Symphony No. 10 (Shostakovich)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93, by Dmitri Shostakovich was premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 17 December 1953. It is not clear when it was written. According to the composer, the symphony was composed between July and October 1953, but Tatiana Nikolayeva stated that it was completed in 1951. Sketches for some of the material date from 1946.[1]

Instrumentation[edit]

The symphony is scored for three flutes (first flute with B foot extension, second and third flutes doubling piccolo), three oboes (third doubling cor anglais), three clarinets (third doubling E-flat clarinet), three bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon), four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, tambourine, tam-tam, xylophone, and strings.[2]

Composition[edit]

The symphony has four movements and a duration of approximately 50-60 minutes:

- Moderato

- Allegro

- Allegretto – Largo –Più mosso

- Andante – Allegro – L'istesso tempo

I. Moderato[edit]

The first and longest movement is a slow movement in rough sonata form. As in his Fifth Symphony, Shostakovich quotes from one of his settings of Pushkin: in the first movement, from the second of his Op. 91: Four Monologues on Verses by Pushkin for bass and piano (1952), entitled "What is in My Name?". This theme of personal identity is picked up again in the third and fourth movements.[citation needed]

II. Allegro[edit]

The second movement is a short and loud scherzo with syncopated rhythms and semiquaver (sixteenth note) passages. The book Testimony said:

I did depict Stalin in my next symphony, the Tenth. I wrote it right after Stalin's death and no one has yet guessed what the symphony is about. It's about Stalin and the Stalin years. The second part, the scherzo, is a musical portrait of Stalin, roughly speaking. Of course, there are many other things in it, but that's the basis.[3]

Shostakovich biographer Laurel Fay wrote, "I have found no corroboration that such a specific program was either intended or perceived at the time of composition and first performance."[4] Musicologist Richard Taruskin called the proposition a "dubious revelation, which no one had previously suspected either in Russia or in the West".[5] Elizabeth Wilson adds: "The Tenth Symphony is often read as the composer’s commentary on the recent Stalinist era. But as so often in Shostakovich’s art, the exposition of external events is counter-opposed to the private world of his innermost feelings."[6]

III. Allegretto[edit]

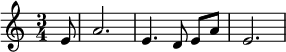

The third movement is a moderate dance-like suite of Mahlerian Nachtmusik – or nocturne, which is what Shostakovich called it.[citation needed] It is built around two musical codes: the DSCH theme representing Shostakovich, and the Elmira theme (ⓘ):

At concert pitch one fifth lower, the notes spell out "E La Mi Re A" in a combination of French and German notation. This motif, called out twelve times on the horn, represents Elmira Nazirova, a student of the composer with whom he fell in love. The motif is of ambiguous tonality, giving it an air of uncertainty or hollowness.[7]

In a letter to Nazirova, Shostakovich himself noted the similarity of the motif to the ape call in the first movement of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde, a work which he had been listening to around that time:[8] (ⓘ)

The same notes are used in both motifs, and both are repeatedly played by the horn. In the Chinese poem set by Mahler, the ape is a representation of death, while the Elmira motif itself occurs together with the "funeral knell" of a tam tam.[9] There is also more than a passing resemblance of this motif to the slow fanfare theme in the finale of Sibelius's Fifth Symphony; similar instrumentation (horns, woodwinds) is used for the Elmira motif here as in the Sibelius work.[citation needed] Over the course of the movement, the DSCH and Elmira themes alternate and gradually draw closer.

IV. Andante[edit]

In the fourth and final movement, a slow "Andante" introduction segues abruptly into an "Allegro" wherein the DSCH theme is employed again. The coda effects a transition to E Major and, at in the final measures, several instruments glissando from an E to the next E.

The DSCH-motif is anticipated throughout the first movement of the 10th Symphony: In the 7th bar of the start of the symphony the violins doubled by the violas play a D for 5 bars which is then directly followed by an E♭; 9 bars before rehearsal mark 29 the violins play the motif in an inverted order D-C-H-S (or D-C-B-E♭). The first time the motif is heard in its correct order in the whole symphony is in the 3rd movement, right after a short canon on the beginning melody starting from the 3rd beat of the 5th bar after rehearsal mark 104 (Fig. 11) where it is played in unison by the piccolo, the 1st flute and the 1st oboe (compassing a range of three octaves).[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ Wilson, Elizabeth (1994) p. 262. Shostakovich: A Life Remembered. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04465-1.

- ^ "Dmitri Shostakovich – Symphony No.10 in E minor". www.boosey.com. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Volkov, Solomon (2004). Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. Limelight Editions. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-87910-998-1. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Fay, Laurel E. (2000). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press. p. 327 note 14. ISBN 978-0-19-513438-4. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Taruskin, Richard (2 December 2008). On Russian Music. University of California Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-520-94280-6. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Elizabeth Wilson, p. 305

- ^ Nelly Kravetz, New Insight into the Tenth Symphony, p. 162. In Bartlett, R. (ed) Shostakovich in Context.

- ^ Kravetz p. 163.

- ^ Kravetz p. 162.

External links[edit]

- London Shostakovich Orchestra

- Shostakovich's Tenth Symphony: The Azerbaijani Link – Elmira Nazirova, by Aida Huseinova, Azerbaijan International Vol. 11:1 (Spring 2003), pp. 54–59.

- Melodic Signatures in Shostakovich's 10th Symphony, by Aida Huseinova, Azerbaijan International, Vol. 11:1 (Spring 2003), p. 57.

- Shostakovich's muse, by Noam Ben-Zeev, Ha'aretz, 2 April 2007

- Second movement played by Venezuela's Teresa Carreño Youth Orchestra