Yakov Smirnoff

| Yakov Smirnoff | |

|---|---|

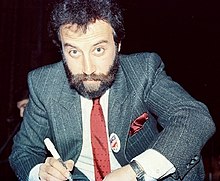

Smirnoff in a promotional image | |

| Birth name | Yakov Naumovich Pokhis |

| Native name | Яков Наумович Похис |

| Born | 24 January 1951 Odesa, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Medium |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1983–present |

| Genres |

|

| Subject(s) | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Notable works and roles |

|

| Website | yakov |

Yakov Naumovich Pokhis (Russian: Яков Наумович Похис; born 24 January 1951),[1] better known as Yakov Smirnoff (Russian: Яков Смирнов; /ˈsmɪərnɒf/), is an American comedian, actor and writer. He began his career as a stand-up comedian in the Soviet Union, then immigrated to the United States in 1977 in order to pursue an American show business career, not yet knowing any English.

He reached his biggest success in the mid-to-late 1980s, appearing in several films which include Moscow on the Hudson with Robin Williams, The Money Pit with Tom Hanks, Heartburn with Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep, and Brewster's Millions with Richard Pryor. He was a star of the television series What a Country! and was a recurring guest star on NBC's hit television series Night Court playing a part of Yakov Korolenko. His comic persona was of a naive immigrant from the Soviet Union who was perpetually confused and delighted by life in the United States. His humor combined a mockery of life under Communist states and of consumerism in the United States, as well as word play caused by misunderstanding of American phrases and culture, all punctuated by the catchphrase, "And I thought, 'What a country!'"

The Fall of Communism starting in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought an end to Smirnoff's widespread popularity, although he continued to perform. In 1993, he began performing year round at his own theater in Branson, Missouri. He occasionally still performs limited dates at his theater in Branson while touring worldwide. Smirnoff earned a master's degree in psychology from the University of Pennsylvania in 2006 and a doctorate in psychology and global leadership from Pepperdine University in 2019. He has also taught a course titled "The Business of Laughter" at Missouri State University and at Drury University.

Early life[edit]

The son of Naum Pokhis and Klara Pokhis, Smirnoff was born in Odesa, Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union (USSR). He was an art teacher in Odesa, as well as a comedian. As a comedian, he entertained occasionally on ships in the Black Sea, where he came into contact with Americans who described life in the United States to him. That was when he first considered leaving the country.[2]

After two years of attempting to leave, he came to the United States with his parents in 1977, arriving in New York City. His family was allowed to come to America because of "an agreement between the USSR and America to exchange wheat for Soviet citizens who wished to defect".[2] At the time, neither he nor his parents spoke any English.[2] On arrival to the United States, he was almost sent back to the USSR when his interpreter mistranslated his occupation, comedian, as "party organizer", which immigration authorities thought meant that he was an organizer for the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[3]

Smirnoff spent a portion of his early days in the United States working as a busboy and bartender at Grossingers Hotel in the Catskill Mountains of New York and living in the employee dormitory.[4]

Career[edit]

Smirnoff began doing stand-up comedy in the US in the late 1970s. He chose the last name "Smirnoff" after trying to think of a name that Americans would be familiar with; he had learned about Smirnoff vodka in his bartending days.[2]

In the early 1980s, he moved to Los Angeles to further pursue his stand-up comedy career. While there, he was roommates with two other aspiring comedians: Andrew Dice Clay and Thomas F. Wilson.[5] Smirnoff often appeared at renowned L.A. club the Comedy Store.

After achieving some level of fame, Smirnoff got his first break with a small role in the 1984 film Moscow on the Hudson; on the set, he helped star Robin Williams with his Russian dialogue.[2] He subsequently appeared in several other motion pictures, including Buckaroo Banzai (1984), Brewster's Millions (1985) and The Money Pit (1986). Among his numerous appearances on television, he was featured many times on the sitcom Night Court as "Yakov Korolenko", and appeared as a comedian and guest on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

He had a starring role in the 1986–87 television sitcom What a Country! In that show, he played a Russian cab driver studying for the U.S. citizenship test. In the late 1980s, Smirnoff was commissioned by ABC to provide educational bumper segments for Saturday morning cartoons Fun Facts, punctuated with a joke and Smirnoff's signature laugh.[6]

In 1987, Smirnoff was invited to a party hosted by Washington Times editor-in-chief Arnaud de Borchgrave which featured President Ronald Reagan as the guest of honor. Reagan and Smirnoff immediately hit it off due to Reagan's love of jokes about life in the Soviet Union. Reagan enjoyed telling such jokes in speeches, and Smirnoff became one of his sources for new material. An example of a joke Reagan later told that originated from Smirnoff was "In Russia, if you say, 'Take my wife - please', you come home and she is gone."[7] Smirnoff was enlisted by Dana Rohrabacher, who was then a speechwriter for Reagan, to help with material for Reagan's speeches, including a speech given in front of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev when Reagan visited the Soviet Union during the Moscow Summit in 1988. Rohrabacher later stated that Smirnoff became "one of the inner circle" of speechwriting advisers during Reagan's final years in office, due to the quality of Smirnoff's suggestions.[8]

In 1988, Smirnoff was the featured entertainer at the annual White House Correspondents' Dinner and he appeared in some commercials for hotel chain Best Western.

Since 1993, he has been performing at his own 2,000-seat[2] theater, and over the years has entertained more than five million people in a live setting. His 28th consecutive season was commemorated in Branson, Missouri in 2021. In the late 1990s he retooled his stand-up act to focus on the differences between men and women, and on solving problems within relationships.[2]

In 2002, Smirnoff appeared in episodes of King of the Hill ("The Bluegrass Is Always Greener") and The Simpsons ("The Old Man and the Key").

In 2003, he appeared on Broadway in a one-man show, As Long As We Both Shall Laugh, deemed by Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times as "warmhearted", "delightful" and "splendidly funny".[9] Smirnoff was also a featured writer for AARP Magazine and gave readers advice in his column, "Happily Ever Laughter".

After a successful career in television, movies and Broadway, Smirnoff received a master's degree in psychology from the University of Pennsylvania. He has taught classes at Drury University along with Missouri State University on this topic. He also gives seminars and self-help workshops on the topic of improving relationships.[2] Smirnoff earned his doctorate in psychology and global leadership at Pepperdine University, graduating in May 2019.

In 2016, Smirnoff produced and starred in a comedy special for PBS, Happily Ever Laughter,[10] which was named PBS Special of the Year.[citation needed]

Comedy style[edit]

"America: What a country!"[edit]

Some of Smirnoff's jokes involved word play based on a limited understanding of American idioms and culture:

- "I saw something that told me this was the place for me. It was a large billboard and it had my name on it: 'Smirnoff...America loves Smirnoff!'"[11]

- "One day the [bar] owner changed my hours and told me I'd be working the graveyard shift. I thought to myself, 'Wow, a bar in a cemetery. What a country! Talk about your last call!' During Happy Hour the place must be dead!"[12]

- "On my first shopping trip, I saw powdered milk...you just add water, and you get milk. Then I saw powdered orange juice...you just add water, and you get orange juice. And then I saw baby powder...I thought to myself, 'What a country!' I'm making my family tonight!"[13]

- "I was recently in a supermarket and I saw something called New Freedom. Freedom in a box! I said to myself, 'What a country!'"[14]

- At Denny's: "When I went in to be seated, the hostess asked me, 'How many in your party?' I said, 'Two million.' She gave me a corner booth."[15]

- While holding a hot dog: "In Russia, we don't eat this part of the dog."[16]

Other jokes involved comparisons between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.:

- "Thanksgiving is my favorite American holiday. I really like parades without missiles. (I'll take Bullwinkle over a tank any day!)"[17]

- "I only make fun of Cleveland because all Americans do. Every country has one city that everybody makes fun of. For example, in Russia we used to make fun of Cleveland."[18]

- "They don't play baseball in the Soviet Union because there, no one is safe."[19]

- "There aren't any such things as credit cards in the Soviet Union, not even American Express. They do, however, have Russian Express—'Don't leave home!'"[20]

- "America has many wonderful things we never had in Russia...like warning shots."[21]

Russian reversal[edit]

Smirnoff is often credited with inventing or popularizing the type of joke known as the "Russian reversal", in which life "in Soviet Russia" or "in Russia" is described through an unexpected flip of a sentence's subject and object.[22] One example occurs in a 1985 Miller Lite commercial, in which Smirnoff states, "In America, there is plenty of light beer and you can always find a party. In Russia, party always finds you."[23] Another can be found in his 1987 book America on Six Rubles a Day: "Show business in America is different from what I was used to. Here you have to find an agent. In Russia, the agent always finds you."[18] Despite Smirnoff rarely using the joke format himself, he has often been directly associated with it throughout pop culture, including in episodes of both Family Guy[24] and The Simpsons.[22]

Time magazine observed that the earliest example of the joke can be found in Cole Porter's 1938 musical Leave It to Me! and furthermore credited Bob Hope for first introducing the format to a wide audience while hosting the 30th Academy Awards in 1958.[22]

Painting[edit]

Smirnoff is also a painter and has frequently featured the Statue of Liberty in his art since receiving his U.S. citizenship. On the night of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, he started a painting inspired by his feelings about the event, based on an image of the Statue of Liberty. Just prior to the first anniversary of the attacks, he paid US$100,000 for his painting to be transformed into a large mural. Its dimensions were 200 feet by 135 feet (61 m by 41 m). The mural, titled "America's Heart,"[25] is a pointillist-style piece, with one brush-stroke for each victim of the attacks. Sixty volunteers from the Sheet Metal Workers Union erected the mural on a damaged skyscraper overlooking the ruins of the World Trade Center. The mural remained there until November 2003, when it was removed because of storm damage.[26] Various pieces of the mural can now be seen on display at his theater in Branson, Missouri.

The only stipulation he put on the hanging of the mural was that his name not be listed as the painter.[27] He signed it: "The human spirit is not measured by the size of the act, but by the size of the heart."[28]

Personal life[edit]

Smirnoff became an American citizen on 4 July 1986.[29]

Smirnoff had a wife, Linda; they divorced in 2001.[30][31] They have two children: a daughter, Natasha, born in 1990, and a son, Alexander, born in 1992.[29]

He remarried in 2019 to Olivia Kosarieva.

Filmography[edit]

Among his film credits, Smirnoff has co-starred in movies with Robin Williams (Moscow on the Hudson, 1984), Tom Hanks (The Money Pit, 1986), and Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep (Heartburn, 1986), in addition to single episodes of several TV series.[32]

- Moscow on the Hudson (1984) as Lev

- The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984) as National Security Advisor

- Brewster's Millions (1985) as Vladimir

- The Money Pit (1986) as Shatov

- Heartburn (1986) as Contractor Laszlo

- What a Country! (1986–1987, TV Series) as Nikolai Rostapovich

- Up Your Alley (1989) as Russian Man

- Night Court (1984-1990, TV Series) as Yakov Korolenko; appeared in five episodes

References[edit]

- ^ Rose, Mike (24 January 2023). "Today's famous birthdays list for January 24, 2023 includes celebrities Neil Diamond, Aaron Neville". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Yakov Smirnoff interview". The Comedy Couch. 5 February 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007.

- ^ Buck, Jerry (9 December 1987). "Comedian has last laugh". Observer-Reporter (AP TV Writer). Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

He was nearly sent back to the Soviet Union on the next plane after the interpreter, groping for the right translation of comedian, came up with 'party organizer.' For a moment, the immigration people thought he was an organizer for the Communist Party.

- ^ "Didja hear the one about the comedian who defected?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "What's What With ... Tom Wilson". Philadelphia. 3 December 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Yakov Smirnoff official biography". Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (21 August 1987). "WASHINGTON TALK; Reagan and the Russians: The Joke's on Them". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ Ufberg, Ross (23 March 2017). "Yakov Smirnoff Brings Reagan-Era Optimism to the Age of Trump". Tablet. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "THEATER IN REVIEW; Land of the Free? What a Country!". The New York Times. 16 April 2003. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Yakov Smirnoff's Happily Ever Laughter". PBS. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 5–6.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 52.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 55.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 40.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 36.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 123.

- ^ a b Smirnoff 1987, p. 120.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 108.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Smirnoff 1987, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Rothman, Lily (22 February 2015). "In Soviet Russia, the Oscars Host You". Time. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ "Yakov Smirnoff Miller Lite Commercial (1985)". YouTube. 11 November 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ "In Soviet Russia, Yakov Smirnoff's TV commercials watch you". The A.V. Club. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "The mural in Yakov Smirnoff's official website". Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Frangos, Alex (3 December 2003). "Trade Center Mural Is Retired". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ Farrow, Connie (27 December 2002). "Branson comedian Smirnoff's mural now hangs at NY's Ground Zero". seMissourian.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Yakov's Mural at Ground Zero". www.yakov.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ a b Nollen, Diana (14 March 2013). "Yakov Smirnoff spreading joy of living 'happily ever laughter'". Hoopla. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013.

- ^ Cordova, Randy (19 August 2016). "Yakov Smirnoff talks psychology of love, laughter on new PBS special". azcentral. The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

Comedian Yakov Smirnoff and his wife ended their marriage in 2001.

- ^ Mullins, Luke (5 September 2017). "Who Can Save Us From Russia? Yakov Smirnoff Is Still Available". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

After a divorce in 2001, he became fixated on the role of laughter in male/female relationships.

- ^ "YAKOV". Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Smirnoff, Yakov (1987). America on Six Rubles a Day. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-75523-5.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Yakov Smirnoff at IMDb

- "Yakov Smirnoff". Branson Tourism Center. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- Simon, Scott (12 April 2003). "Yakov Smirnoff, Laughing All the Way to Broadway". Weekend Edition Saturday. Retrieved 12 June 2016. Interview.

- 1951 births

- Drury University faculty

- Internet memes

- Jewish American comedians

- Jewish male comedians

- Living people

- People from Branson, Missouri

- Entertainers from Odesa

- Soviet emigrants to the United States

- University of Pennsylvania alumni

- People with acquired American citizenship

- Comedians from Missouri

- 20th-century American comedians

- 21st-century American comedians

- Jewish Ukrainian comedians

- Odesa Jews

- 21st-century American Jews

- American male comedians