English is translated to "oui" in Al Bhed, but is pronounced the same way that "oui" is pronounced in French).

- The Minbari's alphabet from the Babylon 5 series is a substitution cipher from English.

- The language in Starfox Adventures: Dinosaur Planet spoken by native Saurians and Krystal is also a substitution cipher of the English alphabet.

- The television program Futurama contained a substitution cipher in which all 26 letters were replaced by symbols and called "Alien Language" Archived 2022-12-25 at the Wayback Machine. This was deciphered rather quickly by the die hard viewers by showing a "Slurm" ad with the word "Drink" in both plain English and the Alien language thus giving the key. Later, the producers created a second alien language that used a combination of replacement and mathematical Ciphers. Once the English letter of the alien language is deciphered, then the numerical value of that letter (0 for "A" through 25 for "Z" respectively) is then added (modulo 26) to the value of the previous letter showing the actual intended letter. These messages can be seen throughout every episode of the series and the subsequent movies.

- At the end of every season 1 episode of the cartoon series Gravity Falls, during the credit roll, there is one of three simple substitution ciphers: A -3 Caesar cipher (hinted by "3 letters back" at the end of the opening sequence), an Atbash cipher, or a letter-to-number simple substitution cipher. The season 1 finale encodes a message with all three. In the second season, Vigenère ciphers are used in place of the various monoalphabetic ciphers, each using a key hidden within its episode.

- In the Artemis Fowl series by Eoin Colfer there are three substitution ciphers; Gnommish, Centaurean and Eternean, which run along the bottom of the pages or are somewhere else within the books.

- In Bitterblue, the third novel by Kristin Cashore, substitution ciphers serve as an important form of coded communication.

- In the 2013 video game BioShock Infinite, there are substitution ciphers hidden throughout the game in which the player must find code books to help decipher them and gain access to a surplus of supplies.

- In the anime adaptation of The Devil Is a Part-Timer!, the language of Ente Isla, called Entean, uses a substitution cipher with the ciphertext alphabet AZYXEWVTISRLPNOMQKJHUGFDCB, leaving only A, E, I, O, U, L, N, and Q in their original positions.

See also[edit]

- Ban (unit) with Centiban Table

- Copiale cipher

- Dictionary coder – lossless data compression algorithms which operate by looking for matches between the text to be compressed and a set of strings (“dictionary”) maintained by the encoder; such a match is substituted by a reference to the string’s position in the set

- Leet

- Vigenère cipher

- Topics in cryptography

- Musical Substitution Ciphers

References[edit]

- ^ David Crawford / Mike Esterl, At Siemens, witnesses cite pattern of bribery, The Wall Street Journal, January 31, 2007: "Back at Munich headquarters, he [Michael Kutschenreuter, a former Siemens-Manager] told prosecutors, he learned of an encryption code he alleged was widely used at Siemens to itemize bribe payments. He said it was derived from the phrase "Make Profit," with the phrase's 10 letters corresponding to the numbers 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-0. Thus, with the letter A standing for 2 and P standing for 5, a reference to "file this in the APP file" meant a bribe was authorized at 2.55 percent of sales. - A spokesman for Siemens said it has no knowledge of a "Make Profit" encryption system."

- ^ Stahl, Fred A., On Computational Security, University of Illinois, 1974

- ^ Stahl, Fred A. "A homophonic cipher for computational cryptography Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine", afips, pp. 565, 1973 Proceedings of the National Computer Conference, 1973

- ^ David Salomon. Coding for Data and Computer Communications. Springer, 2005.

- ^ Fred A. Stahl. "A homophonic cipher for computational cryptography" Proceedings of the national computer conference and exposition (AFIPS '73), pp. 123–126, New York, USA, 1973.

- ^ Lasry, George; Biermann, Norbert; Tomokiyo, Satoshi (2023). "Deciphering Mary Stuart's lost letters from 1578-1584". Cryptologia. 47 (2): 101–202. doi:10.1080/01611194.2022.2160677. S2CID 256720092.

- ^ Lennon, Brian (2018). Passwords: Philology, Security, Authentication. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780674985377.

- ^ Toemeh, Ragheb (2014). "Certain investigations in Cryptanalysis of classical ciphers Using genetic algorithm". Shodhganga. hdl:10603/26543.

- ^ "Message Protector patent US1845947". February 14, 1929. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

External links[edit]

- Monoalphabetic Substitution Breaking A Monoalphabetic Encryption System Using a Known Plaintext Attack