Uncanny valley

The uncanny valley (Japanese: 不気味の谷, Hepburn: bukimi no tani) effect is a hypothesized psychological and aesthetic relation between an object's degree of resemblance to a human being and the emotional response to the object. Examples of the phenomenon exist among robotics, 3D computer animations and lifelike dolls. The increasing prevalence of digital technologies (e.g., virtual reality, augmented reality, and photorealistic computer animation) has propagated discussions and citations of the "valley"; such conversation has enhanced the construct's verisimilitude. The uncanny valley hypothesis predicts that an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting eerie feelings in viewers.

Etymology[edit]

As related to robotics engineering, robotics professor Masahiro Mori first introduced the concept in 1970 from his book titled Bukimi No Tani (不気味の谷), phrasing it as bukimi no tani genshō (不気味の谷現象, lit. 'uncanny valley phenomenon').[1] Bukimi no tani was translated literally as uncanny valley in the 1978 book Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction written by Jasia Reichardt.[2] Over time, this translation created an unintended association of the concept to Ernst Jentsch's psychoanalytic concept of the uncanny established in his 1906 essay On the Psychology of the Uncanny (German: Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen),[3][4] which was then critiqued and extended in Sigmund Freud's 1919 essay The Uncanny (German: Das Unheimliche).[5]

Hypothesis[edit]

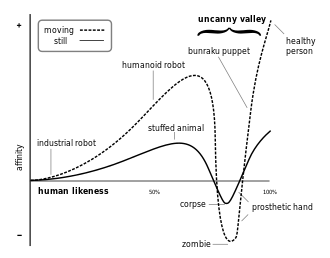

Mori's original hypothesis states that as the appearance of a robot is made more human, some observers' emotional response to the robot becomes increasingly positive and empathetic, until it becomes almost human, at which point the response quickly becomes strong revulsion. However, as the robot's appearance continues to become less distinguishable from that of a human being, the emotional response becomes positive once again and approaches human-to-human empathy levels.[7] When plotted on a graph, the reactions are indicated by a steep decrease followed by a steep increase (hence the "valley" part of the name) in the areas where anthropomorphism is closest to reality.

This interval of repulsive response aroused by a robot with appearance and motion between a "somewhat human" and "fully human" entity is the uncanny valley effect. The name represents the idea that an almost human-looking robot seems overly "strange" to some human beings, produces a feeling of uncanniness, and thus fails to evoke the empathic response required for productive human–robot interaction.[7]

Theoretical basis[edit]

A number of theories have been proposed to explain the cognitive mechanism causing the phenomenon:

- Mate selection: Automatic, stimulus-driven appraisals of uncanny stimuli elicit aversion by activating an evolved cognitive mechanism for the avoidance of selecting mates with low fertility, poor hormonal health, or ineffective immune systems based on visible features of the face and body that are predictive of those traits.[8]

- Mortality salience: Viewing an "uncanny" robot elicits an innate fear of death and culturally supported defenses for coping with death's inevitability.... [P]artially disassembled androids...play on subconscious fears of reduction, replacement, and annihilation: (1) A mechanism with a human façade and a mechanical interior plays on our subconscious fear that we are all just soulless machines. (2) Androids in various states of mutilation, decapitation, or disassembly are reminiscent of a battlefield after a conflict and, as such, serve as a reminder of our mortality. (3) Since most androids are copies of actual people, they are doppelgängers and may elicit a fear of being replaced, on the job, in a relationship, and so on. (4) The jerkiness of an android's movements could be unsettling because it elicits a fear of losing bodily control.[9]

- Pathogen avoidance: Uncanny stimuli may activate a cognitive mechanism that originally evolved to motivate the avoidance of potential sources of pathogens by eliciting a disgust response. "The more human an organism looks, the stronger the aversion to its defects, because (1) defects indicate disease, (2) more human-looking organisms are more closely related to human beings genetically, and (3) the probability of contracting disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and other parasites increases with genetic similarity."[8] The visual anomalies of androids, robots, and other animated human characters cause reactions of alarm and revulsion, similar to corpses and visibly diseased individuals.[10][11]

- Sorites paradoxes: Stimuli with human and nonhuman traits undermine our sense of human identity by linking qualitatively different categories, human and nonhuman, by a quantitative metric: degree of human likeness.[12]

- Violation of human norms: If an entity looks sufficiently nonhuman, its human characteristics are noticeable, generating empathy. However, if the entity looks almost human, it elicits our model of a human other and its detailed normative expectations. The nonhuman characteristics are noticeable, giving the human viewer a sense of strangeness. In other words, a robot which has an appearance in the uncanny valley range is not judged as a robot doing a passable job at pretending to be human, but instead as an abnormal human doing a bad job at seeming like a normal person. This has been associated with perceptual uncertainty and the theory of predictive coding.[13][14][15]

- Conflicting perceptual cues: The negative effect associated with uncanny stimuli is produced by the activation of conflicting cognitive representations. Perceptual tension occurs when an individual perceives conflicting cues to category membership, such as when a humanoid figure moves like a robot, or has other visible robot features. This cognitive conflict is experienced as psychological discomfort (i.e., "eeriness"), much like the discomfort that is experienced with cognitive dissonance.[16][17] Several studies support this possibility. Mathur and Reichling found that the time subjects took to gauge a robot face's human- or mechanical-resemblance peaked for faces deepest in the uncanny valley, suggesting that perceptually classifying these faces as "human" or "robot" posed a greater cognitive challenge.[18] However, they found that while perceptual confusion coincided with the uncanny valley, it did not mediate the effect of the uncanny valley on subjects' social and emotional reactions—suggesting that perceptual confusion may not be the mechanism behind the uncanny valley effect. Burleigh and colleagues demonstrated that faces at the midpoint between human and non-human stimuli produced a level of reported eeriness that diverged from an otherwise linear model relating human-likeness to affect.[19] Yamada et al. found that cognitive difficulty was associated with negative affect at the midpoint of a morphed continuum (e.g., a series of stimuli morphing between a cartoon dog and a real dog).[20] Ferrey et al. demonstrated that the midpoint between images on a continuum anchored by two stimulus categories produced a maximum of negative affect, and found this with both human and non-human entities.[16] Schoenherr and Burleigh provide examples from history and culture that evidence an aversion to hybrid entities, such as the aversion to genetically modified organisms ("Frankenfoods").[21] Finally, Moore developed a Bayesian mathematical model that provides a quantitative account of perceptual conflict.[22] There has been some debate as to the precise mechanisms that are responsible. It has been argued that the effect is driven by categorization difficulty,[19][20] configural processing, perceptual mismatch,[23] frequency-based sensitization,[24] and inhibitory devaluation.[16]

- Threat to humans' distinctiveness and identity: Negative reactions toward very humanlike robots can be related to the challenge that this kind of robot leads to the categorical human – non-human distinction. Kaplan[25] stated that these new machines challenge human uniqueness, pushing for a redefinition of humanness. Ferrari, Paladino and Jetten[26] found that the increase of anthropomorphic appearance of a robot leads to an enhancement of threat to the human distinctiveness and identity. The more a robot resembles a real person, the more it represents a challenge to our social identity as human beings.

- Religious definition of human identity: The existence of artificial but humanlike entities is viewed by some as a threat to the concept of human identity. An example can be found in the theoretical framework of psychiatrist Irvin Yalom. Yalom explains that humans construct psychological defenses to avoid existential anxiety stemming from death. One of these defenses is 'specialness', the irrational belief that aging and death as central premises of life apply to all others but oneself.[27] The experience of the very humanlike "living" robot can be so rich and compelling that it challenges humans' notions of "specialness" and existential defenses, eliciting existential anxiety. In folklore, the creation of human-like, but soulless, beings is often shown to be unwise, as with the golem in Judaism, whose absence of human empathy and spirit can lead to disaster, however good the intentions of its creator.[28]

- Uncanny valley of the mind or AI: Due to rapid advancements in the areas of artificial intelligence and affective computing, cognitive scientists have also suggested the possibility of an "uncanny valley of mind".[29][30] Accordingly, people might experience strong feelings of aversion if they encounter highly advanced, emotion-sensitive technology. Among the possible explanations for this phenomenon, both a perceived loss of human uniqueness and expectations of immediate physical harm are discussed by contemporary research.

Research[edit]

A series of studies experimentally investigated whether uncanny valley effects exist for static images of robot faces. Mathur MB & Reichling DB[18] used two complementary sets of stimuli spanning the range from very mechanical to very human-like: first, a sample of 80 objectively chosen robot face images from Internet searches, and second, a morphometrically and graphically controlled 6-face series set of faces. They asked subjects to explicitly rate the likability of each face. To measure trust toward each face, subjects completed an investment game to measure indirectly how much money they were willing to "wager" on a robot's trustworthiness. Both stimulus sets showed a robust uncanny valley effect on explicitly rated likability and a more context-dependent uncanny valley on implicitly rated trust. Their exploratory analysis of one proposed mechanism for the uncanny valley, perceptual confusion at a category boundary, found that category confusion occurs in the uncanny valley but does not mediate the effect on social and emotional responses.

One study conducted in 2009 examined the evolutionary mechanism behind the aversion associated with the uncanny valley. A group of five monkeys were shown three images: two different 3D monkey faces (realistic, unrealistic), and a real photo of a monkey's face. The monkeys' eye-gaze was used as a proxy for preference or aversion. Since the realistic 3D monkey face was looked at less than either the real photo, or the unrealistic 3D monkey face, this was interpreted as an indication that the monkey participants found the realistic 3D face aversive, or otherwise preferred the other two images. As one would expect with the uncanny valley, more realism can result in less positive reactions, and this study demonstrated that neither human-specific cognitive processes, nor human culture explain the uncanny valley. In other words, this aversive reaction to realism can be said to be evolutionary in origin.[31]

As of 2011[update], researchers at University of California, San Diego and California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology were measuring human brain activations related to the uncanny valley.[32][33] In one study using fMRI, a group of cognitive scientists and roboticists found the biggest differences in brain responses for uncanny robots in parietal cortex, on both sides of the brain, specifically in the areas that connect the part of the brain's visual cortex that processes bodily movements with the section of the motor cortex thought to contain mirror neurons. The researchers say they saw, in essence, evidence of mismatch or perceptual conflict.[13] The brain "lit up" when the human-like appearance of the android and its robotic motion "didn't compute". Ayşe Pınar Saygın, an assistant professor from UCSD, stated that "The brain doesn't seem selectively tuned to either biological appearance or biological motion per se. What it seems to be doing is looking for its expectations to be met – for appearance and motion to be congruent."[15][34][35]

Viewer perception of facial expression and speech and the uncanny valley in realistic, human-like characters intended for video games and movies is being investigated by Tinwell et al., 2011.[36] Consideration is also given by Tinwell et al. (2010) as to how the uncanny may be exaggerated for antipathetic characters in survival horror games.[37] Building on the body of work already performed for android science, this research intends to build a conceptual mapping of the uncanny valley using 3D characters generated in a real-time gaming engine. The goal is to analyze how cross-modal factors of facial expression and speech can exaggerate the uncanny. Tinwell et al., 2011[38] have also introduced the notion of an 'unscalable' uncanny wall that suggests that a viewer's discernment for detecting imperfections in realism will keep pace with new technologies in simulating realism. A summary of Angela Tinwell's research on the uncanny valley, psychological reasons behind the uncanny valley and how designers may overcome the uncanny in human-like virtual characters is provided in her book, The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation by CRC Press.

Studies in 2015 and 2018 observed that autistic individuals were less affected by the uncanny valley,[39] and autistic children even not at all.[40] The suspected causes were their reduced sensibility for subtle facial changes and limited visual experiences due to diminished social motivation.[40] In return, the social ostracism of autistics may be caused by the uncanny valley effect in the neurotypical society.[41] The effort of autistic individuals to appear neurotypical may thereby be misinterpreted as neurotypical people behaving atypically "creepy".[41] Outing or improved masking may help autistic individuals in such cases.[41]

Design principles[edit]

A number of design principles have been proposed for avoiding the uncanny valley:

- Design elements should match in human realism. A robot may look uncanny when human and nonhuman elements are mixed. For example, both a robot with a synthetic voice or a human being with a human voice have been found to be less eerie than a robot with a human voice or a human being with a synthetic voice.[42] For a robot to give a more positive impression, its degree of human realism in appearance should also match its degree of human realism in behavior.[43] If an animated character looks more human than its movement, this gives a negative impression.[44] Human neuroimaging studies also indicate matching appearance and motion kinematics are important.[13][45][46]

- Reducing conflict and uncertainty by matching appearance, behavior, and ability. In terms of performance, if a robot looks too appliance-like, people expect little from it; if it looks too human, people expect too much from it.[43] A highly human-like appearance leads to an expectation that certain behaviors are present, such as humanlike motion dynamics. This likely operates at a sub-conscious level and may have a biological basis. Neuroscientists have noted "when the brain's expectations are not met, the brain...generates a 'prediction error'. As human-like artificial agents become more commonplace, perhaps our perceptual systems will be re-tuned to accommodate these new social partners. Or perhaps, we will decide 'it is not a good idea to make [robots] so clearly in our image after all'."[13][46][47]

- Human facial proportions and photorealistic texture should only be used together. A photorealistic human texture demands human facial proportions, or the computer generated character can result in the uncanny valley. Abnormal facial proportions, including those typically used by artists to enhance attractiveness (e.g., larger eyes), can look eerie with a photorealistic human texture.

Criticism[edit]

A number of criticisms have been raised concerning whether the uncanny valley exists as a unified phenomenon amenable to scientific scrutiny:

- The uncanny valley effect is a heterogeneous group of phenomena. Phenomena considered as exhibiting the uncanny valley effect can be diverse, involve different sense modalities, and have multiple, possibly overlapping causes. People's cultural heritage may have a considerable influence on how androids are perceived with respect to the uncanny valley.[48]

- The uncanny valley effect may be generational. Younger generations, more used to computer-generated imagery (CGI), robots, and such, may be less likely to be affected by this hypothesized issue.[49]

- The uncanny valley effect is simply a specific case of information processing such as categorization and frequency-based effects. In contrast to the assumption that the uncanny valley is based on a heterogeneous group of phenomena, recent arguments have suggested that uncanny valley-like phenomena simply represent the products of information processing such as categorization. Cheetham et al.[50] have argued that the uncanny valley effect can be understood in terms of categorization processes, with a category boundary defining 'the valley'. Extending this argument, Burleigh and Schoenherr[51] suggested that the effects associated with the uncanny valley can be divided into those attributable to the category boundary and individual exemplar frequency. Namely, the negative affective responses attributed to the uncanny valley were simply a result of the frequency of exposure, similar to the mere-exposure effect. By varying the frequency of training items, they were able to demonstrate a dissociation between cognitive uncertainty based on the category boundary and affective uncertainty based on the frequency of training exemplars. In a follow-up study, Schoenherr and Burleigh[52] demonstrated that an instructional manipulation affected categorization accuracy but not ratings of negative affect. Thus, generational effects and cultural artifacts can be accounted for with basic information processing mechanisms.[21] These and related findings have been used to argue that the uncanny valley is merely an artifact of having greater familiarity with members of human categories and does not reflect a unique phenomenon.

- The uncanny valley effect occurs at any degree of human likeness. Hanson has also stated that uncanny entities may appear anywhere in a spectrum ranging from the abstract (e.g., MIT's robot Lazlo) to the perfectly human (e.g., cosmetically atypical people).[53] Capgras delusion is a relatively rare condition in which the patient believes that people (or, in some cases, things) have been replaced with duplicates. These duplicates are accepted rationally as identical in physical properties, but the irrational belief is held that the "true" entity has been replaced with something else. Some people with Capgras delusion claim that the duplicate is a robot. Ellis and Lewis argue that the delusion arises from an intact system for overt recognition coupled with a damaged system for covert recognition, which results in conflict over an individual being identifiable but not familiar in any emotional sense.[54] This supports the opinion that the uncanny valley effect could occur due to issues of categorical perception that are particular to how the brain processes information.[46][55]

- Good design can avoid the uncanny valley effect. David Hanson has criticized Mori's hypothesis that entities having an almost human appearance will necessarily be evaluated negatively.[53] He has shown that the uncanny valley effect could be eliminated by adding neotenous, cartoonish features to entities that had formerly caused an uncanny valley effect.[53] This method incorporates the idea that humans find characteristics appealing when they are reminiscent of the young of our own (as well as many other) species, as used in cartoons.

Similar effects[edit]

If the uncanny valley effect is the result of general cognitive processes, there should be evidence in evolutionary history and cultural artifacts.[21] An effect similar to the uncanny valley was noted by Charles Darwin in 1839:

The expression of this [Trigonocephalus] snake's face was hideous and fierce; the pupil consisted of a vertical slit in a mottled and coppery iris; the jaws were broad at the base, and the nose terminated in a triangular projection. I do not think I ever saw anything more ugly, excepting, perhaps, some of the vampire bats. I imagine this repulsive aspect originates from the features being placed in positions, with respect to each other, somewhat proportional to the human face; and thus we obtain a scale of hideousness.

— Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle[56]

A similar "uncanny valley" effect could, according to the ethical-futurist writer Jamais Cascio, show up when humans begin modifying themselves with transhuman enhancements (cf. body modification), which aim to improve the abilities of the human body beyond what would normally be possible, be it eyesight, muscle strength, or cognition.[57] So long as these enhancements remain within a perceived norm of human behavior, a negative reaction is unlikely, but once individuals supplant normal human variety, revulsion can be expected. However, according to this theory, once such technologies gain further distance from human norms, "transhuman" individuals would cease to be judged on human levels and instead be regarded as separate entities altogether (this point is what has been dubbed "posthuman"), and it is here that acceptance would rise once again out of the uncanny valley.[57] Another example comes from "pageant retouching" photos, especially of children, which some find disturbingly doll-like.[58]

In visual effects[edit]

A number of movies that use computer-generated imagery to show characters have been described by reviewers as giving a feeling of revulsion or "creepiness" as a result of the characters looking too realistic. Examples include the following:

- According to roboticist Dario Floreano, the baby character Billy in Pixar's groundbreaking 1988 animated short movie Tin Toy provoked negative audience reactions, which first caused the movie industry to consider the concept of the uncanny valley seriously.[59][60]

- The 2001 movie Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, one of the first photorealistic computer-animated feature movies, provoked negative reactions from some viewers due to its near-realistic yet imperfect visual depictions of human characters.[61][62][63] The Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw stated that while the movie's animation is brilliant, the "solemnly realist human faces look shriekingly phoney precisely because they're almost there but not quite".[64] Rolling Stone critic Peter Travers wrote of the movie, "At first it's fun to watch the characters, [...] But then you notice a coldness in the eyes, a mechanical quality in the movements".[65]

- Several reviewers of the 2004 animated movie The Polar Express termed its animation eerie. CNN.com reviewer Paul Clinton wrote, "Those human characters in the film come across as downright... well, creepy. So The Polar Express is at best disconcerting, and at worst, a wee bit horrifying".[66] The term "eerie" was used by reviewers Kurt Loder[67] and Manohla Dargis,[68] among others. Newsday reviewer John Anderson called the movie's characters "creepy" and "dead-eyed", and wrote that "The Polar Express is a zombie train".[69] Animation director Ward Jenkins wrote an online analysis describing how changes to the Polar Express characters' appearance, especially to their eyes and eyebrows, could have avoided what he considered a feeling of deadness in their faces.[70]

- In a review of the 2007 animated movie Beowulf, New York Times technology writer David Gallagher wrote that the movie failed the uncanny valley test, stating that the movie's villain, the monster Grendel, was "only slightly scarier" than the "closeups of our hero Beowulf's face... allowing viewers to admire every hair in his 3-D digital stubble".[71]

- Some reviewers of the 2009 animated film A Christmas Carol criticized its animation as creepy. Joe Neumaier of the New York Daily News said of the movie, "The motion-capture does no favors to co-stars [Gary] Oldman, Colin Firth and Robin Wright Penn, since, as in 'Polar Express,' the animated eyes never seem to focus. And for all the photorealism, when characters get wiggly-limbed and bouncy as in standard Disney cartoons, it's off-putting".[72] Mary Elizabeth Williams of Salon.com wrote of the film, "In the center of the action is Jim Carrey -- or at least a dead-eyed, doll-like version of Carrey".[73]

- The 2011 animated movie Mars Needs Moms was widely criticized for being creepy and unnatural because of its style of animation. The movie was among the biggest box office bombs in history, which may have been due in part to audience revulsion.[74][75][76][77] (Mars Needs Moms was produced by Robert Zemeckis's production company, ImageMovers, which had previously produced The Polar Express, Beowulf, and A Christmas Carol.)

- Reviewers had mixed opinions regarding whether the 2011 animated movie The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn was affected by the uncanny valley effect. Daniel D. Snyder of The Atlantic wrote, "Instead of trying to bring to life Herge's beautiful artwork, Spielberg and co. have opted to bring the movie into the 3D era using trendy motion-capture technique to recreate Tintin and his friends. Tintin's original face, while barebones, never suffered for a lack of expression. It's now outfitted with an alien and unfamiliar visage, his plastic skin dotted with pores and subtle wrinkles." He added, "In bringing them to life, Spielberg has made the characters dead.".[78] N.B. of The Economist termed elements of the animation "grotesque", writing, "Tintin, Captain Haddock and the others exist in settings that are almost photo-realistic, and nearly all of their features are those of flesh-and-blood people. And yet they still have the sausage fingers and distended noses of comic-strip characters. It's not so much 'The Secret of the Unicorn' as 'The Invasion of the Body Snatchers'".[79] However, other reviewers felt that the movie avoided the uncanny valley effect despite its animated characters' realism. Critic Dana Stevens of Slate wrote, "With the possible exception of the title character, the animated cast of Tintin narrowly escapes entrapment in the so-called 'uncanny valley'".[80] Wired magazine editor Kevin Kelly wrote of the movie, "we have passed beyond the uncanny valley into the plains of hyperreality".[81]

- In 2014, the titular protagonist of the movie Bob the Builder got a redesign which was described by some as "creepy".[82]

- In the French movie Animal Kingdom: Let's Go Ape it uses motion capture, the apes were criticized for looking creepy. As this review points out, they have "weirdly humanoid figures" and "recognisably human faces".[83]

- The 2019 film The Lion King, a remake of the 1994 film that featured photo-realistic digital animals instead of the earlier movie's more traditional animation, divided critics about the effectiveness of its imagery. Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post wrote that the images were so realistic that "2019 might best be remembered as the summer we left the Uncanny Valley for good".[84] However, other critics felt that the realism of the animals and setting rendered the scenes where the characters sing and dance disturbing and "weird".[85][86]

- The 2020 movie Sonic the Hedgehog was delayed for three months to make the title character's appearance less human-like and more cartoonish, after an extremely negative audience reaction to the movie's first trailer.[87]

- Multiple commentators cited the CGI half-human half-cat characters in the 2019 movie Cats as an example of the uncanny valley effect, first after the release of the trailer for the movie[88][89][90] and then after the movie's actual release.[91]

- In the 2022 Disney animated movie Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers, the uncanny valley is mentioned when the animated duo visits a place where several realistic CGI characters, including a Cats cameo from the 2019 movie, are inhabitants.[92]

- In the 2022 Disney+ series She-Hulk: Attorney at Law, the appearance of the main character, She-Hulk, who is depicted via CGI, was criticized by some reviewers as suffering from the uncanny valley effect, and negatively compared to the appearance of the Hulk in the same series.[93][94][95]

Virtual actors[edit]

An increasingly common practice is to feature virtual actors in movies: CGI likenesses of real actors used because the original actor either looks too old for the part or is deceased. Sometimes a virtual actor is created with involvement from the original actor (who may contribute motion capture, audio, etc.), while at other times the actor has no involvement. Reviewers have often criticized the use of virtual actors for its uncanny valley effect, saying it adds an eerie feeling to the movie. Examples of virtual actors that have received such criticism include replicas of Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator Salvation (2009)[96][97] and Terminator Genisys (2015),[98] Jeff Bridges in Tron: Legacy (2010),[99][100][101] Peter Cushing and Carrie Fisher in Rogue One (2016),[102][103] and Will Smith in Gemini Man (2019).[104]

The use of virtual actors is in contrast with digital de-aging, which can involve simply removing wrinkles from actors' faces. This practice has generally not been criticised for uncanny valley effects. One exception is the 2019 movie The Irishman, in which Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci were all de-aged to try to make them look as much as 50 years younger: one reviewer wrote that the actors' "hunched and stiff" body language stood in marked contrast to their facial appearance,[105] while another wrote that when De Niro's character was in his 30s of age, he looked like he was 50.[106]

Deepfake software, which first began to be widely used during 2017, uses machine learning to graft one person's facial expressions onto another's appearance, thus providing an alternate approach to both creating virtual actors and digital de-aging. Various individuals have created web videos that use deepfake software to re-create some of the notable previous uses of virtual actors and de-aging in movies.[106][107][108] Journalists have tended to praise these deepfake imitations, calling them "more naturalistic"[107] and "objectively better"[106] than the originals.

See also[edit]

- Android science

- Anthropocentrism

- Creepiness

- Cross-race effect

- Doll

- Frankenstein complex

- Minimal counterintuitiveness effect, things that are a little dissimilar to expectation are maximally memorable.

- Reborn doll

- Virtual human

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Mori, M. (2012). "The uncanny valley". IEEE Robotics and Automation. 19 (2). Translated by MacDorman, K. F.; Kageki, Norri. New York City: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: 98–100. doi:10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811.

- ^ Kageki, Norri (12 June 2012). "An Uncanny Mind: Masahiro Mori on the Uncanny Valley and Beyond". IEEE Spectrum. New York City: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Jentsch, Ernst (25 August 1906). "Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen" (PDF). Psychiatrisch-Neurologische Wochenschrift (in German). 8 (22): 195–198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ Misselhorn, Catrin (8 July 2009). "Empathy with inanimate objects and the uncanny valley". Minds and Machines. 19 (3). Heidelberg, Germnany: Springer: 345–359. doi:10.1007/s11023-009-9158-2. S2CID 2494335.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (2003). The Uncanny. Translated by McLintock, D. New York City: Penguin Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 9780142437476.

- ^ Tinwell, Angela (4 December 2014). The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation. CRC Press. pp. 165–. ISBN 9781466586956. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b Mori, M (2012) [1970]. "The uncanny valley". IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine. 19 (2): 98–100. doi:10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Rhodes, G. & Zebrowitz, L. A. (eds) (2002). Facial Attractiveness: Evolutionary, Cognitive, and Social Perspectives, Ablex Publishing.

- ^ MacDorman, K.F. (2005). "Mortality salience and the uncanny valley". 5th IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, 2005. IEEE. pp. 399–405. doi:10.1109/ICHR.2005.1573600. ISBN 978-0-7803-9320-2. S2CID 18596578. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Roberts, S. Craig (2012). Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 9780199586073.

- ^ Moosa, Mahdi Muhammad; Ud-Dean, S. M. Minhaz (March 2010). "Danger Avoidance: An Evolutionary Explanation of Uncanny Valley". Biological Theory. 5 (1): 12–14. doi:10.1162/BIOT_a_00016. ISSN 1555-5542. S2CID 83672322.

- ^ Ramey, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Saygin, A.P. (2011). "The Thing That Should Not Be: Predictive Coding and the Uncanny Valley in Perceiving Human and Humanoid Robot Actions". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 7 (4): 413–22. doi:10.1093/scan/nsr025. PMC 3324571. PMID 21515639.

- ^ Ho, C.; MacDorman, K. F. (2010). "Revisiting the uncanny valley theory: Developing and validating an alternative to the Godspeed indices". Computers in Human Behavior. 26 (6): 1508–1518. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.015. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b Kiderra, Inga (14 July 2011). "Your Brain on Androids". UCSD News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Ferrey, A. E.; Burleigh, T. J.; Fenske, M. J. (2015). "Stimulus-category competition, inhibition, and affective devaluation: a novel account of the uncanny valley". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 249. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00249. PMC 4358369. PMID 25821439.

- ^ Elliot, A. J.; Devine, P. G. (1994). "On the motivational nature of cognitive dissonance: Dissonance as psychological discomfort". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (3): 382–394. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.382.

- ^ a b c Mathur, Maya B.; Reichling, David B. (2016). "Navigating a social world with robot partners: a quantitative cartography of the Uncanny Valley". Cognition. 146: 22–32. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2015.09.008. PMID 26402646.

- ^ a b Burleigh, T. J.; Schoenherr, J. R.; Lacroix, G. L. (2013). "Does the uncanny valley exist? An empirical test of the relationship between eeriness and the human likeness of digitally created faces" (PDF). Computers in Human Behavior. 29 (3): 3. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b Yamada, Y.; Kawabe, T.; Ihaya, K. (2013). "Categorization difficulty is associated with negative evaluation in the 'uncanny valley' phenomenon". Japanese Psychological Research. 55 (1): 20–32. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5884.2012.00538.x. hdl:2324/21781.

- ^ a b c Schoenherr, J. R.; Burleigh, T. J. (2014). "Uncanny sociocultural categories". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1456. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01456. PMC 4300910. PMID 25653622.

- ^ Moore, R. K. (2012). "A Bayesian explanation of the 'Uncanny Valley' effect and related psychological phenomena". Scientific Reports. 2: 555. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2E.864M. doi:10.1038/srep00864. PMC 3499759. PMID 23162690.

- ^ Kätsyri, J.; Förger, K.; Mäkäräinen, M.; Takala, T. (2015). "A review of empirical evidence on different uncanny valley hypotheses: support for perceptual mismatch as one road to the valley of eeriness". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 390. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00390. PMC 4392592. PMID 25914661.

- ^ Burleigh, T. J.; Schoenherr, J. R. (2015). "A reappraisal of the uncanny valley: categorical perception or frequency-based sensitization?". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1488. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01488. PMC 4300869. PMID 25653623.

- ^ Kaplan, F. (2004). "Who is afraid of the humanoid? Investigating cultural differences in the acceptance of robots". International Journal of Humanoid Robotics. 1 (3): 465–480. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.78.5490. doi:10.1142/s0219843604000289.

- ^ Ferrari, F.; Paladino, M.P.; Jetten, J. (2016). "Blurring Human–Machine Distinctions: Anthropomorphic Appearance in Social Robots as a Threat to Human Distinctiveness". International Journal of Social Robotics. 8 (2): 287–302. doi:10.1007/s12369-016-0338-y. hdl:11572/143600. S2CID 28661659.

- ^ Yalom, Irvin D. (1980) "Existential Psychotherapy", Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, New York

- ^ Cathy S. Gelbin (2011). "Introduction to The Golem Returns" (PDF). University of Michigan Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Gray, Kurt; Wegner, Daniel M. (1 October 2012). "Feeling robots and human zombies: Mind perception and the uncanny valley". Cognition. 125 (1): 125–130. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.007. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 22784682. S2CID 7828975.

- ^ Stein, Jan-Philipp; Ohler, Peter (1 March 2017). "Venturing into the uncanny valley of mind—The influence of mind attribution on the acceptance of human-like characters in a virtual reality setting". Cognition. 160: 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2016.12.010. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 28043026. S2CID 2944145.

- ^ Kitta MacPherson (13 October 2009). "Monkey visual behavior falls into the uncanny valley". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (43). Princeton University: 18362–18366. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10618362S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910063106. PMC 2760490. PMID 19822765. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Brown, Mark (19 July 2011). "Science Exploring the uncanny valley of how brains react to humanoids". Wired. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Ramsey, Doug (13 May 2010). "Nineteen Projects Awarded Inaugural Calit2 Strategic Research Opportunities Grants". San Diego, California: University of California San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Robbins, Gary (4 August 2011). "UCSD exploring why robots creep people out". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Palmer, Chris (2 July 2011). "Exploring 'The thing that should not be'". Calit2. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Tinwell, A.; et al. (2011). "Facial expression of emotion and perception of the Uncanny Valley in virtual characters". Computers in Human Behavior. 27 (2): 741–749. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.018. S2CID 10258778. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Tinwell, A.; et al. (2010). "Uncanny Behaviour in Survival Horror Games". Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds. 2: 3–25. doi:10.1386/jgvw.2.1.3_1. S2CID 54682909. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Tinwell, A.; et al. (2011). "The Uncanny Wall". International Journal of Arts and Technology. 4 (3): 326. doi:10.1504/IJART.2011.041485. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ Jaramillo, Isabella (2015). Do Autistic Individuals Experience the Uncanny Valley Phenomenon?: The Role of Theory of Mind in Human-Robot (Honors thesis). HIM 1990-2015. 619. University of Central Florida. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ a b Feng, Shuyuan; et al. (1 November 2018). "The uncanny valley effect in typically developing children and its absence in children with autism spectrum disorders". PLOS ONE. 13 (11): e0206343. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306343F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206343. PMC 6211702. PMID 30383848.

- ^ a b c David Krauss (29 November 2022). "The "Uncanny Valley" Is a Lonely Place: Understanding the "uncanny valley" effect can help people living with autism". psychologytoday.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Mitchell et al., 2011.

- ^ a b Goetz, Kiesler, & Powers, 2003.

- ^ Vinayagamoorthy, Steed, & Slater, 2005.

- ^ Saygin et al., 2010.

- ^ a b c Saygin et al., 2011.

- ^ Gaylord, Chris (14 September 2011). "Uncanny Valley: Will we ever learn to live with artificial humans?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Bartneck Kanda, Ishiguro, & Hagita, 2007.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (3 September 2013). "Is the 'uncanny valley' a myth?". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Cheetham, Marcus; Suter, Pascal; Jäncke, Lutz (24 November 2011). "The human likeness dimension of the 'uncanny valley hypothesis': behavioral and functional MRI findings". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 5. London, England: Clarivate Analytics: 126. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00126. PMC 3223398. PMID 22131970.

- ^ Burleigh, T. J.; Schoenherr, J. R. (2014). "A reappraisal of the uncanny valley: categorical perception or frequency-based sensitization?". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1488. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01488. PMC 4300869. PMID 25653623.

- ^ Schoenherr, J. R.; Burleigh, T. J. (2020). "Dissociating affective and cognitive dimensions of uncertainty by altering regulatory focus". Acta Psychologica. 205: 103017. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2020.103017. PMID 32229317. S2CID 214749038.

- ^ a b c Hanson, David; Olney, Andrew; Pereira, Ismar A.; Zielke, Marge (2005). "Upending the Uncanny Valley". Proceedings of the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 20: 1728–1729.

- ^ Ellis, H.; Lewis, M. (2001). "Capgras delusion: A window on face recognition". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 5 (4): 149–156. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01620-x. PMID 11287268. S2CID 14058637.

- ^ Pollick, Frank E. (2009). "In Search of the Uncanny Valley. Analog communication: Evolution, brain mechanisms, dynamics, simulation" (PDF). The Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Charles Darwin. The Voyage of the Beagle . New York: Modern Library. 2001. p. 87.

- ^ a b Cascio, Jamais (27 October 2007). "The Second Uncanny Valley". Open the Future (blog). Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Erinhurt (26 February 2008). "Retouching memories?". University of Texas. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Dario Floreano. "Bio-Mimetic Robotics".[permanent dead link]

- ^ EPFL. http://moodle.epfl.ch/mod/resource/view.php?inpopup=true&id=41121[permanent dead link]

- ^ Eveleth, Rose (2 September 2013). "BBC – Future – Robots: Is the uncanny valley real?". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ Wissler, Virginia (2013). Illuminated Pixels: The Why, What, and How of Digital Lighting. Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4354-5635-8. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Plantec, Peter (19 December 2007). "Crossing the Great Uncanny Valley". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (2 August 2001). "Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within – Film – The Guardian". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Travers, Peter (6 July 2001). "Final Fantasy – Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Polar Express a creepy ride". CNN. 10 November 2004. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (10 November 2004). "'The Polar Express' Is All Too Human". MTV. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (10 November 2004). "Do You Hear Sleigh Bells? Nah, Just Tom Hanks and Some Train". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Anderson, John (10 November 2004). "'Polar Express' derails in zombie land". Newsday. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Jenkins, Ward (18 December 2004). "The Polar Express: A Virtual Train Wreck (conclusion)". The Ward-O-Matic Blog. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Gallagher, David F. (15 November 2007). "Digital Actors in 'Beowulf' Are Just Uncanny". The New York Times Bits Blog. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Neumaier, Joe (5 November 2009). "Blah, humbug! 'A Christmas Carol's 3-D spin on Dickens well done in parts but lacks spirit". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Williams, Mary Elizabeth (5 November 2009). "Disney's 'A Christmas Carol': Bah, humbug!". Salon. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Kim, Jonathan (28 March 2011). "Mars Needs Moms and the Uncanny Valley". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Nakashima, Ryan (4 April 2011). "Too real means too creepy in new Disney animation". USA Today. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (14 March 2011). "Many Culprits in Fall of a Family Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Pavlus, John (31 March 2011). "Did The 'Uncanny Valley' Kill Disney's CGI Company?". Fastcodesign.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Snyder, Daniel D. (26 December 2011). "'Tintin' and the Curious Case of the Dead Eyes". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ N.B. (31 October 2011). "Tintin and the dead-eyed zombies". The Economist. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Dana (21 December 2011). "Tintin, So So". Slate. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Kelly, Kevin. "Beyond the Uncanny Valley". The Technium. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ John McCarthy (13 October 2014), Bob the Builder: Can Mattel rebuild him? Twitter doesn't think so, The Drum, archived from the original on 7 December 2023, retrieved 6 December 2023

- ^ "Animal Kingdom: Let's Go Ape". Time Out Worldwide. 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (18 July 2019). "'The Lion King' leads us out of Uncanny Valley and into Disney's branded new world". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Harvilla, Rob (19 July 2019). "The 'Lion King' Remake Exists. But Why?". The Ringer. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Hyper-Real or Hyper-Weird? 'The Lion King's' Uncanny Valley Problem". HuffPost. 16 July 2019. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (24 May 2019). "Sonic movie delayed to February 2020 so they can fix Sonic". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "'Cats' trailer plunges into the uncanny valley of digital fur". Engadget. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (19 July 2019). "Litter-ally terrifying: is Cats the creepiest film of the year?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ "Cats Movie Trailer Unites the Internet Under One Shared Message: 'WTF Did I Just Watch?'". Adweek. 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (19 December 2019). "Critics find 'Cats' to be an 'Obscene,' 'Garish' and 'Overtly Sexual' Adaptation of the Hit Broadway Show". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers | Teaser Trailer | Disney+, archived from the original on 22 May 2022, retrieved 22 May 2022

- ^ Lawler, Kelly (17 August 2022). "Review: 'She-Hulk: Attorney at Law' is so close yet so far from greatness". USA Today. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Pulliam-Moore, Charles (17 August 2022). "SHE-HULK: ATTORNEY AT LAW IS PEAK UNCANNY VALLEY, BUT IT WORKS". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Howard, Kirsten (18 August 2022). "She-Hulk: Attorney at Law Episode 1 Review – A Normal Amount of Rage". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Somma, Ryan (15 October 2009). "Will James Cameron's Avatar Escape the Uncanny Valley?". Ideonexus.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

Terminator: Salvation took advantage of the spooky effect, intentionally or not, with a computer animated Arnold Schwarzenegger cameo.

- ^ Wadsworth, Kyle (7 December 2009). "Scaling the Uncanny Valley". Gameinformer.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

This would be a welcome counterpoint to the relatively poor rendering of a virtual Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator Salvation.

- ^ Mungenast, Eric (2 July 2015). "'Terminator Genisys' more than adequate". East Valley Tribune. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

One notable technological problem stems from the attempt to make old Schwarzenegger look young again with some digital manipulation — it definitely doesn't cross over the uncanny valley.

- ^ Holtreman, Vic (16 December 2010). "'TRON: Legacy' Review – Screen Rant". Screenrant.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (16 December 2010). "Following in Father's Parallel-Universe Footsteps". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Biancolli, Amy (16 December 2010). "TRON: Legacy". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (18 December 2016). "'Rogue One': That Familiar Face Isn't Familiar Enough". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

The Tarkin that appears in Rogue One is a mix of CGI and live-action, and it... doesn't work. — In fact, for a special effect that's still stuck in the depths of the uncanny valley, it's surprising just how much of the movie Tarkin appears in, quietly undermining every scene he's in by somehow seeming less real than the various inhuman aliens in the movie.

- ^ Lawler, Kelly (19 December 2016). "How the 'Rogue One' ending went wrong". USA Today. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

the Leia cameo is so jarring as to take the audience completely out of the film at its most emotional moment. Leia's appearance was meant to help the film end on a hopeful note [...] but instead it ends on a weird and unsettling one

- ^ Chang, Justin (10 October 2019). "Review: Two Will Smiths don't double the pleasure in the ill-conceived 'Gemini Man'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Trenholm, Richard (1 December 2019). "The Irishman: De-aging De Niro was a waste of money". CNET. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Miller, Matt (7 January 2020). "Some Deepfaker on YouTube Spent Seven Days Fixing the ###### De-Aging in The Irishman". Esquire. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ a b Muncy, Julie (8 September 2018). "This Video Uses the Power of Deepfakes to Re-Capture This Character's Cameo Appearance in Rogue One". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "OCCLUSION VFX - Tron DeepFake". 16 August 2019. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021 – via YouTube.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Bartneck, C., Kanda, T., Ishiguro, H., & Hagita, N. (2007). Is the uncanny valley an uncanny cliff? Proceedings of the 16th IEEE, RO-MAN 2007, Jeju, Korea, pp. 368–373. doi:10.1109/ROMAN.2007.4415111

- Burleigh, T. J. & Schoenherr (2015). A reappraisal of the uncanny valley: categorical perception or frequency-based sensitization? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1488. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01488.

- Burleigh, T. J., Schoenherr, J. R., & Lacroix, G. L. (2013). Does the uncanny valley exist? An empirical test of the relationship between eeriness and the human likeness of digitally created faces. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 759–771. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.021

- Chaminade, T., Hodgins, J. & Kawato, M. (2007). Anthropomorphism influences perception of computer-animated characters' actions. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(3), 206–216.Journal of Vision, 16(11):7, 1–25. doi:10.1167/16.11.7

- Cheetham, M., Suter, P., & Jancke, L. (2011). The human likeness dimension of the "uncanny valley hypothesis": Behavioral and functional MRI findings. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 126.

- Ferrey, A., Burleigh, T. J., & Fenske, M. (2015). Stimulus-category competition, inhibition and affective devaluation: A novel account of the Uncanny Valley. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 249. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00249

- Goetz, J., Kiesler, S., & Powers, A. (2003). Matching robot appearance and behavior to tasks to improve human-robot cooperation. Proceedings of the Twelfth IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication. Lisbon, Portugal.

- Ishiguro, H. (2005). Android science: Toward a new cross-disciplinary framework. CogSci-2005 Workshop: Toward Social Mechanisms of Android Science, 2005, pp. 1–6.

- Kageki, N. (2012). An uncanny mind (An interview with M. Mori). IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 19(2), 112–108. doi:10.1109/MRA.2012.2192819

- Kätsyri, J. & Förger, K. & Mäkäräinen, M. & Takala, T. (2015). A review of empirical evidence on different uncanny valley hypotheses: support for perceptual mismatch as one road to the valley of eeriness. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 390. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00390

- Misselhorn, C. (2009). Empathy with inanimate objects and the uncanny valley. Minds and Machines, 19(3), 345–359.

- Moore, R. K. (2012). A Bayesian explanation of the 'Uncanny Valley' effect and related psychological phenomena. Scientific Reports, 2, 864, doi:10.1038/srep00864.

- Mori, M. (1970/2012). The uncanny valley IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 19(2), 98–100. doi:10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811

- Mori, M. (2005). On the Uncanny Valley. Proceedings of the Humanoids-2005 workshop: Views of the Uncanny Valley. 5 December 2005, Tsukuba, Japan.

- Pollick, F. E. (forthcoming). In search of the uncanny valley. In Grammer, K. & Juette, A. (Eds.), Analog communication: Evolution, brain mechanisms, dynamics, simulation. The Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

- Ramey, C.H. (2005). The uncanny valley of similarities concerning abortion, baldness, heaps of sand, and humanlike robots. In Proceedings of the Views of the Uncanny Valley Workshop, IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots.

- Saygin, A.P., Chaminade, T., Ishiguro, H. (2010) The Perception of Humans and Robots: Uncanny Hills in Parietal Cortex. In S. Ohlsson & R. Catrambone (Eds.), Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 2716–2720). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

- Saygin, A.P., Chaminade, T., Ishiguro, H., Driver, J. & Frith, C. (2011). The thing that should not be: Predictive coding and the uncanny valley in perceiving human and humanoid robot actions. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(4), 413–422. doi:10.1093/scan/nsr025

- Schoenherr, J. R. & Burleigh, T. J. (2014). Uncanny sociocultural categories. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1456. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01456

- Seyama, J., & Nagayama, R. S. (2007). The uncanny valley: Effect of realism on the impression of artificial human faces. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 16(4), 337–351. doi:10.1162/pres.16.4.337

- Tinwell, A., Grimshaw, M., & Williams, A. (2010) Uncanny Behaviour in Survival Horror Games. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 2(1), pp. 3–25.

- Tinwell, A., Grimshaw, M., & Williams, A. (2011) The Uncanny Wall. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 4(3), pp. 326–341.

- Tinwell, A., Grimshaw, M., Abdel Nabi, D., & Williams, A. (2011) Facial expression of emotion and perception of the Uncanny Valley in virtual characters. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), pp. 741–749.

- Urgen, B. A. & Saygin, A. P. (2018). Uncanny valley as a window into predictive processing in the social brain. Neuropsychologia, 114, 181–185. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.04.027

- Vinayagamoorthy, V. Steed, A. & Slater, M. (2005). Building Characters: Lessons Drawn from Virtual Environments. Toward Social Mechanisms of Android Science: A CogSci 2005 Workshop. 25–26 July, Stresa, Italy, pp. 119–126.

- Yamada, Y., Kawabe, T., & Ihaya, K. (2013). Categorization difficulty is associated with negative evaluation in the "uncanny valley" phenomenon. Japanese Psychological Research, 55(1), 20–32.

- Zysk, W., Filkov, R., Feldmann, S. (2013). Bridging the Uncanny Valley - From 3D humanoid Characters to Virtual Tutors. The Second International Conference on E-Learning and E-Technologies in Education, ICEEE (2013), p. 54-59. ISBN 978-1-4673-5093-8, 2013 IEEE. doi:10.1109/ICeLeTE.2013.6644347

External links[edit]

- Miklósi, Ádám and Korondi, Péter and Matellán, Vicente and Gácsi, Márta. "Ethorobotics: A New Approach to Human-Robot Relationship". Frontiers in Psychology, 2017, 8, p. 958

- Your Brain on Androids UCSD news release about human brain and the uncanny valley.

- Almost too human and lifelike for comfort—research journal for an uncanny valley PhD project

- Relation between motion and appearance is communication between androids and humans

- The Uncanny valley Archived 19 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine - a visual explanation of the hypothesis with the application in gaming.

- Wired article: "Why is this man smiling?", June 2002.